25

Sexual problems

Introduction

It is important for any doctor to be able to take a sexual history and to have some idea of how sexual problems are managed. Understanding the physiology of the normal sexual response will allow the doctor to better understand many of the uncomplicated sexual problems.

Scientific investigation of the normal sexual response is necessary to our understanding, but, because of society’s disapproval, few scientists have chosen to work in this area until recently. Early workers were:

![]() Sigmund Freud (1856–1939), an Austrian doctor, was the founder of psychoanalysis and the first to recognize the importance of childhood influences on sexuality. His studies were on patients rather than normal subjects.

Sigmund Freud (1856–1939), an Austrian doctor, was the founder of psychoanalysis and the first to recognize the importance of childhood influences on sexuality. His studies were on patients rather than normal subjects.

![]() Havelock Ellis (1859–1939) studied medicine at St Thomas’s Hospital, London. His seven-volume Studies in the Psychology of Sex (1897–1928) caused controversy but was the first detached treatment of the subject.

Havelock Ellis (1859–1939) studied medicine at St Thomas’s Hospital, London. His seven-volume Studies in the Psychology of Sex (1897–1928) caused controversy but was the first detached treatment of the subject.

![]() Alfred Kinsey (1894–1956), an American zoologist, became director of Indiana University’s Institute for Sex Research in 1942. To investigate ‘normal’ sexual experience, 18 500 Americans were interviewed. Sexual Behaviour in the Human Male was published in 1948, and Sexual Behaviour in the Human Female in 1953.

Alfred Kinsey (1894–1956), an American zoologist, became director of Indiana University’s Institute for Sex Research in 1942. To investigate ‘normal’ sexual experience, 18 500 Americans were interviewed. Sexual Behaviour in the Human Male was published in 1948, and Sexual Behaviour in the Human Female in 1953.

![]() Masters and Johnson: William Masters (1915–2001), a doctor, and Virginia Johnson (1925–2013), a psychologist, working at Washington University, St Louis, carried out the first direct observations on sexual activity under laboratory conditions. Human Sexual Response appeared in 1966, and Human Sexual Inadequacy in 1970.

Masters and Johnson: William Masters (1915–2001), a doctor, and Virginia Johnson (1925–2013), a psychologist, working at Washington University, St Louis, carried out the first direct observations on sexual activity under laboratory conditions. Human Sexual Response appeared in 1966, and Human Sexual Inadequacy in 1970.

![]() The field of sexual medicine or sexology has developed significantly since the early work of these pioneers and is now a flourishing specialty in itself. There are numerous societies, conferences and journals devoted to the field. Despite this, it is still a super specialism and not everyone has access to services for sexual problems.

The field of sexual medicine or sexology has developed significantly since the early work of these pioneers and is now a flourishing specialty in itself. There are numerous societies, conferences and journals devoted to the field. Despite this, it is still a super specialism and not everyone has access to services for sexual problems.

Normal sexual response

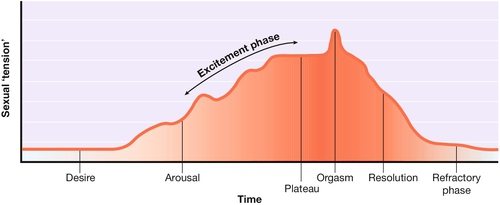

The normal human sexual response can be regarded as having five phases: desire, arousal, orgasm, resolution and the refractory phase (Fig. 25.1).

Desire

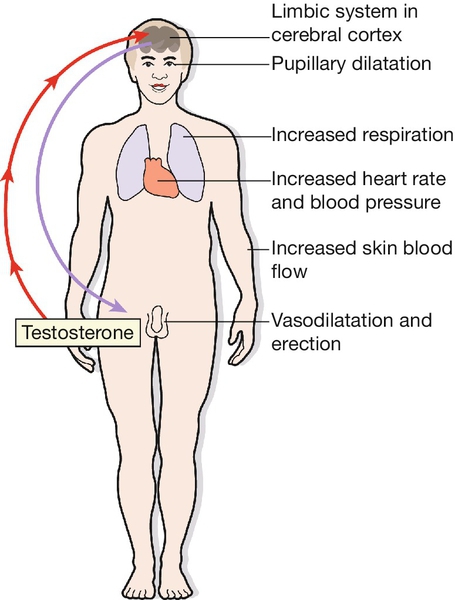

Sexual desire refers to the general level of interest in sexuality. It is modulated by hormones – hence the change in sexual interest at puberty. The main hormonal modulator in both sexes is testosterone. Desire is also dependant on contextual factors such as mood, environment and levels of sexual attraction.

