Chapter 185 Skin and Wound Care

A multidisciplinary approach to skin care can effectively minimize the unnecessary morbidity and mortality secondary to pressure ulcers (PUs). In addition to contributing to patient morbidity and negatively affecting quality of life, PUs also result in considerable expense. It has been reported that 1.6 million PUs develop in U.S. hospitals every year. The total cost to treat PUs has been estimated to be between $2.2 billion and $3.6 billion annually. In 2006, adult hospital stays noting a diagnosis of PUs totaled $11 billion.1 Approximately $125 to $200 is spent for each stage I and stage II PU that develops, and $14,000 to $23,000 is spent for each stage III and stage IV PU. Seventy-five percent of acute care acquired ulcers occur in patients who have undergone a surgical procedure that lasted 3 hours or longer. This same group accounts for 30% to 40% of the total cost associated with PUs.2 Hospitalizations involving patients with PUs developed either before or after admission increased by nearly 80% between 1993 and 2006. 1

It has been estimated that 25% of the medical costs associated with spinal cord injuries (SCIs) are incurred as a result of PUs. Overall, the average cost of treating a single PU can range from $5000 to $50,0003,4; 1 to 6 months of additional hospital stay is often required. Infectious complications of PUs, such as cellulitis, osteomyelitis, sepsis, and endocarditis, account for more than 60,000 deaths annually.5–7

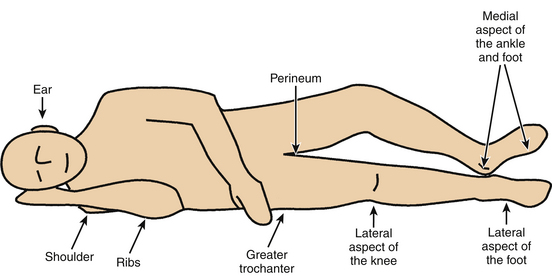

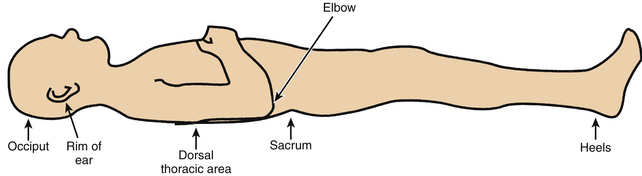

A PU (also known as a pressure sore, decubitus ulcer, or bedsore) is an area of damaged skin and underlying soft tissues resulting from prolonged unrelieved pressure between a bony prominence and an external surface. In a patient, pressure ulcer injury can occur over the scapula, occiput, sacrum, and heels when placed in the supine position; the ear, shoulder, greater trochanter, medial knee, malleolus, and foot edge when laterally positioned; and the nose, forehead, chest, iliac crests, foot edge, and toes when placed in the prone position.8

Incidence and Prevalence

The incidence of PUs occurring in postoperative patients varies from 12% to 45%9; others report an incidence of 12% to 66%.9,10,11 In one study the prevalence of ulcer development within 4 days of surgery, by stage, ranged from 0.65% (unstageable) to 6.44% (stage I). The total number of intraoperatively acquired PUs is 23% of the total number of ulcers developed in hospitals.2

PUs occur in 28% of SCI patients. According to the National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center, the incidence of PUs during the initial hospital stay is 32%.12 Another study reported a PU rate of 30% to 85% during the first month after injury.13–19 In a retrospective study of SCI the PU rate was found to be 60% and 50% in quadriplegic and paraplegic patients, respectively; also, multiple PUs developed in most quadriplegic patients.20–24

Etiology

Historically, PUs have been blamed on poor nursing care and have been used as outcome indicators to quantify good versus poor nursing care.11,25 In fact, PUs are acute injuries that develop rapidly when compression of tissues causes ischemia and necrosis during serious illness and trauma, including surgery.26 The primary factor contributing to PU formation is constant pressure for extended periods. Pressure induces ischemia and causes reactive hyperemia. Because muscles and subcutaneous tissues are more susceptible than epidermis to pressure-induced injury, PUs are usually worse than they initially appear. The visible portion of a PU is not truly indicative of the extent of the problem.27

The mean skin capillary pressure in healthy persons is approximately 25 mm Hg.28 External compression with a pressure of more than 30 mm Hg occludes the blood vessels, so that the surrounding tissue becomes anoxic and cell death occurs. Tissue pressure, however, depends on the patient’s health. In addition, the amount of tissue damage is proportional to the magnitude and length of application of the pressure. PUs can develop within 24 hours of the insult but can take as long as 5 days to manifest themselves.27 Kosiak28 demonstrated that applying a constant pressure of 70 mm Hg to the skin caused irreversible changes in less than 2 hours. He also demonstrated an inverse relationship between time and pressure. Intense pressure for short periods was tolerated by patients as well as low pressure for long periods of time without sustaining tissue injury. Even a brief period of pressure relief can reduce the likelihood of PUs.

Risk Factors and Their Assessments

Most hospitals use a standardized risk assessment tool to predict the likelihood of an individual developing a PU. An individual prevention plan will be created and implemented based on the patient’s risk assessment/score. Several tools for risk assessment of PU prevention are available. The most commonly used validated and reliable tool for predicting patients at risk for pressure ulcer development is the Braden Scale for Predicting Pressure Sore Risk. Full risk assessment includes determining a person’s risk for pressure ulcer development and inspection of skin condition, particularly of pressure points.29 Recommendations for culturally sensitive early assessment for stage I pressure ulcers in patients with darkly pigmented skin include the use of a halogen light to look for skin color changes, which may occur in blue hues, and to compare skin over bony prominences to surrounding skin, which may be boggy or stiff, warm or cooler.30

Intrinsic Risk Factors

Age

Several changes that occur in normal skin with aging may predispose older persons to PU development. These factors include decreased epidermal turnover, flattening of the dermoepidermal junction, and decreased number of dermal blood vessels. Bridel31 reported gradual reduction in collagen formation between ages 20 and 60. A marked drop in collagen synthesis with concurrent loss of its protective mechanism occurs after age 60. In general, the risk of PU development doubles after age 40 and triples after age 70.

