Skin and Lacrimal Drainage System

Skin

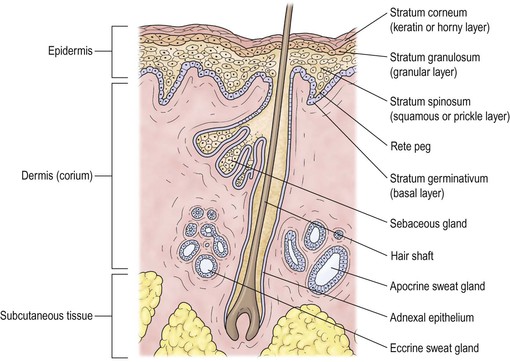

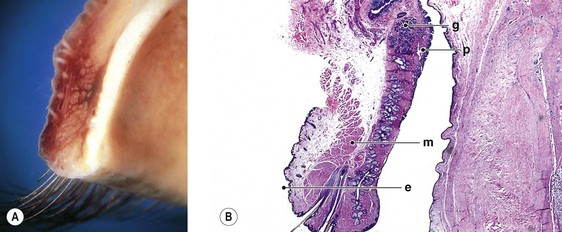

Normal Anatomy (Figs. 6.1 and 6.2)

Epidermis

Lid skin is quite thin.

III. Expression of immunohistochemical markers for cytokeratins, mucin, and stem cells varies considerably among the various epithelia at the mucocutaneous junction of the eyelid.

B. Reactivity also is found for MUC1 and MUC4 but not for MUC5AC.

Dermis

The dermis is sparse, composed of delicate collagen fibrils, and contains the vasculature and epidermal appendages, sebaceous glands, apocrine and eccrine sweat glands, and hair complexes.

Subcutaneous Tissue

The subcutaneous layer is mostly composed of adipose tissue.

Terminology

Orthokeratosis and Parakeratosis

Dyskeratosis

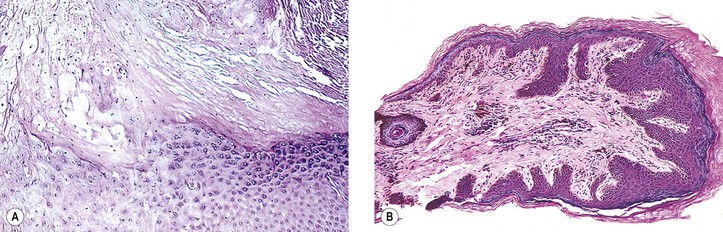

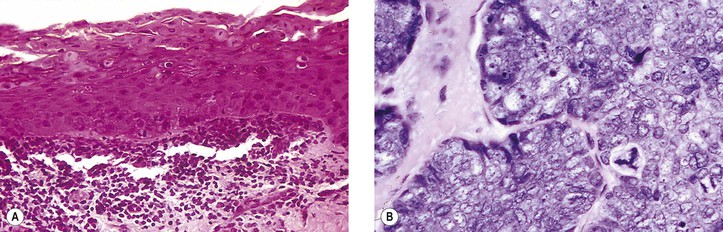

I. Dyskeratosis is keratinization of individual cells within the stratum spinosum, where the cells are not normally keratinized (Fig. 6.4A; see Fig. 7.18). The keratinizing cells show abundant pink (eosinophilic) cytoplasm and small, normal-appearing nuclei.

Atrophy

I. Atrophy (see subsection Atrophy later, under Aging, and Fig. 6.8) is (1) thinning of the epidermis; (2) smoothing or diminution (effacement) of rete ridges (“pegs”); (3) disorder of epidermal architecture; (4) diminution or loss of epidermal appendages such as hair; and (5) alterations of the collagen and elastic dermal fibers.

Atypical Cell

I. An atypical cell (see Fig. 6.4B) is one in which the normal nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio is altered in favor of the nucleus, which stains darker than normal (hyperchromasia), may show an abnormal configuration (giant form or multinucleated form), may have an abnormal nuclear configuration (e.g., indented, cerebriform, multinucleated), or may contain an abnormal mitotic figure (e.g., tripolar metaphase). If sufficiently atypical, according to generally accepted criteria, the cell may be classified as cancerous.

