69

Sexually Transmitted Diseases

In this chapter, five sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) are covered – syphilis, gonorrhea, chancroid, lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV), and granuloma inguinale. Additional more common STDs including herpes simplex infections, molluscum contagiosum, condyloma acuminata, crab lice, and HIV infection are discussed in Chapters 67, 68, 66, 71, and 65, respectively. When one STD is present, a search for others is indicated.

Syphilis (Lues)

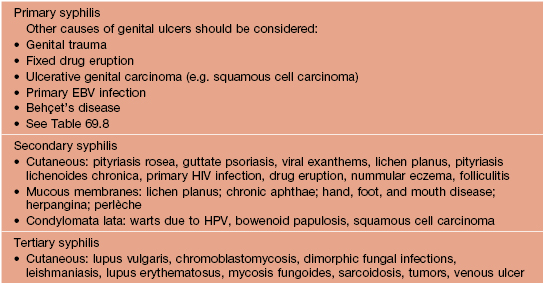

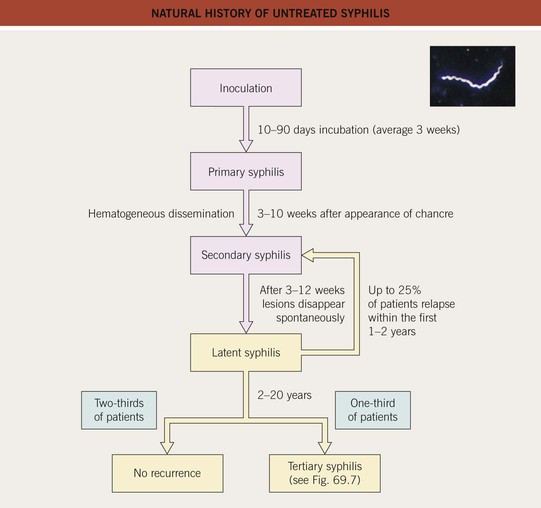

• Etiologic agent is the spirochete Treponema pallidum; the infection is divided into four phases: primary, secondary, latent, and tertiary (Fig. 69.1), in addition to a congenital form.

Fig. 69.1 Natural history of untreated syphilis. Chancres spontaneously resolve after a few weeks (see Fig. 69.3). In the group of patients with no recurrence, the rapid plasma reagin (RPR) becomes negative in 50% and remains positive in 50%. Adapted from Rein MF, Musher DM. Late syphilis. In: Rein MF (Ed.), Atlas of Infectious Diseases, Vol. V: Sexually Transmitted Diseases. New York: Current Medicine, 1995:10.1–10.13. Inset figure: Adapted from Morse SA, et al. Atlas of Sexually Transmitted Diseases and AIDS, 3rd ed. London: Mosby; 2003.

• One or more ulcers, usually anogenital, characterize primary syphilis and are referred to as chancres (Fig. 69.2); the ulcers are painless (unless secondarily infected) and upon palpation the base is firm; regional lymphadenopathy may be present (Fig. 69.3).

Fig. 69.2 Chancres of primary syphilis. The lesions are firm to palpation and are occasionally multiple. Sites of chancres include the penis (A, B), perianal area (C), and lip (D), as well as the fingers, cervix, and breast. A, C, D, Courtesy, Angelika Stary, MD.

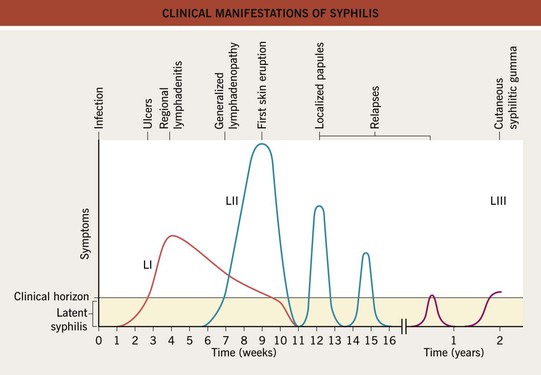

Fig. 69.3 Clinical manifestations of syphilis. LI, primary syphilis (lues); LII, secondary syphilis (lues); LIII, tertiary syphilis (lues). Adapted from Fritsch P, Zangerle R, Stary A. Venerologie. In: Fritsch P (Ed.), Dermatologie und Venerologie. Berlin: Springer, 1998:865–886.

