CHAPTER 25 Sexuality

25A. Sexual Development and Sexual Behavior Problems

Sexual behavior problems (SBPs) are deviations from typical sexual development and are defined as child-initiated behaviors that involve sexual body parts (i.e., genitals, anus, buttocks, or breasts) and are developmentally inappropriate or potentially harmful to themselves or others.1 Information about sexual development and guidelines for differentiating typical sexual behaviors from SBPs are rarely integrated in child development books or other types of parent educational materials. Thus, parents are often unsure how to determine whether sexual behaviors, such as interactions between children involving touching of genitals, are just “playing doctor” or something of concern. Parental guidance on sexual matters provided by developmental pediatricians facilitates caregiver’s education and decision making. Sexual behaviors occur on a continuum ranging from typical to problematic; therefore, to accurately identify and manage problems related to sexual behavior of children and youth, a good foundation in sexual development is necessary. Research on childhood SBPs is relatively new, although significant progress has been made since the 1980s in distinguishing typical development from SBPs, as well as in understanding the origins, trajectory, and treatment of SBPs in youth.

This chapter provides an overview of typical sexual development, knowledge, and behavior of preschoolers, school-aged children, and adolescents. To facilitate understanding of the terms and concepts, definitions of key variables are provided. SBPs are defined with information on origins of the behavior, developmental progression, assessment, and treatment outcome research for children and adolescents. Guidelines for distinguishing typical sexual behavior from SBPs are provided, as are references for parental education guidelines. Gender identity disorder is not discussed in this section; it is addressed in Chapters 25B and 25C.

We are not aware of another text designed specifically for developmental-behavioral pediatricians that covers both sexual development and the identification, assessment, treatment of, and response to SBPs across childhood and adolescence. A number of references provide pediatricians with information about typical sexual development and parental guidance suggestions, including provision of sex education.2–6 In addition, Horner provided a pediatric-focused brief review of sexual development and SBPs in children, including two case studies.7 The Association for the Treatment of Sexual Abusers (ATSA) Task Force on Children with Sexual Behavior Problems published a report on the identification, assessment, treatment, and public policies on children with SBPs, but this report does not address adolescence.8 Older reviews include an excellent book on sexually aggressive youth by Araji9; a chapter that also includes information on children with SBPs, adolescent sexual offenders, and adult sexual offenders10; and practice parameters provided by the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.11 Readers of these older reviews are advised to recognize that research published more recently updates previous assumptions, particularly regarding trajectory of the behaviors, long-term risk, and treatment outcome.

TERMINOLOGY

For this chapter, sex and gender are distinguished as follows: Sex is the classification by male or female reproductive organs,12 whereas gender is the behavioral, cultural, or psychological traits typically associated with one sex.13 Genitals refers specifically to external organs of the reproductive system, but references to “private parts” also include buttocks, anus, and breasts. Before specific information about how sexual knowledge and behavior evolve over the course of childhood and adolescents is provided, clarification in terminology would facilitate understanding of the research. In regard to knowledge about sexual matters, researchers have examined a wide range of children’s understanding of sex and sexual matters. Table 25A-1 lists the terms used in this chapter with their definitions.

TABLE 25A-1 Terms Used in This Chapter, Their Definitions, and Areas of Knowledge

| Term | Definition | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Term Used in This Chapter | ||

| Gender | Behavioral, cultural, or psychological traits typically associated with one sex | 13 |

| Sex | Classification by male or female reproductive organs | 12 |

| Genitals | The organs of the reproductive system; especially the external genital organs | 13 |

| Private parts or sexual body parts | Genitals, buttocks, anus, and breasts | |

| Sex role or gender role | The degree to which an individual acts out a stereotypical masculine or feminine role in everyday behavior | 157 |

| Sexual orientation | The inclination of an individual with regard to heterosexual, homosexual, and bisexual behavior | 13 |

| Sex preferences | Sex that children prefer to be like, to identify with, and to imitate in regard to sex role behavior | 16 |

| Childhood sexual behavior | Child-initiated behaviors involving sexual body parts (i.e., genitals, anus, buttocks, or breasts) | 1 |

| Sex play | Childhood sexual behavior that occurs spontaneously and intermittently, is mutual and noncoercive when it involves other children, and does not cause emotional distress | 1 |

| Sexual curiosity | Sexual behavior or questions about sexual matters motivated by inquisitive interest | |

| Sexual behavior problems in children and adolescents | Child and adolescents-initiated behaviors involving sexual body parts (i.e., genitals, anus, buttocks, or breasts) that are developmentally inappropriate or potentially harmful to themselves or others | 1 |

| Interpersonal or intrusive sexual behavior problems | Sexual behavior problems that involve two or more individuals and direct physical contact | 146 |

| Aggressive sexual behaviors | Sexual behavior problems that involve coercion, force, hostile intent, harm, or threatened harm | |

| Adolescent sexual offender | Adolescents between the ages of 13 and 17 years who commit illegal sexual behavior as defined by the sex crime statutes of the jurisdiction in which the offense occurred | 121 |

| Areas of Knowledge | ||

| Labels of female genitalia | Terms for female genitalia, such as vagina or a slang term | 18 |

| Labels of male genitalia | Terms for male genitalia, such as penis or slang term | 18 |

| Physiological distinctions between sexes | Understanding of the basic genitalia differences between sexes (i.e., boys/men have penises and girls/women have vaginas) rather than basing sex differences on other physical, behavioral, or character differences, often related to cultural gender distinctions (e.g., for white American children, beliefs that boys/men have short hair and girls/women have long hair) | 18 |

| Pregnancy and birth | Knowledge related to conception, roles of both father and mother in conception, intrauterine growth, and birth process (i.e., cesarean or vaginal delivery) | 18 |

| Adult sexual behavior | Behavior of adults related to intimate interactions, arousal, and/or stimulation of genitals, including kissing, masturbation, and sexual intercourse; not limited to procreation | 18 |

| Knowledge of sexual abuse | Conceptualizations of sexual abuse, abusers, victims, and consequences of abuse | 18 |

SEXUAL DEVELOPMENT

Early Childhood: Infants, Toddlers, and Preschoolers (Aged 0 to 6 years)

PHYSICAL DEVELOPMENT

Even as infants, children are capable of sexual arousal; newborn boys have penile erections, and baby girls are capable of vaginal lubrication.14–16 Otherwise, until puberty, there is limited change in physical sexual development (including hormonal and gonad changes) during early childhood.3

SEXUAL KNOWLEDGE

Children as young as 3 years of age can identify their own sex and, soon after, identify the sex of others.17,18 Initially distinctions between the sexes are based on visual factors found in the culture (such as hair), although by age 3 or 4 years, many children are aware of genital differences.18,19 Both girls and boys have been found to be more likely to know labels of male than of female genitalia.20–22

Much of the research on sexual knowledge of preschool children was conducted before 1997.19,20,23–26 Interestingly, the same pattern of results for toddlers and preschoolers have been found in a more recent study on knowledge of genital differences, pregnancy, birth, procreation, sexual activities, and sexual abuse.18 Preschool children’s understanding of pregnancy and birth tends to be vague until age 6, when most report knowledge of intrauterine growth, a third know about the concept of fertilization, and most know about birth by cesarean or vaginal delivery. Knowledge of adult sexual behavior was most often limited to behaviors such as kissing and cuddling; only 9% of 3-year-olds mention explicit sexual behaviors, increasing to 21% for the 6-year-olds, and another 8% of 6-year-olds can give detailed descriptions of the acts. The rate of this behavior is affected by abuse: Sexually abused 2- to 5-year-olds have been found to talk more about sex than do preschool-aged children in normative samples of (33% and 2%, respectively).27

