CHAPTER 148 Skull Tumors

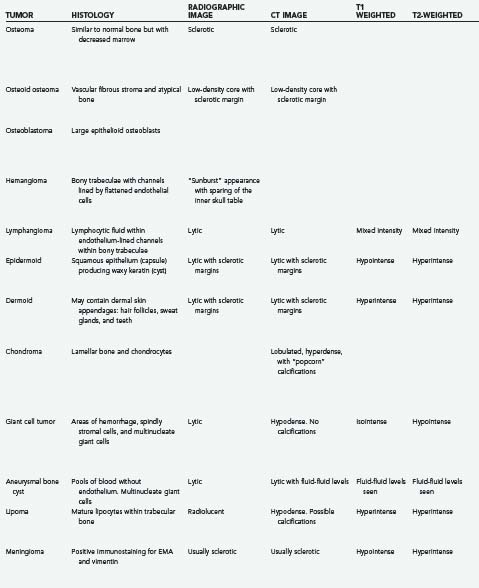

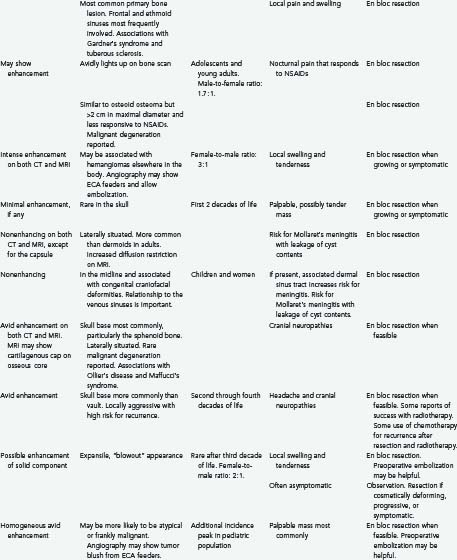

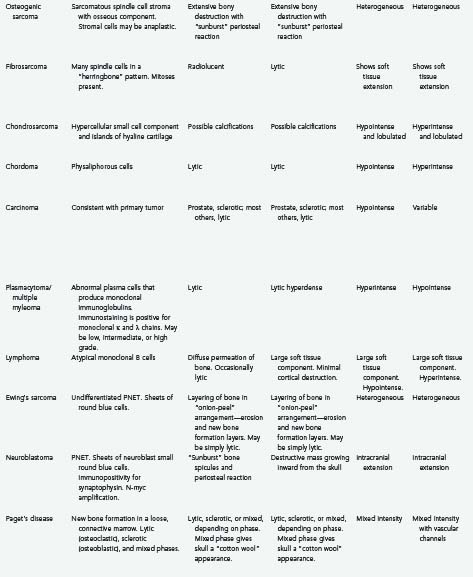

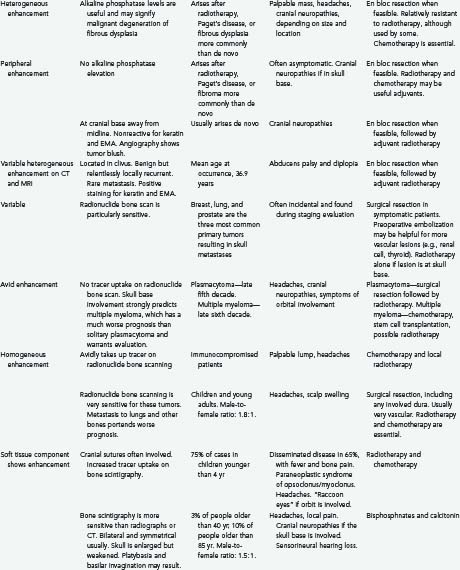

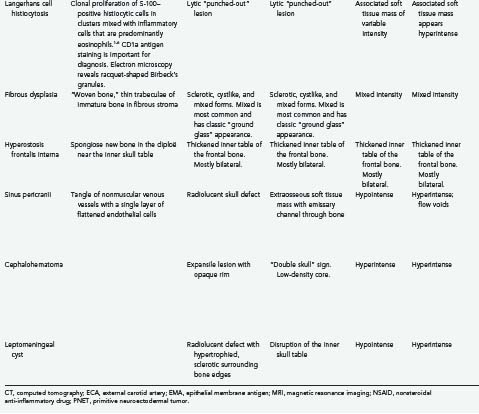

Tumors of the skull make up a small but significant portion of neurosurgical practice. These lesions may be primary neoplastic, secondary neoplastic, or non-neoplastic. Their characteristics and treatments are summarized in Table 148-1.1–6

Primary Skull Neoplasms

Benign

Osteoma/Osteoid Osteoma/Osteoblastoma

Osteomas are the most common primary skull lesions.7 These benign, slow-growing tumors have a predilection for the craniofacial bones and paranasal sinuses and consist of abnormally dense but otherwise normal bone.7–11 Osteomas of the calvaria typically arise from the external table of the skull but may also arise from the inner table.11 Their most common location is the frontal sinus, followed by the ethmoid sinus, which together account for 75% of cases.8,11 Osteomas of the maxillary sinus and sphenoid sinus have been reported as well.8,11 These lesions are often asymptomatic but may cause local swelling and tenderness, facial pain, rhinorrhea, and sinusitis.8,12 Additionally, osteomas tend to expand bone, which may lead to displacement of the frontal lobes and orbital contents.10 Subsequent erosion of the dura and arachnoid may cause cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) rhinorrhea with resultant meningitis or brain abscess.10 If sinus mucosa herniates through the eroded bone into the intracranial space, a mucocele may develop.10 En bloc surgical resection of osteomas is often curative and is indicated even for asymptomatic lesions if they grow rapidly or involve the orbit.7

Histologically, osteomas generally consist of mature bone similar to normal bone, albeit with decreased marrow.9 There are three histopathologic types of osteoma: compact, cancellous, and fibrous. The compact (or “ivory”) type tends to occur over the outer table of the skull, whereas the cancellous and fibrous types tend to involve the inner table or, rarely, the diploë.2

Osteomas produce osteoblastic changes that may appear as zones of hyperostosis on radiography or computed tomography (CT).8,11 They typically appear as a smoothly homogeneous, sharply demarcated sclerotic mass extending outward from the bone without exerting any mass effect on adjacent soft tissue.8,11

Multiple osteomas may be associated with Gardner’s syndrome—an autosomal dominant disease characterized by the triad of osteomatosis, colonic polyposis, and soft tissue tumors.11,13 The lesions may affect the skull proper, as well as the mandible, facial bones, and paranasal sinuses.13 Osteomas have also been reported in association with tuberous sclerosis.8,11 Evaluation of patients with paranasal osteomas should thus include colonoscopy and DNA testing.12

Initially described by Jaffe in 1953 and first noted in the skull by Prabhakar and associates in 1972, osteoid osteomas are bone-forming neoplasms characterized by the production of osteoid or mature bone by tumor cells.8,9,14 These tumors are associated with swelling and local tenderness, particularly at night, which respond dramatically to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).8,14–17 This pain is often quite severe relative to the small size of the lesion.15 Osteoid osteoma is more common in adolescents and young adults and is relatively uncommon after 30 years of age.16,17 There is a distinct male predilection (1.7 : 1).16,17 The lesion typically develops slowly and may actually cause symptoms before being discernible on plain radiographs.16

Histologically, osteoid osteoma is characterized by trabeculae of atypical bone within a highly vascular fibrous stroma.1,14,16

Radiologically, this lesion is manifested on plain radiographs and CT by a low-density central nidus surrounded by a high-density sclerotic margin.1,14,15,18 Nuclear medicine bone scanning may be helpful in equivocal cases because the nidus of an osteoid osteoma lesion avidly “lights up” with tracer (less at the sclerotic margin).9 More recently, at least one report has suggested that magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with gadolinium contrast enhancement demonstrates nidus conspicuity equal or superior to that seen with thin-section CT.19

With symptomatic or cosmetically deforming lesions, en bloc resection appears to be the treatment favored from an oncologic standpoint, although the risk of recurrence after simple curettage is low.15 Spontaneous regression of osteoid osteoblastomas has been reported.17

Histologically, osteoblastomas are closely related to osteoid osteomas and have been referred to as giant osteoid osteomas.9 Osteoblastomas share many of the same histologic features as osteoid osteomas, but they are greater than 2 cm in maximal diameter and are less responsive to NSAIDs for pain relief.20 Some histologic distinctions may include increased vascularity and a less organized pattern of osteoid and reticular bone in osteoblastomas.9 Some believe that although osteoid osteomas tend toward spontaneous regression,17 osteoblastomas may rarely undergo malignant transformation to osteosarcoma.9,20 These more aggressive osteoblastomas may be characterized histologically by “epithelioid” osteoblasts that are twice the size of normal osteoblasts.9 As with osteoid osteoma, en bloc surgical excision of osteoblastomas usually results in pain relief, and recurrence is rare.20 Treatment by partial resection or curettage is associated with a 10% tumor recurrence rate.15

Hemangioma/Lymphangioma

Although hemangiomas of bone are not uncommon, calvarial hemangiomas are relatively rare.21,22 These cranial vascular lesions are found more commonly in women than men (3 : 1 ratio)11,21–24 and have a predilection for the frontal and parietal areas.11,21,23,25 Hemangiomas vary in size from microscopic to massive and may be classified as either capillary or cavernous, depending on their histologic appearance.26 In 15% of cases, the lesions are multiple.21,24 Skull hemangiomas are often small and asymptomatic but may evolve into a visible and palpable area of tenderness and swelling.22,23 The scalp overlying the lesion is typically freely mobile.22 Hemangiomas in less common locations such as the base of the skull or orbit may cause cranial neuropathies or proptosis.21,25

Histologically, cavernous hemangiomas are unencapsulated sinusoidal channels lined by flattened endothelial cells within bony trabeculae. Capillary hemangiomas are similar but contain more capillary-sized vessel loops; frequently, a mixture of both histologic forms is present. The bony trabeculae are thought to be caused by osteoclastic remodeling in response to stress from the enlarging vascular malformation.1,21,25

Hemangiomas are always benign and may remain static for long periods.21,23,25 When they do grow, one of two growth patterns is typically exhibited: a “sessile” pattern involving extension along the diploë or a “globular” pattern with expansion of the skull and eventual extension into the surrounding soft tissues.5 The sessile type is more common.11 Association of skull hemangiomas with hemangiomas elsewhere in the body (including other bones), such as in the liver, kidney, spleen, and adrenal gland, has been reported, although true metastases have not.21