Leukoplakia

Polarity

II. Complete loss of polarity (see Fig. 7.22) has occurred when the cells at the surface are indistinguishable from the cells at the base (e.g., in squamous cell carcinoma or malignant melanoma).

Congenital Abnormalities

Dermoid and Epidermoid Cysts

See Chapter 14.

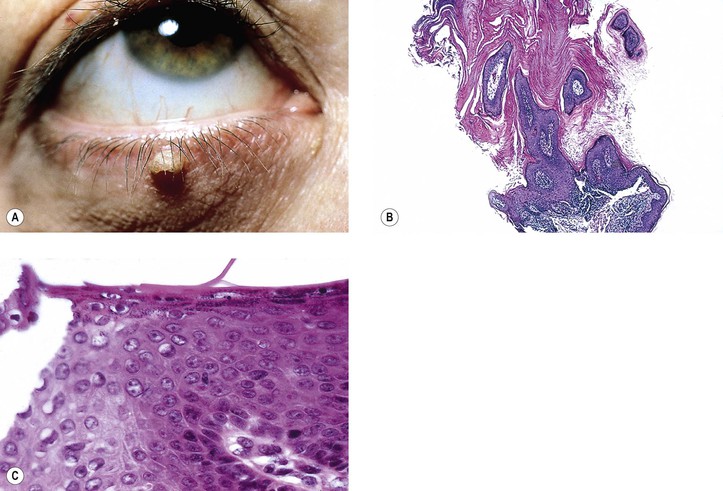

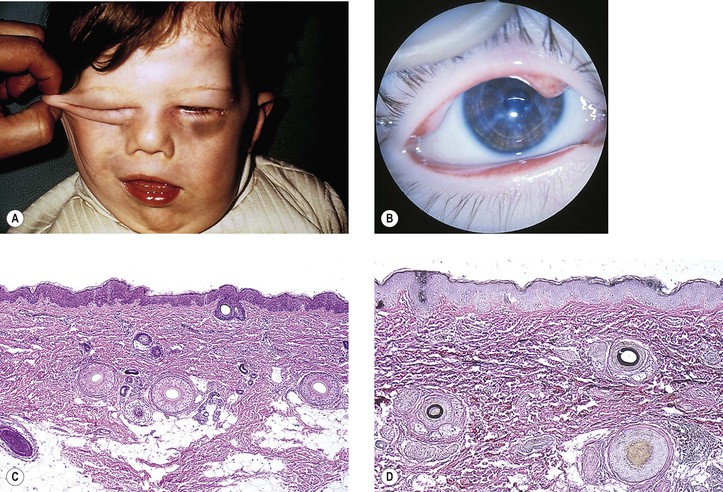

Phakomatous Choristoma

I. Phakomatous choristoma (Fig. 6.6) is a rare, congenital, choristomatous tumor (i.e., a tumor of tissue not normally found in the area) of lenticular anlage, usually involving the inner aspect of the lower lid.

Miscellaneous Choristomas and Hamartomas

III. Neurocutaneous pattern syndromes are a group of disorders characterized by congenital abnormalities involving both the skin and the nervous system for which no identifiable cause has been isolated. Examples are encephalocraniocutaneous lipomatosis, oculocerebrocutaneous syndrome, and linear nevus sebaceous syndrome.

IV. Caliber persistent artery refers to a large-caliber artery that is present adjacent to an epithelial or mucosal surface.

Microblepharon

Microblepharon is a rare condition in which the lids are usually normally formed but shortened; the shortening results in incomplete lid closure.

Ectopic Caruncle

A clinically and histologically normal caruncle may be present in the tarsal area of the lower lid.