SEXUAL BEHAVIOR

Preschool-aged children are curious in general and tend to actively learn about the world through listening, looking, touching, and imitating. Children as young as 7 months have been found to touch and play with their own genitalia; this behavior is found in both sexes but is more common in boys.15,16 Infants’ and young children’s self-touch appear largely related to curiosity and pleasure seeking.3 Children aged 2 to 5 years look at others when they are nude, intrude on others’ physical boundaries (e.g., stand too close to others), touch their own genitalia even in public, and touch women’s breasts (occurring in at least 25% of normative samples27,28). Preschool-aged children’s general curiosity about the world manifests with questions and exploratory and imitative behaviors concerning sexual body parts.3 Although gender role behavior is seen as early as age 1, dressing like the opposite sex is also not unusual throughout this developmental period (14% of boys and 10% of girls).27,28 Boys demonstrate strong same-sex preferences early in the preschool years that increase in strength over time, whereas girls’ same-sex preferences, strong in the preschool years, wanes in later years.16

Nonintrusive sexual play of showing sex parts to other children was found in 9% of preschoolers, and 4.5% were reported to have touched another child’s sexual body parts (reported by mothers).27 Sexual play is discussed in more details in the next section. Culture and social context affects the incidence of these typical behaviors, inasmuch as frequencies of these behaviors have been found to differ by the population and the situation studied.29–32 Cultural effects are described in more detail later in this chapter.

Intrusive (putting finger or objects in another child’s vagina or rectum), planned, and aggressive sexual acts were not reported by anyone in a normative sample of mothers of preschool children.33 Other rare behaviors include putting objects in vagina/rectum, putting the mouth on sexual body parts, and pretending toys are having sex.29,27,32

School-Aged Children (Aged 7 to 12 Years)

PHYSICAL DEVELOPMENT

Pubertal development on average begins around 10 years of age, with girls starting earlier then boys, and can begin as early as 7 or 8 years of age. For girls, early puberty starts with a growth spurt in height, followed by a growth spurt in weight. Boys’ growth spurts are often later than girls,2 and occurs with acceleration of the growth of the testes and scrotum, enlargement of the larynx, and deepening of the voice.16 There is wide variation, affected by a variety of factors (e.g., nutrition, heredity, race), in the onset and course of puberty, including a 4- to 5-year age range for the onset of puberty.16 This variability can have significant effects on social adjustment of youth. Further information about puberty is provided later in the section on adolescent sexual development.

SEXUAL KNOWLEDGE

Knowledge of pregnancy, birth, and adult sexual activity increases during the school-age period. By age 10, most children have basic and more realistic understanding of puberty, reproductive processes, and birth.3 Accuracy of knowledge depends in part on the child’s exposure to correct informal and formal educational material.

SEXUAL BEHAVIOR

School-age children’s behaviors become more guided by societal rules, which restrict the types of sexual behavior demonstrated in public. Sexual behavior continues to occur throughout the school-age period, but it is more concealed, and thus caregivers may not be directly aware of the behavior. In contrast to younger children, school-aged children are much less likely to touch their private parts in public or women’s breasts.27 However, they are more interested in media and are more likely to seek out television and pictures that include nudity.27 Masturbatory behaviors occur, with an increase in frequency in boys during this developmental period.16 Modesty emerges during this developmental period, particularly in girls, who become more shy and private about undressing and hygiene activities.34

During the early school years, children tend to seek out and interact with children of the same sex.35 Interest in the opposite sex increases near the end of this developmental period with puberty, and interactive behaviors initiates with playful teasing of others. A small but substantial portion is involved in more explicit sexual activity, including sexual intercourse, at the end of this developmental period.36

SEXUAL PLAY

Sexual play is distinguished from problematic behaviors in that childhood sexual play involves behaviors that occur spontaneously and intermittently, are mutual and noncoercive when they involve other children, and do not cause emotional distress.1,8 Sexual play typically occurs among children of similar age and ability who know and play with each other, rather than between strangers. Interpersonal sexual play often occurs between children of the same sex and can include siblings.16,37,38 Experiencing sexual play at least once during childhood appears prevalent (reported by more than 66% to 80% of adults in retrospective research) and can occur in children as young as 2 or 3 years. Many incidents of sexual play in school-aged children may be unknown by caregivers, because the behaviors are more likely to be hidden with increased awareness of social norms.37–39 Some degree of behavior focused on sexual body parts, curiosity about sexual behavior, and interest in sexual stimulation are a normal part of child development. This type of exploratory sexual play (periodic and without coercion or force and between children of similar age/abilities) has not been found to negatively affect long-term adjustment,37,40–42 although inconsistent results have been found with sibling involvement.43

Childhood sexual play and exploration are not a preoccupation and usually do not involve advanced sexual behaviors such as intercourse or oral sex. Intrusive, planned, coerced, and aggressive sexual acts are not part of typical or normative sexual play of school-aged children; rather, they are perceived as problematic.33 SBPs are discussed more extensively later in the chapter.

Adolescent Sexual Development (Ages 13 to 19 Years)

PHYSIOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENT

During adolescence, changes associated with puberty continue, including enlargement and maturation of the genitalia and secondary sex characteristics.44 Most girls by age 16 have begun to menstruate; the average age at onset is 12 years.3,45,46 Current research indicates that Caucasian girls enter puberty approximately 1 year earlier and African-American girls approximately 2 years earlier than previous studies have shown. The mean age for the beginning of breast development (sexual maturation rating stage 2) in African-American girls has been found to be 8.87 years, and that for white girls, 9.96 years.47 By age 15, most boys are capable of ejaculation.3 About 2 years after pubic hair growth begins, there is development of axillary and facial hair, as well as an acceleration of muscular strength. Hormonal changes that occur during puberty affect sexual interest, behavior, and fantasies.48–50

SEXUAL KNOWLEDGE AND BEHAVIOR

It is expected that adolescents have knowledge about sexual intercourse, contraception, and sexually transmitted diseases.3 However, the quality of the knowledge they possess varies greatly across individuals. Evaluations of a variety of sex education programs (e.g., sex education, human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] education, teen pregnancy prevention) targeted at adolescents suggest that such programs do not lead to earlier onset of sex, more frequent sex, or more sexual partners. Many programs have been found to be associated with better outcomes for youths, including delay in the onset of sexual intercourse, increase in the use of contraceptives, and reduction in the number of sex partners. Programs more likely to affect teenagers’ behavior contain several common characteristics, including having and reinforcing messages about abstinence and/or use of contraception, focusing on reducing at least one sexual behavior that leads to pregnancy or HIV infection and sexually transmitted diseases, and providing information about the risks of adolescent sexual activity.51,52

Many studies indicate that increases in sexual behavior during adolescence are not only influenced by hormones but are also affected by social factors, including parental supervision, peer influences, and community characteristics.53–55 Several factors have been identified as being associated with the onset of sexual activity in adolescents: (1) less educated mothers; (2) having a boyfriend or girlfriend; (3) lower educational expectations (i.e., no intention of going to college); (4) authoritarian parenting; (5) poor communication with parents about sexuality; and (6) older siblings who are sexually active.45

The majority of teenagers engage in some form of sexual activity, whether masturbation or sexual intercourse. Studies have shown that 25% to 40% of adolescent girls and 45% to 90% of adolescent boys masturbate with or without sex toys like dildos.49,56 Sexual activity rates in adolescents have increased more than 79% since 1970.57 In 2003, 47% of students in grades 9 to 12 reported that they had had sexual intercourse. Of these high school students, 14% reported having had sexual intercourse with four or more partners.58 Research studies have revealed that 10% to 49% of adolescents have engaged in oral-genital contact, and the incidence is increasing.59–61 Sexual experimentation and exploration is normative and may include behaviors with same-sex peers.