Pattern of Spinal Cord Injury

Each year 25% of SCI patients will develop a PU. Regardless of the type of treatment of these PUs, they will recur in 5% to 91% of SCI patients.27 The pattern of SCI (completeness of neurologic deficit, level of injury [quadriplegia vs. paraplegia], and muscle tone [spastic vs. flaccid]) can affect skin care and PU formation. Richardson and Meyer18 examined variables related to PU formation in acutely injured SCI patients and found that quadriplegic patients with complete injuries were more likely to develop PUs than were those with lower level or incomplete injuries. However, Curry and Casady14 reported that cervical injuries were not associated with an increased rate of PU formation. They reported PUs in 22.2% and 28.5% of patients with cervical and thoracolumbar injuries, respectively. Spasticity can contribute to PU development. Shearing forces in SCI are increased threefold, partly as a result of lower limb spasticity.

Immobility

Immobility has been found to be the most significant risk factor for PU development.32 Immobility may be caused by mental status changes, physical deficit, or neurologic deficit, or may occur during surgery.

Malnutrition

Increased PU risk occurs in malnourished patients by the reduction of tissue tolerance.33 Integrity of the skin and support structures is influenced by nutritional status. Low serum albumin levels have been shown to predict injury from pressure.12 Collagen and elastin can diminish the ability of soft tissue to absorb pressure. Lack of vitamins and trace elements necessary for collagen formation and cell metabolism can predispose the patient to increased risk of pressure damage.34

Decreased fluid intake in the malnourished patient can lead to increased risk for dehydration. Dehydration can affect tissue perfusion, resulting in reduced pliability and dry, flaky, or scaling skin associated with fissuring and cracking of the stratum corneum. This ultimately places the patient at an increased risk for PU formation.27

Body Weight

The emaciated patient has little padding over bony prominences and is vulnerable to pressure injury. The obese patient may be malnourished with poor tissue perfusion and may be difficult to move while avoiding shearing and frictional forces. Patients are at risk of pressure damage if they are less than 90%, or more than 120%, of their ideal body weight.9

Cardiovascular Changes

Some cardiovascular changes secondary to SCI can diminish tolerance to pressure and pressure-induced ischemia. The loss of sympathetic innervation and unopposed parasympathetic activity contribute to vascular stasis and tissue hypoxia in SCI patients. The loss of vasomotor tone produces vasodilation, bradycardia, and an increased cardiac index. This results in an increased stroke volume and a decreased venous return. The reduction in venous return is further accentuated by decreased muscle tone and the absence of the muscle pump. Gravity, acting mainly when the patient is in the sitting position, and a decreased negative inspiratory force, resulting from pulmonary insufficiency, may also diminish venous return. In the SCI patient, soft tissue blood flow below the level of injury is reduced to 33% of its normal value. A decrease in transcutaneous oxygen tension is observed in the SCI patient, even in the absence of pressure.17 All of these factors contribute to the formation of PUs. In summary, poor tissue oxygenation, poor cell nutrition, and a decrease in venous return may accentuate the process of PU formation.

Extrinsic Risk Factors

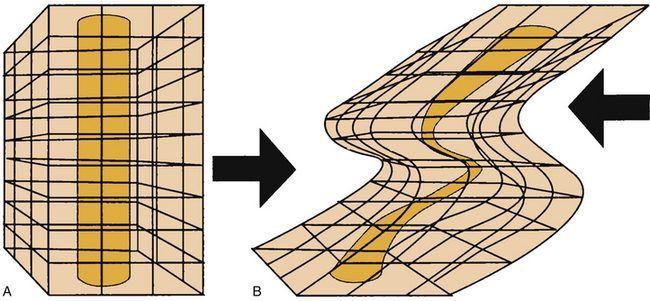

Shearing

Shear forces are the second key factor in the development of PUs. Shear forces are defined as forces created by sliding adjacent structures, which cause a relative displacement of tissue and, in turn, occlusion of capillaries. Shear forces can be more significant than pressure itself in the dermis (where capillaries run perpendicular to the skin) and near the bone (where nutrient vessels pierce the fascia, also in a perpendicular manner) (Fig. 185-1). Shear forces, alone or in combination with pressure, significantly compromise circulation in tissues, whereas the skin may remain stationary. The elevation of the head of the bed by more than 30 degrees may increase shear forces.

Moisture

Contact of skin with moisture, resulting from urinary or fecal incontinence, leads to skin maceration and edema. This makes the epidermis more susceptible to abrasion. The likelihood of further tissue breakdown thus increases. The effect of moisture on PU formation is well known. One study demonstrated that incontinence caused a 5.5-fold increase in the incidence of PUs.35 Fecal incontinence is a greater risk factor for PU development than urinary incontinence, because stool contains bacteria and enzymes that are caustic to the skin.11,27

Surgery

Preoperative factors that place patients at risk for PUs include the following comorbidities: diabetes, underlying respiratory disease, hypertension, and vascular disease. Low preoperative hemoglobin and hematocrit, as well as a preoperative serum albumin level lower than 3 g/dL, also have been shown to place patients at greater risk for PU.12,36,37

Surgical patients are at an increased risk because of forced immobility during surgery.12 The amount of time on the operating room (OR) table is the most statistically significant risk factor associated with PU injury in perisurgical patients.9 Studies have shown variable amounts of time before PU injury occurs. Hoshowsky and Schramm38 found that PU injury can occur in as little as 2.5 hours on the OR table. Surgery lasting more than 4 hours can triple the risk of skin changes and quadruple the risk of PU formation. Hicks39 found that PU injury was twice as likely to occur if time on the OR table was more than 4 hours.

