45

Skin Signs of Systemic Disease

Introduction

• With the exception of endocrinologic disorders and paraneoplastic dermatoses, most of these skin signs have been discussed in other chapters – for example, pyoderma gangrenosum in Chapter 21, telangiectasias of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome) in Chapter 87, and sebaceous neoplasms of Muir–Torre syndrome in Chapters 52 and 91.

Pulmonary Disease and the Skin

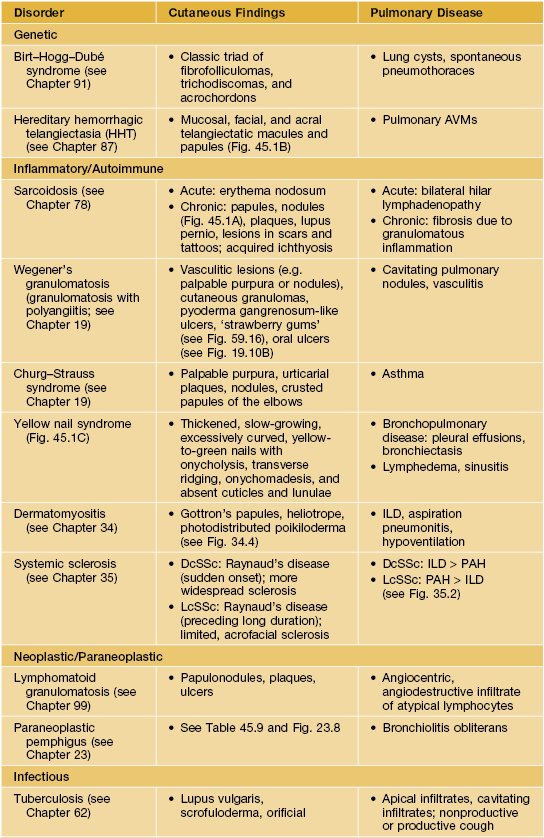

• Table 45.1 and Fig. 45.1.

Table 45.1

Examples of skin signs of pulmonary disease.

* Primary pulmonary infection also occurs in other systemic mycoses due to dimorphic pathogens, including coccidioidomycosis, histoplasmosis, and paracoccidioidomycosis.

AVM, arteriovenous malformation; DcSSc, diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis; LcSSc, limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis; ILD, interstitial lung disease; PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension.

Fig. 45.1 Skin signs of pulmonary disease. A Periorificial and facial papules of sarcoidosis. The presence of lesions on the nasal rim is often associated with granulomatous inflammation of the upper respiratory tract. B Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Multiple small bright red macules and papules on the tongue and lips. C Yellow nail syndrome. A, B, Courtesy, Jeffrey P. Callen, MD; C, Courtesy, Karynne O. Duncan, MD.

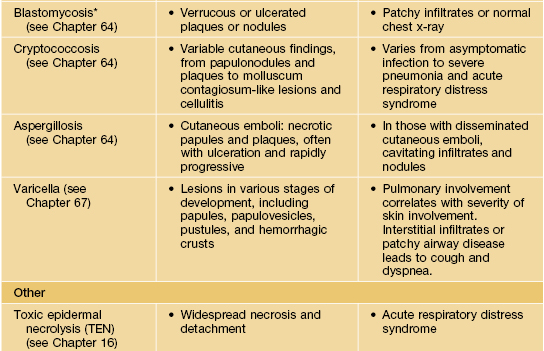

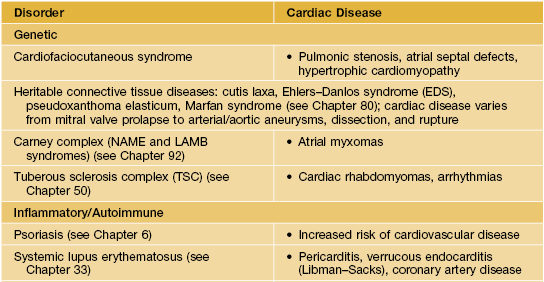

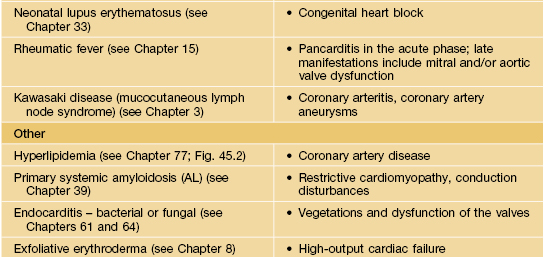

Cardiac Disease and the Skin

• Table 45.2 and Fig. 45.2.