Lid Margin Anomalies

Ptosis

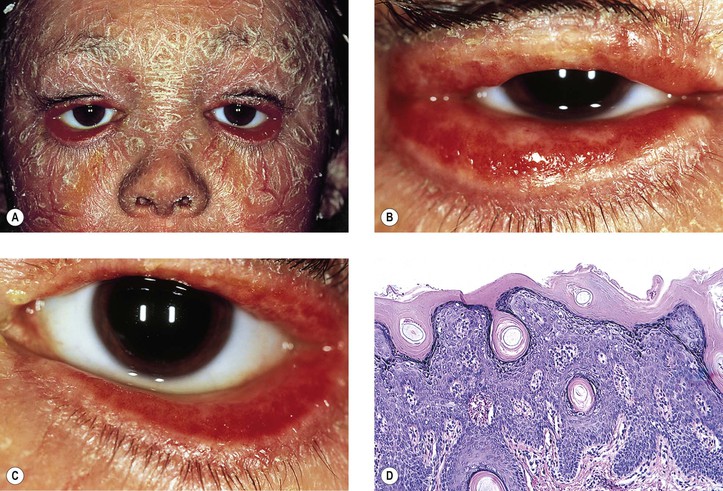

Ichthyosis Congenita

I. Ichthyosis (Fig. 6.7) can be divided into four types:

A. Autosomal-dominant ichthyosis vulgaris (onset usually in first year of life)

C. X-linked recessive ichthyosis vulgaris [the rarest type (Xp22.32), onset at 1–3 weeks]

D. Autosomal-recessive ichthyosis congenita with a severe harlequin type and a less severe lamellar type (onset at birth)

2. Intact cross-linkage of cornified cell envelopes is required for epidermal tissue homeostasis.

II. All types have in common dryness of the skin with variable amounts of profuse scaling.

Only in the autosomal-recessive type do ectropion of the lids and conjunctival changes develop.

III. Cicatricial ectropion is a common finding in recessive ichthyosis congenita.

V. Histologically, the epidermis is thickened and covered by a thick, dense, orthokeratotic scale.

Xeroderma Pigmentosum

III. Histology

Aging

Atrophy

See subsection Atrophy, earlier, under Terminology.

Senile Ectropion and Entropion

I. An accentuation of the aging changes may result in an ectropion (turning-out) or an entropion (turning-in) of the lower lid.

II. Histologically, both ectropion and entropion show chronic nongranulomatous inflammation and cicatrization of the skin and conjunctiva.

B. Entropion shows increased atrophy of the orbital septum and tarsus.

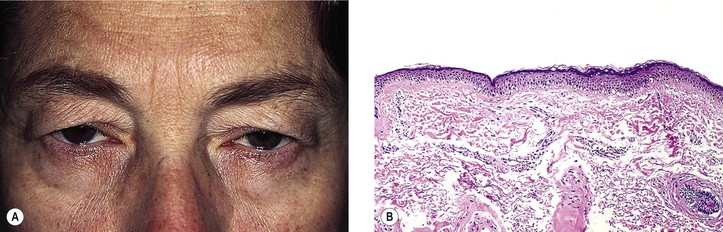

Dermatochalasis

I. Dermatochalasis (Fig. 6.8) is an aging change characterized by lax, redundant skin of the lids. The folds may cover the palpebral fissure, even impairing vision.

II. Histologically, the epidermis appears thin and smooth with decreased or absent rete ridges.

Inflammation

Terminology

I. Dermatitis (synonymous with eczema, eczematous dermatitis)

II. Blepharitis (dermatitis of the lids is called blepharitis)

A. Blepharitis is a simple diffuse inflammation of the lids.

B. Seborrheic blepharitis refers to a specific type of chronic blepharitis primarily involving the lid margins and often associated with dandruff and greasy scaling of the scalp, eyebrows, central face, chest, and pubic areas.

1. Red, inflamed lid margins and yellow, greasy scales on the lashes are characteristic.

C. Blepharoconjunctivitis refers to a specific type of chronic blepharitis involving the lid margins primarily and the conjunctiva secondarily.