Arousal

This phase has three components: central arousal, genital response and peripheral arousal.

Central arousal

This refers to the response to sexual stimuli, which may be visual or tactile or may result from internal imagery or from a relationship. These stimuli act through the cerebral cortex (Fig. 25.2). The areas of the brain involved in sexual arousal are thought to be in the limbic system. There are thought to be excitatory centres with endorphins as the neurotransmitter, and inhibitory centres, linked to the centres for pain and fear.

Genital response

The spinal pathways leading to the genitalia are not precisely known but appear to be near the spinothalamic pathways for pain and temperature. Genital responses are due to vasocongestion and neuromuscular changes. Arteriolar dilatation is probably controlled by the parasympathetic sacral outflow at S2, 3 and 4 via the nervi erigentes. Thoracic sympathetic outflow also plays a part. The local neurotransmitters involved include vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP), a potent vasodilator found in the penis and vagina.

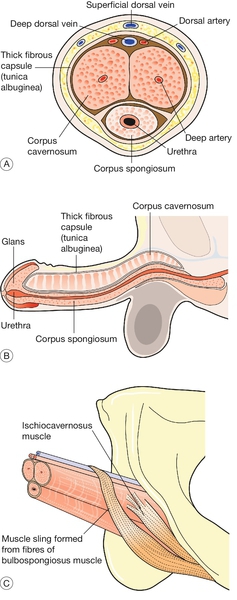

In the male, engorgement of the corpora cavernosa is due mainly to arteriolar dilatation and probably a reduction in the venous outflow which results in penile erection (Fig. 25.3). The scrotum tightens due to contraction of the dartos muscle and the testes are elevated due to contraction of the cremaster muscle.

(A) Cross-section showing erectile spaces and principal blood vessels. (B) Erectile tissues. Each crus of the corpora cavernosa is inserted into the pubic bone. (C) Muscles.

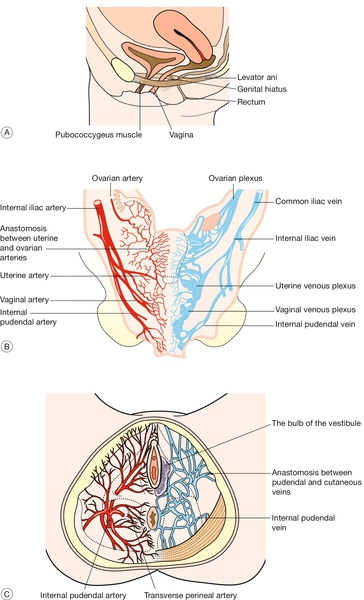

In the female, there is engorgement of the venous plexus surrounding the lower part of the vagina, and of the erectile bulbs of the vestibule on either side of the introitus (Fig. 25.4). There is reddening and pouting of the labia minora. The clitoris becomes erect and later is said to retract against the symphysis pubis.

Fig. 25.4Female reproductive organs.

(A) The muscular supports of the vagina. This shows the sling of muscle fibres that surround the urethra, vagina and rectum, running from the pubic bone to the coccyx. The levator plate formed by these fibres supports the rectum and vagina in its non-aroused horizontal position. (B) Arteries and veins supplying the female reproductive organs. (C) Blood vessels of the pelvic floor, showing the rich arterial and venous networks surrounding the vaginal opening.

The vagina becomes lubricated by a transudate as the blood supply to the vaginal wall increases. This fluid is not the product of mucous glands: beads of fluid appear all over the vaginal wall. Mucus secretion from the cervix makes relatively little contribution to vaginal lubrication (which is therefore usually unaffected by hysterectomy). Secretion from Bartholin’s glands, formerly thought to be mainly responsible for lubrication, is only moderate in amount and occurs relatively late during arousal.

