CHAPTER 22 Sleep and Sleep Disorders in Children

NORMAL SLEEP IN INFANTS, CHILDREN, AND ADOLESCENTS

Although sleep in neonates and infants is quite different from that in adults, the structure of children’s sleep and sleep-wake patterns begin to resemble those of adults as they mature.1 In terms of sleep architecture, there is a dramatic decrease in the proportions of both rapid eye movement (REM) sleep and slow-wave sleep (delta or deep sleep) from birth through childhood to adulthood. Sleep cycles during the nocturnal sleep period (known as the ultradian rhythm of sleep) lengthen, which results in fewer spontaneous arousals. Several general trends in the maturation of sleep patterns over time have also been identified. First, there is a decrease in the 24-hour average total sleep duration from infancy through adolescence, with a less marked and more gradual continued decrease in nocturnal sleep amounts into late adolescence.2 This decline includes a decrease in nocturnal sleep throughout childhood, as well as a significant decline in daytime sleep (scheduled napping) between 18 months and 5 years. There is also a gradual but marked circadian-mediated shift to a later bedtime and sleep onset time that begins in middle childhood and accelerates in early to middle adolescence. Finally, sleep-wake patterns on school nights and nonschool nights become increasingly irregular from middle childhood through adolescence. However, sleep patterns also reflect the complex combined influence of biological, environmental, and cultural factors and thus may differ substantially across different cultures and in different contexts.3 The following section provides a more detailed description of normal sleep behaviors and patterns in different age groups.

Sleep in Newborns

Newborns sleep approximately 16 to 20 hours per day, generally in 1- to 4-hour periods asleep followed by 1- to 2-hour periods awake, and sleep amounts during the day are approximately equal to the amount of nighttime sleep. Sleep-wake cycles are largely dependent on hunger and satiety; for example, bottle-fed babies generally sleep for longer periods (3 to 5 hours) than do breastfed babies (2 to 3 hours). Newborns have two sleep state that are essentially analogous to adult REM and non-REM sleep: active (“REM-like,” characterized by smiling, grimacing, sucking, and body movements; 50% of sleep) and quiet (“non-REM-like”), as well as a third “indeterminate” state. Unlike adults and older children, newborns and infants up to the age of approximately 6 months enter sleep through the active or REM-like state.4

Sleep in Infants (Aged 1 to 12 months)

Infants generally sleep about 14 to 15 hours per 24 hours at age 4 months and 13 to 14 hours total at age 6 months; however, there appears to be a very wide intraindividual variation in parent-reported 24-hour sleep duration in the first year of life.2 Sleep periods last about 3 to 4 hours during the first 3 months and extend to 6 to 8 hours by the age of 4 to 6 months. Most infants between 6 and 12 months of age nap a total of 2 and 4 hours, divided into two naps, per day.5

Two important developmental “milestones” are normally achieved during the first 6 months of life; these are known as sleep consolidation and sleep regulation.6 Sleep consolidation is generally described as an infant’s ability to sleep for a continuous period of time that is concentrated during the nocturnal hours, augmented by shorter periods of daytime sleep (naps). Infants develop the ability to consolidate sleep between ages 6 weeks and 3 months, and approximately 70% to 80% of infants achieve sleep consolidation (i.e., “sleeping through the night”) by age 9 months. Sleep regulation is the infant’s ability to control internal states of arousal in order both to fall asleep at bedtime without parental intervention or assistance and to fall back asleep after normal brief arousals during the night. The capacity to self-soothe begins to develop in the first 12 weeks of life and is a reflection of both neurodevelopmental maturation and learning. However, the developmental goal of independent self-soothing in infants at bedtime and after night awakenings may not be shared by all families, and voluntary or lifestyle sharing of bed or room by infants and parents is a common and accepted practice in many cultures and ethnic groups. Sleep behavior in infancy, in particular, must also be understood in the context of the relationship and interaction between child and caregiver, which greatly affects the quality and quantity of sleep.7,8

Sleep in Toddlers (Aged 12 to 36 months)

Toddlers sleep about 12 hours per 24 hours. Napping patterns generally consist of ½ to 3½ hours per day, and most toddlers give up a second nap by age 18 months. During this stage, both developmental and environmental issues begin to have more of an effect on sleep; examples include the development of imagination, which may result in increased nighttime fears; an increase in separation anxiety, which may lead to bedtime resistance and problematic night awakenings; an increased understanding of the symbolic meaning of objects, which can lead to increased interest in and reliance on transitional objects to allay normal developmental and separation fears; and an increased drive for autonomy and independence, which may result in increased bedtime resistance. Sleep problems in toddlers are very common, occurring in 25% to 30% of this age group; bedtime resistance occurs in 10% to 15% of toddlers, and night awakenings occur in 15% to 20%.9,10

Sleep in Preschoolers (Aged 3 to 5 years)

Preschool-aged children typically sleep about 11 to 12 hours per 24 hours; most children give up napping by 5 years, although approximately 25% of children continue to nap at age 5, and there is some evidence that napping patterns and the preservation of daytime sleep periods into later childhood may be influenced by cultural differences.11 Difficulties falling asleep and night awakenings (15% to 30%) are still common in this age group, in many cases coexisting in the same child.12 Developmental issues affecting sleep include expanded language and cognitive skills, which may lead to increased bedtime resistance, as children become more articulate about their needs and may engage in more limit-testing behavior; a developing capacity to delay gratification and anticipate consequences, which enables preschoolers to respond to positive reinforcement for appropriate bedtime behavior; and increasing interest in developing literacy skills, which reinforces the importance of reading aloud at bedtime as an integral part of the bedtime routine. Bedtime routines and rituals, use of transitional objects, and sleep-wake schedules are all important sleep-related issues at this developmental stage.