Not only does the amount of time on the OR table contribute to PU formation, but anesthetic agents lower blood pressure and alter tissue perfusion, which also contributes to tissue damage.40 Surgical patients’ skin may be made more susceptible to PUs because of pooled prep solution, causing skin maceration, change in skin pH, and the removal of protective oils.9,11 In addition, one study showed that 75% of patients placed on a hyperthermia blanket during surgery went on to develop PUs.9,10,41

Firm positioning devices in the OR are used to hold patients in place by exerting pressure on bony prominences, retractors increase pressure on internal tissues, and OR personnel increase pressure on external tissues by leaning on the patient.11 All of these events can cause pressure over bony prominences, eventually leading to PU injury.

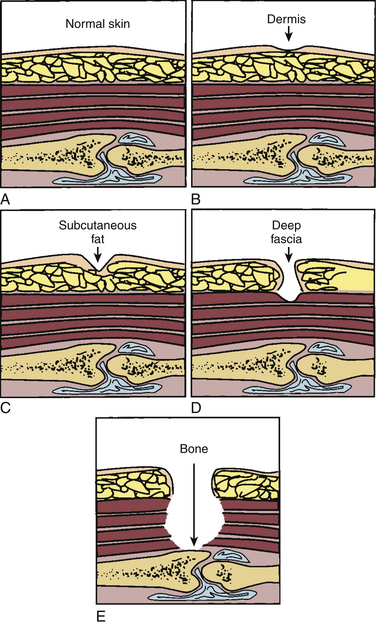

Assessment and Staging of Pressure Sores

Routine skin inspection is customarily included in any skin care program because it provides important information regarding the formulation and evaluation of skin care plans. At least once daily the skin should be examined from head to toe, and high-risk areas should be assessed more frequently, with special attention paid to bony prominences. Assessment involves the entire integument, not just the ulcer, and is the basis for a treatment plan and its evaluation. PU assessment should include location, size (length, width, and depth), the extent of sinus tract undermining or tunneling, exudate, color of wound bed, epithelialization, and staging.11 Photographs can document PU status better than hand-drawn diagrams.

Although several different staging and classification systems have been developed for PU classification, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) (formerly the Agency for Healthcare Policy and Research) has adopted the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel’s PU classification system as part of the PU clinical practice guidelines. PUs are staged to classify the degree of observed tissue damage. The use of this classification tool permits universal assessment and consistent communication of the severity of tissue damage among health care personnel (Fig. 185-2).19,36

Skin inspection should be followed by laboratory investigations, such as culture and assessment for infection markers. In the case of a chronic nonhealing PU and underlying osteomyelitis, a triad of a white blood cell count higher than 15,000/μL, plain radiographic signs, and a high sedimentation rate (>100 mm/hr) provides a sensitivity and specificity of 90% for diagnostic screening of this complication.4

Prevention

The foundation for the prevention of PUs is based on the elimination of risk factors. The first step in PU prevention is to be knowledgeable of risk factors, specifically which ones place the patient at high risk for PU development. The second step in prevention is to be aware of the interventions that reduce the risk of pressure injury. The third step is to evaluate the effectiveness of the intervention.27 Proper measures can minimize the PU rate by as much as 59%.4,23,42–44 Prevention is a 24-hour, ongoing process. Management of PU risk includes an understanding of body positioning, turning, and mobilization of the patient in the bed and wheelchair. It also includes paying attention to hygiene and the use of pressure reduction devices and strategies, as well as the appropriate monitoring of nutritional and hydration status.

Mobilization and Turning Program

At-risk patients should be turned every 2 hours to minimize pressure on bony prominences.15,45,46 A written schedule for systematically turning and repositioning the patient should be used. Norton et al. reported a lower incidence of PUs in at-risk patients who were turned every 2 to 3 hours.47

The goal of repositioning is to facilitate tissue reperfusion before the tissue becomes ischemic. Repositioning should involve a sustained relief of pressure. As skin tolerance improves, the amount of time spent in one position may be increased gradually.

After the acute phase of care, when the SCI patient is able to tolerate wheelchair activities, continuation of pressure relief techniques in the wheelchair is equally important. These activities serve to relieve pressure and maintain (and increase) the strength in the upper extremities. Wheelchair pushups, lateral weight shifts to each side, and forward over-the-knees positioning are some of the effective pressure relief techniques used.48

Improper transport of the patient increases the incidence of PUs. When transferring patients, care should be taken to not slide or drag the skin across the bed surface.49 The patient may also help prevent friction injuries by taking an active role and using the trapeze during turning and repositioning (if the spine is stable).

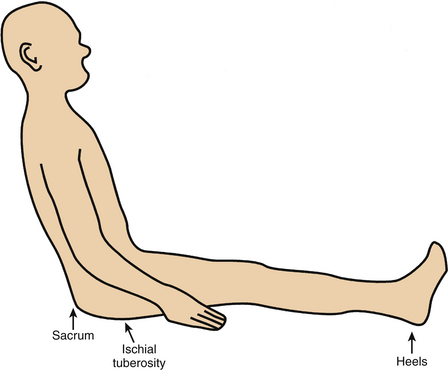

Ischial PUs are a manifestation of prolonged sitting without focal pressure reduction. Appropriate care, patient education, and patient diligence should minimize incidence of this complication (Fig. 185-3). Sacral PUs also may be caused by sitting, particularly if an inappropriate or worn-out chair is used or if the patient sits with the pelvis excessively flexed.

