26.2 Immunological disorders283

26.3 Genetic disorders283

The skin is a multifunctional organ involved in structural support, protection from injury and infection and temperature regulation. When these functions are dramatically disturbed – in extensive burn injuries, for example – patients are at risk of fatal metabolic and fluid homeostasis disruption or overwhelming bacterial infection. Skin neoplasms are very common in white-skinned races, with malignant melanoma rising rapidly in incidence. There are many inflammatory diseases of the skin that cause significant morbidity and cosmetic problems.

26.1. Inflammation and infection

You should:

• understand the terminology used to described skin lesions macroscopically

• know how inflammatory skin diseases can be classified according to the pattern of microscopic changes; this will help your understanding of clinical dermatology

• understand the classification and complications of burns.

One of the common difficulties students encounter when learning about skin diseases is the large number of specific terms used to describe both macroscopic and microscopic appearances. Common naked-eye and microscopic descriptive terms are shown in Box 31.

Box 31

Naked-eye:

• Macule – flat area of altered colour

• Papule – small raised lesion

• Plaque – slightly raised, flat-topped lesion

• Erythema – reddening of the skin

• Vesicle – small fluid-filled lesion

• Bulla – larger fluid-filled lesion

• Blister – non-specific term that includes vesicle and bulla

Microscopic:

• Hyperkeratosis – increased thickness of the superficial keratin

• Parakeratosis – presence of residual nuclear material within the superficial keratin (implies abnormal maturation)

• Spongiosis – intercellular oedema in the epidermis, characteristically seen in eczematous lesions

• Acanthosis – thickening of the epidermis

• Acantholysis – discohesion, ‘falling apart’, of epidermal cells

Inflammatory skin diseases can be classified according to the pattern of histological changes (Table 60).

| Spongiotic | Spongiosis – intraepidermal oedema | Eczema |

|---|---|---|

| Psoriasiform | Regular epidermal hyperplasia (thickening) | Psoriasis |

| Lichenoid | Damage to basal epidermis, often with chronic inflammatory infiltrate along dermo-epidermal junction | Lichen planus |

| Lupus erythematosus | ||

| Erythema multiforme | ||

| Graft-versus-host disease | ||

| Vesico-bullous | Vesicle or blister (bulla) formation | Pemphigoid |

| Dermatitis herpetiformis | ||

| Pemphigus | ||

| Granulomatous | Chronic inflammation with aggregates of enlarged (epithelioid) histiocytes | Sarcoidosis |

| Infection (tuberculosis, fungal) | ||

| Reaction to foreign material | ||

| Vasculitis | Inflammation of vessel walls | Primary cutaneous vasculitis |

| Skin involvement by systemic vasculitis | ||

| Panniculitis | Inflammation of the subcutaneous fat | Erythema nodosum |

Eczema

Eczema is a common inflammatory skin disease presenting clinically with red papules or plaques containing small vesicles, which may itch, ooze and crust. There are several clinical subtypes. The characteristic histological feature is intercellular oedema in the epidermis (spongiosis), which separates the keratinocytes and can cause vesicle formation. Chronic inflammation with lymphocytic infiltration of the epidermis and dermis is often seen. Pathogenesis is variable and includes:

• direct toxic effects (irritant contact dermatitis)

• delayed hypersensitivity reaction (allergic contact dermatitis)

• combination of IgE-mediated and T cell-mediated reaction (atopic eczema).

Psoriasis

Psoriasis is a common chronic relapsing dermatitis that classically manifests as circumscribed red skin plaques often several centimetres in diameter, with silvery surface scale. Extensor surfaces of knees and elbows, the sacral region and the scalp are common sites. Nail changes are common and arthritis develops in a small percentage of patients. Onset is usually in early adult life. The pathogenesis is unclear but there is hyperproliferation of keratinocytes, with the epidermal turnover time reduced from the normal 13days to 3–4days. The histological features of classical psoriasis are:

• regular epidermal hyperplasia (thickening)

• parakeratosis (retained nuclei within the surface keratin layer)

• thinning of the granular layer

• neutrophil microabscesses

• increased mitotic activity (cell turnover).