Sleep in Middle Childhood (Aged 6 to 12 years)

Most children this age sleep between 10 and 11 hours a night. It is important to note that the presence of daytime sleepiness in an elementary school-aged child is likely to be indicative of significant sleep problems that cause insufficient or poor quality sleep, because of the high level of physiological alertness during the day that is characteristic of school-aged children. Middle childhood is also a critical time for the development of healthy sleep habits. Increasing independence from parental supervision and a shift in responsibility for health habits as children approach adolescence may result in less enforcement of appropriate bedtimes and inadequate sleep duration; parents may also be less aware of sleep problems if they do exist. Although sleep problems were previously believed to be rare in middle childhood, studies have revealed an overall prevalence of significant parent-reported sleep problems of 25% to 40%, ranging from bedtime resistance to significant sleep onset delay and anxiety at bedtime.13,14

Sleep in Adolescents (Aged 12 to 18 years)

Although a number of significant sleep changes occur in adolescence, adolescents’ sleep needs do not differ dramatically from those of preadolescents, and optimal sleep amounts remain at about 9 to 9¼ hours per night. However, a number of studies across different environments and in different cultures have suggested that the average adolescent typically sleeps about 7 hours or less per night15 and that this accumulating sleep debt may have a significant effect on functioning, performance, and quality of life. Biologically based pubertal changes also significantly affect sleep. In particular, around the time of onset of puberty, adolescents develop as much as a 2-hour sleep-wake “phase delay” (later sleep onset and waking times) in relation to sleep-wake cycles in middle childhood.16 Environmental factors and lifestyle/social demands, such as homework, activities, and after-school jobs, also significantly affect sleep amounts in adolescents, and early start times of many high schools may contribute to insufficient sleep. There is significant weekday/weekend variability in sleep-wake patterns in adolescents, often accompanied by weekend oversleep in an attempt to address the chronic sleep debt accumulated during the week; this further contributes to decreased daytime alertness levels. All of these factors often combine to produce significant sleepiness in many adolescents and consequent impairment in mood, attention, memory, behavioral control, and academic performance.17,18

NEUROBEHAVIORAL AND NEUROCOGNITIVE EFFECT OF INADEQUATE AND DISRUPTED SLEEP IN CHILDREN

There is clear evidence from both experimental laboratory-based studies and clinical observations that insufficient and poor quality sleep result in daytime sleepiness and behavioral dysregulation and affect neurocognitive functions in children, especially the functions involving learning and memory consolidation and those associated with the prefrontal cortex (e.g., attention, working memory, and other executive functions).19 Indeed, positron emission tomographic scans of sleep-deprived adults show decreased glucose metabolism in the prefrontal cortex, similar to the changes in neural function seen in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Sleep loss and sleep fragmentation are known to directly affect mood (increased irritability, decreased positive mood, poor affect modulation). Behavioral manifestations of sleepiness in children are varied and range from those that are classically “sleepy,” such as yawning, rubbing eyes, and/or resting the head on a desk, to externalizing behaviors, such as increased impulsivity, hyperactivity, and aggressiveness, to mood lability and inattentiveness.20 Sleepiness may also result in observable neurocognitive performance deficits, including decreased cognitive flexibility and verbal creativity, poor abstract reasoning, impaired motor skills, decreased attention and vigilance, and impaired memory.21,22

Clinical experience, as well as empirical evidence from numerous studies and case reports, have demonstrated that childhood sleep disorders both arising from intrinsic processes, such as obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS), and those related to extrinsic or environmental factors, such as behavioral insomnia of childhood (sleep onset association type and limit-setting type) and insufficient sleep, may manifest primarily with daytime sleepiness and neurobehavioral symptoms. The pediatric sleep disorders that have been most frequently studied from this perspective include sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) (i.e., OSAS and snoring), and restless legs syndrome (RLS)/periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD). For example, a higher prevalence of parent-reported externalizing behavior problems, including impulsivity, decreased attention span, hyperactivity, aggression, and conduct problems has been frequently reported in studies of children with either polysomnographically diagnosed OSAS or symptoms suggestive of sleep-disordered breathing, such as frequent snoring.23,24 Investigators who have compared neuropsychological functions in children with OSAS have found impairments on tasks involving reaction time and vigilance, attention, executive functions, motor skills, and memory. Although some studies have documented significant short-term improvement in daytime sleepiness, behavior, and academic performance25 after treatment (usually adenotonsillectomy) for OSAS/SDB, other studies have suggested that young children with SDB may continue to be at high risk for poor academic performance several years after the symptoms have resolved.26 Alternatively, the prevalence of SDB symptoms in children with identified behavioral and academic problems has also been examined in several studies; overall, these studies have revealed an increased prevalence of snoring in young children with behavioral and school concerns, which is suggestive of an approximately twofold increased risk of habitual snoring and SDB symptoms in children with high scores on behavior problem scales.27

Significant neurobehavioral consequences may also occur in relation to RLS/PLMD and, as described in several studies, may manifest with a symptom constellation similar to that of ADHD.28,29 A number of studies have revealed an increased prevalence of periodic limb movements on polysomnography in children referred for ADHD; furthermore, treatment of these children with dopamine antagonists has been shown to result not only in improved sleep quality and quantity but also in improvement in “attention deficit/hyperactivity” behaviors previously resistant to treatment with psychostimulants.30

Other postulated health outcomes of inadequate sleep in children include potential deleterious effects on the cardiovascular, immune, and various metabolic systems, including glucose metabolism and endocrine function, and an increase in accidental injuries.31 In addition, studies have documented secondary effects on parents (e.g., maternal depression), as well as on family functioning.32

COMMON SLEEP DISORDERS IN CHILDREN: ETIOLOGY, EPIDEMIOLOGY, PRESENTATION, EVALUATION, AND TREATMENT

Sleep-Disordered Breathing and Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome

SDB in childhood includes a spectrum of disorders that vary in severity, ranging from OSAS to primary snoring (snoring without ventilatory abnormalities).33–35 The prevalence is also variable, from 1% to 3% of children with OSAS to 10% of children with habitual snoring. The basic pathophysiological process of OSAS involves cessation of airflow through the nose and mouth during sleep (pathological duration of an apnea is determined by age-appropriate norms) despite respiratory effort and chest wall movement; this disrupts normal ventilation during sleep, resulting in hypoxemia and/or hypoventilation and a sleep pattern characterized by frequent arousals.36 Common manifestations of SDB in childhood include loud, nightly snoring; choking/gasping arousals; and increased work of breathing characterized by nocturnal diaphoresis, paradoxical chest and abdominal wall movements, and restless sleep. However, as noted previously, SDB may manifest primarily with neurobehavioral symptoms, including inattention and poor academic functioning. Although repeated episodes of nocturnal hypoxia probably constitute an important etiological factor for neurobehavioral deficits in OSAS, sleep fragmentation resulting from frequent nocturnal arousals, which in turn leads to the daytime sleepiness, is also believed to play a key role.

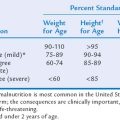

Specific physical examination findings (growth abnormalities such as obesity or failure to thrive, nasal obstruction with hyponasal speech and “adenoidal facies” or mouth breathing, enlarged tonsils) may raise suspicion of OSAS. However, the presence of large tonsils and adenoids does not necessarily mean the patient has OSAS, and there is in fact no constellation of presenting symptoms and physical findings that have reliably been found to differentiate between OSAS and primary snoring in the ambulatory setting.37 Overnight polysomnography remains the “gold standard” for evaluating pediatric SDB; it documents physiological variables during sleep, including sleep stages and arousals (electroencephalographic montage, eye movements, chin muscle tone), cardiorespiratory parameters (air flow, respiratory effort, oxygen saturation, transcutaneous or end-tidal CO2, and heart rate), and limb movements and allows for both confirmation of the diagnosis and assessment of severity of OSAS.

Adenotonsillectomy is generally the first line of treatment for pediatric SDB, although adenoidectomy alone may not be curative when other risk factors such as obesity are present.38 Adenoids may also “grow back” as the result of continued hypertrophy of residual adenoidal tissue after surgery. Reported cure rates after adenotonsillectomy range from 75% to 100% in normal healthy children. Nutrition and exercise counseling should be a routine part of treatment for SDB in obese children. Continuous Positive airway pressure, the most common treatment for OSAS in adults, can be an effective and reasonably well-tolerated treatment option for those children and adolescents for whom surgery is not an option or in children who continue to have OSAS despite surgery.39,40 Little is known about the efficacy of other treatment modalities, such as oral appliances, palatal/pharyngeal surgery, or other noninvasive techniques such as external nasal dilators for OSAS in the pediatric population.

Parasomnias

Parasomnias are defined as episodic, often undesirable nocturnal behaviors that typically involve autonomic and skeletal muscle disturbances, as well as cognitive disorientation and mental confusion.41 Parasomnias may be further categorized as occurring primarily during stage 4 slow-wave or deep (delta) sleep (partial arousal parasomnias), during REM sleep, or at the sleep-wake transition.

PARTIAL AROUSAL PARASOMNIAS

The partial arousal parasomnias, which include sleepwalking and sleep terrors, typically occur in the first third of the night at the transition out of slow-wave sleep and thus share clinical features of both the awake state (ambulation, vocalizations) and the sleeping state (high arousal threshold, unresponsiveness to the environment, amnesia for the event).42 Sleep terrors are typically characterized by a very high level of autonomic arousal, whereas sleepwalking, by definition, usually involves displacement from bed. Both are more common in preschool- and school-aged children and generally disappear in adolescence, at least in part because of the relatively higher amount of slow-wave sleep in younger children. Sleep terrors are considerably less common (1% to 3% incidence) than sleepwalking (40% of the population have had at least one episode). Furthermore, any factors that are associated with an increase in the relative percentage of slow-wave sleep (certain medications, previous sleep deprivation, sleep fragmentation caused by an underlying sleep disorder such as OSAS) may increase the frequency of these events in a predisposed child.43 Finally, there appears to be a genetic predisposition for both sleepwalking and night terrors, and it is not uncommon for individuals to have both types of episodes.

Atypical manifestations of partial arousal parasomnias are sometimes difficult to distinguish from nocturnal seizures; the index of suspicion for a seizure disorder should be higher in the presence of a history of seizures or risk factors for seizures, any unusual or stereotypic movements accompanying the episodes, or postictal phenomena.44 Subsequent daytime sleepiness is also much more likely with nocturnal seizures. Home videotaping of the episodes may be helpful in making the diagnosis, but overnight polysomnography (with a full electroencephalographic seizure montage) may be necessary. The treatment of partial arousal parasomnias generally involves parental education and reassurance, avoidance of exacerbating factors such as sleep deprivation, and institution of safety precautions, particularly in the case of sleepwalking. Pharmacotherapy (with a slow-wave sleep-suppressing drug such as a benzodiazepine or tricyclic antidepressant) may be indicated in severe or chronic cases.

RHYTHMIC MOVEMENT DISORDERS

Rhythmic movement disorders, including body rocking, head rolling, and head banging, are parasomnias that occur largely during sleep-wake transition and are characterized by repetitive, stereotypic movements involving large muscle groups. They are much more common in the first year of life and generally disappear by age 4 years, but in rare cases they persist into adulthood.45 Although occasionally associated with developmental delay, most occur in normal children and do not result in physical injury to the child. Treatment is generally parental reassurance and, if appropriate, judicious padding of the sleeping surface.