Risks associated with increased and early-onset sexual activity are notable, including sexually transmitted diseases, pregnancy, substance use, and exposure to and experiences of assault and unwanted sexual experiences. Although condom use has increased, it is not consistent, and approximately 25% of sexually active youths have been found to contract sexually transmitted diseases each year.36 Furthermore, use of substances before sexual activity has increased.62 Youths are at risk for experiences of sexual assault, force, coercion, and violence.2 Other youths are often the offenders in these assaults, and information about management of adolescent sexual offenders is provided later in the chapter.

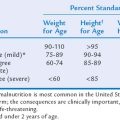

A summary of sexual development information by age group is provided in Table 25A-2.

TABLE 25A-2 Sexual Development by Age

| Development Description | Reference |

|---|---|

| Neonatal Period and Infancy | |

| Boys may have penile erections, and girls are capable of vaginal lubrication. | 14, 15 |

| Babies as young as 7 months touch their own genitalia. | 15 |

| Preschool Years (Ages 3-6 Years) | |

| Most 3-year-olds’ knowledge of adult sexual behavior is limited to kissing and cuddling, and approximately 30% of 6-year-olds know about more explicit sexual acts. | 18, 27 |

| Children identify their own sex and sex of others, initially differentiating sexes by external characteristics (e.g., hair). | 18 |

| Children are aware of genital differences of the sexes by the end of this developmental period. | 18, 19 |

| Their understanding of pregnancy and birth tends to be vague. | 18 |

| They often have questions about, as well as exploratory and imitative behaviors concerning, sexual body parts. | 3 |

| They have a vague understanding of pregnancy and birth, with some knowledge of intrauterine growth and birth by cesarean or vaginal delivery by the end of this developmental period. | 18 |

| Nudity, looking at other people’s bodies (particularly during hygiene activities), dressing like the opposite sex, and non intrusive sex play are not unusual. | 27, 28 |

| School Years (Ages 7-12 Years) | |

| Children tend to seek out and interact with same-sex children. | 3 |

| Girls become more shy and private about undressing and hygiene activities. | 34 |

| Children have a basic understanding of puberty, reproductive processes, and birth. | 3 |

| Pubertal development begins, with girls starting before boys. | 2 |

| Breast development begins in girls. | 47 |

| There is a wide variation in the onset and course of puberty. | 16 |

| Sexual behavior, including sexual play, occurs but is more likely to be concealed than during preschool years. | 3 |

| Sexual play typically occurs with children with whom they are interacting, including other children of the same sex and siblings. | 16, 37, 38 |

| Sexual play (periodic and without coercion or force and between children of similar age/abilities) has not been found to negatively affect long-term adjustment. | 37, 41 |

| Masturbatory behavior increases during this developmental period, particularly in boys. | 16 |

| Interest in the opposite sex increases with the onset of puberty. | 35 |

| Adolescence (Ages 13-17 Years) | |

| Enlargement and maturation of the genitalia and secondary sex characteristics occur. | 44 |

| Most boys by age 15 are capable of ejaculation. | 3 |

| Most girls by age 16 have begun to menstruate. | 3, 45 |

| Knowledge about sexual intercourse, contraception, and sexually transmitted diseases varies greatly across individuals. | 3 |

| Majority of adolescents engage in some form of sexual activity, whether masturbation, oral-genital contact, or sexual intercourse. | 49, 56, 58–61 |

| Experimentation and exploration of a range of sexual behaviors, including sexual behavior with the same and opposite sex, occurs. | 2, 49 |

SPECIAL TOPICS ON SEXUAL DEVELOPMENT: CULTURAL FACTORS, SEXUAL ORIENTATION, DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES, AND SEXUAL ABUSE

Cultural Factors Affecting Sexual Development and Behavior

Children’s public and private sexual behavior, modesty, intimacy, and relationships are affected by their family’s and communities’ cultural values, beliefs, norms, religion, spirituality, socioeconomic, historical, and other factors. For example, social environments with norms in which nudity is acceptable, privacy is not reinforced, and exposure to sexualized material is common have been found to be related to higher frequencies of sexual behaviors in the children than are social environments that reinforce modesty and privacy.28

Parents’ attitudes toward children’s sexuality have been found to affect children’s sexual knowledge and behavior.19 Cultural beliefs may explain normative differences found in cross-cultural studies. For example, mothers of Dutch children report greater frequencies of sexual behaviors in their preschool-aged children than do mothers of American children, which may be related to a more permissive, positive attitude about sexuality and nudity in The Netherlands than in the United States.30 Cultural differences in children’s sexual knowledge (such as physiological distinctions between sexes, pregnancy, and birth) have also been found. For example, preschool-aged girls in the Western hemisphere have been found to perceive that babies were always in their mother’s bellies, whereas Asian boys thought the baby was swallowed.16

Factors may interact, and differences in regard to norms between boys and girls are not uncommon. Implicit and explicit messages about sexual behavior are provided to children and youths through family, friends, neighbors, and the community, as well as a variety of media (including television, movies, music videos, music lyrics, video games, magazines, the Internet, and communications with cell phones). How children sort out the multiple and often conflicting messages about sex, sexuality, and relationships are not clearly understood. However, reduced risk-related behaviors have been found with attentive parenting with close supervision and good communication. Entertainment television can also have a positive effect on youth knowledge, particularly when paired with good communication with parents.63 Ways in which culture may affect educational and intervention approaches are discussed later in the section on intervention.

Homosexuality

Homosexuality does not begin during adolescence. However, adolescence is the most likely time during childhood that concerns about sexuality, sexual orientation, and sexual behavior are presented to the developmental-behavioral pediatrician.

Many youths experiment with and explore a range of sexual behaviors, including sexual behavior with people of the same and opposite sex.2,49 Sexual exploration and behavior are not synonymous with sexual orientation.64 With whom youths have sexual behavior may be more strongly related to who is regularly in their social environment than with sexual orientation. Adolescents with homosexual experiences may identify themselves as having a heterosexual orientation. Furthermore, adolescents with no sexual experience or only heterosexual experiences may identify themselves as homosexual or bisexual.49

National data suggest that 2.3% of men and 1.3% of women in the United States are self-identified as homosexual.60 In the same survey, 1.8% of men and 2.8% of women described themselves as bisexual.60 Accurate prevalence rates are difficult to calculate because of the continuing stigmatization of homosexuality.64 In a survey of junior and high school students from Minnesota, approximately 88% self-identified as heterosexual, 1.6% of boys and 0.9% of girls identified themselves as either primarily homosexual or bisexual, and more than 10% were “not sure” of their sexual orientation.65 More information on homosexuality and development is available in Chapter 25C.

Children and Adolescents with Developmental Delays and Disabilities

Sexual development can be more variable when children and youth have developmental delays or disabilities or chronic medical conditions. Developmental disabilities and medical conditions may be associated with precocious or early-onset puberty (e.g., Down syndrome, traumatic brain injuries, and tumors, including hamartoma), delayed puberty (e.g., Prader-Willi syndrome), or disrupted sexual development (e.g., spinal cord injuries).3,66,67 Historically, professionals and family members have inadequately understood, accepted, and responded to sexual development in individuals with disabilities.3,67 However, as in all children, sexual arousal and sexual behaviors begins at or around birth, pubertal development with the associated sexual feelings typically occurs, and many adolescents with developmental disabilities date and are sexually active.68 Unfortunately, many youths with developmental disabilities have not been provided developmentally appropriate sexual education.67,69 Providing sex education for children with developmental delays is discussed in the section on recommendations concerning clinical care later in this chapter.