Uninterrupted sitting in a chair or wheelchair is a common cause of PU. When in a wheelchair, SCI patients should reposition themselves at least once every hour and shift their weight every 15 minutes. If the patient needs assistance, simply standing the patient and reseating in the chair may minimize the risk of tissue injury. Small shifts in weight such as elevating the legs can help to reduce the risk of tissue injury.27

General Hygiene

Proper patient hygiene can help to prevent or at least minimize the likelihood of PUs. Bathing programs should include washing with mild soap and water to avoid excessive skin drying and cracking. The skin should be kept clean and free of moisture from urinary and fecal incontinence, perspiration, and wound drainage. However, it is important to keep the skin well lubricated with a simple standard hospital skin moisturizer. Studies have shown that petrolatum is more effective than lanolin on dry skin.50

Nutrition

Proper nutrition is an important factor in maintaining the vitality of intact tissues. Nutritional needs are based on the patient’s age, gender, body mass index, anorexia or obesity, current disease state, severity of illness, and presence and severity of wounds. A through nutritional assessment is an important component of the initial evaluation of a patient with a PU.51

A high-protein diet, with an increased caloric intake, is initially needed to replace weight loss and to prevent protein deficiency and anemia. If necessary consult a dietitian and correct nutritional deficiencies. Monitor and order vitamins A, C, and E supplementation as needed.30 Normal albumin is 3.5 to 5.5 g/dL and prealbumin is 15 to 25 mg/dL.51

Adequate fluid intake is 30 to 35 mL/kg of body weight. Patients on air-fluidized beds for the prevention of PUs must have their fluid intake increased an additional 10 to 15 mL/kg of body weight to prevent dehydration.52

The nutritional state of the patient is also affected by drugs, alcohol, nicotine, and caffeine. Nicotine and caffeine are vasoconstrictive, leading to a decrease in tissue oxygenation that, in turn, affects tissue healing. Smokers have a higher rate of extensive PUs than do nonsmokers.44,53–55

Patient Support Surfaces

Beds

In general, studies comparing several specialized beds show no statistical significance in the prevention or healing of PUs from one bed to another. However, studies do show that PUs heal more quickly on specialized beds when compared to foam overlays or standard hospital mattresses.56

Air-fluidized Beds

An air-fluidized bed is an oval space with up to 2000 pounds of glass beads covered by a polyester sheet. The beads are fluidized by a flow of warm, pressurized air that floats the polyester cover on which the patient is placed. Feces and body fluids are able to flow through the polyester sheet; thus the skin is kept dry. Most studies have demonstrated a rapid rate of wound healing using these beds, compared with conventional treatment.5,43,57,58 These beds have a bactericidal effect because of sequestration and desiccation of micro-organisms by the ceramic beads. Adverse effects include fluid loss, dehydration, dry skin, scaly skin, and epistaxis from the flow of the dry air. Turning and repositioning may be difficult.

Low-Air-Loss Beds

Low-air-loss beds consist of multiple inflatable fabric pillows that are attached to a modified hospital bed frame. An electric fan maintains the buoyancy of the pillows. The head and foot of the bed can be elevated. They are cooler and more portable than air-fluidized beds; however, urine and feces cannot pass through the fabric. Their use has been found to be associated with a threefold increase in tissue healing.43

Patient Positioning

Perhaps the most important anatomic and soft tissue bony prominences in the bedridden patient are the sacrum and the heels.59 The importance of these pressure points is diminished when the patient assumes positions other than the supine position.

The sacrum is located superficially at its dorsal aspect, with very little soft tissue separating the bone from the integument. When the supine position is assumed, significant pressure is applied to this point. Although the sacrum is a common site for PU formation related to supine positioning, the scapula and occiput are also potential points of pressure (Fig. 185-4). Both regions have bony prominences with minimal overlying soft tissue. The prevention of sacral, scapular, and occipital PUs is predicated on limiting the time spent in the supine position.

FIGURE 185-4 The supine position can lead to pressure application predominantly on sacrum, scapula, heels, and occiput.

Evidence suggests that when the side-lying position is used, pressure on the greater trochanter should be minimized; the patient should be placed at a 30-degree laterally inclined angle rather than a 90-degree angle to avoid direct pressure on the greater trochanter.11 Placing a patient in a position that is intermediate between the full lateral decubitus and the supine position perhaps applies significant pressure to the downside scapula while lessening pressure on the sacrum. Dorsolateral buttock pressure is also increased. This, however, is usually tolerated well because of the significant soft tissue mass overlying this region. This position, for the reasons listed, is a reasonable alternative intermittent position. No single position should be maintained for any significant length of time, however. The full lateral decubitus position exposes the downside greater trochanteric region to significant focal pressure, if proper technique is not used. The anatomic arrangement of the greater trochanter and surrounding soft tissues is of great importance in this regard. One must keep in mind the dynamic relationship between the overlying soft tissues and the bony prominence (greater trochanter).11

In the hip-flexed position the greater trochanter is more superficial (exposed) relative to the immediately overlying soft tissue surrounding the trochanter itself. The latter is composed of the gluteus maximus and the lateral thigh muscles. When the hip is extended (leg straightened), the greater trochanter retracts relative to the surrounding soft tissue. This extended position results in a distribution of pressure over a significantly wider surface area, thereby minimizing focal trochanteric pressure (Fig. 185-5). It would therefore seem prudent to straighten the downside leg in the full lateral decubitus position. This essentially eliminates the negative effects of the lateral decubitus position (Fig. 185-6).11

Heels are at an increased risk of PU development because they have higher tissue interface pressures than other tissues covering bony prominences. Heels must be elevated off the bed surface by some protective mechanism. A common practice is to use pillows under the calves to prevent heels from bearing pressure loads, which prevents them from resting on the surface of the bed.27

Treatment of Pressure Sores

When a PU occurs it can be treated either medically or surgically, depending on the chronicity, position, and size. When developing a plan of care for treatment, the treatment goal must first be determined. The care will be healing, palliative, or maintenance; the treatment goal will help to determine the plan of care.51

Knowledge of comorbidities and chronic conditions and how they affect the healing process by reducing available oxygen, amino acids, vitamins, and minerals at the wound site determines the appropriate interventions for optimal PU healing.51 Many of the components used in prevention of PUs are also used in their treatment, but at a more intense level of management. The extrinsic and intrinsic contributing factors of PU formation must be identified. Eliminating the cause of pressure should improve the course of treatment.