1. Sensitivity to Staphylococcus is the likely cause.

D. Cellulitis refers to a specific type of acute, infectious blepharitis primarily involving the subepithelial tissues.

1. Histologically, polymorphonuclear leukocytes, vascular congestion, and edema predominate.

2. Bacteria, especially Streptococcus, are the usual cause.

III. Hordeolum (Fig. 6.9)

A. An external hordeolum (stye) results from an acute purulent inflammation of the superficial glands (sweat and sebaceous) and hair follicles of the eyelids.

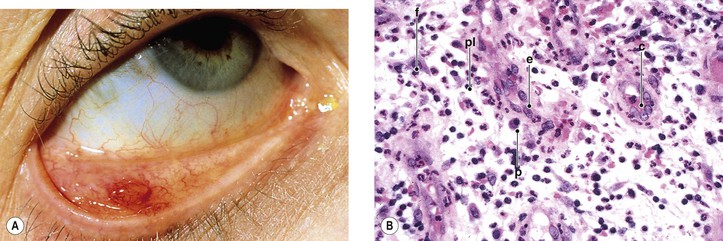

IV. Chalazion (Fig. 6.10)

B. If the chalazion ruptures through the tarsal conjunctiva, granulation tissue growth (fibroblasts, young capillaries, lymphocytes, and plasma cells) may result in a rapidly enlarging, painless, polypoid mass (granuloma pyogenicum; Fig. 6.11).

C. Histologically, a zonal lipogranulomatous inflammation is centered around clear spaces previously filled with lipid but dissolved out during tissue processing.

1. Polymorphonuclear leukocytes, plasma cells, and lymphocytes may also be found in abundance.

V. Acne rosacea

C. Histology

2. Type 2 shows hyperplasia of sebaceous glands along with the findings seen in type 1.

Viral Diseases

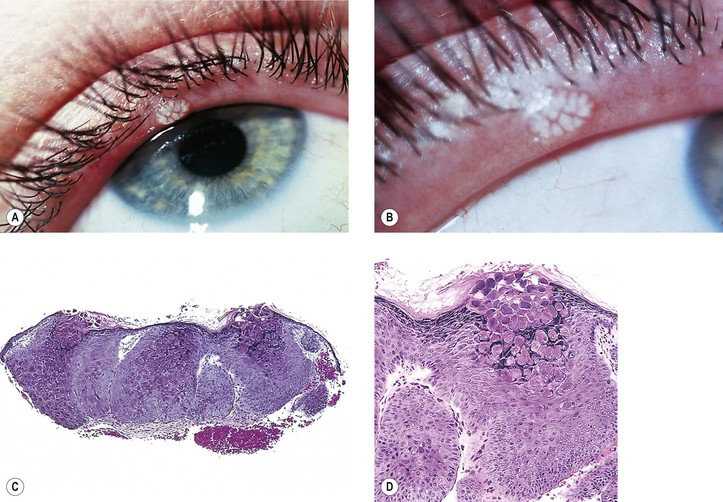

I. Molluscum contagiosum (Fig. 6.12)

B. The large pox virus replicates in the cytoplasm and is seen histologically as large, homogeneous, purple, intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies (molluscum bodies) in a markedly acanthotic epidermis.

II. Verruca (wart; Fig. 6.13)

C. Histologically, massive papillomatosis, marked by acanthosis, parakeratosis, and orthokeratosis and containing collections of serum in the stratum corneum at the tips of the digitations, is seen.

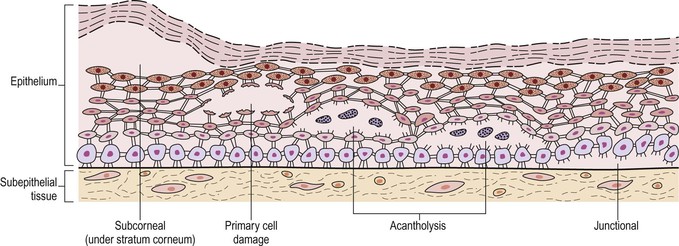

B. Histologically, an intraepidermal vesicle characterizes all five diseases (see Fig. 6.5).

Bacterial Diseases

I. Impetigo

Fungal and Parasitic Diseases

See subsections on fungal and parasitic nontraumatic infections in Chapter 4.