Calvarial hemangiomas tend to involve the outer table of the skull and the diploë, with relative sparing of the inner table of the skull.11,22 The classic appearance of a hemangioma on radiographs is a “sunburst” or “honeycomb” pattern.11,21,25 There is generally no surrounding sclerosis, and in fact, there may be a halo of decalcification.21,25 This pattern can perhaps best be appreciated on CT bone windows.24,25 Enhancement with contrast material is intense on both CT and MRI. Angiography may demonstrate feeding of the hemangioma by branches of the external carotid artery (ECA) and often by the superficial temporal artery or the middle meningeal artery,11,21,24 and it may suggest a pathway for preoperative embolization.22,25 Radionuclide bone scanning is of little use in the assessment of these lesions.5

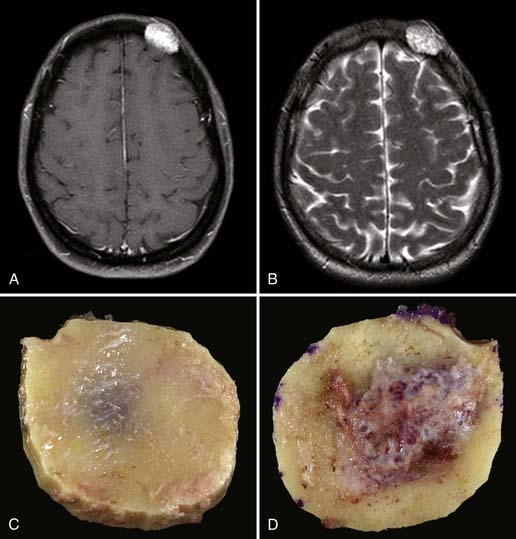

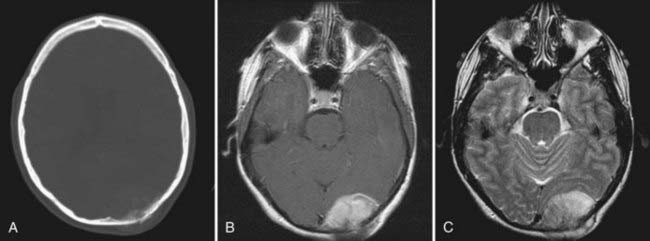

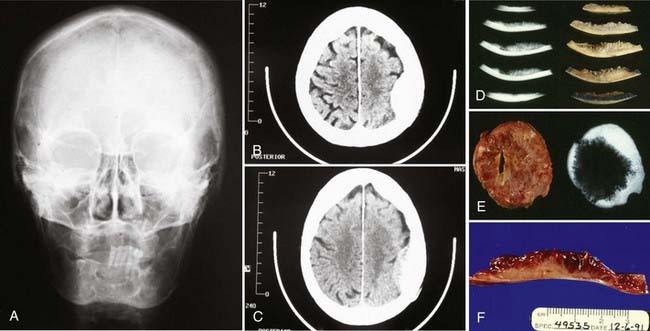

En bloc surgical excision with establishment of normal bony margins (Fig. 148-1), when indicated, typically results in cure.21,23,25 Simple curettage may increase the chance of leaving residual disease and tumor recurrence.22 Some have advocated radiation treatment for residual tumor or for skull base lesions that are difficult to access surgically.20 Treatment of a symptomatic cavernous hemangioma of the occipital condyle with methacrylate embolization has also been reported.27

Lymphangioma is a congenital soft tissue tumor most commonly found in the neck; osseous involvement is rare.1,28,29 The first lymphangioma of bone was reported in 1947; the first solitary calvarial lesion without other visceral or skeletal involvement was noted in 1974.28,30 Skull base involvement is even more uncommon and has been reported to cause CSF rhinorrhea and cranial neuropathy.28,31 Lymphangioma is more common in the first 2 decades of life and is found with equal frequency in men and women.28,29,32 The most common finding is a palpable, possibly painful mass. Spontaneous bleeding into the mass has been described.29,32 One report described two particularly severe pediatric cases of lymphangiomatosis leading to massive osteolysis of the skull.33

Histologically, this benign lesion is very similar to hemangioma.28,30 Typically, the tumor is composed of large spaces lined with endothelium and filled with proteinaceous lymphocytic fluid within a fibrous connective tissue stroma. Bony trabeculae may also be present.1,29 The proportion of lymphocytic fluid to fibrous stroma may vary considerably.32 There are three histologic subtypes: cystic (cystic hygroma), capillary, and cavernous.28,29

As seen on plain radiographs, the lesions are lytic with a well-demarcated, nonsclerotic margin.29,30 Multiple lesions are not uncommon.29 The variable histologic makeup of lymphangioma causes the CT appearance to be similarly variable,32 and with the administration of contrast material, enhancement is weak if present at all.32 Lymphangiomas have a characteristic mixed-intensity, “bubbly” appearance on MRI sequences.32 Radionuclide bone scanning may be a useful diagnostic adjunct for these lesions.30 En bloc surgical resection is the treatment of choice for symptomatic or progressive lesions.28,29

Embryonic: Epidermoid and Dermoid

Epidermoid cysts and dermoid cysts together represent the epithelial inclusion cysts or “pearly tumors.”34,35 Both are thought to be formed in the third to fifth week in utero as a result of faulty separation of the ectoderm and neuroectoderm.36,37 Epidermoids are somewhat more common, are usually laterally situated, and are often found in adults.35,38 Dermoids are more commonly found in the midline and may be associated with congenital malformations.35,38–40

The first diploic epidermoid was described by Cushing in 1922. These cysts are usually congenital lesions caused by ectodermal rests within the skull diploë.38,40–43 Epidermoids have also been reported to be caused by traumatic induction of epidermal rests.40,44 Epidermoids are benign, slow-growing lesions, but they can undergo malignant change.40,45 They are typically asymptomatic, and a palpable painless lump is frequently the first sign.11,38,40,42 Giant intradiploic cysts can, however, cause elevated intracranial pressure and headaches.38,44,46 Rarely, intracranial extension occurs and results in seizures or venous sinus obstruction.11,38,40,42,47 Intracranial rupture plus hemorrhage of diploic epidermoids has also been reported after head trauma.40

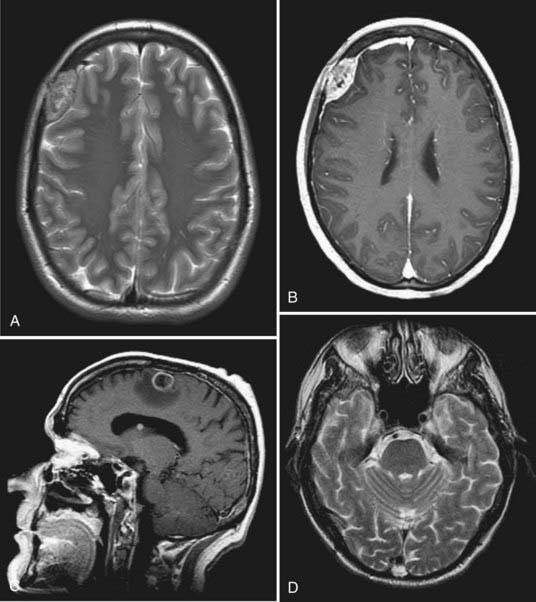

Epidermoid cysts are usually well circumscribed, with a smooth, irregularly nodular capsule (Fig. 148-2).35 The lining of epidermoids is keratin-producing squamous epithelium.34,48 The cyst contains soft, white, waxy, grumous flaky keratin; leakage of the cyst contents into CSF may produce a severe chemical meningeal response known as Mollaret’s meningitis.34,35 Progressive exfoliation of the cyst wall toward the interior of the cyst causes a linear growth rate and gives its contents a lamellar appearance.11,35,38,48 The linear growth rate of the cyst is more similar to that of normal skin than to the exponential growth of most neoplasms.35

The radiographic appearance of epidermoids is that of a lytic lesion with sclerotic margins and diploic expansion.11,38,42,43,48 CT and MRI generally demonstrate a nonenhancing lesion with imaging characteristics similar to CSF, although they may be of mixed intensity on all imaging sequences and the capsule may show enhancement. Cholesterol within the cyst may give it a hypodense appearance on CT.11,38,43 CT is particularly useful for assessment of diploic expansion and for detecting destruction of the inner and outer skull tables, as well as any intracranial extension.38,41,44,48

Dermoid cysts are similar to epidermoids, although they are typically found in the midline, are more common in children and women, and may be associated with congenital malformations.35,38,39 They commonly occur at the anterior fontanelle and occipital squama.35,36,39,49,50

Dermoids grow by both desquamation and glandular secretion.51 As a result, the cyst typically contains thick foul-smelling yellow material in which hair may be entangled.35 Unlike epidermoids, the lining of dermoids contains dermal skin appendages: hair follicles, sweat glands, and, rarely, teeth.34,48

Similar to epidermoids, dermoids are often asymptomatic; their progressive outward expansion may lead to a palpable mass, and inward growth may compress the brain.39

Dermoids have CT and MRI characteristics similar to those of fat; they generally do not show contrast enhancement with either modality.51 Plain radiographs demonstrate an osteolytic region occasionally surrounded by a sclerotic border.49 CT shows a round, well-demarcated, hypodense lesion.51

Intracranial extension and involvement of the venous sinuses may be significant, and a preoperative magnetic resonance venogram is essential for determining this relationship.36,49,50 Dermoid tumors in the occipital region may also be associated with a dermal sinus tract and a consequent risk for meningitis or intracranial abscess.36,50

The treatment of choice for both types of inclusion tumor is complete surgical resection, which results in cure.38,40,42,44 A margin of normal bone is often resected to avoid disrupting the cyst capsule.41 Ideally, the tumor should be dissected away from the dura, although in some cases the dura must be resected as well.41 The risks related to incomplete surgical resection include recurrence, progression to squamous cell carcinoma, infection, and aseptic meningitis.35,36,39,41,44,45,52 The prognosis in patients whose tumors undergo malignant transformation is poor.41,44

Chondroma (Osteochondroma)