With respect to wound care, the goal is to achieve a clean wound with a low level of bacteria that is kept moist with a nonadherent dressing until complete wound healing has occurred.11

Systemic Therapy

In some circumstances, oral antibiotics and vitamin C may be indicated. Vitamin C has been found to help in chronic nonhealing PUs.60

With osteomyelitis, cellulitis, and sepsis, and also as prophylaxis for endocarditis, systemic antibiotic therapy may be indicated.61 Sepsis secondary to PU infections is associated with 50% mortality in the hospital setting (Fig. 185-7). Gentamicin and clindamycin are antibiotics of choice in patients with good renal function. In older patients cefotetan disodium or ticarcillin-clavulanic acid and fleroxacin are reasonable alternatives.4,62 First-generation cephalosporins do not penetrate PU wounds well and should not be used.

Topical Therapies

Wound Dressings

The main goal when using moist PU wound dressings is to keep the wound moist and the surrounding skin intact and dry.51 Traditional wound dressings are considered to be passive products because they protect the wound from further injury while healing occurs. However, many new wound dressings are interactive in that they act to alter the local wound environment. Regardless of the type of dressing selected, the main purpose is to absorb exudates, provide thermal insulation, allow gaseous exchange, protect the wound from infection, maintain a moist wound environment, and relieve pain. Interactive dressings have a varying number of properties and are currently undergoing research.27,63

Hydrocolloid

Hydrocolloids contain an adhesive material that physically interacts with wound fluid. These occlusive or semiocclusive dressings encourage wound cleaning and debridement through the process of autolysis. They promote the development of granulation tissue by stimulating angiogenesis. They may not adhere to highly exudative wounds. They can be used for stage II and stage III PUs.43,64 Currently, hydrocolloids are cost effective and require changing every 3 to 7 days.

Hydrogel

Hydrogels are three-dimensional hydrophilic polymers that interact with aqueous solutions by swelling and maintaining water in their structure. They are nonadhesive and conform to the wound surface. Hydrogels are very absorbent and dehydrate easily. They can be used in stage IV PUs.

Cleaning Agents

AHRQ guidelines recommend cleaning PUs at each dressing change. Techniques should be chosen that use the least amount of chemical and mechanical trauma necessary to clean the wound adequately. Traumatized wounds have a higher rate of infection and slower healing time.51 For some wounds isotonic saline irrigation is a sufficient cleanser. Extremely dirty wounds may need a stronger cleanser and more mechanical force. As the wound heals and becomes cleaner, less mechanical force and a gentler cleanser should be used.11,66

It has been shown that whirlpool therapy results in faster wound healing than standard treatment. Pulsatile irrigation and lavage of PUs has been shown to be more effective than whirlpool therapy, especially in the presence of slough and necrotic tissue.11,51

Normal saline solution is a safe and effective cleanser for all wounds because it is physiologic and will not harm tissue. New guidelines recommend against the use povidone-iodine, acetic acid, hydrogen peroxide, and sodium hypochlorite because they are cytotoxic and may impair wound healing by damaging granulation tissue.51 Some antimicrobial agents, such as mupirocin ointment and silver sulfadiazine, may decrease the bacterial count. In general, topically applied antibiotics do not penetrate deeply into the ulcer, and their use is not recommended. They can lead to a resistance to antibiotics, as well as cause hypersensitivity reactions, contact dermatitis, and drug toxicity from drug absorption.67 A 2007 Cochrane Review of wound cleaning for pressure ulcers determined that there is no good evidence that cleaning PUs or cleaning with a particular solution helps healing. Very little research has studied the cleaning of PUs; therefore, conclusions cannot be drawn.68

Negative Pressure Wound Therapy

Negative pressure wound therapy creates a controlled negative pressure in an attempt to provide evacuation of wound fluid, stimulate granulation tissue, decrease bacterial colonization, and enhance the body’s natural capacity to heal.51

Vacuum-assisted closure uses an open-celled foam that can be cut to the size of the PU and placed on top of or inside the PU. It is then secured with a transparent film. Negative pressure is applied to the wound by means of flexible tubing that is embedded in the foam and attached to a vacuum pump. Constant tension approximation uses a device to place tension traction on the wound margins.66 Although this is a new PU wound treatment, the literature is equivocal. Studies do not show that it is inferior to other treatments, and it may increase patient comfort and decrease nurse staff hours for fewer dressing changes.51 A patient must have an overall physiologic capacity of heal to be an appropriate candidate for negative pressure wound therapy.51 Currently, negative pressure therapy is recommended for patients with stage III or IV nonhealing PUs in whom other conventional treatments have failed. Contraindications for negative pressure dressings include necrotic tissue with eschar, untreated osteomyelitis, or malignancy in the wound. Precautions to consider include active bleeding, anticoagulation use, and difficult wound hemostasis.51