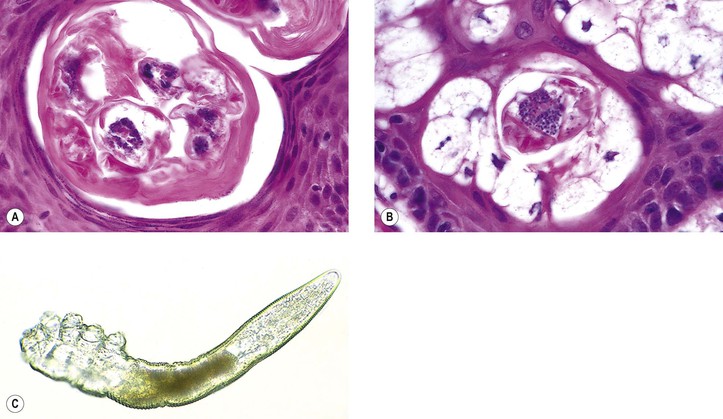

C. Histologically, the mite is often seen as an incidental finding in a hair follicle in skin sections.

D. No inflammatory reaction is associated with the mite.

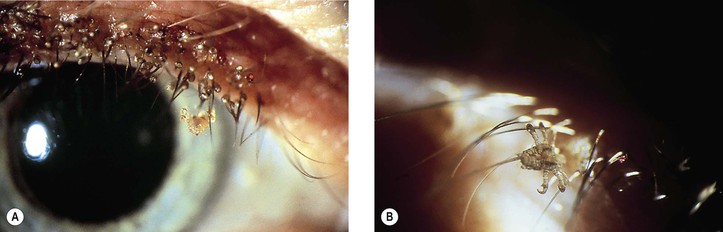

II. Phthirus pubis (Fig. 6.15)

B. Transmission from the primary site of infestation, the pubic hair, is usually by hand.

1. The louse, or several lice, grips the bottom of the lash with its claw.

2. The ova (nits) are often present in considerable numbers, adhering to the lashes.

Lid Manifestations of Systemic Dermatoses or Disease

Ichthyosis Congenita

See section Congenital Abnormalities earlier in this chapter.

Xeroderma Pigmentosum

See section Congenital Abnormalities earlier in this chapter.

Pemphigus

See Chapter 7.

Ocular involvement in pemphigus vulgaris occurs rarely and is usually limited to the conjunctiva and/or the eyelids. In contrast, pemphigus foliaceus involves the skin of the eyelid and not the conjunctiva.

Ehlers–Danlos Syndrome (“India-Rubber Man”)

Cutis Laxa

I. In cutis laxa (Fig. 6.16), the extensible skin hangs in loose folds over all parts of the body, especially in those areas where it is normally loose (e.g., around the eyes).

A. The lungs may be involved, causing emphysema.

B. Cor pulmonale may result in early death.

C. Autosomal-dominant, recessive, and acquired forms have been reported.

III. Ocular findings include hypertelorism, blepharochalasis, ectropion, and corneal opacities.

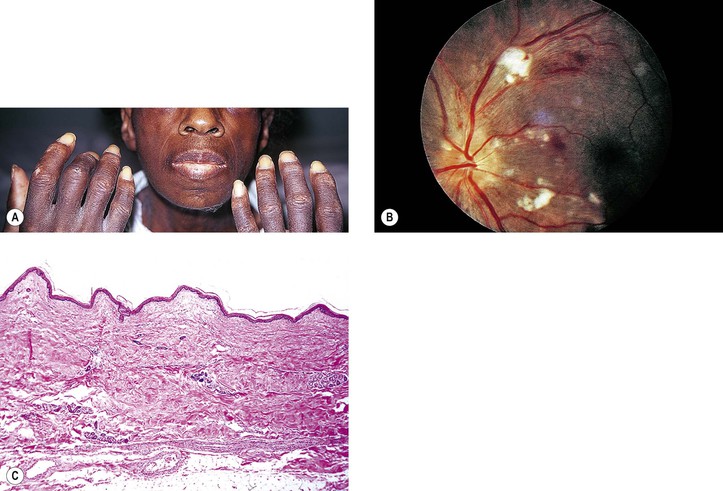

Pseudoxanthoma Elasticum

A. The skin of the face, neck, axillary folds, cubital areas, inguinal folds, and periumbilical area (often with an umbilical hernia) becomes thickened and grooved, with the areas between the grooves diamond-shaped, rectangular, polygonal, elevated, and yellowish (resembling chicken skin).