BRUXISM

Bruxism, or repetitive nocturnal tooth grinding, occurs in as many as 50% of normal infants during eruption of primary dentition, and the incidence of at least occasional episodes approaches 20% in older children.45 There is some speculation that the underlying pathophysiology may be linked to alterations in serotonergic and dopaminergic neurotransmission in the central nervous system. Treatment of symptomatic bruxism (e.g., temporomandibular joint pain, wearing of teeth surfaces) generally involves the use of occlusal splints, and behavioral treatment (e.g., biofeedback) may also be useful.

Restless Legs Syndrome and Periodic Limb Movement Disorder

RLS and PLMD are related sleep disorders that are frequently overlooked in both adult and pediatric clinical practice.29 Although the prevalence of these disorders in the pediatric population is unknown, retrospective reports given by affected adults suggest that symptoms (such as restless sleep and discomfort in the lower extremities at rest) frequently first appear in childhood and can result in significant sleep disturbance. As in adults, RLS symptoms in children and adolescents are typically worse in the evening and are exacerbated by inactivity, leading to significant difficulty in falling asleep. Individuals with RLS describe uncomfortable, “creepy-crawly” sensations in the lower extremities rather than pain per se; however, these symptoms are often poorly articulated by the children themselves and may be expressed as “growing pains.” Additional diagnostic clues may include iron deficiency anemia (specifically, a low ferritin level), exacerbation of symptoms by caffeine intake, and a positive family history of RLS/PLMD. Periodic limb movements, which often co-occur with RLS (as many as 80% of adults with RLS also have periodic limb movements), are characterized by brief, repetitive, rhythmic jerks primarily of the lower extremities during stages 1 and 2 of sleep; these may result in sleep fragmentation related to nocturnal arousals and awakenings. The underlying pathophysiology of both disorders probably involves alterations in dopaminergic neurotransmission, but whereas RLS is a clinical diagnosis, documentation of periodic limb movements associated with arousals requires an overnight sleep study. Pharmacological management with a variety of agents such as dopamine agonists, opioids, and anticonvulsants, as well as iron supplementation if appropriate, and avoidance of exacerbating factors are often quite helpful.46

Narcolepsy

Narcolepsy is a rare primary disorder of excessive daytime sleepiness that affects an estimated 125,00 to 200,000 Americans.47,48 Narcolepsy is rarely diagnosed in prepubertal children, but retrospective surveys nonetheless suggest that in many cases it first manifests in late childhood and early adolescence. However, both pediatric and adult patients with narcolepsy often delay seeking medical attention and are frequently labeled as having mood disorders, learning problems, and academic failure before the underlying cause is identified, as long as several decades later.49 In about 25% of cases, there is a family history of narcolepsy; secondary narcolepsy after brain injury or in association with other medical illnesses may also occur.

Delayed Sleep Phase Syndrome

Delayed sleep phase syndrome is a circadian rhythm disorder that involves a significant and persistent phase shift in sleep-wake schedule (later bed and wake time) that conflicts with the individual’s school, work, and/or lifestyle demands.50 Thus, it is the timing rather than the quality of sleep per se that is problematic; sleep quantity may be compromised if the individual is obligated to wake up in the morning before adequate sleep is obtained. Individuals with delayed sleep phase syndrome may complain primarily of sleep initiation insomnia; however, when allowed to sleep according to their preferred later bedtime and waking time (e.g., on school vacations), the sleep onset delays resolve. The typical sleep-wake pattern in delayed sleep phase syndrome is a consistently preferred bedtime/sleep onset time after midnight and a waking time after 10 a.m. on both weekdays and weekends. Adolescents with delayed sleep phase syndrome often complain of sleep-onset insomnia, extreme difficulty waking in the morning, and profound daytime sleepiness. Delayed sleep phase may be treated with a combination of the imposition of a strict sleep-wake schedule, exogenous melatonin, and bright light therapy to help reset the patient’s inner clock.51 Teenagers with a severely delayed sleep phase (more than 3 to 4 hours) may benefit from chronotherapy, in which bedtime (“lights out”) and waking times are successively delayed (by 2 to 3 hours per day) over a period of days, until the sleep onset time coincides with the desired bedtime. If school avoidance or a mood disorder is part of the clinical picture, which is commonly the case, noncompliance with treatment is typical, and more intensive behavioral and pharmacological management strategies may be warranted.

Insomnia

BEHAVIORAL INSOMNIA OF CHILDHOOD

It is estimated that overall 20% to 30% of young children in cross-sectional studies are reported to have significant bedtime problems and/or night awakenings.1 For didactic purposes, the subtypes of behavioral insomnia of childhood, sleep onset association and limit-setting subtypes, are defined as separate entities.52 However, in reality, the two often coexist, and many children present with both bedtime delays and night awakenings.

The Limit-Setting Sleep Subtype

A review of 52 treatment studies indicated that behavioral therapies produce reliable and durable changes for both bedtime resistance and night awakenings in young children.53 Ninety-four percent of the studies reported that behavioral interventions were efficacious; more than 80% of children treated demonstrated clinically significant improvement, maintained for up to 3 to 6 months. In particular, results of controlled group studies strongly supported unmodified extinction, graduated extinction, and preventive parent education about sleep as efficacious behavioral treatment strategies. Extinction (or systematic ignoring) typically involves a program of withdrawal of parental assistance at sleep onset and during the night. Graduated extinction is a more gradual process of weaning the child from dependence on parental presence; in a common form, parents use periodic brief checks at successively longer time intervals during the sleep-wake transition. If the infant has become habituated to awaken for nighttime feedings (“learned hunger”), then these feedings should be slowly eliminated. In older children, the introduction of more appropriate sleep associations that are readily available to the child during the night (transitional objects such as a blanket or toy) in addition to positive reinforcement (e.g., stickers for remaining in bed) are often beneficial. Successful treatment of limit-setting sleep problems generally involves a combination of decreased parental attention for bedtime-delaying behavior, establishment of a consistent bedtime routine that does not include stimulating activities such as television viewing, “bedtime fading” (temporarily setting bedtime to the current sleep onset time and then gradually making bedtime earlier) and positive reinforcement (e.g., sticker charts) for appropriate behavior at bedtime. Older children may benefit from being taught self-relaxation techniques and cognitive-behavioral strategies to help themselves fall asleep more readily. For all of these behavioral strategies, parental consistency in applying behavioral programs is crucial to avoid inadvertent intermittent reinforcement of night awakenings; they should also be forewarned that protest behavior frequently temporarily escalates at the beginning of treatment (“postextinction burst”).