Adjunctive Therapies

Electrical Stimulation

Low-voltage direct current and high-voltage pulsed galvanic stimulation has been used successfully in treating PUs. During treatment, the negative electrode is placed directly on the wound and the positive electrode is placed at some point distally. In a randomized, double-blind, multicenter study, electrical stimulation has been shown to increase the rate of healing of PUs. The Pressure Ulcer Guideline Panel recommended the use of electrotherapy in stage III and stage IV PUs that have proven to be unresponsive to conventional therapy. Electrical stimulation may also be useful for recalcitrant stage II PUs.43,66,69

Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy is defined here as the use of high-pressure, pure, humidified oxygen applied by a portable chamber to either the entire body or to an extremity. The chamber forces 100% oxygen into superficial tissue and assists with wound healing. This modality has been found helpful in SCI patients, because they have an underlying intact arterial supply.44,70 However, the AHRQ does not recommend this therapy, because its effectiveness has not been established.66

Ultrasound

The use of ultrasound for healing of PUs has produced equivocal results, with some studies demonstrating efficacy but more series finding it ineffective.27,71

Laser

Laser therapy has been used effectively in animal models for the treatment of PUs. Studies have demonstrated healing of PUs using the helium-neon laser in one third of cases, compared with nonlaser-treated wounds.44 Research on the use of lasers for human PUs is still in the early stages.

Growth Factors

Growth factors are naturally occurring proteins secreted from platelets and macrophages that direct the migration of cells into wounds and lead to the process of repair. In current experimental studies topically applied, platelet-derived growth factors and fibroblast growth factors have been used to promote healing of chronic PUs. Preliminary data suggest improved wound healing.24,72 Other growth factors, such as TGF-beta and epidermal growth factor, have been identified as potential therapies.73 Although these modalities hold promise, they are still investigational and consequently are not yet recommended for routine use.

Normothermia

Normothermia therapy is used to encourage local blood flow and oxygen to the wound. A foam collar is placed around the wound, and a transparent film is attached to the collar and placed over the wound. A warming device controlled by a temperature control unit is placed into a pocket on the transparent film, and the environment underneath the film cover is kept at 38°C. Initial studies are showing positive results.66

Debridement

Debridement, the removal of necrotic tissue, is fundamental to the healing of a PU. Wounds must be clean for healing to take place. The goal of PU wound debridement is to accelerate wound healing, decrease the risk of infection, and prevent further complications by reducing tissue destruction.51 The removal of inflammatory stimuli, such as devitalized tissue, reactive chemicals, and bacteria, requires debridement and cleaning.11 Large numbers of bacteria normally reside in necrotic tissue. The presence of necrotic material dictates local debridement to decrease the bacterial cell count to 100,000 per gram of tissue. Eschar is the collection of dead tissue within the wound; slough is the stringy, devitalized tissue that adheres to the wound bed.51 The different methods of debridement may be combined to achieve the best result.

Mechanical Debridement

The most commonly used method of mechanical debridement is the wet-to-dry dressing technique. It has been shown that woven gauze with larger pores and coarser weave, compared to nonwoven cotton sponges, is more effective for debridement.74 This is most effective when used on PUs with necrotic tissue in stages II, III, and IV. The wet-to-dry technique is painful and should be discontinued when the wound bed looks pink.27

Chemical Debridement

Autolytic debridement is less painful. When the wound is kept moist with an occlusive dressing, the wound uses its own enzymes to digest the nonviable tissue and viscous exudates.27 To enhance autolysis, exogenous enzymes may be applied to the wound. Enzymatic preparations may be fibrinolytic or collagenolytic and can cause the liquefaction of necrotic tissue and facilitate its removal by sharp or mechanical debridement. As far as possible, eschars should be removed from the wound; the remaining devitalized tissue should be scored with a scalpel before enzymatic debridement.11 Enzymatic preparations are used in the treatment of stages II, III, and IV PUs. Although they are not able to debride hard eschars, these preparations can loosen them.

Biologic Debridement

Biologic debridement using maggots has been recognized for centuries as an aid to wound healing. Maggots liquefy necrotic tissue but not healthy tissue. They disinfect the wound and stimulate tissue growth. Sheman et al.75 reported that maggot therapy debrided most of the necrotic wounds within 1 week, which was more rapid than all other nonsurgical methods. They found maggot therapy to be beneficial, safe, and inexpensive.

Complications

All stage I PUs should heal rapidly. If a PU does not heal or respond to appropriate therapy, the possibility of infection should be considered. Associated infectious processes include chronic local infection, cellulitis, osteomyelitis, sepsis, and death. Chronic and nonhealing PUs occasionally show neoplastic changes.9

One of the causes of fever in SCI patients is localized soft tissue infection. The infected sore can progress and lead to osteomyelitis or sepsis. Beneath the infection site one may occasionally observe an abscess. Figure 185-7 depicts an unhealed and infected PU.

The management of PUs is complex and should be targeted toward prevention. The best, most cost-effective, and easiest treatment is prevention. Prevention necessitates education of both the patient and the treating team. Treatment of sores of the integument, “the largest organ of the body,” is aided by a team approach.

ICSI. Pressure ulcer treatment: health care protocol. Bloomington, MN: Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement; January 2008.

ICSI. Skin safety protocol: risk assessment and prevention of pressure ulcers: health care protocol. Bloomington, MN: Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement; March 2007.

Moore Z.E., Cowman S. Wound cleansing for pressure ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;4:CD004983.

30. Preventing pressure ulcers and skin tears. In: Capezuti E., Zwicker D., Mezey M., Fulmer T., editors. Evidenced-based geriatric nursing protocols for best practice. ed 3. New York: Springer; 2008:403-429.