Lichen planus

Lichen planus presents clinically as multiple small itchy violet papules, around the wrist and elbows. Oral and genital lesions also occur. Skin lesions often resolve after several months or years. Histological features include:

• irregular epidermal hyperplasia

• damage to the basal epidermis with vacuolation and apoptotic epidermal cells

• band-like (‘lichenoid’) chronic inflammatory infiltrate at the dermo-epidermal junction.

Erythema multiforme

Erythema multiforme (EM) is an uncommon but potentially serious hypersensitivity response to certain infections (herpes simplex and Mycoplasma) and drugs (including sulphonamides, penicillin and aspirin). Clinical lesions include red macules, papules and vesicles. The characteristic ‘target’ lesion has a pale, raised or eroded centre and erythematous (red) rim. Symmetrical involvement of the limbs is most commonly seen. Stevens–Johnson syndrome is severe erythema multiforme with oral mucosal lesions. Toxic epidermal necrosis is the most serious manifestation of EM, with a high risk of systemic sepsis and fluid imbalance due to extensive loss of skin and mucosal epithelium; mortality is 35%. Histological examination shows a lichenoid inflammatory infiltrate with epidermal cell apoptosis.

Vesico-bullous diseases

Vesico-bullous diseases are classified according to the site of the vesicle formation, which may be within the epidermis or at the dermo-epidermal junction. The pathogenesis in many cases involves immune complex formation with autoantibodies. Examples are shown in Table 61. Many of these diseases are described further below.

| Site of blistering | Disease example | Pathogenesis |

|---|---|---|

| Within epidermis | Impetigo | Bacterial infection |

| Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome | ||

| Pemphigus | Autoantibody formation | |

| Spongiotic dermatitis | Extreme intercellular oedema | |

| At dermo-epidermal junction | Epidermolysis bullosa | Hereditary defect in proteins that anchor basal epidermis cells to basement membrane |

| Porphyria | Enzyme deficiency causing skin fragility | |

| Dermatitis herpetiformis | IgA antibody deposition | |

| Pemphigoid | Autoantibody formation |

Burns

Burns can be caused by hot liquids (scalds), gases or solids, as well as fire. Burn injuries are classified as:

• partial thickness (first and second degree burns)

• full thickness (third degree burns).

In first degree burns there is endothelial injury and leakage of intravascular fluid into the surrounding tissue. There is vascular congestion with pain and erythema, but no skin necrosis. Second degree burns show epidermal necrosis with blistering as the epidermis separates from the dermis. Regeneration of the skin surface cells can occur from adjacent viable epidermis or from surviving skin adnexal structures. More severe damage occurs in third degree burns, with necrosis of the epidermis and dermis. As the extent of severe burn injuries increases, so does the risk of serious or fatal complications, including:

• septic shock

• renal failure

• adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)

• scarring and contractures.

Skin grafting is often required for healing of third degree burns.

Infectious disease

Skin infections are common, with a wide variety of potential pathogens, including:

• Bacteria

• impetigo (staphylococcal or streptococcal infection, particularly in children)

• staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (infants and children)

• furuncles (‘boils’)

• cellulitis

• cutaneous tuberculosis.

• Viruses

• varicella zoster (chicken pox and shingles)

• verrucae (common warts – human papilloma virus infection)

• molluscum contagiosum (poxvirus).

• Fungi

• Candida

• tinea (ringworm, athlete’s foot).

• Arthropods

• scabies

• lice.

26.2. Immunological disorders

Lupus erythematosus

Lichenoid inflammatory pattern skin lesions may be part of systemic lupus erythematosus or more commonly isolated cutaneous disease, called discoid lupus erythematosus. Immunoglobulins and complement are deposited along the dermo-epidermal junction.

Graft-versus-host disease

Recipients of immunocompetent bone marrow transplants often develop lesions in the skin, gastrointestinal tract and liver, when grafted lymphocytes attack host tissue. Cutaneous graft-versus-host disease has a lichenoid pattern.

Bullous pemphigoid

Bullous pemphigoid is a blistering skin disease that occurs in the elderly. Up to 90% have IgG autoantibodies against the bullous pemphigoid major antigen located in the epidermal basement membrane. The vesicles and bullae usually contain eosinophils.

Pemphigus

Pemphigus is an intraepidermal blistering disease with autoantibodies to various structural proteins involved in intercellular adhesion.