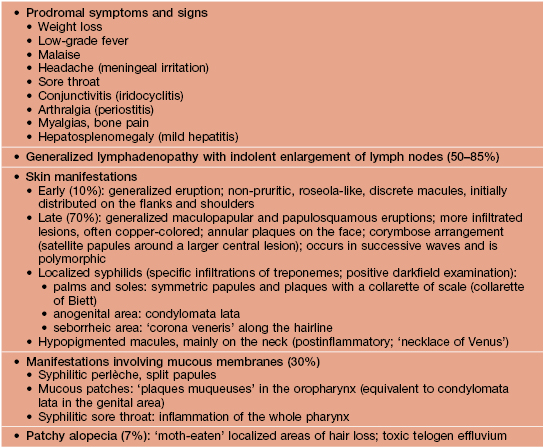

• Secondary syphilis reflects hematogenous dissemination and the skin lesions vary from macular to papulosquamous and from annular to granulomatous (Figs. 69.4 and 69.5); mucosal involvement is common and includes mucous patches, split papules at the angles of the mouth and condyloma lata (Fig. 69.6); usually accompanied by constitutional symptoms (Table 69.1).

Fig. 69.4 Secondary syphilis – cutaneous manifestations. Widespread exanthem of pink papules (A) and generalized papulosquamous lesions (B). Lesions on the palms (C) and soles (D, E) can have a collarette of scale; in patients with more darkly pigmented skin, these lesions may have a copper color. E, Courtesy, Angelika Stary, MD.

Fig. 69.5 Less common manifestations of secondary syphilis. A Annular plaques with central hyperpigmentation on the forehead. B Split papule at the oral commissure. C Granulomatous nodules and plaques. D ‘Malignant’ syphilis with multiple necrotic, ulcerated, and crusted lesions associated with severe constitutional symptoms. D, Courtesy, Angelika Stary, MD.

Fig. 69.6 Orogenital lesions of secondary syphilis. Oral lesions can vary from small superficial ulcers to mucous patches (A). Condylomata lata in the vulvar (B) and perianal (C) areas may be misdiagnosed as HPV infection (i.e. condylomata acuminata). C, Courtesy, Angelika Stary, MD.

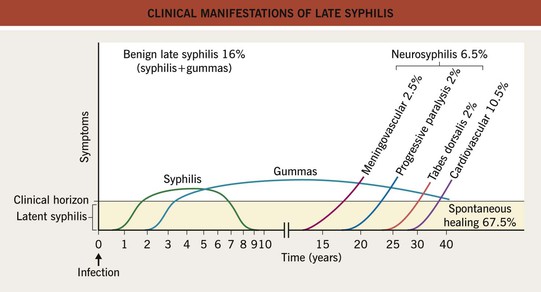

• Tertiary syphilis is preceded by a latent phase that can last for years (Fig. 69.7); the skin and mucous membranes, as well as the bones, develop gummas (Fig. 69.8), with cardiovascular syphilis and neurosyphilis representing the major causes of death in those who remain untreated.

Fig. 69.7 Clinical manifestations of late syphilis. Gummas occur most commonly in the skin (70%) and less often in the bones (10%) or mucous membranes (10%). In neurosyphilis, both endarteritis and direct invasion of the brain parenchyma can occur. Tabes dorsalis presents with painful paresthesias of the limbs, ataxia, and Argyll Robertson pupils. Adapted from Fritsch P, Zangerle R, Stary A. Venerologie. In: Fritsch P (Ed.), Dermatologie und Venerologie. Berlin: Springer, 1998:865–886.

Fig. 69.8 Cutaneous gummas of tertiary syphilis. Arciform, erythematous eroded plaques with central scarring.