Chondromas (osteochondromas) are slow-growing benign tumors of cartilage. They are the most common benign skeletal lesion and are thought to arise from ectopic hyaline cartilaginous rests trapped within suture lines.1,53–57 In the skull, these lesions are so rare that Cushing found only 3 in his series of 2033 cases.58 Chondromas are well-demarcated tumors that are generally manifested as a smooth round mucosa-covered mass.1,58,59 Chondromas are most commonly found at the skull base (usually anterior to the pons), particularly in the sphenoid bone, or bordering the foramen lacerum,10,26,34,57,59,60 although convexity chondromas have been reported.10,57,60 Symptoms typically develop slowly and may include decreased visual acuity, ophthalmoplegia, tinnitus, dizziness, headaches, or facial pain.58,59 They may occasionally be associated with other chondromas in the skeleton, as in Ollier’s disease, or with multiple hemangiomas (Maffucci’s syndrome).56,60

Histologically, chondromas are composed of normal-appearing chondrocytes without pleomorphism or mitotic activity. Dense spicules of lamellar bone interspersed with marrow and fat cells are capped by cartilage of varying thickness.1,11,53,54,59 Generally, these tumors are confined by a capsule and do not invade the brain.10 Rare malignant degeneration of chondroma to chondrosarcoma has been documented.26,58

On CT, osteochondromas appear as well-demarcated, off-midline, lobulated, contrast-enhancing, dense masses contiguous with the underlying bone and marked by “popcorn” calcifications.53,54,59 Chondromas show avid contrast enhancement on MRI as well.59 Additionally, MRI is helpful for appreciating the thin cartilaginous cap overlying the dense osseous core.53,54 CT helps determine the extent of bone erosion.59

Complete resection, including the cartilaginous capsule, is the treatment of choice and is believed to be curative, although it is often difficult to achieve.54,56,59,60

Giant Cell Tumor

Giant cell tumors of bone are benign, locally aggressive lesions characterized by well-vascularized tissue infiltrated with multinucleate giant cells.39,61–66 Less than 2% of these lesions are found in the skull10,39,61,62; when present, they typically originate from the skull base, particularly the sphenoid or temporal bone.10,61,62,66 They usually appear in the second through fourth decades of life and cause destruction of the sphenoid bone and sella turcica.10,39,62,63 Initial symptoms may include headache, trigeminal paresthesias, ophthalmoparesis, visual loss, endocrinopathy, and changes in mental status.62,66 Lesions in the temporal bones may cause conductive hearing loss or facial weakness.61,62,66,67 Some giant cell tumors may arise in the skull secondary to Paget’s disease.39,64,68

Grossly, giant cell tumors are composed of cystic and hemorrhagic areas. Histologically, they are characterized by areas of hemorrhage, many spindly stromal cells, and numerous multinucleate giant cells.61,63,64 Molecular genetic analysis of laser microdissections suggest that the stromal cells are the true neoplastic component. The giant cells are a secondary inflammatory response rather than the primary element that the name implies. The extensive hemorrhagic areas may make it difficult to differentiate this lesion from an aneurysmal bone cyst.64,66 Giant cell tumors have a low risk for metastasis but are often locally aggressive, with a high risk for recurrence.62,64,67 However, there is little correlation between any of the histologic features of this lesion and its biologic behavior.66,67 A malignant variant of this tumor (osteoclastoma) was reported in one patient with Paget’s disease.10 Rare cases of intradural and intraparenchymal invasion have also been reported.61,66

Radiologically, these tumors are well-demarcated, lytic lesions without a sclerotic border or periosteal reaction.61,62,64,65 CT typically shows a homogeneously hypodense mass with avid enhancement and no calcifications.61,65 On MRI, the mass appears isointense on T1-weighted sequences and hypointense on both T2- and diffusion-weighted images.62,65 The presence of hemosiderin probably accounts for the hypointensity on T2 images.65

Gross total resection of giant cell tumors is ideal but not always feasible.61,62,66 The recurrence rate and prognosis associated with these lesions both correlate with the extent of resection.39,62,66 Simple curettage has been reported to have a tumor recurrence rate as high as 70%, whereas gross total resection has a recurrence rate of just 7%.63,64 En bloc removal with margins is best, but its feasibility is often limited by anatomic constraints. The choice of reoperation or radiotherapy for partially resected giant cell tumors is a matter of controversy61,66 in that there is the risk for malignant transformation if residual tumor is present and a risk for induction of sarcoma with irradiation.61,66 Good results with radiation treatment after tumor recurrence have been reported.66,67,69 Additionally, some authors have reported the use of chemotherapy for recurrent or metastatic tumors, or both, although this protocol remains controversial.62,67 The sarcoma regimen of methotrexate, doxorubicin (Adriamycin), and cyclophosphamide is most commonly used but is generally reserved for particularly aggressive tumors that have recurred despite multiple resections and radiation treatments.67

Aneurysmal Bone Cyst

Aneurysmal bone cysts are benign, non-neoplastic, expansile lesions of unknown cause that can occur anywhere in the body, including the skull in rare cases.1,39,70–72 Approximately 30% of cases are associated with antecedent trauma or with other lesions such as fibrous dysplasia and osteoblastoma. Recognition of aneurysmal bone cysts as a distinct clinical entity was thus initially met with some resistance.1,70,73–76 Lichtenstein hypothesized that the cysts are only secondarily associated with trauma and are more likely to be caused by a circulatory disturbance resulting in venous hypertension and venous pooling within the bone.74 These solitary, expansile, erosive lesions are more commonly found in young persons and are rare after the third decade of life.11,39,70,73,75 There is a 2 : 1 female-to-male preponderance.71,73 Aneurysmal bone cysts cause symptoms by local compression or cosmetic deformity71,75; a typical finding is local swelling and tenderness of a few months’ duration.39,73,75 Lesions at the skull base may cause ptosis, exophthalmos, visual loss, hearing loss, and facial weakness.71,75

Grossly, aneurysmal bone cysts are distinguished by vascular channels that give them a sponge-like appearance and account for brisk hemorrhage during surgical resection. Soft tissue and bone spurs may septate the mass, but the overall appearance is osteolytic.39,71 Histologic examination reveals communicating pools of venous blood without endothelium in a thin matrix of fibro-osseous strands along with frequent multinucleate giant cells. The appearance may often be similar to that of giant cell tumors, and distinguishing between the two entities can be difficult.1,39,64,66,70,71,73,75

On imaging studies, the finding of a lytic, loculated lesion with fluid-fluid levels caused by layering of blood products within internal cavities is highly suggestive of an aneurysmal bone cyst. MRI is superior to CT in visualizing these fluid-fluid levels.11,70,71,73,75 The lesion typically begins in the diploë, and expansion or “blowout” of the inner and outer cortices may be appreciated on plain radiographs or CT.70,71,73,75 Blowout of the inner skull table confirms the typical intracranial involvement of these lesions.71 The solid portion of the lesion may show contrast enhancement.70,71,76

The treatment of choice for aneurysmal bone cysts is gross total resection, which is curative when feasible.39,70,71,73,75 Preoperative embolization has been reported to be a helpful presurgical adjunct.70 The most important factor affecting tumor recurrence is the extent of resection; partial resection or curettage has been associated with recurrence rates as high as 71%.39,70,71,75 Other factors influencing recurrence include the age of the patient, the size of the lesion, and the presence of mitosis in the lesion.71 Because these lesions are benign and non-neoplastic, radiotherapy and chemotherapy are not indicated.70,71 Radiotherapy was used in the past but has fallen out of favor because of the risk of inducing sarcomatous change.71 Chartrand-Lefebvre and coauthors reported good results with sclerotherapy for a greater sphenoid wing lesion in one patient.77 Rare spontaneous regression of aneurysmal bone cysts of the skull has been reported.72

Lipoma

Intraosseous lipomas are rare lesions that represent 0.08% of all bone tumors; fewer than 20 cases have been reported in the world literature.78–84 They are generally benign, solitary, well-circumscribed, mobile, slow-growing, asymptomatic masses.1,81,83,84 The cause of lipomas arising in the skull is controversial.82 Some believe that the potential for intraosseous lipomas resides in the presence of fat cells in all skeletal bone marrow.35,81,83 Alternatively, intraosseous lipomas could arise from maldifferentiation of mesenchymal stem cells covering the maturing brain.83 Some have characterized intraosseous lipomas as hamartomas rather than true tumors.78

Histologically, skull lipomas consist of a proliferation of mature lipocytes within normal trabecular bone. A fibrous capsule may be present.78,80,83 At low magnification, lipomas resemble normal adipose tissue with lobulation.26,83

Radiologically, the lesions have the imaging characteristics of normal lipomatous tissue on CT and MRI, and this may obviate the need for biopsy.81,83 On plain radiographs, a well-demarcated, radiolucent lesion is noted, with occasional expansion of the diploë.81,82 CT demonstrates a hypodense expansile mass in the diploë separating the inner and outer tables, with or without periosteal reaction. Calcifications may be interspersed.78,80,81,83,84 Lipomas typically appear hyperintense on T1 sequences and isointense to hyperintense on T2 and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequences.78,85

Skull lipomas are generally asymptomatic incidental findings that do not require treatment.78,81 One case has been reported of sphenoid bone involvement by an intraosseous lipoma with intrasellar and suprasellar extension that caused visual disturbance and hypopituitarism.86 In asymptomatic patients, observation with serial imaging studies is the standard of treatment78,81 because the risk for malignant degeneration is thought to be very low.81 Resection may be carried out for correction of cosmetic deformity or for compression-related symptoms.80,82,84,86 The recurrence rate after resection of these benign slow-growing tumors is as yet unknown.83

Meningioma

Intraosseous (intradiploic) meningiomas are uncommon. True primary intraosseous meningiomas do not involve the inner or outer tables of the skull or the dura.87 As meningiomas with no dural attachment, these tumors may be categorized as “ectopic meningiomas” or “primary extradural meningiomas.”87,88 These are rare lesions that account for less than 2% of all meningiomas.88 Intraosseous meningiomas constitute 14% of primary extradural meningiomas.89

Several differences between primary extradural meningiomas and their more common intradural counterparts have been observed. The female preponderance of diploic meningiomas may not be as pronounced as it is with other meningiomas, although this finding is somewhat inconsistent.87,88 Second, although both intradural and ectopic meningiomas affect adults, only ectopic meningiomas have a second incidence peak in the pediatric population.88,90 Finally, extradural meningiomas may have a greater likelihood of being atypical or frankly malignant than intradural meningiomas do (11% rather than 2%).88,91