Psychophysiological Insomnia

Psychophysiological insomnia (difficulty with sleep onset and/or sleep maintenance) occurs primarily in older children and adolescents. This type of insomnia is frequently the result of the presence of predisposing factors (such as genetic vulnerability, underlying medical or psychiatric conditions) combined with precipitating factors (such as acute stress) and perpetuating factors (e.g., poor sleep habits, caffeine use, maladaptive cognitions about sleep). In this disorder, the individual develops conditioned anxiety around difficulty falling or staying asleep, which leads to heightened physiological and emotional arousal and further compromises the ability to sleep.54 Treatment usually involves educating the adolescent about principles of sleep hygiene, instructing him or her to use the bed for sleep only and to get out of bed if he or she is unable to fall asleep (stimulus control), restricting time in bed to the actual time asleep (sleep restriction), and teaching relaxation techniques to reduce anxiety.

SLEEP ISSUES IN SPECIAL POPULATIONS

Children with Neurodevelopmental Disorders

The high prevalence rates for sleep problems found in these populations of children, ranging from 13% to 85%, may be related to any number of factors, including intrinsic abnormalities in sleep regulation and circadian rhythms, sensory deficits, and medications used to treat associated symptoms.55,56 It is estimated that significant sleep problems occur in 30% to 80% of children with severe mental retardation and in at least half of children with less severe cognitive impairment. Estimates of sleep problems in children with autism and/or pervasive developmental delay are similarly in the range of 50% to 70%. The types of sleep disorders that occur in these children are generally not unique to these populations; rather, they are more frequent and more severe than in the general population, and they typically reflect the child’s developmental level rather than chronological age. Significant problems with initiation and maintenance of sleep, shortened sleep duration, irregular sleeping patterns, and early morning waking, for example, have been reported in a variety of different neurodevelopmental disorders, including Asperger syndrome, Angelman syndrome, Rett syndrome, Smith-Magenis syndrome, and Williams syndrome.55

Basic principles of sleep hygiene in children are particularly important to consider in preventing and treating sleep problems in children with developmental delays.57 Ensuring the safety of these children, especially if night waking is a problem or there is a history of self-injurious behavior, also must be a key consideration in management. A range of behavioral management strategies used in normal children for night awakenings and bedtime resistance, such as graduated extinction procedures and positive reinforcement, may also be applied effectively in children with developmental delay. Collaboration with a behavioral therapist may be needed if there are complex, chronic, or multiple sleep problems or if initial behavioral strategies have failed. Finally, the use of pharmacological intervention in conjunction with behavioral techniques, including melatonin, has also been shown to be effective in selected cases.58

Children with Psychiatric Disorders

Sleep disturbances often have a significant effect on the clinical manifestations and symptom severity, as well as on the management, of psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents. Virtually all psychiatric disorders in children may be associated with sleep disruption.59–61 Psychiatric disorders can also be associated with daytime sleepiness, fatigue, abnormal circadian sleep patterns, disturbing dreams and nightmares, and movement disorders during sleep. Studies of children with major depressive disorder, for example, have revealed a prevalence of insomnia of up to 75%, a prevalence of severe insomnia of 30%, and a prevalence of sleep onset delay in one third of depressed adolescents. Sleep complaints, especially bedtime resistance, refusal to sleep alone, increased nighttime fears, and nightmares, are also common in anxious children and in children who have experienced severely traumatic events (including physical and sexual abuse). Use of psychotropic medications that may have significant negative effects on sleep often complicates the issue. Conversely, growing evidence suggests that “primary” insomnia (i.e., insomnia with no concurrent psychiatric disorder) is a risk factor for later development of psychiatric conditions, particularly depressive and anxiety disorders.

Clinicians who evaluate and treat children with ADHD frequently report sleep disturbances, especially difficulty initiating sleep and restless and disturbed sleep.62 Surveys of parents and children with ADHD consistently report an increased prevalence of sleep problems, including delayed sleep onset, poor sleep quality, restless sleep, frequent night awakenings, and shortened sleep duration, although more objective methods of examining sleep and sleep architecture (e.g., polysomnography, actigraphy) have overall disclosed minimal or inconsistent differences between children with ADHD and controls. Sleep problems in children with ADHD are likely to be multifactorial in nature, and potential causes range from psychostimulant-mediated sleep-onset delay in some children to bedtime resistance related to a comorbid anxiety or oppositional defiant disorder in others. In some children, difficulties in settling down at bedtime may be related to deficits in sensory integration associated with ADHD, whereas in others, a circadian phase delay may be the primary etiological factor in bedtime resistance. Difficulty falling asleep related to psychostimulant use may respond to adjustments in the dosing schedule, inasmuch as in some children, the sleep onset delay results from a rebound effect of the medication’s wearing off that coincides with bedtime, rather than a direct stimulatory effect of the medication itself. From a clinical standpoint, therefore, an important treatment goal in managing the individual child with ADHD should be evaluation of any comorbid sleep problems, followed by appropriate, diagnostically driven behavioral and/or pharmacological intervention.