Dermatitis herpetiformis

Dermatitis herpetiformis is a subepidermal blistering disease characterised by IgA antibody deposition, although the exact pathogenesis is unclear. There is a strong association with coeliac disease.

26.3. Genetic disorders

Epidermolysis bullosa

Epidermolysis bullosa is a rare, blistering, skin disease with several subtypes that have dominant or recessive inheritance. Some variants are lethal in early life, others cause disfiguring scars with increased risk of developing squamous cell carcinoma. Blisters develop at sites of skin trauma or rubbing.

Xeroderma pigmentosum

Xeroderma pigmentosum is a rare, autosomal-recessive disease with defective DNA repair. There is extremely high incidence of epidermal and melanocytic malignancies.

26.4. Neoplasia

You should:

• know the pathology of the common skin cancers – basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma and malignant melanoma

• understand the spectrum of benign and malignant melanocytic lesions in the skin and be able to recognise clinically suspicious ‘moles’

• be able to interpret the prognostic information provided in a histopathology report of a malignant melanoma.

Neoplasms of the skin can arise from many of the component cells and tissues. The most common tumours arise from the epidermal cells and from melanocytes. The adnexal structures – eccrine sweat glands, sebaceous glands, hair follicles and apocrine glands – can give rise to a huge range of tumours, both benign and malignant (see Table 62).

| Benign | Malignant | |

|---|---|---|

| Epidermal | Basal cell papilloma | Basal cell carcinoma |

| Squamous cell papilloma | Squamous cel carcinoma | |

| Melanocytic | Naevus (junctional, compound, intradermal, Spitz) | Malignant melanoma |

| Adnexal | Syringoma | Adnexal carcinomas (rare) |

| Pilomatrixoma | ||

| Cylindroma | ||

| Lymphoid | Cutaneous T cell lymphoma | |

| Cutaneous B cell lymphoma | ||

| Connective tissue | Dermatofibroma | Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans |

| Lipoma | Liposarcoma | |

| Haemangioma | Kaposi’s sarcoma | |

| Angiosarcoma | ||

| Neurofibroma | Malignant nerve sheath tumours | |

| Leiomyoma | Leiomyosarcoma |

Basal cell papilloma

Basal cell papilloma is also known as seborrhoeic keratosis or seborrhoeic wart. It is a common benign warty tumour, arising in adults. It occurs almost anywhere on the body and is often pigmented. Microscopically the tumour consists of papillary projections of uniform cells resembling normal basal epidermal keratinocytes. There is hyperkeratosis and frequent formation of keratin nodules (horn cysts).

Basal cell carcinoma

Basal cell carcinoma is the commonest human malignant neoplasm. It typically arises in chronically sun-exposed skin of older adults; 80% develop on the head or neck. Metastasis is rare but, if untreated, basal cell carcinoma may cause extensive local tissue erosion, hence the historical name of ‘rodent ulcer’. Basal cell carcinoma has several microscopic growth patterns:

• nodular – commonest (70%)

• superficial multifocal

• infiltrative (morphoeic) – highest risk of recurrence.

The tumour cells resemble those of the normal basal epidermis and are recognised histologically by their small hyperchromatic nuclei, mitotic figures and palisading (regular arrangement) of cells at the periphery of the tumour nests.

Squamous cell carcinoma

Squamous cell carcinoma is also a common tumour arising on sun-exposed skin of older adults. The tumour cells resemble those of the suprabasal epidermis in normal skin. Well-differentiated squamous cell carcinomas produce keratin and microscopically show thin cytoplasmic extensions or ‘prickles’, which represent desmosomal cell junctions, between the tumour cells. Squamous cell carcinomas have a low incidence of metastasis to local lymph nodes and distant sites (approximately 1%).

Squamous cell carcinoma often develops within a pre-existing dysplastic epidermal lesion, such as actinic keratosis or Bowen’s disease (epidermal carcinoma in situ). Rarely, squamous cell carcinoma can arise in a chronic ulcer (Marjolin’s ulcer), burn or scar. Immunosuppressed patients (e.g. following renal transplantation) have an increased incidence of squamous cell carcinoma.