Intradiploic meningiomas are thought to arise from rests of arachnoid cap cells trapped within sutures at birth and during molding of the head.92,93 An alternative hypothesis is that ectopic meningiomas arise from abnormal differentiation of multipotent mesenchymal cells.87,88 Their cause may in fact be multifactorial.88 Awareness of a painless, slowly growing, palpable mass is the most common manifestation.87,88,90,94 Headaches and local tenderness are also possible.87,93 Lesions in the temporal bone may cause hearing loss or facial weakness.95,96 A case of multiple intraosseous meningiomas has been reported.97

Histologically, intraosseous meningiomas are not different from their intradural counterparts; they have a wide range of histopathologic findings and positive immunostaining for epithelial membrane antigen and vimentin.88,89,94

On plain radiography and CT, most intraosseous meningiomas are hyperostotic, although some are lytic or both lytic and sclerotic.87,89,90,92,95 There is some speculation that as the lesion progresses, it becomes more lytic and less sclerotic.92 CT is often the most helpful imaging modality because it allows assessment of the extent of bone involvement.87,89,94,96,98 CT and plain radiographs demonstrate expansion of the diploë, with the inner and outer tables of the skull separated and thinned over the biconvex mass.89,91,93 As seen with MRI, the tumors appear hypointense on T1-weighted and hyperintense on T2-weighted images.91 As with intradural meningiomas, intraosseous meningiomas display homogeneous contrast enhancement on both CT and MRI.89,91,98 On basal views of the skull, the foramen spinosum may be enlarged because of hypertrophy of the middle meningeal artery.92 Using angiography, the intradural arteries and dural sinuses are seen to be pushed away from the inner table of the skull; this is the opposite of what is found with intradural meningiomas, wherein the vessels are displaced toward the inner table.92 There may be a tumor blush from its branch feeders from the ECA.98

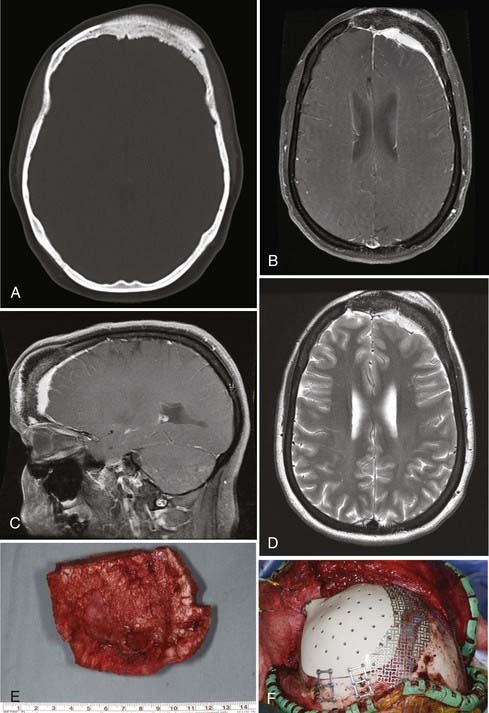

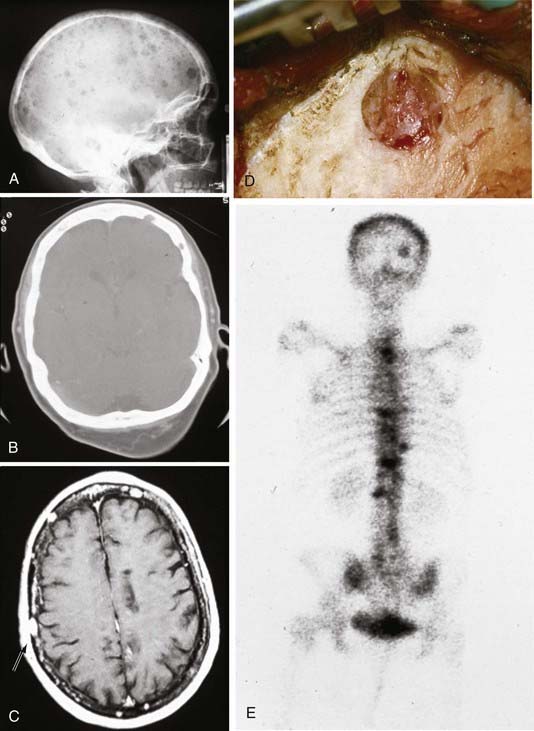

Intraosseous meningiomas of the skull are seldom correctly diagnosed preoperatively.87,88 Surgical resection is the treatment of choice for these lesions (Fig. 148-3). En bloc resection with margins, when feasible, may decrease the risk for recurrence.87,88,90,91,93,94,96

Malignant

Osteogenic Sarcoma

Osteogenic sarcoma (osteosarcoma) is the most common malignant tumor of bone, although it is relatively rare in the skull.99–103 In the skull, the cranial vault is involved more frequently than the base.102 These tumors may arise de novo or, more commonly, as a sequela of radiation treatment or another bone disorder such as Paget’s disease or fibrous dysplasia.1,10,100,101,103–106 Osteogenic sarcomas that develop secondary to radiation treatment are thought to be more aggressive and have a worse prognosis than those arising de novo.100 Additionally, de novo osteosarcomas tend to have a later onset.100

Osteosarcomas are generally manifested as localized, painless, expansile masses.1,100,102 Patients with tumors attaining large size or involving the skull base may complain of local tenderness, headaches, proptosis, ophthalmoplegia, facial weakness, decreased hearing ability, or tinnitus.100,101,103,106 Although extensive bony destruction can occur, the dura, brain, and venous sinuses are only rarely involved.10 The alkaline phosphatase level may be a useful diagnostic test; in a patient with known fibrous dysplasia, elevation of alkaline phosphatase may signify malignant transformation.100,103,105

Histologically, osteogenic sarcomas consist of a sarcomatous spindle cell stroma with an associated osseous component.1,101,103 The stromal cells demonstrate varying amounts of anaplasia and pleomorphism.1 Formation of bone or osteoid by the tumor cells is required for diagnosis.11,26 Necrosis may be present as well.99,102 A low-grade, well-differentiated subtype of osteosarcoma has been reported.101

Osteosarcomas may be either osteoblastic, osteolytic, or mixed, and their radiologic appearance is contingent on the relative amounts of each subtype.11,100,103 Osteoblastic lesions appear more sclerotic, and osteolytic lesions appear more radiolucent.103 Mixed, predominantly osteoblastic lesions are most common.100 CT is helpful in determining the amount of bony involvement.11,100 The classic appearance on radiography and CT consists of bony destruction, cortical expansion, and a “sunburst” periosteal reaction.101,104 CT may also demonstrate areas of irregular calcification, as well as low-attenuation areas representing necrosis.102 MRI generally demonstrates a heterogeneous signal on both T1- and T2-weighted sequences and may be helpful for determining the presence of intracranial invasion.11,100,102 Contrast enhancement is typically heterogeneous.101 A radionuclide bone scan may show increased uptake of radioactive material by the tumor.11,99 Angiography, when performed, demonstrates pathologic feeding of the lesion by branches of the ECA.100,102,106

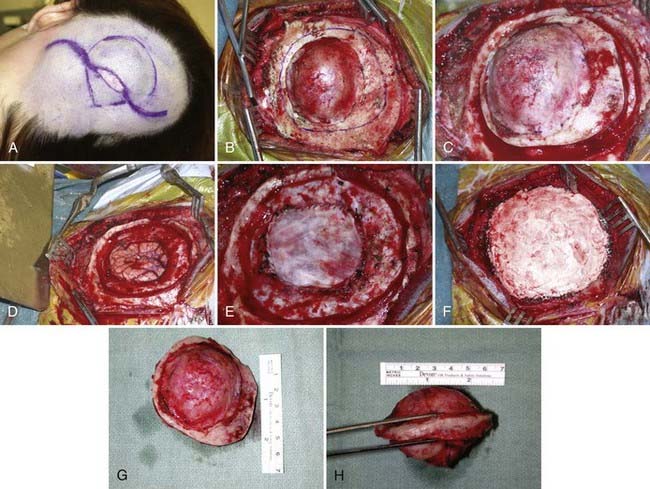

Gross total resection of osteosarcoma is the ideal treatment when safely attainable.99,102,103 Local tumor recurrence is common after partial resection (Fig. 148-4).99 Preoperative embolization may be a helpful surgical adjunct.102,106 Osteosarcomas are relatively radioresistant, although some surgeons recommend irradiation of any residual tumor after partial resection.99,100,105 Several groups have reported a dramatic increase in patient survival rate with the addition of chemotherapy.99,100,102,107 Salvati and coworkers reported an increase in the 2-year survival rate from 15% to 17% to 55% to 60% with the addition of chemotherapy.100 Chennupati and associates reported that a chemotherapeutic regimen of methotrexate, doxorubicin, and cisplatin increased the 5-year survival rate from 20% to between 60% and 70%.99 Sundaresan and colleagues advocated neoadjuvant treatment with this same regimen.107 The low-grade well-differentiated subtype of osteosarcoma is relatively chemoresistant.101

Although osteosarcomas of the skull tend to metastasize later than those arising in other primary sites, distant metastases will develop in 7% to 17% of patients.99 This figure is closer to 10% with the low-grade well-differentiated subtype, and the prognosis for this subtype is better.101 Although systemic metastases are a common cause of death in patients with osteosarcoma arising from the long bones, local recurrence is more commonly the cause of death in those who have skull osteosarcomas.106 Metastasis to extracranial sites should be regarded as a treatable rather than a terminal event.100 The lungs are the most common site of distant dissemination.99,100,102,106 Accordingly, post-therapeutic imaging surveillance should include chest radiography or CT.99 Spinal metastases have also been reported.106 Because some cases of osteosarcoma in the skull are, indeed, metastatic to that location from an extracranial primary site, a comprehensive survey of the body is mandatory with this disease (Fig. 148-5).