Children with Chronic Medical Disorders

Relatively few data currently exist with regard to the effect on sleep problems of both acute and chronic health conditions such as asthma, diabetes, sickle cell disease, and juvenile rheumatoid arthritis in children.63–66 However, particularly in chronic pain conditions, these interactions are likely to significantly affect morbidity and quality of life. A number of patient and environmental factors, such as the effects of repeated hospitalization, family dynamics, underlying disease processes, comorbid mood and anxiety disorders, and concurrent medications, are clearly important to consider in assessing the bidirectional relationship of insomnia and chronic illness in children. Specific medical conditions that may also increase risk of sleep problems include allergies and atopic dermatitis, migraine headaches, seizure disorders, other rheumatological conditions such as chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia, and chronic gastrointestinal disorders such as inflammatory bowel disease. For example, research indicates that one third of asthmatic children report at least one awakening per night,1 and questionnaire-based studies have revealed that asthmatic children rate themselves as significantly more tired in the morning than do normal controls.1 In pediatric populations, research has suggested that pain is positively correlated with sleep disturbances, and that children with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis report greater sleep anxiety, more awakenings per hour, and more daytime sleepiness than do normal controls.

In addition, many over-the-counter and prescription drugs have potentially significant effects on sleep and alertness in children, including direct pharmacological effects, disruption of sleep patterns (e.g., night awakenings), exacerbation of a primary sleep disorder (e.g., OSAS or RLS), withdrawal effects, and daytime sedation.67 Drugs commonly used in children that may have effects on sleep include psychotropic drugs such as stimulants (amphetamines and methylphenidate may cause increased wakefulness and increased sleep onset latency) and antidepressants (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are often activating, and there are frequent reports of sleep disruption; tricyclic antidepressants suppress slow-wave sleep and may cause daytime sedation); antihistamines (first-generation drugs such as diphenhydramine, hydroxyzine, and chlorpheniramine cross the blood-brain barrier and promote sleep; they may also significantly reduce daytime alertness and impair performance); corticosteroids (which may be associated with insomnia and subjective increases in wakefulness); opioids (which may cause daytime sedation and disruption of sleep continuity and may worsen obstructive sleep apnea; their abrupt discontinuation may lead to insomnia and nightmares); and anticonvulsants (which may cause excessive daytime sedation). Also, caffeine, the most widely used drug in the world, has potent effects on sleep, resulting in difficulty initiating sleep and more frequent arousals.

A wide variety of medications have been prescribed or recommended by pediatric practitioners for sleep disturbances in children, including antihistamines, chloral hydrate, barbiturates, phenothiazines, tricyclic antidepressants, benzodiazepines, and α-adrenergic agonists.68,69 In addition, over-the-counter medication such as diphenhydramine and melatonin and herbal preparations are frequently used by parents to treat sleep problems, with or without the recommendation of the primary care provider. The prescription of a wide array of medications for childhood sleep disturbances appears to be based largely on clinical experience, empirical data derived from studies on adults, or small case series of medication use, inasmuch as no medications are currently approved for use as hypnotics in children by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Although a combination of behavioral and pharmacological intervention may be appropriate in selected clinical situations and in specific populations (e.g., children with ADHD, autism spectrum disorders) to treat symptoms of insomnia in children and adolescents, most sleep disturbances in children are successfully managed with behavior therapy alone.

IMPLICATIONS FOR CLINICAL CARE AND RESEARCH

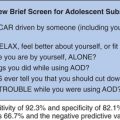

Every child who presents with mood, learning, or behavioral issues should be screened for sleep problems. Parents and the children themselves may not recognize the connection between behavioral and learning disorders and sleep problems and thus may fail to spontaneously volunteer such information. Furthermore, because parents of older children and adolescents, in particular, may not be aware of any existing sleep difficulties, it is also important to question the patient directly about sleep issues. A number of parent-report sleep surveys for use in primary care settings exist, as do several clinical screening tools. The latter category includes a simple tool known by its acronym, BEARS: Key areas of inquiry are: bedtime resistance/delayed sleep onset; excessive daytime sleepiness (e.g., difficulty in morning awakening, drowsiness); awakenings during the night; regularity, pattern, and duration of sleep; and snoring and other symptoms of sleep-disordered breathing.70

If a sleep problem is identified, a comprehensive evaluation includes assessment of current sleep patterns, usual sleep duration, and sleep-wake schedule, often best assessed with a sleep diary in which parents record daily sleep behaviors for an extended period (2 to 4 weeks). A review of sleep habits, such as bedtime routines, daily caffeine intake, and the sleeping environment (e.g., temperature, noise level) may reveal environmental factors that contribute to the sleep problems. Use of additional diagnostic tools such as polysomnographic evaluation are seldom warranted for routine evaluation but may be appropriate if organic sleep disorders such as OSAS or PLMD are suspected. Finally, referral to a sleep specialist for diagnosis and/or treatment should be considered in children or adolescents with persistent or severe bedtime issues that are not responsive to simple behavioral measures or that are extremely disruptive.71

In view of the complexity of the relationship between sleep and mood, attention, learning, and behavior, further research is clearly needed. Key research areas include the neuroanatomical and neurophysiological basis for the relationship between the regulation of sleep and the regulation of mood, attention, and arousal; the relationship between primary sleep disorders, such as obstructive sleep apnea and RLS/PLMD, and symptoms of hyperactivity and inattention in children and adolescents, including identification of risk factors for irreversible central nervous system deficits; elucidation of the scope, magnitude, natural history, and effect on morbidity of sleep disturbances in children and adolescents with behavioral and developmental disorders in comparison with the general population; the efficacy of various treatment modalities for sleep problems in children, including behavioral interventions and pharmacotherapy, and the effect of treatment on the natural history of neurodevelopmental disorders into adulthood; and the potential utility of sleep problems in predicting the eventual emergence of psychiatric comorbid conditions (depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder). Further elucidation of these fundamental questions regarding the nature of the relationship between sleep and mood/learning/behavior will contribute significantly to the understanding of the relationship between specific brain functions, neuromodulator systems, sleep, and daytime behavior. The ultimate goal is to guide clinicians, parents, and patients in the identification of children with neurobehavioral and neurocognitive manifestations of primary sleep disorders, as well as in the management of sleep problems in children with developmental disorders and behavioral conditions.