Keratoacanthoma

Is a rapidly growing keratotic nodule that resembles well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, both clinically and microscopically, and the distinction between the two lesions can be very difficult. Keratoacanthomas tend to involute spontaneously, but can leave marked scarring.

Melanocytic lesions

Pigmented skin lesions can be due to:

• increased melanin pigmentation of the epidermis without melanocytic proliferation (pigmented basal cell papillomas, lentigo simplex)

• malignant melanoma.

Clinical features that raise suspicion of melanoma in a pigmented lesion include:

• itching, crusting or bleeding

• change in size

• change in colour

• change in shape (irregularity of lesion border)

• size >7mm – although malignant melanomas can be smaller than this.

Benign naevi (singular = naevus)

Benign naevi are extremely common and may be congenital or acquired. Most arise in childhood or adolescence. Naevi are classified according to the distribution of the melanocytic cells:

• junctional (naevus cells confined to epidermis)

• compound (naevus cells in epidermis and dermis)

• intradermal (naevus cells found only in dermis)

• blue naevi (intradermal, composed of spindle cells with marked melanin pigmentation).

Malignant change in acquired naevi is rare. However, large numbers of moles (>50 per individual) do appear to confer an increased risk of melanoma. Up to 10% of giant congenital naevi (>20mm diameter) will develop melanoma within them.

Malignant melanoma

The incidence of melanoma in the UK is rising more rapidly than that of any other malignancy. The pathogenesis is clearly linked to UV-induced cell damage. Individuals with fair skin and hair, a history of sunburn and repeated high-intensity sun exposure are at particular risk. A strong family history is also significant.

Traditionally, classification of melanoma has been by architectural type:

• lentigo maligna melanoma

• superficial spreading melanoma (commonest, >50%)

• acral lentiginous melanoma (palm and soles – rare)

• nodular melanoma.

Lentigo maligna arises mainly on the chronically sun-exposed skin of the head and neck in the elderly. Atypical melanocytes replace the normal basal epidermis. The tumour may be present as an irregular pigmented macule for several years before invasive dermal malignancy with metastatic potential develops.

Superficial spreading melanoma is characterised by atypical melanocytes scattered irregularly at all levels of the epidermis; this pattern is also known as ‘pagetoid spread’. It can develop at any age, and is commonest on the back in males and lower leg in females.

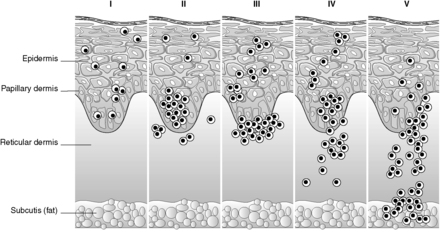

More recently, melanomas have been classified according to their growth pattern into radial growth phase or vertical growth phase. It is proposed that only tumours showing evidence of proliferation in the dermis (vertical growth phase) have the capacity to metastasise (Table 63).

| Radial growth phase melanoma | Vertical growth phase melanoma |

|---|---|

| Tumour grows within epidermis, with only single cells or small nests of melanocytes in the papillary dermis | Tumour usually involves the reticular dermis |

| Melanocyte cell groups in the epidermis larger than those in the dermis | Melanocyte cell groups in the dermis larger than those in the epidermis |

| No dermal mitoses are present | Dermal mitoses are often present |

Classical melanoma cells are ‘epithelioid’ – large polygonal or cuboidal cells with copious cytoplasm and a large single eosinophilic nucleolus. Pigmentation is often found in a percentage of cells, but amelanotic lesions do occur and may be misdiagnosed clinically. Melanoma cells can also be spindle shaped. The histological diagnosis can be confirmed with immunocytochemistry with antibodies to S100 (a marker of neural crest origin) and HMB45 (see Box 32).

Box 32

What is it?

Immunohistochemistry is a histological technique in which labelled antibodies to specific proteins are applied to tissue sections. If the protein antigen is present in the cells they will bind the antibody, which can be detected on microscopy by the attached coloured label.

When is it used?

• To confirm the nature of a cell or tumour when the morphological appearances alone are not diagnostic.

• For prognosis and treatment, e.g. oestrogen receptor status in breast carcinoma.