The extent of intracranial involvement by osteosarcoma at the time of diagnosis is thought to be the most important prognostic factor.102,106

Fibrosarcoma

Fibrosarcoma is a rare, malignant tumor that may arise from degeneration of a preexisting lesion such as a fibroma1 or from Paget’s disease,10,108 or it may occur after radiation treatment.10,108–110

Fibrosarcomas are typically indolent, asymptomatic masses,1,111 although lesions at the base of the skull may be associated with cranial nerve palsies.10 Extension into the dura or brain parenchyma is uncommon.10 Fibrosarcomas are the most common type of sarcoma to arise as a late complication of irradiation of pituitary adenomas.109,110

Histologically, these lesions are characterized by interlaced bundles of spindle cells and collagen fibers in a “herringbone” pattern.26,108 There is no associated osteoid or bone formation.108,109 Fibrosarcomas are very cellular malignant lesions with elevated mitotic activity.26,108,109 They can generally be divided into three categories: low grade (most differentiated), moderately differentiated, and poorly differentiated.1 Cellularity and mitoses are both increased in the latter category.1,108,109 Necrosis may be present as well.10,109 Degeneration of a low-grade fibrosarcoma to a more malignant osteogenic sarcoma has been reported.109

Fibrosarcoma is often seen on imaging studies as a lytic lesion with cortical destruction or expansion, or both, and soft tissue extension.11,108,111 These tumors are generally periosteal in origin.10 Fibrosarcomas are frequently radiolucent because there is no bone formation or calcification.108 Alkaline phosphatase levels are not typically elevated, which may help distinguish this lesion from osteogenic sarcoma preoperatively.108 However, CT may demonstrate extensive bony destruction.111 MRI is helpful in determining the presence of intracranial extension.111 Peripheral contrast enhancement of the tumor may be noted on CT or MRI.111 Angiography may demonstrate tumor feeding by branches of the ECA.111

Fibrosarcoma appearing in childhood, including the congenital subtype, is a somewhat distinct clinical and histologic entity.111 Childhood fibrosarcoma tumor cells are more primitive and rounded and less pleomorphic than the adult type.111

En bloc surgical resection is generally the treatment of choice in both adults and children when feasible.108,111,112 Neoadjuvant chemotherapy or irradiation, or both, may be necessary when en bloc resection is not attainable.111,112 In adults, good tumor control has been reported with radiation therapy after incomplete tumor resection.113

Chondrosarcomas and Chordomas

Chondrosarcomas and chordomas are rare, slow-growing, infiltrative tumors of the skull base.114–117 They are pathologically distinct entities, although both have a natural history of indolent expansion, local invasion, and relentless recurrence.114,116,118 Chordomas are more common and tend to have a worse prognosis than low-grade chondrosarcomas.114,116,118,119 The 5-year survival rate in one series was reported to be 90% for chondrosarcomas and 65% for chordomas of the skull base.115 Chordomas are more commonly found at the midline in the clivus and cause brainstem compression, whereas chondrosarcomas are typically found away from the midline and give rise to cranial neuropathies.118,120,121 The chordoma subtype “chondroid chordoma” may be difficult to distinguish pathologically from low-grade chondrosarcoma, and such distinction is a matter of controversy.10,118

Chondrosarcoma

Chondrosarcoma is a malignant neoplasm of cartilage.1,10,116 The histologic origin of this tumor is unclear, and it originates either from primitive mesenchymal cells or from embryonic rests of the cartilaginous matrix near fused joints such as the petroclival fissure.114,116,118,120

Chondrosarcomas may cause extensive bone destruction, in addition to invading the middle and posterior fossae.10 Patients typically have headaches and cranial neuropathies, particularly abducens palsy.10,114,116,120 Lesions of the skull convexity may be manifested as painless expanding masses.1 Although chondrosarcomas typically arise de novo, progression from chondroma to chondrosarcoma has been documented.10,26,58 Additionally, multiple enchondromatosis type 1 (Ollier’s disease) predisposes patients to the development of chondrosarcoma.122

The malignant potential of chondrosarcoma is variable,10 but regardless, the prognosis is generally poor as a consequence of its relentless tendency for local recurrence.1

Chondrosarcomas are subclassified as “myxoid” (“conventional low grade”), “dedifferentiated,” and “mesenchymal,” with the myxoid type being the most common.114,118 Histologically, chondrosarcomas are hypercellular with hyperchromatic and pleomorphic nuclei.1 Multinucleate cells may be present.1 The hypercellular small cell component is interspersed with islands of hyaline cartilage.26 Histologically, the small cell element closely resembles hemangiopericytoma, with staghorn vasculature and intercellular reticulin staining.26

At times it may be difficult to differentiate chondrosarcoma from chondroid chordoma, particularly when the tumor arises from the midline.26,115 Unlike chondroid chordoma, however, chondrosarcomas are nonreactive for keratin and epithelial membrane antigen.26,114

On MRI, chondrosarcomas are usually lobulated lesions that appear isointense to hypointense on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on T2-weighted images and show heterogeneous contrast enhancement.116,119 This appearance is very similar to that of chordomas, but chordomas are more commonly found in the area of the clivus, whereas chondrosarcomas are more typically located off the midline.116,119 CT and radiography may demonstrate calcifications and ossifications within the tumor mass.11 Angiography may reveal extensive vascularity and an attendant tumor blush in higher grade lesions.11

Surgical resection followed by adjuvant radiotherapy is the treatment of choice for chondrosarcomas of the skull.114,115,120 The goal of gross total resection is often difficult to achieve because these tumors infiltrate the critical structures of the skull base.117 Even with multimodality therapy, recurrence is the norm and translates into a poor overall survival interval.119

Although chondrosarcomas are generally believed to be relatively radioresistant, some form of radiation treatment is typically part of the therapeutic regimen.116,119

Two groups have recently reported good results with the use of stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) as a postoperative adjunct for these lesions.117,120 Using postoperative SRS for residual or recurrent chondrosarcoma, Martin and coauthors reported a 5-year local control rate of 80% (±10%).120 They further speculated that SRS may be used in some cases as the primary treatment modality without surgery.120 Hasegawa and colleagues found that SRS was a useful postoperative adjunct, provided that the residual tumor volume was less than 20 mL.117

al-Mefty and coworkers reported good results without the use of postoperative radiotherapy in cases in which gross total resection was achieved and the tumor was found to be of the conventional low-grade histologic type.118 They did caution that this would not be the ideal treatment for patients with the dedifferentiated or mesenchymal types.119

Proton beam adjuvant therapy may be helpful, but ideal dosing for chondrosarcoma is still being determined.114,119

Chordoma

Chordomas are slow-growing tumors that arise from notochordal remnants.34,123–125 Chordomas of the skull most commonly occur at the skull base, with most arising from the clivus.1,121 These tumors may occur at any age, with the mean age being 36.9 years.1,11,116 As with skull base chondrosarcomas, most patients with chordomas have an abducens palsy and attendant diplopia. Headaches and lower cranial nerve palsies are also common findings.1,116,123,126 Pituitary dysfunction, torticollis, and cerebellar signs have been reported.121 Males are affected more frequently than females by a ratio of 2 : 1.11,127 These lesions typically form bulky, soft gray masses compressing the base of the brain and cerebellum.10 Although histologically benign, these tumors are locally invasive and generally portend a poor long-term prognosis.10,124 Untreated, a patient with a clival chordoma rarely survives for more than 30 months.128 Five- and 10-year survival rates with present treatment regimens are estimated to be 50% to 80% and 35%, respectively.127,129 However, the biologic behavior of these lesions is quite variable.129 Being female, experiencing tumor necrosis before radiation therapy, and having a tumor volume greater than 70 mL are all independent predictors of shortened overall patient survival.130 Some chordomas may be frankly malignant with metastatic potential.10,124 Metastasis is relatively uncommon, however, and occurs in 10% to 18% of patients and generally late in the clinical course.124,125 The danger arising from these “benign” tumors lies in their relentlessly recurrent, locally aggressive nature in the region of the vital structures of the skull base.123,125

Common chromosomal abnormalities include gains at specific regions of chromosomes 1, 7, and 19, as well as polysomy of chromosome 7.127,131 Immunohistochemical studies show that chordomas stain for S-100 protein, cytokeratin, and epithelial membrane antigen—the latter of which may be particularly helpful in distinguishing chordoma from chondrosarcoma.10,116,126

In gross appearance, chordomas are lobulated, gelatinous, semitranslucent gray masses.124,126 Histologically, chordomas are characterized by physaliphorous (“bubble-bearing”) cells, which also distinguishes them from chondrosarcomas.34,116 Cellular pleomorphism, mitoses, and hyperchromatic nuclei are uncommon and have little correlation with patient survival.124,125 Two percent to 8% of chordomas may contain regions of malignant mesenchymal tissue and are appropriately designated “dedifferentiated chordomas.”10,132

The classic finding on radiographs of skull chordomas is an expansile, lytic lesion of the clivus with periosteal elevation.124 Both soft tissue and osseous components are typically present.124 Chordomas usually appear isointense to hyperdense with variable heterogeneous contrast enhancement on CT.11 On MRI, chordomas appear isointense to hypointense on T1-weighted and hyperintense on T2-weighted images, with moderate to avid contrast enhancement.11,116 CT is useful for evaluation of bony destruction and tumor calcification—the latter being somewhat uncommon relative to chordomas of the sacrum.11,124,125 Angiography may be helpful in delineating the relationship of the tumor to the petrous carotid artery or the vertebral artery.126 Encasement or displacement of vascular structures may be noted, but significant stenosis is infrequent.11,129,133 The vascularity of the chordomas themselves is quite variable and may or may not demonstrate a blush on angiography.11,126 Again, the overall appearance is similar to that of chondrosarcomas, although chondrosarcomas are more typically found away from the midline.116

Surgical excision plays an important (and generally primary) role in the management of clival chordomas.123,126,129,132,134,135 Extensive resection has been associated with prolonged survival, but this must be balanced against the risk for increased morbidity with surgery.123 True “oncologic” resection is rarely achieved because of the invasive character of chordomas and their proximity to critical vessels and nerves.136 Although often described as soft and gelatinous, chordomas may be tough and fibrous at surgery; both consistencies can present a surgical challenge.137

Surgical approaches to clival chordomas include fronto-orbitozygomatic, zygomatic–extended middle fossa, transmaxillary, transcondylar, transbasal,123,138 and the transnasal, transsphenoidal approach, with or without endoscopic visualization.123,126,139 Additionally, DeMonte and associates described a transmandibular circumglossal retropharyngeal approach.137 Harsh and colleagues described a pedicled rhinotomy for a midface transnasal approach.121 Based on their location, al-Mefty and Borba divided chordomas into those that required only one skull base surgical approach (most cases in their series) and those that required combined approaches.123 Harsh and colleagues divided chordomas into those in the upper third of the clivus, which are best reached by a transnasal transsphenoidal approach; those in the lower third of the clivus, which require a transoral approach; and those lateral to the internal carotid artery or in the medial petrous bone, which require an additional lateral approach.121