Relaxation of the woman’s pelvic floor muscles occurs after vaginal lubrication has started. In the later stages of arousal, the uterus becomes engorged, increases in size and rises in the pelvis. The upper part of the vagina ‘balloons’ and there may be slow irregular contractions of the lower third of the vagina.

In both sexes, but particularly in the male, the genital response interacts with the central response, so that arousal becomes self-amplifying.

Peripheral arousal

Sexual arousal causes:

![]() a rise in systolic and diastolic blood pressure (which may only be transient)

a rise in systolic and diastolic blood pressure (which may only be transient)

![]() general flushing of the skin

general flushing of the skin

![]() change in heart rate (either an increase or a decrease)

change in heart rate (either an increase or a decrease)

![]() respiratory changes

respiratory changes

![]() pupillary dilatation.

pupillary dilatation.

Plateau phase

When arousal is complete, there may be a ‘plateau’ phase during which the couple prolong the pleasure of intercourse before orgasm. If this continues too long, however, coitus may become painful for one or both partners.

Orgasm

Orgasm involves genital, muscular and sensory changes, as well as cardiovascular and respiratory responses.

In the male

First, there is smooth muscle contraction of the epididymis, vas deferens, seminal vesicle, prostate and ampulla, propelling seminal and prostatic fluid into the urethral bulb. Then, the male becomes aware that orgasm is imminent and ejaculation usually follows within a few seconds. The internal bladder sphincter remains shut but the external sphincter relaxes and semen is propelled along the urethra by rhythmic contractions of the bulbospongiosus and ischiocavernosus muscles.

In the female

A few seconds after the onset of the subjective experience of orgasm, there is a spasm of the muscles surrounding the lower third of the vagina (the ‘orgasmic platform’) followed by a series of rhythmic contractions, usually five to eight in number. These do not expel fluid from the vagina. Uterine contractions may also occur.

In both sexes

There is contraction of rectus abdominis, pelvic thrusting, contraction of the anal sphincter and sometimes carpopedal spasm. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure rises by at least 25 mmHg, and hyperventilation occurs. There is a feeling of intense pleasure and an alteration of consciousness to a variable degree.

Resolution

The events of arousal are gradually reversed. In men, there is a moderate immediate loss of erection, followed by a slower complete reversal. In women, if no orgasm has occurred, pelvic congestion may take hours to resolve and may be uncomfortable. In both sexes, there is a subjective feeling of relaxation, though its duration may differ between the man and the woman.

Refractory phase

There follows an interval during which further stimulation does not produce a response. In men, this varies from minutes in young men to many hours in older men. Some women do not experience a refractory period, only a minority of women (14% according to Kinsey) can have multiple orgasms.

The effect of age

Normal sexual behaviour differs from couple to couple. It also alters with age and with the evolution of a sexual relationship. Patients may present with problems due to difficulties in adjusting to the change from one phase to the next of a relationship.

Adolescence

An adolescent usually has a higher capacity for sexual arousal and a need to discover their sexual attractiveness. However, coupled with the need to learn about sexual behaviour there is an emotional vulnerability. Unsatisfactory sexual experience at this time can result in continuing problems later as a result. Young women in their teens are at a higher risk of unwanted pregnancy due to uncertainty about contraceptive needs.

The couple

The early months of a relationship may be characterized by frequent sex, but couples need to learn quickly how to establish good communication and to adjust their sexual behaviour to suit each other’s needs, as desire usually wanes as a relationship progresses. Should this communication not occur, dysfunctional patterns may develop potentially resulting in sexual problems and relationship difficulties.

Early parenthood

The time taken for sexual interest to return after childbirth is variable and in some women, can be a year or more. Problems can result from a difficult birthing experience or postnatal depression but more commonly are due to tiredness and the difficulties coping with the demands of the new baby.

Middle age

When the novelty of a sexual relationship has worn off, sexual activity usually becomes less frequent and this may cause anxieties. Couples may feel they ‘ought’ to be having sex more often. Stresses at work for both partners in combination with social commitments can make it difficult for them to find time to relax together. In the years before the menopause, women often have menstrual problems. After the menopause, there may be a reduction in sexual interest or a problem with vaginal dryness; these can usually be corrected by hormone replacement therapy.