Effect of Sexual Abuse on Childhood Sexual Knowledge and Behavior

Sexual abuse affects children’s sexual knowledge, as well as their sexual behavior. Furthermore, sexually abused children have been found to have greater frequencies of a wide range of sexual behaviors in comparison with normative samples and with children who were clinically referred with no known history of sexual abuse.28,70,71 Sexually abused preschool-aged children are at greater risk for inappropriate sexual behaviors (35%) than are sexually abused school-aged children (6%).70

Although most sexually abused children do not demonstrate SBPs, the presence of SBPs raises concern about child sexual abuse and exposure to sexual material. Professionals need to be well aware of the child abuse reporting statutes in their jurisdiction, because reports of suspected sexual abuse may be necessary. Specific sexual behaviors (such as playing with dolls imitating explicit sexual acts and inserting objects in their own vaginas or rectums) are more likely to occur in children who have been sexually abused than in those who do not have a suspected history.27,30,72 The presence of sexual behavior maybe enough to suspect sexual abuse and report to authorities for investigation; however, sexual behavior itself cannot be a sole determining factor for diagnosing sexual abuse.8 Confirming sexual abuse in young children is quite complex, because often there is no physical evidence and no witnesses, and aspects of the abuse (e.g., threats by the perpetrator) hamper clear reporting by the child.73 Additional information on identification and reporting of and response to suspected sexual abuse is provided in The APSAC Handbook on Child Maltreatment (2ed) by Myers JEB, Berliner L, Briere J et al, 2002.

SEXUAL BEHAVIOR PROBLEMS

Not all sexual behavior among youth is normative or appropriate. In the following discussion, SBPs in youth are defined, with information about the prevalence, origins, and trajectory of SBPs, as well as current findings on assessment, treatment, and management. Because of developmental and legal distinctions, children with SBPs are discussed separately from adolescents.

Problematic Sexual Behavior during Childhood (Ages 3 to 12 Years)

Sexual behavior in childhood occurs on a continuum from typical to concerning to problematic.74 SBPs do not represent a medical/psychological syndrome or a specific diagnosable disorder; rather, they represent a set of behaviors that are well outside acceptable societal limits.8 SBPs in this context are defined as child-initiated behaviors that involve sexual body parts (i.e., genitals, anus, buttocks, or breasts) and are developmentally inappropriate or potentially harmful to themselves or others.1 SBPs may range from problematic self-stimulation (causing physical harm or damage) to nonintrusive behaviors (such as preoccupation with nudity, looking at others) to sexual interactions with other children that include behaviors more explicit than sexual play (such as intercourse) to coercive or aggressive sexual behaviors (of most concern, particularly when paired with large age differences between children).

Although the term sexual is used, the intentions and motivations for these behaviors may not be related to sexual gratification or sexual stimulation. Rather, the behaviors may be related to curiosity, anxiety, reenacting trauma, imitation, attention-seeking, self-calming, or other reasons.1

Children as young as 3 and 4 years of age with SBPs have been described in the literature.75–78 Girls may be somewhat more likely than boys to be referred for services for SBPs during preschool years78 and boys during the school years.79,80 However, no population-based statistics on the incidence or prevalence of SBPs in children are available. By definition, most of the sexual behaviors involved are fairly rare.28 Since the 1980s, there has been an increase in the number of children with SBPs who have been referred for child protective services, juvenile services, and treatment in both outpatient and inpatient settings.81 The increase in referrals may represent an actual increase incidence of such behaviors, changing definitions of problematic sexual behavior, improved awareness and reporting of what has always existed, or some combination of these factors.8

The prevalence of sexual behavior for specific races, ethnic groups, religious groups, and socioeconomic groups is unknown. In groups in which there are extremely high rates of sexual abuse at a young age, the children are at higher risk for developing problematic sexual behaviors.

ORIGINS OF SEXUAL BEHAVIOR PROBLEMS IN CHILDREN

Social context, individual characteristics, disruptive experiences, and the interactions of these factors affect the course of sexual development.9 Sexual abuse is one type of disruptive experience affecting sexual development. Children, particularly preschool age children,70 who have been sexually abused are more likely to demonstrate SBPs than are children without such a history.28 However, many children with SBPs have no known history of sexual abuse.76,78,79,82 The development of SBPs appears to have multiple origins, including exposure to family violence, physical abuse, parenting practices, exposure to sexual material, absence of or disruption in attachments, heredity, and the development of other disruptive behavior problems.33,83–85 For some children, SBPs may be one part of an overall pattern of disruptive behavior problems,83,86,87 rather than an isolated or specialized behavioral disturbance.

RISKS AND COMORBIDITY OF SEXUAL BEHAVIOR PROBLEMS

Regardless of the causal pathway, a young child’s demonstration of SBPs is associated with a variety of negative consequences in adjustment and development. Trauma histories and related trauma symptoms are common, particularly in young children with SBPs.78,87 Children with SBPs often exhibit other behavior problems and disruptive behavior disorders.78,79,84,87,88 Poor impulse-control skills, aggressive behaviors, and inaccurate perceptions of social stimuli hinder social relationships and cause problems at school.9,79,88–90 Socialization difficulties and stigmatizing responses from peers and adults may impede developing self-concepts.91 Poor boundaries and indiscriminate friendliness may increase risk of future victimization.78,92 Furthermore, children with SBPs are at risk of separation from parents and of placement disruptions.78,79,93,94

CLASSIFICATION

There is much to be learned about subtypes of SBPs, because the research in this area is limited to a few studies. Youths with more frequent and more intrusive SBPs are more likely to have other behavior and emotional problems, to have caregivers with histories of trauma, and to have learning difficulties than are children with less frequent or nonintrusive sexual behaviors.95,96 Typological examinations of comorbidity have suggested the differential effects of trauma and disruptive behavior, as well as gender’s effect on rate of sexual behaviors.87 Otherwise, how types of SBPs affect the functioning of the children demonstrating the behavior, the trajectory of SBPs and related concerns, and responsiveness to interventions are unknown.

EFFECT OF SEXUAL BEHAVIOR PROBLEMS ON OTHER CHILDREN

When children experience sexual behaviors initiated by other children, there can be a range of effects. The literature is scant but appears to suggest that sexual behaviors between children of similar age and ability that was of mutual agreement and without intrusive or aggressive behaviors is retrospectively viewed as neutral or positive. However, when the sexual behavior experienced is considered to be an SBP as previously defined, the experience can have potentially negative effects, perhaps similar to those of sexual abuse perpetrated by adolescents or adults. The research on the effect of child sexual abuse indicates that the level and severity of the effect are influenced by the duration; frequency; relationship with the initiator of the sexual acts; use of aggression, coercion, or force; the child’s previous functioning; and the response and support by the caregivers.97 Response can range from no or limited discernible symptoms to the development of trauma symptoms, other internalizing symptoms, behavior problems, sexual behaviors themselves, and/or social and peer problems.

ASSESSMENT OF SEXUAL BEHAVIOR PROBLEMS (AGES 3 TO 12 YEARS)

When caregivers report concern about the sexual behavior of children, an initial screening can facilitate the need for further clinical assessment. Gathering information about the type, frequency, duration, level of intrusiveness, harm, use of coercion, and course of behaviors can facilitate distinguishing typical from problematic sexual behaviors. The Child Sexual Behavior Inventory (CSBI)27 is the only norm-based parental report measure of child sexual behavior with gender and age norms for ages 2 to 12 years. It is a 38-item measure used to assess boundary issues, showing of private parts, self-stimulation, sexual anxiety, sexual interest, sexual knowledge, interpersonal and intrusive sexual behavior, and looking at others’ private parts. It is easy to administer and score; the Total Scale Score provides a T-score and a percentile that are based on age and gender norms. The published manual recommends that the CSBI be administered by mental health professionals with training in psychological assessments. It is important to note that this published version does not include any items concerning sexual aggression. Friedrich33 evaluated four such items and found none of them to be endorsed by mothers in a normative sample. Friedrich also provided a checklist to assess exposure to sexualized material, supervision, and privacy, which facilitates developing a safety plan with the family.33

Assessment of the situations or circumstances under which SBPs seem to occur, the social ecology, exposure to sexualized materials, and success of attempts made to correct the behaviors can guide identifying points of intervention and treatment recommendations. The Child Sexual Behavior Checklist, 2nd revision, can help assess contributing factors and identify environmental intervention area, as it lists 150 behaviors related to sex and sexuality in children, asks about environmental issues that can increase problematic sexual behaviors in children, gathers details of children’s sexual behaviors with other children, and lists 26 problematic characteristics of children’s sexual behaviors.98 However, the no norms have been published for the Child Sexual Behavior Checklist.