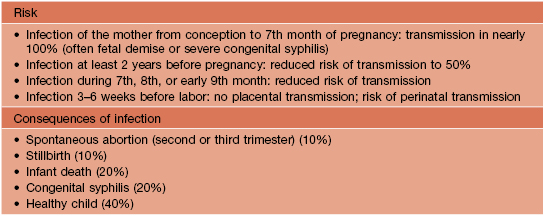

• In utero infection of a fetus can occur, primarily during the secondary or latent phases, leading to congenital syphilis or stigmata (Tables 69.2 and 69.3); the cutaneous lesions of early congenital syphilis are similar to those of secondary syphilis (Fig. 69.9), but they may be bullous; additional findings include a bloody or purulent nasal discharge (‘snuffles’), perioral and perianal fissures, and osteochondritis.

Table 69.2

Mother-to-child transmission of untreated syphilis and its consequences.

Courtesy, Angelika Stary, MD.

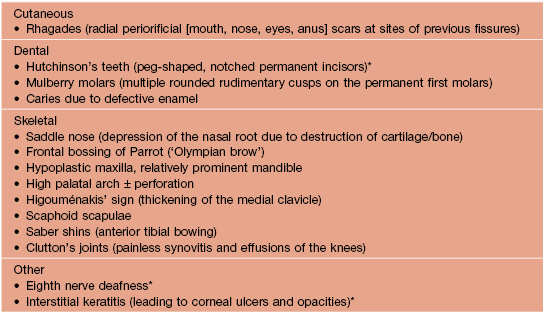

Table 69.3

Stigmata of congenital syphilis.

These findings represent the delayed consequences of inflammation at the sites of infection.

* Components of Hutchinson’s triad.

Courtesy, Angelika Stary, MD.

Fig. 69.9 Congenital syphilis. Red-brown plaques on the plantar surface, reminiscent of secondary syphilis in adults. Laboratory diagnosis includes identification of treponemes by darkfield microscopy and/or detection of 19S antibodies by the FTA-ABS-19S-IgM test (90% sensitivity) or spirochetemia by PCR.

• Rx: see Table 69.5 for treatment of primary, secondary, and early latent syphilis; patients with symptoms or signs suggesting neurologic disease should have CSF analysis and HIV-infected patients are at increased risk for neurosyphilis; for treatment of late latent, ocular, tertiary, and congenital syphilis as well as neurosyphilis, see www.cdc.gov/std/treatment or download the CDC STD Tx Guide App; a fourfold decrease in the antibody titer based on the RPR or VDRL assay is indicative of successful treatment.

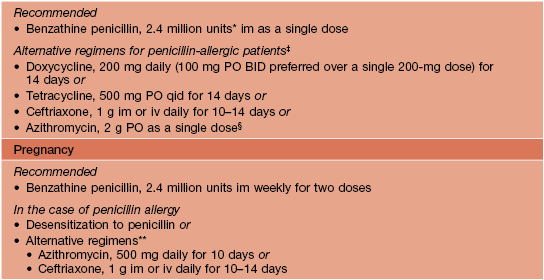

Table 69.5

Treatment recommendations for early syphilis (primary, secondary, and early latent [acquired <1 year previously]).

A Jarisch–Herxheimer reaction characterized by the acute onset of fever, headache, and myalgias can occur upon treatment of early syphilis. See the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines (http://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment) or download the CDC STD Tx Guide App.

* In children, 50 000 U/kg up to the adult dose.

‡ Limited data; desensitization to penicillin is recommended when compliance is an issue.

§ Resistance reported; not recommended in men who have sex with men and pregnant women.

** Limited data; not recommended by the CDC but included in the European Branch of the International Union against Sexually Transmitted Infections (IUSTI) guidelines.

BID, twice daily; h, hours; im, intramuscularly; iv, intravenously; PO, orally; qid, four times daily.

Gonorrhea

• While acute urethritis in men accompanied by a purulent discharge is the most common clinical presentation, the manifestations of gonorrhea are varied (Table 69.6); asymptomatic infections are common in women and when the rectum or pharynx is the site of infection.