1 Mindell JA, Carskadon MA, Owens JA. Developmental features of sleep. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1999;8:695-725.

2 Iglowstein I, Jenni O, Molinari L, Largo R. Sleep duration from infancy to adolescence: Reference values and generational trends. Pediatrics. 2003;111:302-307.

3 Jenni O, O’Connor B. Children’s sleep: An interplay between culture and biology. Pediatrics. 2005;115(1 Suppl):204-216.

4 Sheldon S, Kryger MH, Ferber R, editors. Principles and Practices of Pediatric Sleep Medicine. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2005.

5 Mindell J, Owens J. A Clinical Guide to Pediatric Sleep: Diagnosis and Management of Sleep Problems in Children and Adolescents. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2003.

6 Goodlin-Jones B, Burnham M, Gaylor E, et al. Night-waking, sleep-wake organization, and self-soothing in the first year of life. J Dev Behav Ped. 2001;22:226-233.

7 Hiscock H, Wake M. Infant sleep problems and post natal depression: A community based study. Pediatrics. 2001;107:1317-1322.

8 Zuckerman B, Stevenson J, Bailey V. Sleep problems in early childhood: Continuities, predictive factors, and behavioural correlates. Pediatrics. 1987;80:664-671.

9 Kuhn B, Weidinger D. Interventions for infant and toddler sleep disturbance: A review. Child Fam Behav Ther. 2000;22(2):33-50.

10 Katari S, Swanson MS, Trevathan GE. Persistence of sleep disturbances in preschool children. J Pediatr. 1987;110:642-646.

11 LeBourgeois M, Giannotti F, Cortesi F, et al. The relationship between reported sleep quality and sleep hygiene in Italian and American adolescents. Pediatrics. 2005;115(1 Suppl):257-265.

12 Kerr S, Jowett S. Sleep problems in preschool children: A review of the literature. Child Care Health Dev. 1994;20:379-391.

13 Blader JC, Koplewicz HS, Abikoff H, et al. Sleep problems of elementary school children. A community study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997;151:473-480.

14 Owens J, Spirito A, Mguinn M, et al. Sleep habits and sleep disturbance in school-aged children. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2000;21:27-36.

15 Carskadon MA, Wolfson AR, Acebo C, et al. Adolescent sleep patterns, circadian timing, and sleepiness at a transition to early school days. Sleep. 1998;21:871-881.

16 Carskadon MA, Vieira C, Acebo C. Association between puberty and delayed phase preference. Sleep. 1993;16:258-262.

17 Wolfson AR, Carskadon MA. Sleep schedules and daytime functioning in adolescents. Child Dev. 1998;69:875-887.

18 Giannotti F, Cortesi F. Sleep patterns and daytime functions in adolescents: An epidemiological survey of Italian high-school student population. In: Carskadon MA, editor. Adolescent Sleep Patterns: Biological, Social and Psychological Influences. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

19 Fallone G, Owens J, Deane J. Sleepiness in children and adolescents: Clinical implications. Sleep Med Rev. 2002;6:287-306.

20 Smedje H, Broman JE, Hetta J. Associations between disturbed sleep and behavioural difficulties in 635 children aged six to eight years: A study based on parent’s perceptions. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;10:1-9.

21 Dahl RE. The regulation of sleep and arousal: Development and psychopathology. Dev Psychopathol. 1996;8:3-27.

22 Randazzo AC, Muehlbach MJ, Schweitzer PK, et al. Cognitive function following acute sleep restriction in children ages 10–14. Sleep. 1998;21:861-868.

23 Ali NJ, Pitson D, Stradlin JR. Natural history of snoring and related behaviour problems between the ages of 4 and 7 years. Arch Dis Child. 1994;71:74-76.

24 Gozal D. Sleep-disordered breathing and school performance in children. Pediatrics. 1998;102:616-620.

25 Ali NJ, Pitson D, Stradlin JR. Sleep disordered breathing; effects of adenotonsillectomy on behavior and psychological function. Eur J Pediatr. 1996;155:56-62.

26 Gozal D, Pope D. Snoring during early childhood and academic performance at ages thirteen to fourteen years. Pediatrics. 2001;107:1394-1399.

27 Chervin RD, Dillon JE, Bassetti C, et al. Symptoms of sleep disorders, inattention, and hyperactivity in children. Sleep. 1997;20:1185-1192.

28 Picchietti D. Periodic limb movement disorder and restless legs syndrome in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Child Neurol. 1988;13:588-594.

29 Picchietti D, Walters A. Restless legs syndrome and period limb movement disorders in children and adolescents. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1996;5:729-740.

30 Walters AS, Mandelbaum DE, Lewin DS, et al. Dopaminergic therapy in children with restless legs/periodic limb movements in sleep and ADHD. Dopaminergic Therapy Study Group. Pediatr Neurol. 2000;22:182-186.

31 Valent F, Brusaferro S, Barbone F. A case-crossover study of sleep and childhood injury. Pediatrics. 2001;107:E23.

32 Mindell JA, Durant VM. Treatment of childhood sleep disorders: Generalization across disorders and effects on family members. Special issue: Interventions in pediatric psychology. J Pediatr Psychol. 1993;18:731-750.

33 Marcus CL. Sleep-disordered breathing in children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:16-30.

34 Schecter M, Section on Pediatric Pulmonology, Subcommittee on Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome. AAP technical report: Diagnosis and management of childhood obstructive sleep apnea. Pediatrics. 2002;109(4):e69.

35 Section on Pediatric Pulmonology, Subcommittee on Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome, American Academy of Pediatrics. Clinical practice guideline: Diagnosis and management of childhood obstructive sleep apnea. Pediatrics. 2002;109:704-712.