Comorbid disruptive behavior disorders, affective disorders, trauma-related symptoms, and learning deficits are not uncommon in children with SBPs.78–80,84,87 Thus, a broad assessment is warranted and may include such measures as the Child Behavior Checklist (which includes items on sexual behavior),99,100 or the Behavior Assessment System for Children.101 To specifically assess trauma symptoms, the Trauma Symptom Checklist for Children (child report) and the Trauma Symptom Checklist for Young Children (caregiver report) are useful instruments that include subscales related to sexual concerns.102,103 For preschool children, the Weekly Behavior Report104 is useful in assessing a wide range of emotional and behavior problems, including SBPs, and in tracking progress over time.

A common misunderstanding is that if a child has SBPs, he or she must have a history of sexual victimization. Although a history of previous or ongoing sexual abuse increases the risk for developing SBPs,70,72 there appear to be multiple pathways to the development of SBPs, and the presence of SBPs should not be presumed sufficient evidence of sexual abuse. However, when a child exhibits SBPs, it is appropriate for assessors to make direct inquiries into whether the child has been or is being sexually abused.8 Suspected sexual abuse that had not been previously investigated by Child Protective Services necessitates responses consistent with state and regional child abuse reporting statutes. Additional information on management of suspected child sexual abuse is available in The APSAC Handbook on Child Maltreatment (2ed) by Myers JEB, Berliner L, Briere J, et al, 2002.

CASE EXAMPLE

A description of the application of these measures and assessment procedures to a case may facilitate application of the information. An example case of a young child follows:

Jill Doe is a 6-year-old girl who was referred by Child Protective Services after their investigation into possible sexual abuse. Their investigation was inconclusive. There were continued concerns regarding her sexual behaviors. Jill lives with her father and 3-year-old sister. She has sporadic visitations with her mother, who has a substance abuse problem. Jill’s father provided the history of sexual behavior, in which he reported that Jill was found on top of a 4-year-old girl, kissing her and touching her genital area over the clothes. This behavior was followed by observing her embracing and kissing two different young boys at a local park. A couple of months ago, she was found to be making her dolls “have sex,” upon which her father responded by taking the dolls away. Around that time, she also found Jill visually examining her 3-year-old sister’s vaginal area and touching their dog’s private parts. All of these sexual behaviors have continued despite the father’s efforts to stop the behaviors through distraction, removal of toys, and punishment (grounding). In addition to these sexual behaviors, Jill’s father expressed concern about Jill’s sleep problems, nightmares, moodiness, and temper tantrums.

Jill’s father completed the CSBI and Child Behavior Checklist. On the CSBI, he endorsed items reflecting the sexual behaviors noted previously and the Total Standard Score of 23, which falls at the T-score of 108, in the clinical range. Thus, the sexual behaviors Jill has been exhibiting according to her father’s report are much greater in frequency than those of the normative sample of girls her age. Problems were noted in regard to boundaries and interpersonal sexual behavior problems. The Safety Checklist suggested that Jill has been exposed to sexualized materials while in her mother’s care. Furthermore, she often sleeps and bathes with her sister and, at times, her cousins. Jill was reported to have been exposed to violence and substance use. The Child Behavior Checklist scores were 68 for Total Problems, 67 for Externalizing Problems, and 65 for Internalizing Problems. The Weekly Behavior Report indicated that Jill is exhibiting sexual behavior problems a couple of times a week, as well is experiencing nightmares and temper tantrums four times a week. Services for sexual behavior problems and integrating strategies to address behavior problems, nightmares, and abuse prevention skills appear warranted. Work with the caregivers regarding privacy rules, boundaries, and protection from trauma and stress is also indicated. The Weekly Behavior Report measure is brief enough that frequent administration is not burdensome and can track treatment progress.

TREATMENT FOR SEXUAL BEHAVIOR PROBLEMS (AGES 3 TO 12 YEARS)

SBPs have been successfully treated with SBP-specific therapy services for school-age children and preschool children.8,79,105,106 Further, Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavior Therapy as a treatment for the effects child sexual abuse that includes SBP-specific elements effectively reduces SBPs in sexually abused preschool-aged children.107–110 These treatments have been found to be more effective than time (wait periods), play therapy, and nondirective supportive treatment approaches. The types of SBPs found in the children involved in the studies have been wide ranging, with most children demonstrating interpersonal sexual behaviors, and include aggressive sexual behaviors.

One study provided results from a 10-year follow-up on children with SBPs who had been randomly assigned to receive group cognitive-behavioral treatment (CBT) or group play therapy. The study included a clinic comparison group of children with disruptive behavior problems but no SBPs.105 Child welfare, juvenile justice, and criminal administrative data on all the children were collected and were aggregated. The CBT recipients were found to have had significantly fewer future sex offenses than the play therapy recipients (2% vs. 10%) and did not differ from the general clinic comparison (3%).105 The overall rate of future sexual offenses not only was quite low with short-term outpatient CBT that involved families but also was indistinguishable from that of the comparison sample.

Common elements of the effective treatments are outpatient, short-term, cognitive-behavioral and educational approaches; caregiver direct involvement; teaching of rules about sexual behaviors and skills to facilitate maintaining these rules (such as feeling identification, impulse control, and problem-solving skills); sex education; and teaching caregivers efficacious behavior management strategies (such as praise, reinforcement, timeout, and logical consequences). This treatment should be distinguished from CBT approaches to treating adolescent and adult sexual offenders. Efficacious treatment for childhood SBPs have not included components more characteristic of treatment of adults, such as concepts of grooming, offense cycles, predation, or use of techniques such as confrontation or arousal reconditioning.105 For children who have histories of sexual abuse and trauma-related symptoms, a trauma-focused CBT approach that includes SBP-specific strategies has been successful.111–113

For some children, the SBP may be part of a general pattern of disruptive and oppositional behaviors. Research on treatment for disruptive behaviors has consistently identified behavior management training as an effective modality.114,115 Integrating SBP-specific treatment components with well-supported treatment models for early disruptive behavior disorders (such as Parent-Child Interaction Therapy,114 The Incredible Years,116 Barkley’s Defiant Child protocol,117 or the Triple P program118) might be considered; however, this approach has yet to be tested in regard to reducing SBPs.

The presence of attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder is not uncommon in these youth,106 and appropriate treatment is warranted to facilitate control of impulsive behaviors (see Chapter 16). In cases of neglectful, conflicted, or chaotic family environments, interventions focused on creating a safe, healthy, stable, and predictable environment may be the top priority.119 For cases in which insecure attachment is a major concern, short-term interventions emphasizing parental sensitivity have been found to be the most effective.120 Family-based attachment-based treatment may be considered for complex cases involving significant family relationship concerns, as well as comorbid conditions,86 although this approach has yet to be empirically validated.