Table 45.2

Examples of skin signs of cardiac disease.

The cutaneous features of these disorders are discussed in the chapters cited. Cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome is characterized by generalized ichthyosis-like scaling, keratosis pilaris, café-au-lait macules, sparse curly hair, and developmental delay.

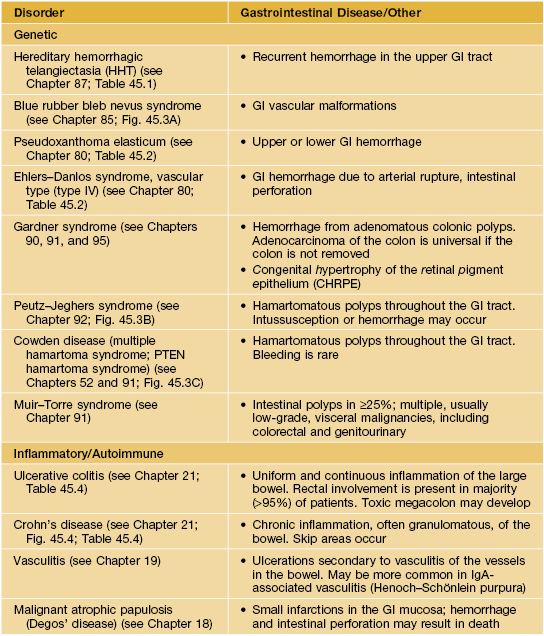

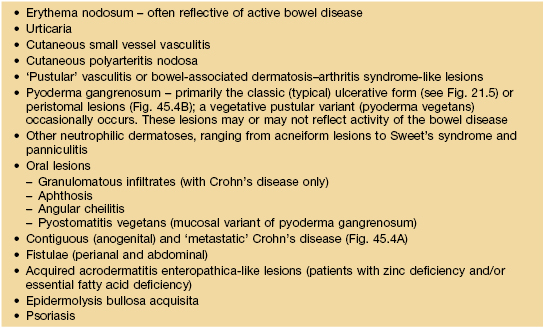

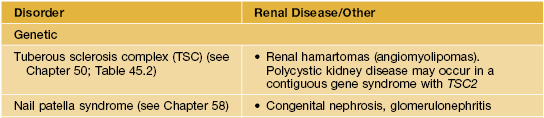

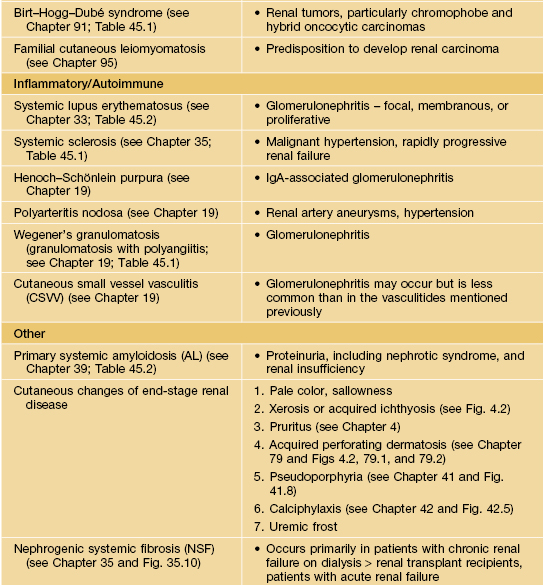

Gastrointestinal Disease and the Skin

• Tables 45.3–45.5 and Figs. 45.3 and 45.4.