36 Lipton AJ, Gozal D. Treatment of obstructive sleep apnea in children: Do we really know how? Sleep Med Rev. 2003;7(1):61-80.

37 Guilleminault C, Palayo R, Leger D, et al. Recognition of sleep disordered breathing in children. Pediatrics. 1996;98:871-882.

38 Lalakea ML, Marquez-Biggs I, Messner AH. Safety of pediatric short-stay tonsillectomy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;125:749-752.

39 Waters KA, Everett FM, Bruderer JW, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea: The use of nasal CPAP in 80 children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:780-785.

40 Marcus CL, Ward SL, Mallory GB, et al. Use of nasal continuous positive airway pressure as treatment of childhood obstructive sleep apnea. J Pediatr. 1995;137:88-94.

41 Mahowald MW. Arousal and sleep-wake transition parasomnias. In: Lee-Chiong T, Sateia MJ, Carskadon MA, editors. Sleep Medicine. Philadelphia: Hanley & Belfus, 2002. Chapter 24

42 Laberge L, Trembly RE, Vitaro F, et al. Development of parasomnias from early childhood to early adolescence. Pediatrics. 2000;106:67-74.

43 Rosen GM, Mahowald MW. Disorders of arousal in children. In: Sheldon S, Kryger MH, Ferber R, editors. Principles and Practices of Pediatric Sleep Medicine. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2005:293-304.

44 Sheldon SH, Glaze DG. Sleep in neurologic disorders. In: Sheldon S, Kryger MH, Ferber R, editors. Principles and Practices of Pediatric Sleep Medicine. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2005:269-292.

45 Sheldon SH. The parasomnias. In: Sheldon S, Kryger MH, Ferber R, editors. Principles and Practices of Pediatric Sleep Medicine. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2005:305-315.

46 Tabbal SD. Restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder. In: Lee-Chiong T, Sateia MJ, Carskadon MA, editors. Sleep Medicine. Philadelphia: Hanley & Belfus, 2002. Chapter 26

47 Wise MS. Childhood narcolepsy. Neurology. 1998;50(Suppl 1):S37-S42.

48 Kotagal S, Hartse K, Walsh J. Characteristics of narcolepsy in pre-teenaged children. Pediatrics. 1990;82:205-209.

49 Dahl R, Holtum J, Trubnick L. A clinical picture of child and adolescent narcolepsy. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1994;33:834-841.

50 Garcia J, Rosen G, Mahowald M. Circadian rhythms and circadian rhythm disturbances in children and adolescents. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2001;8:229-240.

51 Sack RL, Lewy AJ, Highes RJ. Use of melatonin for sleep and circadian rhythm disorders. Ann Med. 1998;30:115-121.

52 The International Classification of Sleep Disorders. Diagnosis and Coding Manual (ICSD-2), 2nd ed. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2005.

53 Mindell J, Kuhn B, Lewin D, et al. Behavioral treatment of bedtime problems and night wakings in infants and young children. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Review. Sleep. 2006;29:1263-1276. Sleep. 2006;29:1380. [erratum in:]

54 Hohagen F. Nonpharmacologic treatment of insomnia. Sleep. 1996;19:S50-S51.

55 Wiggs L. Sleep problems in children with developmental disorders. J Royal Soc Med. 2001;94:177-179.

56 Johnson C. Sleep problems in children with mental retardation and autism. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1996;5:673-681.

57 Didden R, Curfs LMG, van Driel S, et al. Sleep problems in children and young adults with developmental disabilities: Home-based functional assessment and treatment. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2002;33:49-58.

58 Jan MMS. Melatonin for the treatment of handicapped children with severe sleep disorders. Pediatr Neurol. 2000;23:229-232.

59 Sadeh A, McGuire JP, Sachs H. Sleep and psychological characteristics of children on a psychiatric inpatient unit. J Am Acad of Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;33:1303-1346.

60 Sachs H, McGuire J, Sadeh A, et al. Cognitive and behavioural correlates of mother reported sleep problems in psychiatrically hospitalized children. Sleep Res. 1994;23:207-213.

61 Dahl RE, Ryan ND, Matty MK, et al. Sleep onset abnormalities in depressed adolescents. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;39:400-410.

62 Owens J. The ADHD and sleep conundrum: A review. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2005;26:312-322.

63 Rose M, Sanford A, Thomas C, et al. Factors altering the sleep of burned children. Sleep. 2001;24:45-51.

64 Lewin D, Dahl R. Importance of sleep in the management of pediatric pain. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1999;20:244-252.

65 Bloom B, Owens J, McGuinn M, et al. Sleep and its relationship to pain, dysfunction and diseases activity in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:169-173.

66 Sadeh A, Horowitz I, Wolach-Benodis L, et al. Sleep and pulmonary function in children with well-controlled stable asthma. Sleep. 1998;21:379-384.

67 Mindell J, Owens J. Sleep and medications. In: A Clinical Guide to Pediatric Sleep: Diagnosis and Management of Sleep Problems. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003:169-182.

68 Owens J, Rosen C, Mindell J. Medication use in the treatment of pediatric insomnia: Results of a survey of community-based pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2003;111(5):e628-e635.

69 Owens J, Babcock D, Blumer J, et al. The use of pharmacotherapy in the treatment of pediatric insomnia in primary care: Rational approaches. A consensus meeting summary. J Clin Sleep Med. 2005;1:49-59.

70 Owens J, Dalzell V. Use of the “BEARS” sleep screening tool in a pediatric residents’ continuity clinic: A pilot study. Sleep Med. 2005;6:63-69.

71 Kryger M. Differential diagnosis of pediatric sleep disorders. In: Sheldon S, Kryger MH, Ferber R, editors. Principles and Practices of Pediatric Sleep Medicine. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2005:17-25.