1. The skin in the involved areas becomes lax, redundant, and relatively inelastic.

2. The skin changes may not be noted until the second decade of life or later.

B. The eyes show angioid streaks (see Fig. 11.38), sometimes with subretinal neovascularization.

Erythema Multiforme

Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis

I. Toxic epidermal necrolysis (Lyell’s disease; epidermolysis necroticans combustiformis; acute epidermal necrolysis; scalded-skin syndrome) really consists of two different diseases, Lyell’s disease (subepidermal type or true toxic epidermal necrolysis—probably a variant of severe erythema multiforme) and Ritter’s disease (subcorneal type or staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome—not related to toxic epidermal necrolysis).

B. Staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome (Ritter’s disease) is not related to erythema multiforme, occurs largely in the newborn and in children younger than five years, and occurs as an acute disease.

1. Its onset begins abruptly with diffuse erythema accompanied by severe malaise and high fever.

3. The disease runs an acute course and is fatal in fewer than 4% of cases.

Epidermolysis Bullosa

Contact Dermatitis

I. An allergenic or irritating substance applied to the skin may result in contact dermatitis, which is a type IV immunologic reaction requiring a primary exposure, sensitization, and re-exposure to an allergen, and then an immunologic delay before clinical expression of the dermatitis.

A. Contact dermatitis is one of the most common abnormal conditions affecting the lids.

C. Contact dermatitis may be present in three forms:

1. An acute form with diffuse erythema, edema, oozing, vesicles, bullae, and crusting

2. A chronic form with erythema, scaling, and thick, hard, leathery skin (lichenification)

3. A subacute form showing characteristics of acute and chronic forms

II. Histology

B. In the chronic stage, there is acanthosis, orthokeratosis, and some parakeratosis together with elongation of rete pegs.

1. Mild spongiosis is present, but vesicle formation does not occur.

2. In the dermis, perivascular lymphocytes, eosinophils, histiocytes, and fibroblasts are found.

Collagen Diseases

I. Dermatomyositis (see Chapter 14)

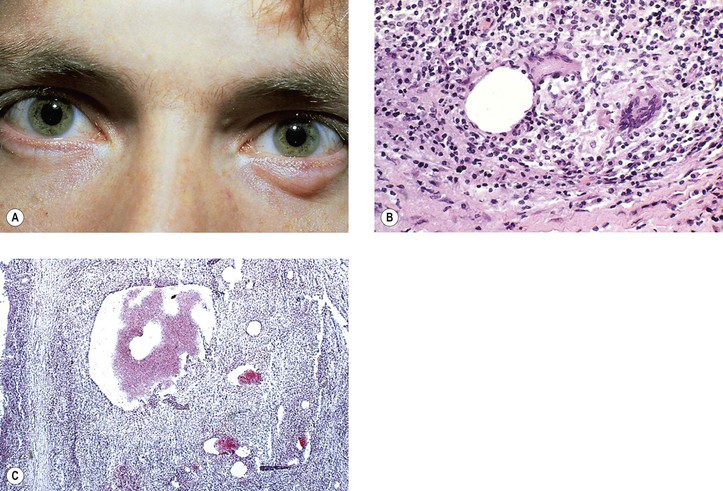

II. Periarteritis (polyarteritis) nodosa

B. Histologically, four stages may be seen:

4. The fibrotic stage: Healing ends with scar formation.

III. Lupus erythematosus can be subdivided into three types:

1. Chronic discoid, which is limited to the skin

a. Discoid lupus erythematosus involving the eyelids is rare. It may present as madarosis.

b. Periorbital edema and erythema are rare cutaneous manifestations of discoid lupus erythematosus.