Russo C.A., Steiner C., Spector W. Hospitalizations related to pressure ulcers, 2006,. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; December 2008. HCUP Statistical Brief #64Available at hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb64.pdf

1. Russo C.A., Steiner C., Spector W. Hospitalizations related to pressure ulcers, 2006,. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; December 2008. HCUP Statistical Brief #64Available at hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb64.pdf

2. Beckrich K., Aronovich S.A. Hospital acquired pressure ulcers: a comparison of costs in medical vs. surgical patients. Nurs Econ. 1999;17:263-271.

3. Langemo D. Incidence and prediction of pressure ulcers in five patient care settings. Decubitus. 1991;4:25-33.

4. Perez E.D. Pressure ulcers: updated guidelines for treatment and prevention. Geriatrics. 1993;48:39-44.

5. Allmann R.M., Laprade C.A., Noel L.B., et al. Pressure sores among hospitalized patients. Ann Intern Med. 1986;105:337-342.

6. Vidal J., Sarrias M. An analysis of the diverse factors concerned with the development of pressure sores in spinal cord injured patients. Paraplegia. 1991;29:261-267.

7. Yarkony G.M. Pressure ulcers: a review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1994;75:908-917.

8. Mayrovitz H.N. Pressure and blood flow linkages and impacts on pressure ulcer development. Atlanta: Paper presented at First Annual OR-Acquired Pressure Ulcer Symposium; March 1998.

9. Scott S.M., Mayhew P.A., Harris E.A. Pressure ulcer development in the operating room: nursing implications. AORN J. 1992;56:242-250.

10. Kemp M.G. Factors that contribute to pressure sores in surgical patients. Res Nurs Health. 1990;13:293-301.

11. Reuler J.B., Cooney T.G. The pressure sore: pathophysiology and principles of management. Ann Intern Med. 1981;94:661-666.

12. Lewicki L.J., Mion L., Splane K.G., et al. Patient risk factors for pressure ulcer during cardiac surgery. AORN J. 1997;65:933-942.

13. Bliss M.R. Acute pressure area care. Lancet. 1992;339:221-223.

14. Curry K., Casady L. The relationship between extended periods of immobility and decubitus ulcer formation in the acutely spinal cord-injured individuals. J Neurosci Nurs. 1992;24:185-189.

15. Linares H.A., Mawson A.R., Suarez E., Biundo J.J. Association between pressure sores and immobilization in the immediate post-injury period. Orthopaedics. 1987;10:571-573.

16. Mawson A.R., Biundo J.J.Jr., et al. Risk factors for early occurring pressure ulcers following spinal cord injury. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1988;67:123-127.

17. Mawson A.R., Siddiqui F.H., Biundo J.J.Jr. Enhancing host resistance to pressure ulcers: a new approach to prevention. Prev Med. 1993;22:433-450.

18. Richardson R.R., Meyer P.R. Prevalence and incidence of pressure sores in acute spinal cord injuries. Paraplegia. 1981;19:235-247.

19. Treatment of pressure ulcers, Clinical Guideline No. 15, AHCPR Pub. December 1994:95-0652.

20. Colen S.R. Pressure sores. In: McCarthy J.G., May J.W., Littler J.W., editors. Plastic surgery. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1990:3797-3838.

21. Leigh I.H., Bennet G. Pressure ulcers: prevalence, etiology, and treatment modalities. A review. Am J Surg. 1994;167:25S-30S.

22. Pope R. Pressure sore formation in the operating theatre: 1. Br J Nurs. 1999;8:211-214. 216–217

23. Singh R.V.P., Suys S., Villanueva P.A. Prevention and treatment of medical complications. In: Benzel E.C., Tator C.H., editors. Contemporary Management of spinal cord injury. Park Ridge, IL: American Association of Neurological Surgeons; 1995:195-215.

24. Wharton G.W., Milani J.C., Dean L.C. Pressure sore profile: cost and management. Paraplegia. 1988;26:124.

25. Dealy C. Pressure sores: the result of bad nursing? Br J Nurs. 1992;1:748.

26. Bader D.L., editor. Pressure sores: clinical practice and scientific approach. Basingstoke, UK: Macmillan, 1990.

27. Ratliff C.R. Pressure ulcer assessment and management. Lippincotts Prim Care Pract. 1999;3:242-258.

28. Kosiak M. Etiology and pathology of decubitus ulcers. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1959;40:62-68.

29. ICSI. Skin safety protocol: risk assessment and prevention of pressure ulcers, Health care protocol. Bloomington, MN: Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI); March 2007.

30. Preventing pressure ulcers and skin tears. In: Capezuti E., Zwicker D., Mezey M., Fulmer T., editors. Evidenced-based geriatric nursing protocols for best practice. ed 3. New York: Springer; 2008:403-429.

31. Bridel J. The aetiology of pressure sores. J Wound Care. 1993;2:230-238.

32. Berlowitz D., Wilking S. Risk factors for pressure sores: a comparison of cross-sectional and cohort-derived data. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1989;37:1043-1050.

33. Braden B., Bergstrom N. A conceptual scheme for the study of the aetiology of pressure sores. Rehabil Nurs. 1987;12:12-16.

34. Cullum N., Clark M. Intrinsic factors associated with pressure sores in elderly people. J Adv Nurs. 1992;17:427-431.

35. Lowthian P.T. Underpads in the prevention of decubiti. In: Kennedy R.M., Cowden J.M., Scalesc J.T., editors. Bed sores biomechanics: proceedings of a seminar on tissue viability and clinical applications. Baltimore: University Park Press; 1976:141-145.

36. Armstrong D., Bortz P. An integrative review of pressure relief in surgical patients. AORN J. 2001;73:647-648.

37. Papantonio C.T., Wallop J.M., Kolodner K.B. Sacral ulcers following cardiac surgery: incidence and risk. Adv Wound Care. 1994;7:24-36.