Problematic Sexual Behavior during Adolescence

Adolescent sexual offenders are adolescents between the ages of 13 and 17 years who commit sexual behavior that is illegal as defined by the sex crime statutes of the jurisdiction in which the offense occurred.121 In general, the legal system (i.e., family or juvenile court, probation officer, judge, district attorney) is involved when an adolescent commits a sexual crime, because of the adolescent’s assumed culpability in committing the crime. The response of the legal system to an adolescent’s sexual crime varies greatly by state and may include court-ordered treatment, probation, imprisonment in a juvenile or adult correctional facility, and/or inclusion in registrations and public notification systems. Approximately one third of sexual offenses against children are committed by adolescents. Sexual offenses against children younger than 12 years tend to be committed by boys aged 12 to 15 years.122,123 The majority of adolescent sexual offenders are male, accounting for 93% of all juvenile arrests for sex offenses, excluding prostitution.124

ORIGINS OF SEXUAL BEHAVIOR PROBLEMS IN ADOLESCENTS

Adolescents with SBPs are a heterogeneous population.125,126 Although it is commonly believed that adolescent sexual offenders were sexually abused themselves, most in fact were not childhood sexual abuse victims.127,128 Some differences in maltreatment history between adolescent boys and girls with SBPs have been found. Adolescent girls with SBPs have been shown to have more severe physical and sexual abuse histories than have adolescent boys with SBPs. For adolescents with SBPs and who have been sexually abused, the girls tended to be sexually abused at younger ages and were more likely to have been abused by multiple perpetrators.127–131 There appears to be multiple origins, including abuse history, family stability, and psychiatric disturbances in the development of SBPs in adolescence; however, for many adolescents, there is no known cause.10

RISKS, COMORBIDITY, AND TYPOLOGY

Although professionals have proposed subtypes of adolescent sexual offenders, these subtypes have not yet been confirmed in the literature. What is known is that adolescent sexual offenders are diverse. There are adolescent sexual offenders with few other behavioral or psychological problems and those with many nonsexual behavior problems or other (nonsexual) delinquent offenses. Some have psychiatric disorders. Some adolescent sexual offenders come from well-functioning families; others come from poorly functioning or abusive families.10 Adolescents with SBPs tend to have poorer social skills, more behavior problems, learning disabilities, depression, and impulse control problems in comparison with nonoffending adolescents (see Becker125 for a review). Some differences have been found between adolescents who rape peers and those whose sexual behavior is with younger children. Adolescents whose sexual behavior is with younger children have been found to be younger, to be less socially competent, to have less same-age sexual activity, to be more withdrawn, and to have fewer nonsexual behavior problems than do adolescents who rape peers.132,133 Risk predictors that have been identified for sexual and nonsexual repeated offending, include antisocial tendencies, psychopathy, and larger numbers of victims.134

CONTRASTING ADOLESCENTS WITH SEXUAL BEHAVIOR PROBLEMS WITH ADULT SEXUAL OFFENDERS

Adolescents are different from adult sexual offenders in several important ways: (1) Adolescents are considered more responsive to treatment than are adults135; (2) of sexual offenders who receive treatment, adolescents have a lower sexual recidivism rate than do adults136; (3) adolescents have fewer victims and tend to engage in less aggressive behaviors than do adults137; and (4) most adolescents do not meet the criteria for pedophilia.138 With regard to recidivism, adolescent sexual offenders are less likely to have sexual repeated offenses and are more likely to have nonsexual repeated offenses than are adults.139

ASSESSMENT OF ADOLESCENTS

There are no psychological tests available that can establish guilt or innocence of committing a sexual offense. However, there are some measures under development to assess the risk of future sexual offenses of adolescent sexual offenses. The National Center on Sexual Behavior of Youth (www.ncsby.org) provides more guidelines about assessment of adolescent sexual offenders.

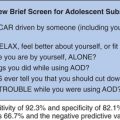

For adolescents with histories (e.g., maltreatment, life stressors, behavior problems) that make it more likely that they will engage in high-risk sexual behaviors or have sexual concerns, it is important for clinicians to assess their sexual practices and concerns to guide intervention. The Adolescent Clinical Sexual Behavior Inventory (ACSBI) can be used as a screening tool with such adolescent clinical samples. The ACSBI has parent- and self-report versions (45 items each), responses to which can provide information about adolescent’s high-risk sexual behavior and help determine appropriate interventions. The ACSBI measures a range of sexual behaviors and yields five factors: sexual knowledge/interest, divergent sexual interest, sexual risk/misuse, fear/discomfort, and concerns about appearance.140

TREATMENT FOR ADOLESCENT SEXUAL OFFENDERS (AGED 13 TO 17 YEARS)

Rigorous research regarding treatment of adolescent sexual offenders is lacking. However, there is some evidence to support the use of sex offender–specific treatment for adolescent sexual offenders. Two randomized clinical trials with small sample sizes yielded results in support of the use of multisystemic therapy with adolescent sexual offenders. Multisystemic therapy is a home-based treatment intervention that targets the systems in which youth are embedded, as well as the factors that are associated with delinquency. Results from these studies indicated that youths who received multisystemic therapy had lower rates of sexual and nonsexual recidivism than did youths who received the usual services (e.g., individual or group treatment).139,141,142 On the basis of what is known about juvenile sex offenders, state-of-the-art treatment recipients should include caregivers, so that relevant factors (e.g., parental monitoring and engagement) associated with delinquent behavior can be addressed.139 Because of the low rates of pedophilia among adolescent sexual offenders, it is generally inappropriate to apply adult sexual reconditioning techniques to adolescent sexual offenders. The widely held belief that most adolescent sexual offenders will become adult sex offenders is not supported by research.135

RECOMMENDATIONS CONCERNING CLINICAL CARE

Parent Education and Clinical Management: Children (Aged 3 to 12 Years)

Concerns about sexual behavior of youth may manifest in a variety of ways in the medical office. During assessment of a wide range of behavior problems, concerns about respect of other’s boundaries and sexual acts may arise. As sexual behavior, particularly in young children, often raises suspicion of sexual abuse, such children’s caregivers may express concern about possible victimization of the child. Families and other professionals may seek advice for follow-up and management once SBPs have been identified.

Parents are generally interested in and expect pediatricians to discuss normal sexuality and sexual abuse prevention.143 When there are concerns about SBPs, information provided depends on the results of the initial screening and, if warranted, further evaluation. In determining whether sexual behavior is inappropriate, it is important to consider whether the behavior is common or rare for the child’s developmental stage and culture, the frequency of the behaviors, the extent to which sex and sexual behavior have become a preoccupation for the child, and whether the child responds to normal correction from adults or whether the behavior continues after normal corrective efforts.119 In determining whether the behavior involves potential for harm, it is important to consider the age/developmental differences of the children involved; any use of force, intimidation, or coercion; the presence of any emotional distress in the children involved; whether the behavior appears to be interfering with the children’s social development; and whether the behavior causes physical injury.9,144,145

Parent education may include information about typical sexual development and how to distinguish SBPs from sex play; specific instructions for reducing exposure to sexually stimulating media or situations in the home; instructions for monitoring interactions with other children; suggestions for how parents should respond to sexualized behaviors; and teaching children rules about privacy, sexual behavior, and boundaries.119,146

Parents and caregivers often are understandably concerned about the causes of the SBP. In some cases, there appears to be relatively clear sequence of events that explain the development of the SBP (such as young child’s being sexually abused by an uncle, followed by the child’s repeating the behavior with another child at daycare). However, such direct pathways are often not present, inasmuch as causes for human behavior can involve the interplay of multiple factors, and may not be fully knowable.8 Parents can be reassured that children with SBPs can be treated successfully without clear evidence of the origins of the behavior, with the exception of situations of ongoing sexual abuse.