2. Intermediate or subacute, which has systemic symptoms in addition to skin lesions

3. Systemic, which is dominated by visceral lesions

IV. Scleroderma (Fig. 6.17) exists in two forms: (1) a benign circumscribed (morphea) form, which almost never progresses or transforms to the systemic form, and (2) a systemic form (progressive systemic sclerosis), which may prove fatal.

C. Histologically, the morphea and the systemic forms are similar, if not identical.

3. Late stage: Dermis is thickened by the addition of new collagen at the expense of subcutaneous tissue. Inflammation is minor or absent.

a. The subcutaneous fat is replaced by collagen, and blood vessels are fibrotic.

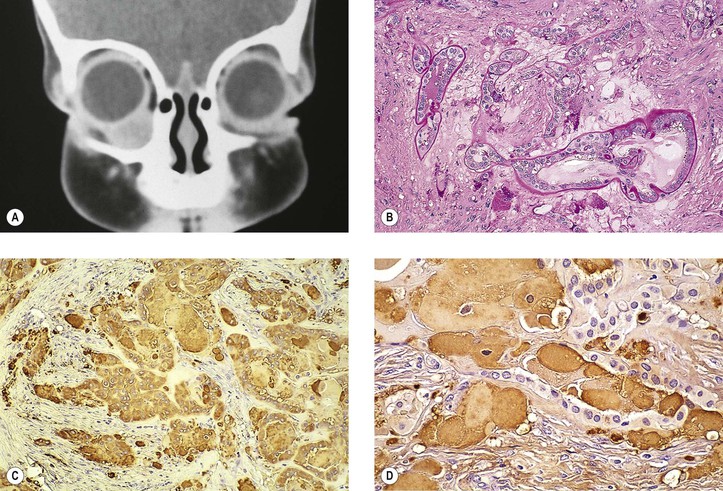

Granulomatous Vasculitis

A. Classic form: characterized by generalized small-vessel vasculitis, necrotizing granulomas, focal necrotizing glomerulonephritis, and vasculitis of the upper and lower respiratory tract.

3. A limited form of Wegener’s granulomatosis lacks renal involvement (see Fig. 8.64).

4. In both classic and limited forms, most of the ocular findings can occur.

C. Histologically, the classic triad of necrotizing vasculitis (granulomatous and disseminated small-vessel), tissue necrosis, and granulomatous inflammation are characteristic. The vasculitis can be seen in three forms:

Vasculitis-Like Disorders and Leukemia/Lymphoma

I. Natural killer (NK) T-cell lymphoma (polymorphic reticulosis or angiocentric T-cell lymphoma)

B. NK/T-cell malignancies are uncommon and were previously known as polymorphic reticulosis or angiocentric T-cell lymphomas. The World Health Organization further divides these lesions into NK/T-cell lymphoma (nasal and extranasal) type and aggressive NK-cell leukemia.

1. Its lymphoma cells are CD2+, CD56+, and CD3ε+.

C. Relatively common in Asia, Mexico, and South America, but extremely rare in most Western countries.

E. Apoptosis, necrosis, and angioinvasion are typical features of the lymphoma.

J. Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) can encode multiple genes that drive cell proliferation and confer resistance to cell death, including two viral proteins that mimic the effects of activated cellular signaling proteins.