38. Hoshowsky V.M., Schramm C.A. Intraoperative pressure sore prevention: an analysis of bedding materials. Res Nurs Health. 1994;17:333-339.

39. Hicks D.J. An incidence study of pressure sores following surgery. In: ANA Clinical Session: 1970 Miami. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1970:49-54.

40. Aronovitch S.A. Intraoperatively acquired pressure ulcer prevalence: a national study. J Wound Ostomy Cont Nurs. 1999;26:130-136.

41. Grous C.A., Reilly N.J., Gift A.G. Skin integrity in patients undergoing prolonged operations. J Wound Ostomy Cont Nurs. 1997;24:86-91.

42. Bergstom N. Pressure ulcer treatment. Am Fam Physician. 1995;51:1207-1222.

43. Evans J.M., Andrews K.L., Chutka D.S., et al. Pressure ulcers: prevention and management. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70:789-799.

44. Nawoczenski D.A. Pressure sores: prevention and management. In: Buchanan L.E., Nawoczenski D.A., editors. Spinal cord injury: concepts and management approaches. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1994:99-121.

45. Alterescu V., Alterescu K.B. Pressure ulcers: assessment and treatment. Orthop Nurs. 1992;11:37-49.

46. Kemp M.G., Faan C., Krouskop T.A. Pressure ulcers. Reducing incidence and severity by managing pressure. J Gerontol Nurs. 1994;20:27-34.

47. Norton D., McLaren R., Exton-Smith A.N. An investigation of geriatric nursing problems in the hospital,. London: National Corporation for the Care of Old People; 1962. Center for Policy on Aging Report

48. Minnis R.J., Sutton R.A., Duffus A., Mattison R. Underseat pressure distribution in the sitting spinal injury person. Paraplegia. 1984;22:297-304.

49. Maklebust J. Pressure ulcers: etiology and prevention. Nurs Clin North Am. 1987;22:359-377.

50. Frantz R., Gardner S. Clinical concerns: management of dry skin. J Geront Nurs. 1994;20:15-18. 45

51. ICSI. Pressure ulcer treatment: health care protocol. Bloomington, MN: Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement; January 2008.

52. Breslow R.A. Nutrition and air-fluidized beds: a literature review. Adv Wound Care. 1994;7:57-62.

53. Bergstrom N., Braden B. A prospective study of pressure sore risk among institutionalized elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:747-758.

54. Finucane T.E. Malnutrition, tube feeding and pressure sores: data are incomplete. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43:447-451.

55. Lamid S., Ghatit A.Z. Smoking, spasticity and pressure sores in spinal cord injured patients. Am J Phys Med. 1983;62:300-306.

56. Maklebust J. An update on horizontal patient support surfaces. Ostomy Wound Manage. 1999;45:70S-77S. (Suppl 1A)

57. Allmann R.M. Pressure ulcers among the elderly. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:850-853.

58. Bennett R.G., Bellantoni M.F., Ouslander J.G. Air-fluidized bed treatment of nursing home patients with pressure sores. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1989;37:235-242.

59. Graff M.K., Bryant J., Beinlich N. Preventing heel breakdown. Orthop Nurs. 2000;19:63-69.

60. Taylor T.V., Rimmer J., Day B., et al. Ascorbic acid supplementation in the treatment of pressure sores. Lancet. 1974;2:544-546.

61. Lewis V.L., Bailey M.H., Pulawski G., et al. The diagnosis of osteomyelitides in patients with pressure sore. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1988;81:229-232.

62. Cutler N.R., Seifert R.D., Sramek J.J. Fleroxacin treatment of stage IV pressure ulcers with associated osteomyelitis. Ann Pharmacother. 1994;28:117.

63. Cullum N., Nelson E.A., Flemming K., Sheldon T. Systematic reviews of wound care management: (5) beds; (6) compression; (7) laser therapy, therapeutic ultrasound, electrotherapy and electromagnetic therapy. Health Technol Assess. 2001;5:1-221.

64. Young J.S., Burns P.E. Medical changes incurred by spinal cord injury patients during first 6 years following injury. Sci Digest. 1982;4:19-26.

65. Honde C., Derks C., Tudor D. Local treatment of pressure sores in the elderly: amino acid copolymer membrane versus hydrocolloid dressing. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42:1180-1183.

66. Ovington L.F. Dressings and adjunctive therapies: AHCPR guidelines revisited. Ostomy Wound Manage. 1999;45:94S-106S.

67. Rodeheaver G.T. Pressure ulcer debridement and cleansing: a review of current literature. Ostomy Wound Management. 1999;45:80S-85S.

68. Moore Z.E., Cowman S. Wound cleansing for pressure ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Revs. 2005;4:CD004983.

69. Mulder G.D. Treatment of open-skin wounds with electric stimulation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1991;72:375-377.

70. Grimi P.S., Gottlich I.J., Boddie A., Batson I. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy. JAMA. 1990;26:2216-2220.

71. Ter Riet G., Kessels A.G.H., Knipchild P. Randomized clinical trial of ultrasound treatment for pressure ulcers. BMJ. 1995;310:1040-1041.

72. Brown G.I., Nanney Z.B., Griffey J., et al. Enhancement of wound healing by topical treatment with epidural growth factor. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:76-79.

73. Patterson J.A., Bennet R.G. Prevention and treatment of pressure sores. Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43:919-927.

74. Mulder G.D. Evaluation of three nonwoven sponges in the debridement of chronic wounds. Ostomy Wound Manage. 1995;41:62-67.

75. Sheman R.A., Wyle F., Vulpe M. Maggot therapy for treating pressure ulcers in spinal cord injury patients. J Spinal Cord Med. 1996;18:71-74.