Examples of commonly used immunohistochemical antibodies

Epithelial markers

• Cam 5.2 (low-molecular-weight cytokeratin)

• AE1/AE3 (a ‘cocktail’ of cytokeratins)

Lymphocyte markers

• LCA (leucocyte common antigen)

• CD3 (T cells)

• CD20 (B cells)

Melanocytic markers

• S100 (also stains neural tissue)

• HMB45 (a marker of melanosomes)

Muscle

• Desmin, myoglobin, anti-smooth muscle actin

Vascular endothelium

• Factor-8-related antigen

Nerve

• S100

Others

• Prostatic-specific antigen (PSA)

• α-Fetoprotein (hepatocellular carcinoma and certain germ cell tumours)

• Oestrogen receptor, HER2 – breast cancer prognosis

The most important prognostic factor in melanoma is the depth of invasion (Breslow thickness), measured from the top of the granular epidermal layer to the deepest dermal melanoma cell. The anatomical depth of invasion is also expressed as the Clark level (Figure 71). More recently, the prognostic importance of sentinel lymph node status in melanoma has been realised. The sentinel node is the specific node (or sometimes nodes) draining the area of a tumour. It can be identified by injecting coloured dye and radioactive tracer into the region of the primary tumour, and then locating the specific draining lymph nodes which take up the dye and radioactivity. The sentinel node status is a powerful prognostic indicator in melanoma and is included within the most recent staging system for the tumour. The sentinel node technique is also being utilised in the management of other tumours, particularly breast cancer, in order to reduce the morbidity associated with total axillary lymph node removal. Other adverse prognostic factors include:

• ulceration

• vascular invasion

• lack of a host inflammatory response

• male gender

• high mitotic rate

• the presence of satellite lesions (cutaneous metastases) in adjacent skin.

Survival in malignant melanoma is improving as a result of greater public and medical awareness with earlier clinical presentation. Radial growth phase lesions have virtually 100% 5-year survival. When the Breslow thickness exceeds 1.5mm, 5-year survival drops to 34%.

Metastatic tumours

Deposits in the skin most frequently arise from:

• melanoma

• carcinoma (particularly breast, bronchus and large-intestine adenocarcinomas).

Cutaneous infiltration by lymphoma and leukaemia can also occur.

Self-assessment: questions

One best answer questions

2. A 29-year-old woman asks for advice about her risk of developing malignant melanoma, as one of her friends has just been diagnosed with this lesion. Which of the following are not of clinical relevance?

a. number of benign naevi (moles)

b. family history of skin cancer

c. cigarette smoking

d. fair hair colouring

e. history of childhood sunburn

True-false questions

1. Granulomatous inflammation is typically seen in:

a. tuberculosis

b. ulcerative colitis

c. erythema multiforme

d. foreign body reaction

e. sarcoidosis

2. In psoriasis:

a. the flexor surfaces are mainly affected

b. the epidermis shows regular thickening

c. epidermal turnover time is increased

d. nail changes are common

e. skin lesions consist of red plaques with silvery scale

3. The following are correctly paired:

a. Spongiosis – dermal oedema

b. Erythema multiforme – lichenoid inflammation

c. Xeroderma pigmentosum – squamous cell carcinoma

d. Pemphigoid – bullae formation

e. Dermatitis herpetiformis – granulomatous inflammation

4. In a pigmented lesion, the following clinical features are suggestive of malignant melanoma:

a. irregular border

b. uniform pigmentation

c. itching

d. changing size

e. bleeding

5. The following are risk factors for squamous cell carcinoma:

a. Bowen’s disease

b. chronic skin ulceration

c. psoriasis

d. actinic keratosis

e. irradiation

6. Regarding basal cell carcinoma:

a. 15% of tumours metastasise

b. it is commonest on the lower limbs

c. the microscopic growth pattern influences the risk of local recurrence

d. if left untreated, it can erode into underlying bone

e. it occurs exclusively in patients aged over 50

Case history questions

Case history 1

A 34-year-old man presents to his general practitioner (GP) with an enlarging lesion on his back which has recently bled. On examination there is a 7mm papule with variable pigmentation and an irregular border. The GP decides to perform an incisional biopsy for diagnosis. Histopathology shows an ulcerated vertical growth phase superficial spreading malignant melanoma, Breslow thickness 2.1mm, Clark level IV.