Table 45.5

Peristomal skin disorders.

Peristomal skin disorders are common and may limit use and efficacy of the stoma appliance. When the etiology is uncertain, evaluation can include KOH examination, microbial cultures, patch testing, and histologic examination.

| Skin Disorder | Comments |

| Irritant contact dermatitis | Most common cause of peristomal dermatitis, especially in patients with an ileostomy. Primarily attributed to exposure to feces or urine |

| Pre-existing skin disease (e.g. psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis) | Exclude primary contact dermatitis or infection or superimposed contact dermatitis |

| Cutaneous infection (Candida spp. dermatophyte, herpes-virus [primarily simplex], bacteria [especially Staphylococcus aureus]) | Colonization with bacteria and/or yeast is common. Recent treatment with antibiotics predisposes to candidiasis. May initially improve and then worsen if treated inappropriately with topical corticosteroids |

| Allergic contact dermatitis | Relatively uncommon. Potential allergens include adhesive pastes, adhesive ring or wafer of stoma bag, ostomy bag, epoxy resin, rubber, lanolin, and fragrances. Patch test with both standardized allergens and patient’s own products |

| Pyoderma gangrenosum | Infrequent cause of peristomal dermatitis; most common in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (Fig. 45.4B) |

| Pseudo-verrucous papules and nodules | Seen more commonly in association with urostomies; may be misdiagnosed as verrucae |

Adapted from Lyon CC, Smith AJ, Griffiths CE, et al. The spectrum of skin disorders in abdominal stoma patients. Br. J. Dermatol. 2000;143:1248–1260.

Fig. 45.3 Skin signs of gastrointestinal disease. A Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome. Several venous malformations are evident on this patient’s tongue. B Peutz–Jeghers syndrome. Multiple brown macules on the lips and oral mucosa. C Gingival cobblestoning in Cowden disease. This patient also had trichilemmomas and a ‘Cowden’s nodule’ or sclerotic fibroma on the neck. Courtesy, Jeffrey P. Callen, MD.

Fig. 45.4 Skin signs of inflammatory bowel disease. A ‘Metastatic’ Crohn’s disease. Non-contiguous granulomatous inflammation of the skin manifested by deep inflammatory fissures in the inguinal folds. B Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum in the setting of inflammatory bowel disease. Patients with ostomies, particularly ileostomies, are at risk for peristomal dermatoses, including pyoderma gangrenosum. Courtesy, Jeffrey P. Callen, MD.

Liver Disease and the Skin

• Table 45.6 and Fig. 45.5.

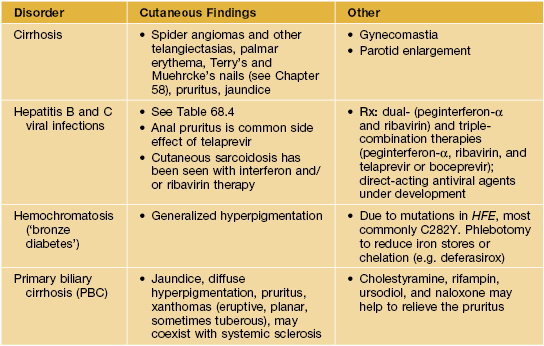

Table 45.6

Examples of skin signs of liver disease.

CSVV, cutaneous small vessel vasculitis; HCV, hepatitis C.

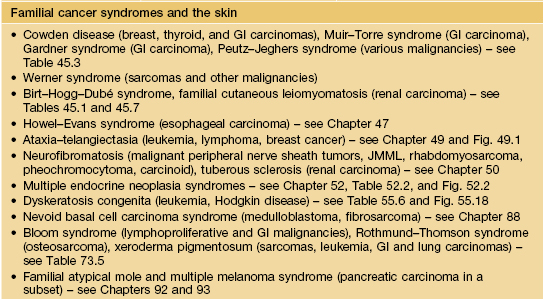

Skin Signs of Internal Malignancy

• Tables 45.8 and 45.9 and Figs. 45.6 and 45.7.