Ongoing sexual abuse is of serious concern, both for the child’s welfare and for the success of intervention efforts. Indeed, subsequent sexual abuse appears to increase the likelihood of future SBPs.105 In cases in which the Child Protective Services investigation of sexual abuse yields inconclusive results, interventions focused on educating children about sexual abuse, identifying whom children may tell if they were being abused, having significant adults support this message, and building support systems around the child have been recommended.73 Repeated questioning and interviewing the child after thorough investigations are not recommended, because they may lead to inaccurate information and have potential deleterious effects on the child.119

Other parental concerns often relate to the misunderstanding about the meaning of childhood SBPs and likelihood of problematic adult sexual behavior, including pedophilia. The results of a 10-year prospective study of children with SBPs indicated low rates of future sexual offenses (2% to 10%, depending on treatment type).105 A continuation of SBPs from childhood into adolescence and adulthood appears rare. Calm parental responses to these situations are advised.147 Efficacious treatments have been outpatient and short-term and have involved helping the children while living in their natural environment and while attending school. Restricted environments and treatments should be reserved for children who pose immediate risk because of coercive, aggressive, harmful sexual behavior that has not been readily modifiable with appropriate parental interventions and treatment.8

Resources are available to professionals in their work with parents. Fact sheets addressing typical sexual development, SBPs, and common misconceptions about child with SBPs can be found on the Website of the National Center on the Sexual Behavior of Youth (www.ncsby.org). An information booklet on child sexual development and SBPs145 is useful to supplement education for the caregivers (www.TCavJohn.com). Anticipatory guidelines on issues related to sexual development and behavior throughout childhood and adolescents with information on ways to approach issues of sexual development, sexuality, sexual behavior, and sexual abuse prevention designed for pediatric practice are available.2,147 In addition, the report from the Task Force on Children with Sexual Behavior Problems of the Association of the Treatment of Sexual Abusers is a useful resource for professionals (www.atsa.org).8 This report provides more a detailed review of the research and guidelines on the identification, clinical assessment, treatment, and policy issues relevant to children with SBPs.

Parent Education and Clinical Management: Adolescents (Aged 13 to 17 Years)

Caregivers and referring providers may need support in how to address sexual topics with youth. Furthermore, because of the sensitive and, at times, taboo nature of the topic, cultural considerations and sensitivity are necessary in approaching and educating about sexual matters. Guidelines for pediatricians and family practitioners on assessment and management sexual topics with adolescents and caregivers are available.2,6,147 Caregivers often require education in addition to the youth. Helpful resources for caregivers can be found at www.advocatesforyouth.org and www.talkingwithkids.org.

When an adolescent is suspected of engaging in illegal sexual behavior, providers need to respond in a manner consistent with the reporting requirements for their state, including reporting suspected illegal sexual behavior with children as indicated. Developmental-behavioral pediatricians can help caregivers and adolescents by referring youths for clinical assessment and efficacious treatment when available.

Unfortunately, efficacious treatment is not available in all areas of the United States. If efficacious treatment is not available, then the developmental-behavioral pediatrician should look for cognitive-behavioral treatment programs that involve both adolescents and caregivers and do not use adult sex offender treatment interventions (e.g., penile plethysmograph, polygraph) that may be inappropriate for adolescents.

Typically, adolescent sexual offenders can be treated in the community in outpatient treatment programs. Most adolescent sexual offenders can remain in the community with appropriate supervision by caregivers and probation officers and can be treated on an outpatient basis.135 In general, adolescent sexual offenders who are being treated in the community can attend school and engage in other activities, such as team sports and church. However, a small number of adolescent sexual offenders may need a higher level of care (i.e., residential or custodial placement).

Currently, there is no scientifically supported test to determine which adolescent sexual offenders are at high risk for recidivism. Usually, it is appropriate to treat an adolescent sexual offender as being at low risk for recidivism and in an outpatient setting, unless there is evidence that they are at higher risk. There are clinical guidelines to help identify youths at higher risk in order to help determine the level of care (outpatient vs. residential) that they may require. These factors are important in determining risk: (1) a history of multiple sexual offenses, particularly if sexual offenses continue despite appropriate treatment; (2) a history of multiple nonsexual juvenile offenses; (3) sexual attraction to children; (4) noncompliance with an adolescent sexual offender treatment program; (5) other “self-evident risk signs,” including significant behavior problems and stated intent to commit repeated sexual offenses; and (6) caregivers’ not providing the appropriate and recommended supervision and/or caregivers who are not compliant with treatment or probation.121

Collaboration with Family and Other Professionals and Agencies (Ages 3 to 17 Years)

As discussed in Chapter 8A, family-centered and collaborative approaches to service delivery are crucial for all children with developmental and behavioral needs. This is particularly true for children with SBPs and adolescent sexual offenders, for whom not only parents and caregivers but also other treatment providers, child welfare workers, schools, child care providers, juvenile justice staff, and court officials are involved in the care. The extent of collaboration and who may need to be included can be expected to vary considerably across cases. Main purposes of coordination and information sharing are to define service goals, articulate a clear plan and timetable of specific tasks needed to reach those goals, identify who on the team is responsible for each aspect of the plan, and evaluate plan implementation and goal attainment.8

OTHER RELEVANT TOPICS

Homosexuality

The sexual behavior of youth who identify themselves as gay, lesbian, or bisexual or who report homosexual or bisexual experiences are to be assessed with sensitivity and with nonjudgmental response and information. Education and intervention (e.g., information about relationships, decision making, self-care, reproduction, sexually transmitted diseases, protection) similar to that given to heterosexual youths often needs to be provided. In addition, the clinician should also be aware of the increased risk for other problems in homosexual or bisexual youths. These youths may feel extremely isolated from their peers and/or families and may have been the victims of violence and harassment.148 Nonheterosexual youth are at higher risk for behavioral and emotional problems and risky behaviors, including drug use and abuse, self-harm, school problems, and suicide.2,149 The American Academy of Pediatrics’ Committee on Adolescence’s clinical report on sexual orientation and adolescents provides useful information and guidelines for the care and support of youths.64

Children and Adolescents with Developmental Delays and Disabilities

In addition to the typical topics for sexual education, youths with disabilities may need focused information on ways to express physical affection, with whom, and under what circumstances, with an understanding of the youth’s need for intimacy and affection. Because of the increased risk of sexual abuse of such children, education should include sexual abuse prevention components. Self identity, developing relationships, and intimacy are important areas neglected in many sexual education programs for all youths. Caregivers and providers can be encouraged to provide guidance and education based on individual learning styles and disability-specific challenges, considering the use of visual supports (e.g., pictures, dolls), repeating information over time, and having the youth demonstrate or practice the information learned.2,67 Issues of consent, marriage, and family planning are complicated and require collaborative care and an understanding of individuals’ desires, choices, capabilities, supports, and needs. Curriculum on sex education for children and youths with disabilities are available150 (see also the University of South Carolina Center for Disability Resource Library at http://uscm.med.sc.edu/CDR/sexualeducation.htm), as well as other useful information including one from the American Academy of Pediatrics.67,151

Cultural Factors Affecting Parental Education and Other Service Provision

Consideration of the child and family’s cultural values, beliefs, and norms are of foremost importance in the provision of any mental health and social services. Race, ethnicity, religion, spirituality, socioeconomic factors, and other cultural factors can strongly affect individuals’ and families’ receptivity and response to treatment of child SBPs. Professionals are advised to account for the effect of the specific social ecology experience of the child. Significant variation among children exists, inasmuch as cultural and social context, as well as family attitudes and educational practices, affect children’s knowledge and behavior.18,19,30

Because of the sensitive nature of the topic, clinicians must become knowledgeable about the family’s and community’s beliefs, values, traditions, and practices concerning sex, including the spoken and unspoken rules about public and private behavior, relationships, intimacy, and modesty. For example, discussions on sexual behavior with children may be considered appropriate for some individuals (e.g., aunts teaching nieces) but taboo for others (e.g., fathers talking with daughters). Provision of education in a manner consistent with the culture and family beliefs are recommended. African-American mothers have been found to integrate story telling in process of providing sex education.152 Storytelling is also integral for American Indron Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian families.153 Beliefs about the appropriateness of children’s touching their own private parts and about masturbation tend to be strong and directly affect receptiveness to treatment. Understanding and respecting the cultural beliefs and values of families and providing services to enhance the family’s ability to accept and receive the services is crucial not only for outcome but also for initiation and retention of families in services.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Although research on children and adolescent sexual knowledge began decades ago, research on children and adolescents with SBPs is a relatively new area of research. There remain many questions about knowledge and behavior of children and adolescents, particularly in the origins, typology, course, assessment, treatment, and long-term outcome for children and adolescents with SBPs. The following sections address some of the methodological challenges to research on the sexual knowledge and behavior of children and youth, as well as recommendations for future research.