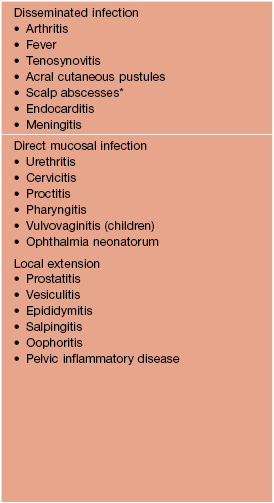

Table 69.6

Clinical manifestations of gonorrhea.

Both urethritis and cervicitis lead to a purulent discharge.

* In neonates at sites of fetal scalp monitor electrodes.

Courtesy, Angelika Stary, MD.

• In disseminated gonococcal infection, often referred to as the arthritis–dermatosis syndrome, a limited number of acral inflammatory pustules appear due to septic vasculitis, along with fever, arthralgia, and tenosynovitis (Fig. 69.10); risk factors include menstruation and deficiencies of the late components of complement (C5–C9; see Chapter 49).

Fig. 69.10 Gonococcemia (arthritis–dermatosis syndrome). Pustule with surrounding erythema on the toe. Courtesy, Angelika Stary, MD.

• DDx: for the urethral or cervical discharge, other infections, in particular due to Chlamydia trachomatis; for the cutaneous lesions due to gonococcemia, other infectious emboli, small vessel vasculitis, and neutrophilic dermatoses.

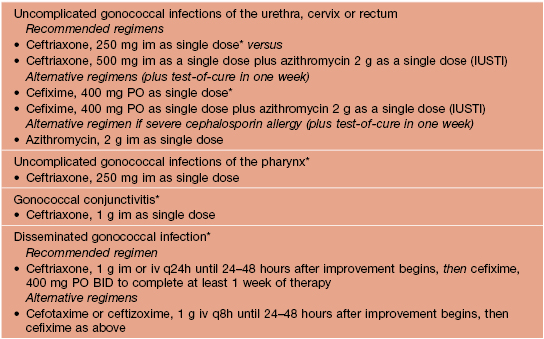

Table 69.7

Treatment recommendations for gonococcal infections.

Examination and treatment of sexual partners is also indicated. See the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines (http://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment) or download the CDC STD Tx Guide App.

* Additional treatment with azithromycin 1 g as single dose or doxycycline 100 mg BID for 7 days is recommended for all patients being treated for gonococcal infections; use of azithromycin is preferred.

BID, twice daily; h, hours; im, intramuscularly; iv, intravenously; PO, orally; q, every; IUSTI, European Branch of the International Union against Sexually Transmitted Infections guidelines.

Chancroid

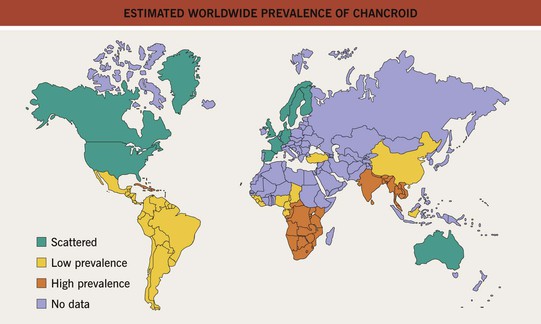

• The etiologic agent is Haemophilus ducreyi; this infection occurs more commonly in Africa and South Asia (Fig. 69.11), and it has a male : female ratio of 10 : 1.

Fig. 69.11 Estimated worldwide prevalence of chancroid. Adapted from Ronald A. Chancroid. In: Mandell GL (Ed.-in-Chief), Rein MF (Ed.), Atlas of Infectious Diseases: Vol. 5. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. New York: Current Medicine, 1995:16.1–10.

• After an incubation period of 3–10 days, painful genital ulcers, usually multiple, develop in conjunction with tender inguinal lymphadenitis (usually unilateral; Fig. 69.12); the base of the ulcer is purulent and soft, as opposed to the induration of syphilitic chancres.

Fig. 69.12 Chancroid. A Well-demarcated painful ulcers on the penis. B Multiple purulent ulcers with undermined borders. C Unilateral lymphadenitis with overlying erythema. B, Courtesy, Joyce Rico, MD.