Table 45.8

Criteria used to associate a dermatosis and malignancy (Curth’s postulates).

| Concurrent onset | The neoplasm is discovered at the time of diagnosis of the dermatosis or shortly following diagnosis |

| Parallel course | Therapy of the malignancy results in disappearance of the dermatosis, and, if the malignancy recurs, then the dermatosis relapses |

| Uniform site or type of neoplasm | The neoplasm is of a specific cell type within a specific organ or tissue |

| Statistical association | |

| Genetic linkage |

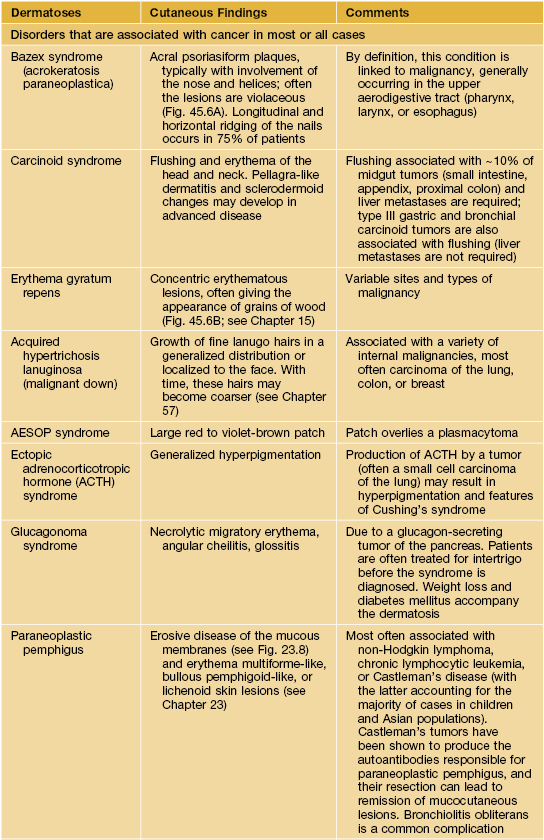

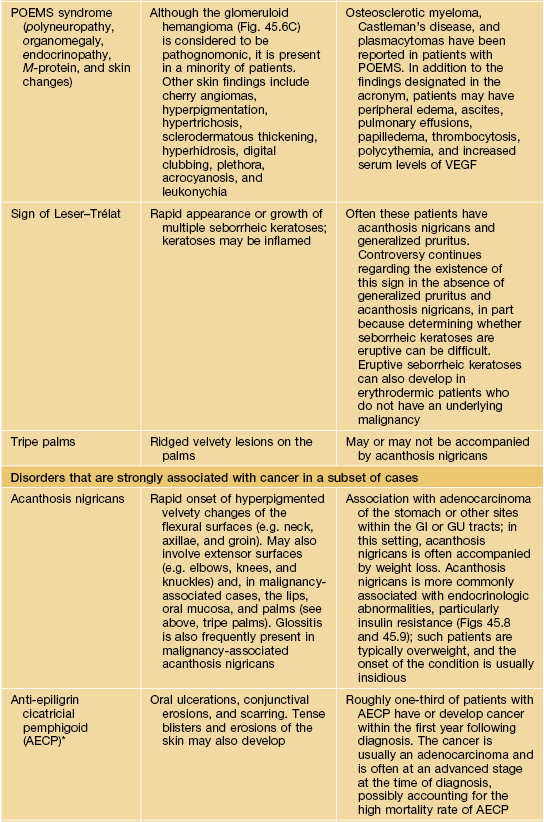

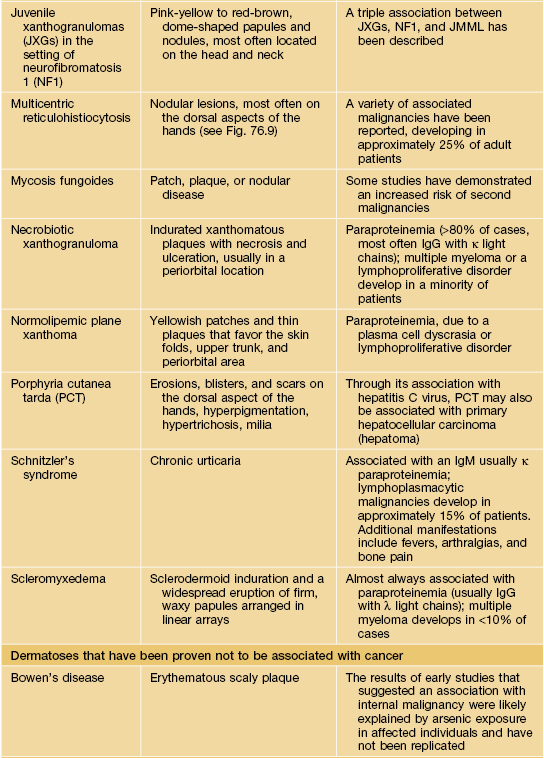

Table 45.9

Paraneoplastic dermatoses.

* Statistical association.

AESOP syndrome, adenopathy, extensive skin patch overlying (a) plasmacytoma; GI, gastrointestinal; GU, genitourinary; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; JMML, juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia.