At surgery, the tumor may be entirely extradural or may have eroded through the dura to become both extradural and intradural.121,126 The amount of intradural tumor may influence the surgical approach used.133 al-Mefty and Borba stressed the importance of drilling out the involved bone, as well as resecting the soft tissue mass.123 “Seeding” of the operative site with chordoma cells at surgery can occur unless the utmost care is taken during removal.140 Additionally, there is one reported case of an abdominal fat graft harvest site becoming seeded with chordoma.140 Leakage of CSF and cranial neuropathy are among the most common surgical complications.128,133,135 In experienced hands, most cranial nerve deficits associated with surgery tend to resolve with time.128

Because of the poor results obtained by treating chordomas with conventional radiotherapy, they were initially thought to be “radioresistant” tumors. The advent of more conformal, high-dose irradiation, particularly proton beam irradiation, has led to the standard use of postoperative radiotherapy.116,121,123,124,135,136 Surgical resection has been performed after irradiation but is typically more difficult because normal tissue planes are disrupted, which places vessels and nerves at greater risk.126,133,134 There is some disagreement regarding whether radiation therapy should be used in all cases postoperatively, when there is known residual tumor, or only at recurrence.121,123,128 A dose of at least 60 Gy is required for therapeutic effect.129 As it has become more available, proton beam radiotherapy is more commonly being used for residual or recurrent tumor.119,123,128,135 One large retrospective series found a 5-year survival rate of 79% for chordoma patients treated with proton beam radiotherapy after surgical resection.119 As with the Bragg peak of proton beam radiotherapy, SRS provides the ability to direct a high concentration of radiation to a well-demarcated area.129,135,138 Good results have been reported with the use of SRS for recurrent or residual disease.120,141 Additionally, Martin and colleagues have used radiosurgery as primary treatment in two patients.120

Chemotherapy is generally ineffective for the treatment of chordomas but may have a role in treatment of the dedifferentiated chordoma subtype.132

Recurrences of chordoma are common, but survival for as long as 46 years has been demonstrated in a poorly defined subset of patients.129,136 The risks associated with surgery are greater in patients who have previously undergone surgery or radiation therapy, or both.133,134

Secondary (Metastatic) Skull Neoplasms

Metastases are the most common neoplasms of the calvaria.142,143 Metastatic skull tumors have been reported from almost all types of primary cancer.142–151

Carcinoma

Carcinomas of the breast, lung, and prostate are, in that order, by far the three most common primary tumors causing skull metastasis; renal and thyroid carcinoma skull metastases are not uncommon.142,143,145,148,150–152 The incidence of skull metastasis in patients with breast, lung, or prostate cancer may be as high as 23%.152 Metastasis of carcinoma to the cranial vault, particularly to the occipital bone, is more common than metastasis to the skull base.146 Although metastases to the central skull base are uncommon, they occur more frequently than primary bone lesions in this area and are more likely to cause symptoms than metastases to the cranial vault.144 Metastases to the skull base may result in one of several defined syndromes based on tumor location.153,154 Anterior skull base lesions may cause orbital syndrome, which is manifested by orbital pain, exophthalmos (or less commonly, enophthalmos), decreased visual acuity, periorbital swelling, and external ophthalmoplegia. Middle skull base lesions may cause parasellar, middle fossa, or temporal bone syndromes. Parasellar (sphenocavernous) syndrome is manifested as ocular paresis, papilledema, and facial pain or numbness. Middle fossa (gasserian ganglion) syndrome is characterized by pain and numbness in the V2 and V3 distributions, pterygoid and masseter weakness, and possible abducens palsy. Temporal bone syndrome consists of hearing loss, otalgia, periauricular swelling, and facial weakness. Posterior skull base metastases may cause jugular foramen or occipital condyle syndromes. Jugular foramen syndrome is manifested by the involvement of various combinations of cranial nerves IX to XII and results in dysphagia, hoarseness, tongue atrophy, sternocleidomastoid/trapezius atrophy, and Horner’s syndrome. Occipital condyle syndrome affects cranial nerve XII and is characterized by tongue weakness and atrophy, occipital or nuchal pain, dysarthria, and dysphagia. In a patient with a known cancer diagnosis in whom cranial neuropathies or facial pain develops, a skull base metastasis must be suspected and investigated.153,154

Lung, breast, renal, hepatic, and thyroid metastases are more typically associated with lytic bone destruction as seen on radiography and CT, whereas prostate cancer metastases are more commonly sclerotic.11,144,146,148,153,154 MRI demonstrates a hypointense lesion on T1-weighted images, with variable T2 signal characteristics and variable contrast enhancement.147,153 The inclusion of diffusion-weighted imaging sequences improves the sensitivity for detecting nonprostatic (nonsclerotic) skull metastasis.152 Radionuclide bone scanning is a particularly sensitive method for detecting skull metastasis.143,144,146,153,155 Single-photon emission computed tomography is better than bone scintigraphy in helping to differentiate between malignant and inflammatory skull masses.154 Examination of CSF may be particularly helpful in assessing a suspected metastasis to the skull base. If CSF is normal, metastasis is more likely than infection to be the cause of multiple cranial neuropathies.154 A CSF study may also reveal the presence of meningeal carcinomatosis.153 Typically, angiography is performed only if surgery is likely to be performed, the tumor is hypervascular, and preoperative embolization is required.155

Patients with skull metastases are frequently at an advanced stage of their primary disease, and years may have elapsed since their original diagnosis.143,145,150,153,154 These lesions are often asymptomatic. Surgery may not be required for diagnostic or even therapeutic purposes.155 Less frequently, a symptomatic or palpable skull mass may be the first sign of the underlying cancer.144,145 In such cases, surgical resection may be helpful in establishing a tissue diagnosis, but fine-needle aspiration provides the diagnosis without surgical risk when the skull lesions are multiple or when a tumor is too small or too indolent to need resection.144,155

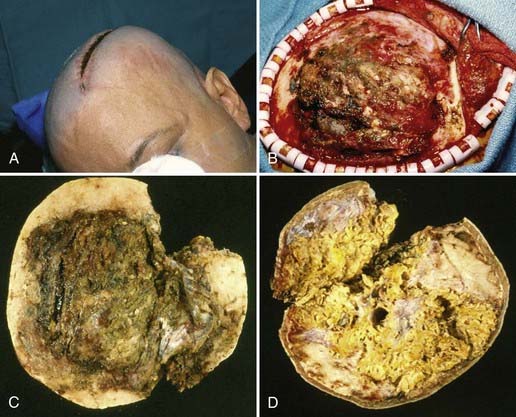

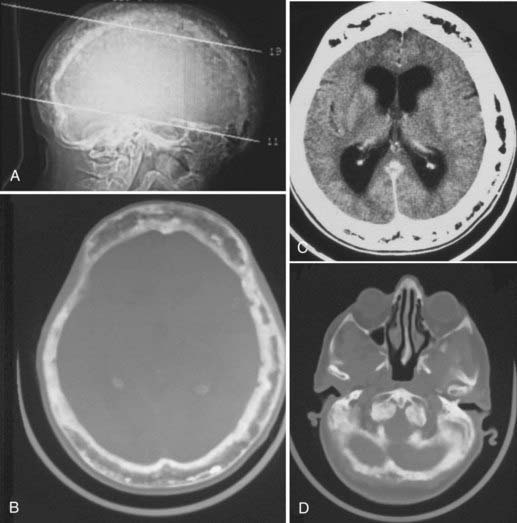

Most skull metastases are asymptomatic and are often found during staging evaluation for the primary disease (Fig. 148-6).142,143 Common symptoms that require treatment are pain, hemorrhage, skin ulceration, and intracranial growth that results in neurological deficits.142,143,147 Hemorrhage from a skull metastasis may produce an epidural hematoma.147,156 Involvement of a dural sinus may cause increased intracranial pressure by obstruction of venous outflow.142 Symptomatic patients may benefit from surgical resection as a palliative procedure.145,147 Survival, although predicated on the status of the systemic disease, is usually of sufficient duration to justify surgical treatment of the skull metastasis.143,155

Resection of metastases in the cranial vault is generally straightforward. Adherence to intracranial structures, particularly to the dural sinuses, may make surgery more difficult, however. Although the overlying scalp is occasionally involved, it will usually peel away cleanly from the tumor, which typically respects the galea. This maneuver interrupts small feeding vessels crossing from the scalp to the tumor. Ideally, a circumferential trough is then drilled, through which a circumferential dural incision allows potentially involved dura to be removed as part of the specimen and eliminates the remaining vascular feeders. In this way an en bloc resection is achieved with a rim of normal bone surrounding the tumor.142,148 The gradual, complete devascularization provided by this technique allows even the most vascular tumors (e.g., renal cell and thyroid carcinomas) to be removed with minimal blood loss and without embolization (Fig. 148-7). Such tumors should never be removed piecemeal or torrential blood loss may ensue. In addition, in keeping with basic neuro-oncologic principles, en bloc resection should theoretically decrease the rate of local recurrence.142,148 Michael and associates described their surgical technique for resecting symptomatic calvarial metastases involving the dural sinuses (Fig. 148-8).142 Bur holes are placed on the sinus both in front of and behind the lesion. Additional bur holes are placed lateral to the lesion. As the tumor is resected from the sinus, the sinus is sutured closed. Resection of the involved sinus may be necessary and is acceptable if it is already occluded or if the tumor has invaded the anterior third of the superior sagittal sinus or a nondominant transverse sinus; preservation of the surrounding cortical veins is of paramount importance.142

Treatment of metastasis to the skull base is contingent on the location of the metastasis and the nature of the primary tumor.153,154 Only a minority of patients with metastasis to the skull base are candidates for surgical resection.154 When surgery is planned and the skull base tumor is thought to be particularly vascular (e.g., hepatic, renal, or thyroid carcinomas), some form of preoperative embolization may be useful.151,155 However, typically, complete surgical resection is not feasible, and radiotherapy is the primary mode of treatment.153,154 Primary radiotherapy has been used more frequently as more conformal high-dose irradiation has become available.153,154