• Dx: stained smears and culture (on special media) of ulcer exudate; PCR.

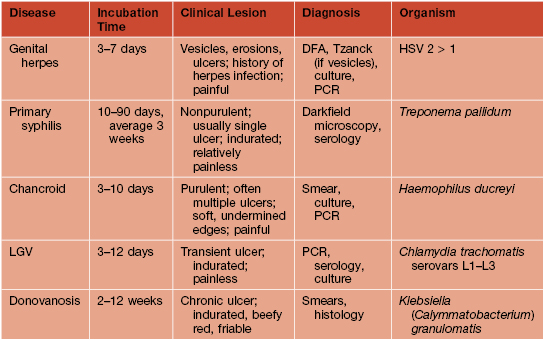

Table 69.8

Infectious causes of genital ulcer disease.

DFA, direct fluorescent assay; HSV, herpes simplex virus; LGV, lymphogranuloma venereum; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

Courtesy, Angelika Stary, MD.

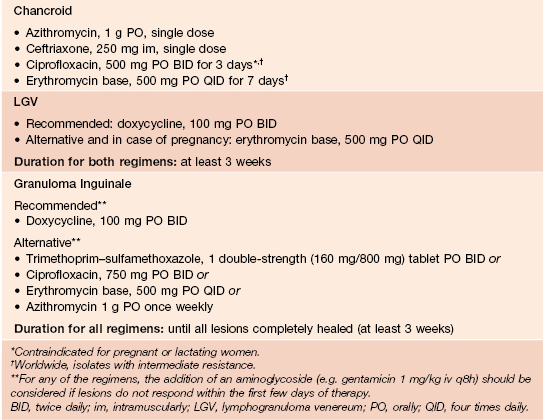

Table 69.9

Treatment regimens for chancroid, LGV, and granuloma inguinale.

Examination and treatment of sexual partners is also indicated.

Courtesy, Angelika Stary, MD.

Lymphogranuloma Venereum (LGV)

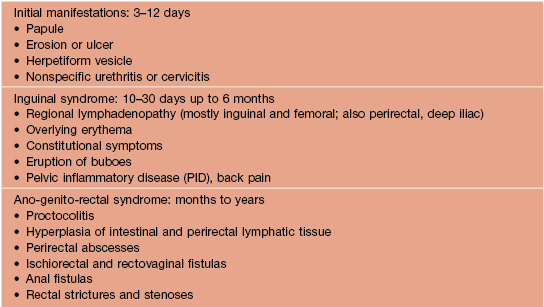

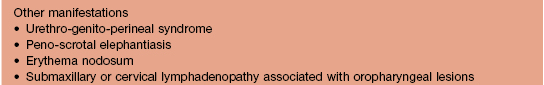

• Infection is acquired via the anogenital or rectal mucosa with subsequent lymphatic spread, leading to lymphadenopathy which is usually unilateral (Fig. 69.13); ~50% of patients develop a herpetiform lesion at the initial site of infection that heals spontaneously, following an incubation period of 3–12 days; the subsequent clinical manifestations are outlined in Table 69.10.

Fig. 69.13 Lymphogranuloma venereum. Inguinal bubo that has ruptured and drained. Courtesy, Angelika Stary, MD.

• Dx: detection of Chlamydia-specific DNA by PCR from affected tissues.

Granuloma Inguinale (Donovanosis)

• Clinically, an initial small papulonodule in the anogenital region ulcerates and then enlarges following an incubation period of up to 1 year (usually ~15–20 days); the base of the ulcer is often quite vascular with a foul-smelling drainage (Fig. 69.14).

Fig. 69.14 Granuloma inguinale (donovanosis). A Large ulcers with a characteristic ‘beefy’ appearance. B The vulva is the most common site of involvement in women with granulomatous plaques as well as ulcerations. A, Courtesy, Joyce Rico, MD; B, Courtesy, Francisco Bravo, MD.

• Dx: Detection of Donovan bodies in smears of tissue scrapings or touch preps of biopsy specimens (see Chapter 2).

For further information see Ch. 82. From Dermatology, Third Edition.