Fig. 45.6 Skin signs that are associated with an internal malignancy in most or all cases. A Bazex syndrome (acrokeratosis paraneoplastica). The patient had an SCC of the tonsillar pillar. B Erythema gyratum repens. This patient had cancer of the breast. C POEMS syndrome. Note the multiple angiomas (glomeruloid hemangiomas histologically) on the trunk. In addition, he had peripheral neuropathy, hypothyroidism, and peripheral edema. His underlying disorder was an osteosclerotic myeloma. Courtesy, Jeffrey P. Callen, MD.

Skin Signs of Endocrine Disorders and Metabolic Disease

• Tables 45.10–45.14 and Figs. 45.8–45.12.

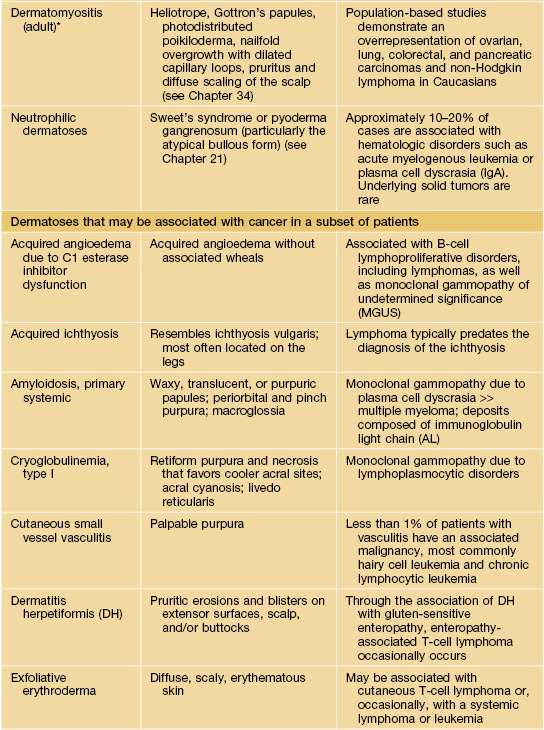

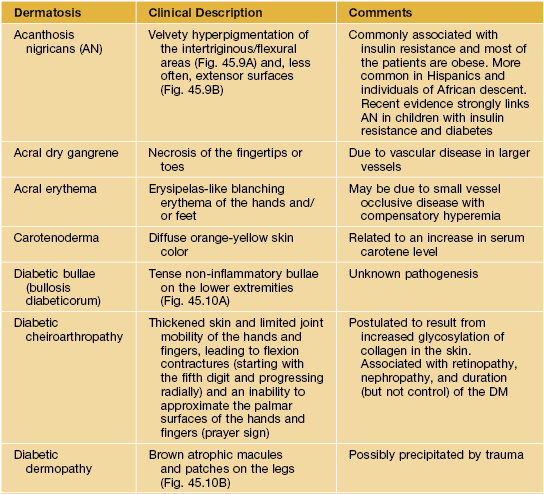

Table 45.10

Selected dermatologic associations of diabetes mellitus (DM).