Solitary Plasmacytoma/Multiple Myeloma

Plasmacytoma is a solitary neoplasm of monoclonal plasma cells.157–161 A benign lesion, plasmacytoma may progress to its disseminated form, multiple myeloma, a malignant and potentially fatal disease.159,161 Plasmacytoma commonly affects patients in the late fifth decade, whereas multiple myeloma more frequently occurs in the late sixth decade.162 Although these lesions are more often found in the vertebral column, thoracic cage, and long bones, involvement of the cranial vault is not infrequent.163 Less common is involvement of the skull base, which is a strong positive predictor for progression from solitary plasmacytoma to multiple myeloma. A comprehensive evaluation is indicated in this situation.158,159,161

Plasmacytoma lesions may cause cranial nerve symptoms, orbital involvement symptoms, or symptoms of increased intracranial pressure.161 Lesions at the skull base may involve the cavernous sinus, petrous temporal bone, or sphenoid bone and thus are often accompanied by cranial neuropathies; abducens palsy with attendant diplopia is the most common.157,159,160,164,165 Additionally, cranial neuropathies may be caused by direct infiltration of the nerves with myelomatous cells.163,166 Involvement of the orbit may result in exophthalmos or ophthalmoparesis.161 Intracranial extension of plasmacytoma may cause headaches or other symptoms of increased intracranial pressure.159,160,162,167 Intradural extension may give rise to seizures.163

In gross appearance, plasmacytomas are typically smooth and lobulated but can cause irregular destruction of the involved bone.160 Viewed histologically, plasmacytomas are made up of abnormal plasma cells that produce monoclonal immunoglobulins.160 Immunologic staining typically demonstrates diffuse staining of monoclonal κ and λ light chains, which helps distinguish plasmacytoma from an inflammatory process. An excess of either type of light chain by a ratio of 16 : 1 or more strongly suggests the presence of plasmacytoma.157,158,160

Plasmacytomas may be of low, intermediate, or high grade based on histologic findings. Low-grade tumors (plasmacytic) appear very similar to normal, mature-looking plasma cells.158,161 High-grade tumors (plasmablastic) contain plasma cells with large vesicular nuclei, pale Golgi zones, prominent nucleoli, and a greatly elevated MIB-1 labeling index. Plasmablastic plasmacytomas may be associated with systemic multiple myeloma.158,161

As seen on plain radiography and CT, multiple myeloma is characterized by well-defined lytic lesions involving the diploë and cortical bone, without a sclerotic border (Fig. 148-9).11,158,160,163,164,168 MRI is helpful for determining the presence of any associated extraosseous component, as well as for determining the presence of flow voids because these lesions can be quite vascular.11,160,163,168 Lesions typically appear isodense to hyperdense on CT, isointense to hyperintense on T1-weighted MRI, and markedly hypointense on T2-weighted MRI sequences.162,163,168 Avid contrast enhancement on both CT and MRI is the norm.159,162,168,169 Plasmacytomas typically demonstrate restriction on diffusion-weighted images, whereas multiple myeloma will show increased diffusion.163 It is essential to perform both CT and MRI because the former delineates the osseous involvement whereas the latter demonstrates soft tissue involvement of the meninges or brain parenchyma.163 A “cold” lesion without tracer uptake is characteristic on radioisotope bone scanning168; however, scintigraphy has a relatively high false-negative rate and is of limited clinical utility.11 Angiography may demonstrate a tumor blush from ECA branch feeders.163,168 A thorough evaluation to exclude multiple myeloma is necessary (particularly if the lesion is found at the skull base) and includes bone marrow evaluation, a skeletal survey, a bone scan, and serum and urine protein electrophoresis.157,160

Optimal treatment of solitary plasmacytomas is surgical resection followed by irradiation,157,159,161,163,167 although some have reported good results with surgical resection alone.170 At surgery, these tumors are often found to be quite vascular, and significant blood loss should be anticipated. Preoperative embolization may be helpful.157,168 Given that plasmacytoma is a radiosensitive lesion, patients with prohibitive medical comorbid conditions or solitary plasmacytoma lesions of the skull base may best be treated with radiotherapy alone after biopsy.159,161,167 Bindal and coworkers found that patients who underwent resection of a solitary plasmacytoma followed by radiation therapy and in whom multiple myeloma did not develop in the postoperative period were unlikely to have multiple myeloma develop in the long term.159 They did stress that skull base lesions were unlikely to represent a solitary plasmacytoma and that a thorough evaluation for multiple myeloma is therefore warranted in this setting.159,161

Generally, skull lesions from multiple myeloma are not treated by surgical resection. Chemotherapy with C-VAD (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, Adriamycin, and dexamethasone), along with stem cell transplantation and palliative irradiation, forms the mainstay of treatment of multiple myeloma.157,158,160,163 Thus, skull base lesions are less likely to undergo surgical resection because a more morbid procedure is required and the patient is more likely to carry a diagnosis of systemic multiple myeloma, which has a median survival time of 3 years (range, several months to 10 years).157,161,163

Lymphoma

Lymphoma in the cranial vault is rare.171,172 Bone lesions occur in 7% to 25% of patients with lymphoma, but bone is the primary location in just 3% to 4% of patients.173,174 Bone involvement often occurs late in the disease course.175 When lymphoma is present in bone, the spine is the most common location. Calvarial involvement is uncommon, although somewhat less so in immunocompromised patients.174,174 Cranial vault involvement by a true primary skull lymphoma is less common than a skull deposit from disseminated systemic lymphoma.173,176,177 Therefore, if a solitary focus of lymphoma is found in the skull, a thorough evaluation for systemic disease is essential.173

Typical initial symptoms of skull lymphoma include a painless palpable lump and symptoms of increased intracranial pressure from intracranial-to-extradural dissemination or bone destruction (Fig. 148-10).171,174 Rare intradural extension may lead to seizures, focal neurological deficits, or altered mental status.174,175,177,178

Most lymphomas that involve the cranial vault are of the monoclonal B-cell type.176,178 Histologic study of lymphomas shows diffuse growth of atypical lymphocytes.171,172,176 Large immunoblastic cells with prominent central nuclei may be seen.176 Tests for immune markers such as CD20 and CD79 may be positive,171,172,175 and the MIB-1 labeling index may be elevated.175

Cranial vault lymphomas usually have a significant soft tissue component with very little cortical bone destruction. Plain radiography and CT may demonstrate a lytic lesion,173,175,179 but more typically, the tumor diffusely permeates the bone.171,172,174,176,178 On MRI, these tumors appear hypointense on T1-weighted and hyperintense on T2-weighted sequences and often exhibit homogeneous contrast enhancement.171,174,179 MRI with contrast enhancement may also demonstrate meningeal involvement.172 Dural thickening may be noted beneath the calvarial lesion, but intradural invasion is rare.173,174,176,179 Skull lymphoma readily takes up tracer on scintigraphy studies.174 The findings from angiography generally show these lesions to be relatively avascular.171,177

Treatment involves systemic chemotherapy with an Adriamycin-containing regimen (cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunomycin, Oncovin, prednisone [CHOP] protocol) and local radiotherapy.171,172,174,175,177 The 5-year survival rate is reported to be 40% to 60%.172,174 Although some recommend surgically resecting the tumor before administering radiotherapy and chemotherapy, we do not.171,174,176

Ewing’s Sarcoma

Ewing’s sarcoma is a highly malignant bone tumor that typically affects the pelvis and the long bones of the lower extremities in children and young adults.180,181 It is the second most common malignant bone tumor in childhood (after osteosarcoma).182 Although primary involvement of the skull is rare,181,182 metastases to the cranium are not infrequent.180 Ewing’s sarcoma typically grows extradurally and often reaches a very large size before dural invasion or clinical detection, or both.181,183 Symptoms tend to develop as a result of dural invasion, hydrocephalus, or raised intracranial pressure. Headaches and scalp swelling are the most common symptoms, and papilledema is the most common sign.180,184 Males are affected more than females by a ratio of 1.8 : 1.181,182 Approximately 90% of cases occur in the first 2 decades of life. The mean age in one series was 14.5 years, with the range being 18 months to 40 years.181

Ewing’s sarcoma can be considered an undifferentiated form of peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET).34,183 Histologically, these tumors are characterized by sheets of small round blue cells with an increased nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio.180,181,183,184 Pseudorosettes may be present, but sheets of cells are more characteristic.181,185 Mitoses are common. Bony spicules may be present, and CD99 and vimentin may be expressed.180,181,183,184,186

Plain radiographs of the skull may reveal layering of bone in an “onion peel” arrangement, with layers of bone mottling and erosion, as well as new bone formation.34,180,181 This distinctive periosteal reaction and calcification may also be noted on CT.182,183 In some cases, the tumor will simply be manifested as a lytic lesion on plain radiographs and CT.181,182 MRI may show heterogeneous signal characteristics and avid contrast enhancement of any associated soft tissue component.180,182,184 MRI is less essential than CT in the assessment of these tumors.180,181,183 Ewing’s sarcoma exhibits increased radioisotope uptake in nuclear bone scanning images. Scintigraphy is particularly helpful in detecting the presence of any extracranial lesions.181,182,187

Surgical resection plays an important role in the management of cranial Ewing’s sarcoma.181,182,184,186,188 The dura should be inspected for tumor infiltration, and if infiltration is noted, the dura should be resected as well.181 It is not uncommon for these patients to undergo fairly emergency surgery at the time of diagnosis because of the large size of the lesion and signs and symptoms of increased intracranial pressure.183 Ewing’s sarcoma is often highly vascular, and the potential for excessive blood loss should be anticipated before surgery.181,184 Local recurrence after resection has been reported.181,184

Adjuvant therapy after resection, including radiotherapy and chemotherapy, is essential.180,182 Adjunctive chemotherapy with a combination of vincristine, cyclophosphamide, cisplatin, etoposide, dactinomycin, and doxorubicin has raised the overall 5-year survival rate from 5% to 10% to 50% to 60%.182,183

Although improved by treatment regimens, the prognosis for many patients with Ewing’s sarcoma continues to be poor because of early metastasis to the lungs and to other bones. This early metastasis is less common in cases of primary Ewing’s sarcoma, and thus primary Ewing’s skull tumors carry a better prognosis.180,182,184,188