Old age

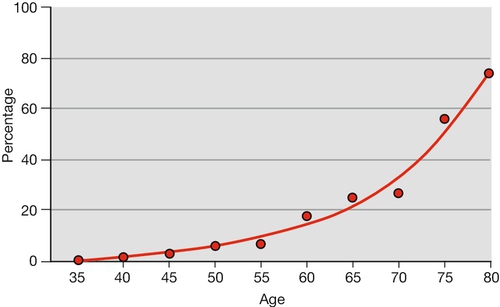

There is a decline in erectile function with age, which can be a manifestation of physical disease (Fig. 25.5). Postmenopausal women may experience low libido and vaginal dryness or atrophy. These factors can impact on the couple’s sexual relationship.

The functions of sex

It is important to remember how much people differ from one another and how wide the range of normality may be.

Reproduction

Reproductive sex is often limited to a short interval in a couple’s relationship once conception has occurred. Couples who have fertility problems may find that it causes difficulty with their sex life, or conversely may find, that after they achieve pregnancy it is difficult to have sex for pleasure only.

Physical Exercise

Sexual activity is a form of physical exercise, which improves self-esteem and feelings of well-being but is also something to bear in mind in people with physical problems, such as angina.

Pleasure

Though sex is readily associated with pleasure, there are in some cultures taboos that prevent some people from enjoying sex.

Pair-bonding

Enjoying sex means lowering one’s defences, and sharing this experience strengthens the bond between partners. People who have had to build particularly strong defences, for example, after emotional abuse in childhood, may have difficulty in relinquishing them.

Asserting masculinity or femininity

People may use sexual activity to reassure themselves about their sexuality.

Bolstering self-esteem

Satisfactory sex can improve one’s self-esteem however, for some, promiscuous behaviour to accomplish this can have negative consequences.

Achieving power

Some people see the sexual relationship in terms of dominance and submission. This can apply to coitus itself, or to the power to allow or deny access to sex. Rape can be seen as an example of this.

Reducing anxiety or tension

This can be helpful for most people but in some cases, can cause relationship or personal problems through risk taking, for example, promiscuity or use of internet pornography.

Material gain

Prostitution is the most obvious form of sex for gain, and is often the result of poverty. Marriage, even nowadays, may also be a way of using sex to buy security.

History-taking

Some sexual problems may present as another symptom such as pelvic pain, or are discovered fortuitously, for example, when a routine enquiry is made about contraception. It is not possible to take a detailed sexual history from every patient whatever their complaint, but it is reasonable, particularly in a gynaecological clinic, to ask one or two questions about sex as a routine; for example, ‘Do you have any trouble with intercourse?’ or, if appropriate, ‘Is this symptom worse after intercourse?’ An evasive reply may suggest that all is not well which may require some further sensitive questioning.

Elucidating a sexual problem relies mainly on the history, although useful information may be obtained from examination or investigation. The interviewer should be comfortable with the subject, as the patient is likely to be embarrassed by talking about a sexual problem. A sympathetic but matter-of-fact approach may help to reduce this embarrassment. The vocabulary used must also be appropriate, using words that avoid, on the one hand, being too technical and, on the other hand, appearing too crude.

It is usually helpful to see both partners, but not necessarily together on the first occasion. A patient may be more open if interviewed alone, but the partner may give quite a different version of the history. When treatment is planned, however, both partners should ideally be involved.

The history needs to be thorough, but, if too intrusive, it may be off-putting. If a topic seems painful, the subject can be changed and then returned to later. Sometimes more than one interview is necessary, with sensitive topics being explored on the second occasion after a rapport has been established. A detailed account of a specific instance may be more helpful than asking general questions. For example, if the patient is asked ‘How often do you have intercourse?’ the reply is likely to depend partly on what the patient thinks is expected (e.g. ‘About twice a week’). It may be better to ask ‘When did you last have intercourse?’, and then, if the couple’s last attempt was unsatisfactory, to ask in detail about what went wrong. Open questions should also be used, for example, ‘How did you feel when that happened?’

Many patients, especially if talking about their sexual problem for the first time, find it difficult to put their feelings into words. It may be helpful to offer the occasional summary: ‘What I think you’re saying is that …’. The patient will usually give a clearly positive response if the doctor has summed up the situation correctly. If the patient’s response is more guarded, the doctor should be cautious about the conclusions drawn.