Additional cutaneous conditions associated with DM include hirsutism (e.g. related to polycystic ovary syndrome or HAIR-AN – hyperandrogenemia, insulin resistance, acanthosis nigricans; see Chapter 57), necrolytic migratory erythema (in the setting of DM due to a glucagon-secreting pancreatic tumor; see Table 45.9), and infections such as mucocutaneous candidiasis, erythrasma (especially the disciform variant), cellulitis, and necrotizing fasciitis.

Adapted from Jorizzo JL, Callen JP. Dermatologic manifestations of internal disease. In: Arndt KA, Robinson JK, LeBoit PE, et al. (eds) Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1996:1863–1889.

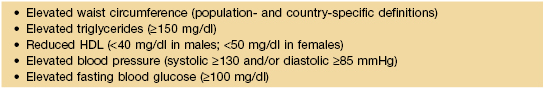

Table 45.11

Criteria for the diagnosis of the metabolic syndrome.

Metabolic syndrome is identified by the presence of three of these five criteria. Drug treatment for dyslipidemia, hypertension, or hyperglycemia also fulfills the corresponding criterion. Most patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus meet criteria for metabolic syndrome.

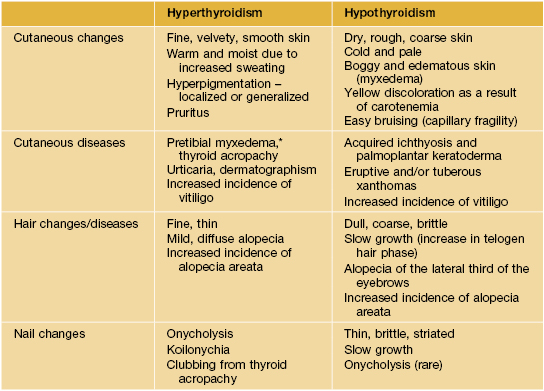

Table 45.12

Dermatologic manifestations of thyroid disease.

A serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level is the most reliable test of thyroid function, and it is usually markedly suppressed in patients with hyperthyroidism. Additional laboratory findings in hyperthyroid patients include elevated free T3 and/or free T4 levels. Patients with primary hypothyroidism have elevated TSH levels and decreased free T4 levels. The detection of anti-thyroid peroxidase and/or anti-thyroglobulin antibodies points to autoimmune thyroid disease (Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, Graves’ disease), whereas the presence of anti-TSH receptor antibodies points to Graves’ disease. Ascher’s syndrome consists of blepharochalasis, double lip, and goiter.

* Can persist when patient is treated and becomes euthyroid or can be associated with euthyroid Graves’ disease.

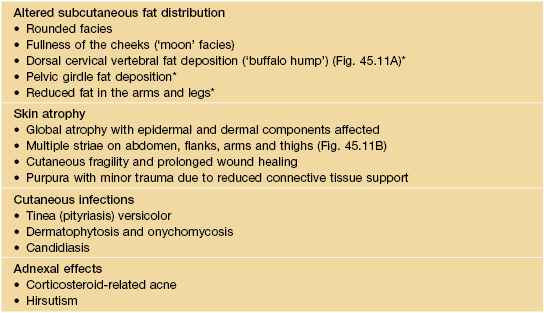

Table 45.13

Dermatologic manifestations of Cushing’s syndrome.

An overnight dexamethasone suppression test (8 a.m. plasma cortisol >140 nmol/l after receiving 1 mg at midnight) or 24-hour urine free cortisol determination (>140 nmol/24 h) can be used as a screen for Cushing’s syndrome due to endogenous cortisol production. Elevated plasma adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) levels are found in Cushing’s disease (pituitary overproduction of ACTH) and ectopic ACTH syndrome, whereas ACTH levels are suppressed in patients with adrenal tumors.