L. NK/T-cell lymphoma has occasionally involved the eye.

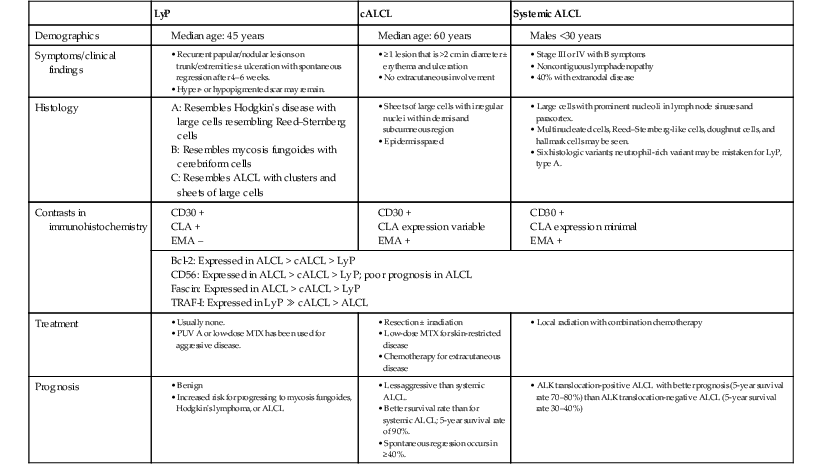

II. CD30+ lymphoid proliferations (Table 6.1)

B. 30% of all cutaneous T-cell lymphomas.

C. Spectrum of clinical aggressiveness.

D. Proper diagnosis requires clinical and pathologic correlation.

TABLE 6.1

Clinical and Pathologic Findings in CD30+ Lymphoid Proliferations

ALCL, systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma; ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase; cALCL, primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma; CLA, cutaneous lymphocyte antigen; EMA, epithelial membrane antigen: LyP, lymphomatoid papulosis; MTX, methotrexate; PUVA, psoralen plus ultraviolet A; TRAF-I, tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor-1.

(From Sanka RK, Eagle RC, Jr., Wojno TH, Neufeld KR, Grossniklaus HE: Spectrum of CD30+ lymphoid proliferations in the eyelid lymphomatoid papulosis, cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma, and anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Ophthalmology 117:343, 2010.)

III. Mycosis fungoides

A. Most common type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma but rarely involve eyelids.

B. Recalcitrant clinical course.

C. Three classic phases: macular or patch, infiltrative or plaque, and tumor stage.

D. Among the eyelid presentations are ulceration, plaques, facial swelling, and eyelid ectropion.

IV. Other T-cell lymphomas involving the eyelids have been reported.

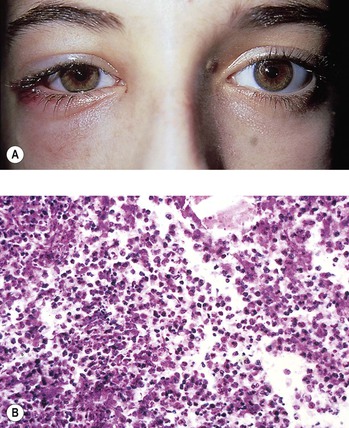

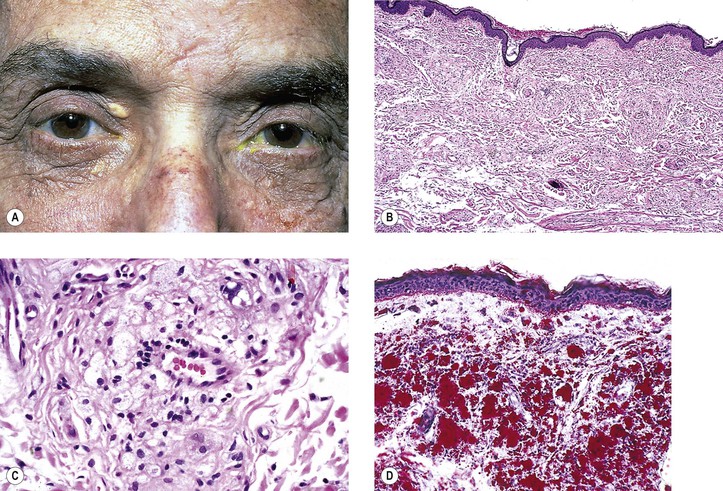

Xanthelasma

I. Xanthelasma (Fig. 6.18) most commonly occurs in middle-aged or elderly people who usually, but not always, have normal serum cholesterol levels.

B. It may occur in primary hypercholesterolemia or with nonfamilial serum cholesterol elevation.

II. After initial surgical excision, the recurrence rate is probably in the 10 to 20% range.