1. Is incisional biopsy appropriate for the initial diagnosis in this situation?

2. What do Breslow thickness and Clark level mean?

3. What does the histopathology report tell you about the likely behaviour of this tumour?

Case history 2

A 43-year-old woman presents to her GP with a linear vesicular rash around the left flank and back, which is painful. On examination, the GP also notes several warty growths on the hands, arms and neck. The patient underwent renal transplantation 2years earlier and is taking immunosuppressive drugs to prevent rejection of the transplanted kidney.

1. What is the likely cause of the rash?

2. Give the differential diagnosis for the warty growths.

Viva questions

1. What advice would you give to a group of healthy school children about skin cancer prevention?

2. Discuss the classification and complications of burns.

Self-assessment: answers

One best answer

2. c. Environmental risk factors for melanoma are clearly linked to UV exposure; pale-skinned individuals who burn easily in the sun are at highest risk. Although common benign naevi do not have an appreciable rate of transformation to malignant tumours, it does appear that individuals with large numbers of moles are at increased risk of melanoma, particularly if these moles are clinically or histologically atypical. A family history of melanoma also increases risk.

True-false answers

1.

a. True. Often with central caseous necrosis.

b. False. Granulomas are a feature of Crohn’s disease.

c. False.

d. True. Common foreign bodies may be exogenous, such as surgical sutures, or endogenous (liberated keratin from inflamed hair follicles or sebaceous cysts).

e. True.

2.

a. False. Extensor surfaces are typically involved.

b. True.

c. False. Cell turnover time is decreased.

d. True.

e. True.

3.

a. False. Spongiosis is intra-epidermal oedema.

b. True.

c. True. Xeroderma pigmentosum confers a greatly increased risk of all forms of skin cancer.

d. True.

e. False. Dermatitis herpetiformis is a vesico-bullous disease, which microscopically shows neutrophilic inflammation.

4.

a. True.

b. False. Uniform pigmentation can be seen in benign and malignant lesions.

c. True.

d. True.

e. True.

5.

a. True.

b. True.

c. False.

d. True.

e. e.True.

6.

a. False. The rate of metastasis is less than 1 in 1000.

b. False.

c. True.

d. True.

e. False. Although commonest in the elderly, basal cell carcinoma does occasionally occur in young adults, particularly white adults with a history of high sun exposure. Rare inherited skin disease syndromes can give rise to basal cell carcinoma in childhood.

Case history answers

Case history 1

1. As the clinical features here are very suspicious of melanoma, the lesion should initially be excised complete with a narrow margin rather than biopsied, to allow accurate histological diagnosis. If this confirms melanoma, a further wider excision of the surrounding skin will be required.

2. Comment: These are described in the text and Figure 71.

3. The tumour is in the vertical growth phase, and therefore there is a risk of lymph node and distant metastasis. The Breslow thickness of over 2mm is a poor prognostic factor as is ulceration. Statistically, male gender and lesion location on the back are also adverse features. This patient’s chance of being alive 5years from diagnosis is probably less than 50%.

Case history 2

1. This description of a painful, linear, vesicular rash arising in an immunosuppressed patient is virtually diagnostic of herpes zoster (‘shingles’). The patient may recall a previous episode of chicken pox, representing initial infection with varicella-zoster virus. The virus persists as a latent infection in dorsal root ganglia and may become reactivated at any time, but particularly with increasing age and in periods of ‘stress’ or reduced immune-system functioning. The virus travels via sensory nerves to the skin, where it replicates, causing the characteristic lesions.

Viva answers

1. Comment: Points to discuss include:

• the danger of episodic high sun exposure throughout life but particularly in childhood and young adulthood

• the rapidly increasing incidence of malignant melanoma, which is clearly linked to the increasing popularity of foreign holidays in hot places

• the need to apply appropriate sun protection products to exposed skin, and to reapply these regularly, especially before and after swimming, even on hazy days

• covering exposed skin with hats, sleeves, skirts, long trousers, etc.

• avoiding sun beds and tanning salons; the long-term reward of a manufactured ‘healthy’ tan is skin damage and tumour formation.

• You could also discuss the features of a changing mole that should prompt the patient to seek medical help; these are discussed in the text.

2. Comment: Burns are discussed in the text in Section 26.1.