* This same change is indicative of insulin resistance and occurs in HIV-associated lipodystrophy.

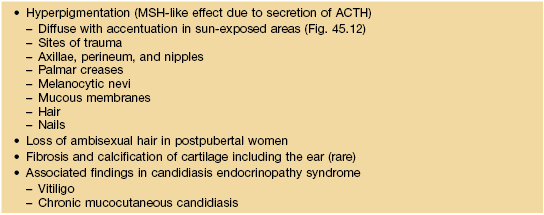

Table 45.14

Selected dermatologic manifestations of Addison’s disease.

The rapid adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) stimulation test (which assesses adrenal reserve) should be performed when adrenal insufficiency is suspected, because basal serum cortisol levels may be normal in patients with partial deficiencies. Plasma ACTH levels are elevated in primary adrenocortical insufficiency (Addison’s disease) and suppressed in secondary adrenocortical insufficiency (e.g. due to exogenous glucocorticoid therapy).

MSH, melanocyte stimulating hormone.

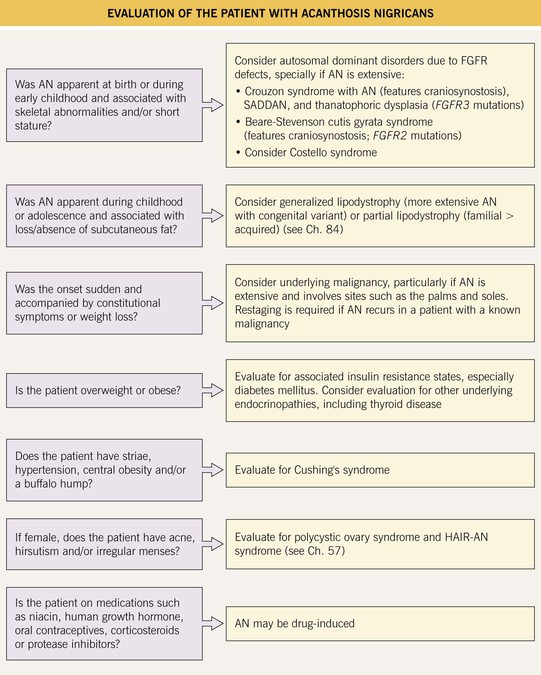

Fig. 45.8 Evaluation of the patient with acanthosis nigricans (AN). FGFR, fibroblast growth factor receptor; HAIR-AN, hyperandrogenemia, insulin resistance, acanthosis nigricans; SADDAN, severe achondrodysplasia with developmental delay and AN.

Fig. 45.9 Acanthosis nigricans (AN). A AN and acrochordons of the neck in the setting of insulin resistance and obesity. Note the velvety texture of the skin. B AN over the knuckles. AN can involve extensor surfaces as well as flexural areas. A, Courtesy Jeffrey P. Callen; B, Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD.

Fig. 45.10 Skin signs of diabetes mellitus. A Bullosis diabeticorum (diabetic bullae) with non-inflammatory bullae on the lower extremity. B Diabetic dermopathy characterized by brown macules and patches on the shins. C Eruptive xanthomas are frequently associated with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus. This patient was first discovered to have diabetes following the appearance of these yellow-red papules. D Necrobiosis lipoidica. Controversy exists about the exact risk of diabetes mellitus in such patients, but it is more strongly associated with diabetes than is granuloma annulare. E Neuropathic ulcers on the toes of a patient with diabetic sensory neuropathy. A, C–E, Courtesy, Jeffrey P. Callen, MD; B, Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD.

Fig. 45.11 Skin signs of Cushing’s disease. A ‘Buffalo hump’ of Cushing’s syndrome due to fat redistribution. The patient also has evidence of hirsutism. B Cushing’s syndrome with multiple striae. Courtesy, Judit Stenn, MD.

For further information see Ch. 53. From Dermatology, Third Edition.