Methodological Issues

Conducting research on the sexual knowledge and sexual behavior of children and youth has multiple challenges. Parents who allow their young children to participate in research on sexual knowledge may have distinct values and parenting practices from those who do not allow their children to participate. In one study, researchers noted that the majority of parents approached chose not to have their child participate; the concern about topic reported was the reason for declining.18 The unknown effect of participation bias limits the generalizability of results.

Much of the research on children’s sexual behavior has relied on caregivers’ or teachers’ reports. Self-reports of sexual behavior from adolescents suggest higher prevalence of sexual behaviors and sexual assaults than has been detected by administrative systems (such as child protective services, juvenile court system). Furthermore, retrospective research with adults suggests that caregivers are often unaware of sexual behavior that occurs among children. Retrospective research, although useful, relies on the memory of the adults, which is affected by a variety of factors. Administrative data sources track only the more severely maladaptive sexual behaviors and are also subjected to a variety of biases. The hidden nature of the sexual behavior of youths, particularly school-aged children and adolescents, challenges direct observations. Direct questioning of children and even adolescents about their sexual behavior is often restricted, particularly in the United States. Thus, reliable and valid information about children and adolescents sexual behavior is difficult to obtain, which further affects researchers’ ability to track and examine factors that affect the trajectory of sexual behaviors.

Examination of treatment efficacy for SBPs of children and adolescent poses additional challenges. Because of the concerns about the ramifications of ongoing SBPs, randomized trials with no treatment or placebo control conditions are generally considered unethical. Quasi-experimental designs and preintervention/postintervention evaluations limit clinicians’ ability to progress in understanding intervention efficacy. Randomly assigning children to receive one of two treatments when both interventions are believed to be efficacious requires a considerable sample size, perhaps multisite studies, to determine differences in effect sizes.

Recommendations for Future Research

Even basic information about SBPs in children and adolescents, such as prevalence and incidence data, is unavailable. National data on the incidence, prevalence, and frequency of types of sexual behaviors in children and youth would greatly enhance the literature. Clear, consistent definitions of types of sexual behaviors are necessary. Furthermore, because no single state or federal agency is designated as responsible for assessing and responding to sexual behavior of youths, the collection of incidence and prevalence data is challenged.

There is considerable research to be done in the area of clinical assessment of children and adolescents with SBPs. The CSBI88 is the only norm-based measure of sexual behaviors of youth and is quite useful for clinical assessment, as well as monitoring treatment progress. The published version of the measure does not include items to assess aggressive or coercive sexual behaviors; however, Friedrich evaluated four such items after the published measure.33 The published norms are based predominately on data from Caucasian and African-American children. Cross-cultural research with normative data from other populations is needed. No norms are available for the accompanying Safety Checklist.33 The Child Sexual Behavior Checklist98 includes items that assess broad issues such as environmental factors, in addition to specifics about the types and other details about SBPs. Although the measure is clinically useful, no norms have yet been published. Research is also needed in how to sensitively and culturally appropriately measure children’s sexual thoughts and understanding of their sexual behaviors.

There is one measure of adolescent sexual behavior: the ACSBI.140 This is a useful measure for clinically referred adolescents and can help guide treatment. However, there is no normative sample for this measure. The clinical sample used for development was primarily white and of middle to upper middle socioeconomic status. Research on normative sexual behavior of adolescents, including cross-cultural and economically diverse samples, is needed. One important assessment question is estimating the likelihood of sexual and nonsexual repeated offense. Although there are some adolescent sexual offender actuarial systems under development, this is still an area for continued research.

An untapped area of measurement concerns the caregivers’ knowledge of, reaction to, and perception of their child and the sexual acts. Mothers’ emotional reaction and support has been found to mediate treatment outcomes for preschool- and school-aged sexually abused children.107,154,155 Clinically, caregivers’ perceptions of their children who have demonstrated SBPs appear to strongly affect their willingness to support the child, engage in services, and respond to intervention. Psychometrically supported measures of caregiver’s emotional reaction to, support of, and perceptions for this specific population would facilitate research in this area.

Origins, trajectory, risk factors, and treatment outcome probably vary for subgroups of children and adolescents with SBPs. Typologies have been proposed on the basis of the types of sexual behavior exhibited, as well as other factors (such as gender, comorbid conditions and nonsexual delinquent acts). No clear classification has yet emerged to advance understanding in this area.

Additional research on such service factors as group versus individual/family services, use of direct practice of skills with families in session, and need of specific components of treatment (such as acknowledging past SBPs) would advance the field. Because of the low base rates of subsequent sexual offenses in children,105 it is unlikely that refined services would significantly lower this rate any further. However, researchers could examine improvements of less severe sexual behaviors, receptivity of services by families, reduced treatment burden, treatment attrition, comorbid symptom relief, and gains in coping skills and resiliency factors.

Research on services in more restrictive settings (i.e., inpatient and residential interventions) for children and adolescents with persistent, aggressive SBPs is limited to clinical descriptions and quasi-experimental designs. These youths are also more likely to have histories of severe trauma, comorbid conditions, and problematic family histories and situations (e.g., mental illness, substance abuse, maltreatment, community and domestic violence).

Many youths with SBPs have comorbid conditions of post-traumatic stress disorder, separation anxiety, and/or disruptive behavior disorders (including oppositional defiant disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and conduct disorder). Although evidence-based treatments exist for each of these conditions, research on the most efficacious and efficient manner to integrate these services for children with comorbid conditions, in such a way that it is also palatable for families, is needed.

In many ways, the treatment outcome research on children with SBPs is more advanced than the research literature on adolescent and adult sex offender treatment outcomes. Only investigations of multisystemic therapy have amassed any controlled trial data with adolescents. Thus, many treatment questions remain. Comparisons of community-based treatments with residential treatment are particularly important, in view of the possible iatrogenic effects of residential placement.

The results of the prospective studies on children and adolescents with SBPs are encouraging but limited to a few studies focusing on administrative data sources. Longitudinal research integrating administrative data with self- and caregiver-disclosed rates of SBPs, other delinquent acts, victimization, and trauma experiences is warranted. Preschool-aged children with SBPs have been found to have much more frequent SBPs, more severe comorbid conditions, and greater rates of placement disruptions than do school-aged children with SBPs.78 Trajectories of nonsexual disruptive behaviors (particularly physical aggression) have been found to be distinct, depending in part on age at onset, wherein a younger onset is related to more severe and pervasive problems (e.g., Broidy et al156). Longitudinal research with preschool- as well as school-age onset of SBPs would facilitate the examination of whether SBPs have a pattern similar to that of other disruptive behaviors.

In summary, initial results in this relatively new area of research are encouraging, but further research is warranted for prevalence and incidence data, assessment, typology, treatment mediators and outcome, and longitudinal trajectories.

SUMMARY

Children are sexual beings from birth, capable of sexual arousal and behavior even as infants. Sexual knowledge and behavior are affected not only by physiology but also by family, culture, and societal factors. Curiosity and exploratory play are typical in early childhood. Sexual activity and risky sexual behaviors increase throughout childhood, particularly with the onset of puberty. Sensitivity in provision of care is recommended, particularly for populations who have experienced disparities in health care, including nonheterosexual youths, individuals with disabilities, and individuals from nondominant cultures.