Neuroblastoma

Neuroblastoma is a malignant tumor that originates in the sympathetic nervous system and accounts for 10% of childhood malignancies, with 75% of them occurring in children younger than 4 years.189,190 It is the second most common solid tumor in children and the most common in infants.191 At diagnosis, 65% of patients have disseminated disease, most commonly spreading to bone.191 Disseminated disease is typically manifested as fever and bone pain.192 Additionally, neuroblastoma is associated with a paraneoplastic syndrome of opsoclonus/myoclonus (“dancing eyes and feet syndrome”).34,192

Neuroblastoma is the most common metastasis found in the skull in children, and detection of it there may precede diagnosis of the primary tumor.193,194 The rate of metastasis to the skull in patients with neuroblastoma has been reported to be as high as 40%, and such tumors often diffusely involve the calvaria and skull base.193 Skull metastases from neuroblastoma are usually multiple, with frequent involvement of the sphenoid and other bones forming the orbit.189,195 Headache is the most common complaint, although many patients are asymptomatic.193 These headaches frequently resolve after radiotherapy.193 Metastases to the orbital bones and periorbital tissues may cause ecchymoses or “raccoon eyes,” which may be mistaken for a sign of traumatic skull base fracture.190,192,195 With growth, the tumor deposit may invade the dura and cause signs and symptoms of increased intracranial pressure.11

Cerebral neuroblastoma is a PNET that displays neuronal differentiation in the form of immunopositivity for synaptophysin and other neuronal markers.34,194 Giemsa staining of histologic sections demonstrates sheets of neuroblasts (small round blue cells with large dark nuclei, small nucleoli, and little cytoplasm) and Homer Wright rosettes.189,192,194 Molecular biology studies have demonstrated N-myc amplification in a third of these tumors.34

Neuroblastoma is generally widely metastatic to the skull, with expansion of the bone, extension into the epidural space, and splaying of cranial sutures. Accordingly, the patient’s enlarging head may raise suspicion of hydrocephalus; however, subsequent imaging studies reveal normal brain and ventricle size.196

Plain radiography and CT demonstrate a destructive mass growing inward from the skull along with bone spicules radiating outward in a classic “sunburst” appearance and elevation of the periosteum.189,194,195,197 In children, neuroblastoma often seems to metastasize directly to the cranial sutures with resultant suture diastasis. This may occur because of the increased vascularity of these sutures in children.11,189 On MRI, neuroblastoma metastases appear as masses within the calvaria that have the intensity of soft tissue and show contrast enhancement.194,197 Bone scintigraphy demonstrates increased uptake of radioisotope by the lesion.190,194,195

Neuroblastomas are very radiosensitive and chemosensitive and are treated with a combination of radiotherapy and chemotherapy, with surgery generally being unwarranted.189,193 Reports on relapse have suggested that more aggressive management is necessary in the setting of skull metastases.191 However, cranial irradiation is problematic in this young patient population.193 Recently, Wolden and colleagues described encouraging results with the use of “brain-sparing radiation therapy” in such patients.193 Because relapse remains common despite multimodality treatment, the 5-year survival rate is 10% to 30% in children older than 1 year and 55% in infants younger than 1 year.191

Reactive, Proliferating, and Non-Neoplastic Lesions

Paget’s Disease of Bone (Osteitis Deformans)

Paget’s disease of bone is a disorder characterized by the uncoupling of bone formation and resorption, with resultant bone thickening and weakening.198–201 This excessive and abnormal bone remodeling is of unknown origin but is hypothesized to be caused by a slow virus infection.198,202 The disease affects 3% of persons older than 40 years and 10% of persons older than 85 years.202–204 Paget’s disease is 1.5 times more common in men than women.204 Alkaline phosphatase and hydroxyproline levels are elevated.201,205,206

The skull is the second most common location after the pelvis for this disease and is involved in 65% to 70% of cases.204 Most commonly, patients are asymptomatic or complain of localized bone pain. As the disease progresses, the headaches that it produces can become more constant, generalized, and severe.207,208 Involvement of the skull base by Paget’s disease can cause cranial neuropathy.199,203,204 Mixed low-frequency conductive and high-frequency sensorineural hearing loss is a common finding when the temporal bone is included in the affected area.198,207,209 Involvement of the sphenoid bone was thought to have caused endocrinopathy in one case.210

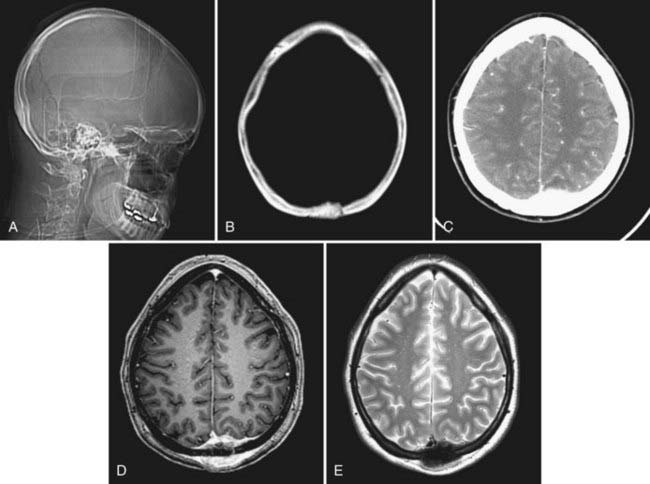

With cranial vault involvement, the skull becomes quite spongiose and thickened.11,201,202,208 Despite its increasing size, the skull is actually weakened.1,199,201 If the skull base is involved, it may settle and result in platybasia or basilar invagination in a third of cases (Fig. 148-11).199,202,203,209,211 Because the skull in patients with Paget’s disease is both more fragile and more vascular than normal bone, patients with Paget’s disease are more prone to develop an epidural hematoma should they experience head trauma. This may occur even without an associated fracture.199,201

Paget’s disease has three phases: (1) the “destructive,” “vascular,” or “osteolytic” phase, marked by resorption of bone, which is replaced by fibrous connective tissue and vascular channels; (2) the “mixed” osteoclastic/osteoblastic or “reparative” phase as the bone begins to smooth over but remains somewhat disrupted by vascular channels; and (3) the “quiescent,” “sclerotic,” or “osteoblastic” phase, wherein distinction between the cortex and the diploë is lost.198,204,208

As seen histologically, in the early phases, large quantities of new bone form in a loose, vascular, connective marrow.1,204 Later, simultaneous osteoblastic and osteoclastic activity may be seen.1 A mosaic of lamellar bone of various stages is the result.212

Imaging characteristics correspond to the aforementioned three phases. As seen on plain radiography and CT, lesions can appear to be lytic, sclerotic, or mixed. The initial appearance of the lesion on plain radiographs and CT is radiolucent. As the disease progresses and bone condenses, areas of sclerosis mix with the preexisting lytic areas, and a mottled “cotton wool” appearance develops.199,206,209 With disease progression, the inner table becomes thicker than the destroyed outer table of cortical bone, and the diploë expands.202,204 Paget’s lesions show mixed intensity on MRI. In the active phase of the disease, vascular channels are present. As the disease progresses, the distinction between cortical bone and marrow is blurred.204,204 Paget’s disease is detected earlier by bone scintigraphy than by plain radiography or CT.207

Radiologic differentiation between Paget’s disease and fibrous dysplasia can be challenging. Paget’s disease is often symmetrical, whereas fibrous dysplasia tends to be unilateral, even in polyostotic cases. Paget’s disease is accompanied by thickening of the inner cortical table, whereas fibrous dysplasia may show cortical destruction. Additionally, Paget’s disease does not display the “ground glass” appearance on CT that distinguishes fibrous dysplasia. Finally, fibrous dysplasia much more commonly involves the orbit, the paranasal sinuses, and the sphenoid bone than Paget’s disease does.204 With respect to epidemiology, the population affected by Paget’s disease is older than that affected by fibrous dysplasia.204

Medical treatment with bisphosphonates or calcitonin is the first line of treatment of Paget’s disease.207,210 Subjective symptoms of headache, tinnitus, and vertigo typically improve in response to medical management, but objective audiometric response does not.207 In the rare case in which surgery is indicated, the possibility of significant hemorrhage must be anticipated.199,201

In 10% to 22% of patients, Paget’s disease of the skull will eventually undergo sarcomatous degeneration, although this figure may be much lower in asymptomatic patients with minimal disease.10,205,206,209,211 The most common types of sarcomatous degeneration are to osteosarcoma (50% to 60% of instances) and fibrosarcoma (20% to 25% of instances).10,206 In other cases, Paget’s disease may progress to form a giant cell tumor. Alkaline phosphatase levels should be obtained to monitor for disease progression or recurrence.201,205,208 Development of a soft tissue mass should raise suspicion for sarcomatous degeneration; a simple needle biopsy should then be performed.206 The prognosis for an osteosarcoma arising from a Paget lesion is worse than that for an osteosarcoma arising de novo.207

Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (Histiocytosis X)

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) refers to a group of related disorders of abnormal uncontrolled histiocyte proliferation: eosinophilic granuloma, Hand-Schüller-Christian disease, Abt-Letterer-Siwe disease, and Hashimoto-Pritzker disease.2,213 Although adult cases have been reported,214 LCH predominantly occurs in children and adolescents, with the mean age at incidence being 12 years.3,213 Manifestations of LCH are diverse, and many organs may be affected, including bone (involved in 80% to 95% of cases), lung (the most common nonosseous site), liver, skin, hypothalamus, posterior pituitary, and the lymphatic system.3,4,215

The clinical manifestation of LCH is contingent on the location and extent of proliferation of the pathologic Langerhans cells.2 The most common and simplest form of LCH is a solitary lytic lesion of bone designated eosinophilic granuloma, which accounts for 60% to 80% of cases. The skull is the most commonly involved bone.4–6,213,215 Patients with such solitary lesions usually exhibit localized bone pain or a palpable mass.3,6,215 Patients with disseminated disease may have skin lesions, diabetes insipidus, or lymphadenopathy.3,214 Lesions at the skull base have been reported to cause cranial neuropathies.5,216

The cause of LCH is unknown.1,213 It is unclear whether LCH is merely a reactive overproliferation of otherwise normal cells or whether the Langerhans cells are abnormal and represent either a benign or malignant neoplastic process.3,215 One theory holds that it is a reactive proliferation of polyclonal cells, which suggests a disorder of immune regulation.5,216 Some specimens, however, demonstrate monoclonal proliferation, which suggests that LCH may in fact be a neoplastic process.3 There is also recent speculation that LCH may be initiated by Epstein-Barr virus.2