Human sexuality

There are several variations of human sexuality which should not be seen as problems unless they are presented as such by the patient. Most people are heterosexual or straight in that they are attracted to a sexual partner of the opposite gender. Some of the more common variations are detailed below.

Homosexuality

This refers to being attracted to a partner of the same gender. Homosexuality or being ‘gay’ is widely accepted in most societies but in some cultures, there remains a degree of stigma which can be difficult for the homosexual person to cope with. This can result in mental health problems in some cases.

Transsexualism

A transsexual is a man or woman who believes they are of the opposite gender in spite of their anatomy. This is a condition of gender identity not sexual identity and a variety of sexual identities can be encountered. Transsexuals are likely to seek medical help to alter their bodies to be consistent with their psychological gender identity. Usually, these people require treatment from a variety of specialists including psychiatrists, endocrinologists and surgeons to ‘transition’ or change to the opposite gender. Most transsexuals feel better after transition but they are still subject to discrimination in some cultures.

Transvestitism

A transvestite is someone who enjoys dressing in the clothes of the opposite gender. This is usually associated with sexual excitement and is not associated with a desire to change their gender. Most of these patients are male and rarely present to services unless their behaviour causes relationship difficulties.

Sadomasochism

This is a spectrum of sexual behaviours encompassed in the term, ‘BDSM’ (bondage, discipline, sadism and masochism), which involve mild to extreme pain being inflicted or received for sexual pleasure. It is unusual for these people to present to services unless they are traumatised either physically or psychologically by their practices or their behaviour results in injury to another person and possibly legal action.

Fetishism

Particular parts of the body, articles of clothing (e.g. shoes) or materials (e.g. rubber or plastic) can become objects of sexual gratification.

Paedophilia

This term refers to a sexual preference for children usually of prepubertal age. This is an illegal practice and adults engaging in this behaviour should be reported if it is apparent that they are engaging in this behaviour. This is an instance when medical confidentiality should be breached.

Sexual dysfunction

Sexual dysfunction may be due to psychological or relationship problems or may have a medical or surgical cause. Sexual dysfunction is common, with 43% of women and 31% of men experiencing some form of sexual dysfunction during their lifetime.

The common disorders of sexual function can be classified according to the physiological stages described early in this chapter:

![]() impaired desire

impaired desire

![]() disorders of arousal

disorders of arousal

![]() disorders of orgasm

disorders of orgasm

![]() dyspareunia.

dyspareunia.

The causes of sexual dysfunction can be classified into physiological or psychological factors but it is hard to make a distinction between the two as they often coexist. For example, painful intercourse due to a physical cause such as a herpetic lesion may lead to secondary anxiety in both partners. However, anxiety due to sexual abuse in childhood may lead to spasm of the pelvic floor muscles. Treatment often needs to be directed towards physical and psychological causes at the same time.

A list of pathological causes of sexual dysfunction is given in Box 25.1. These causes are more common in older people. Psychological causes of sexual dysfunction are given in Box 25.2.

Female sexual dysfunction

Impaired desire

This is a common presentation to specialist sexual medicine clinics, although it is not such a frequent symptom in routine gynaecology clinics. The woman complains that she is just not interested in sex. Such ‘loss of libido’ may be primary or secondary.

Primary

Some women have never felt interested in sex and in these cases, there is usually impairment of arousal and orgasm as well. The underlying cause is often psychological. A woman may try to choose a partner who also has an apparently low sex drive to match her desire.

Secondary

More commonly, loss of libido follows an interval of apparently normal sex drive, during the woman’s teens or early 20s, or early in the relationship with her partner. Loss of interest in sex may occur after childbirth, when both parents devote all their attention to the baby, often combining motherhood with a return to paid employment. If there has been postnatal depression, this will exacerbate the problem.

Other causes include:

![]() depression

depression

![]() bereavement

bereavement

![]() the menopause, medical causes or drugs (Box 25.1)

the menopause, medical causes or drugs (Box 25.1)

![]() gynaecological investigation, e.g. for an abnormal cervical smear

gynaecological investigation, e.g. for an abnormal cervical smear

![]() loss of self-esteem, e.g. problems at work.

loss of self-esteem, e.g. problems at work.

Sometimes, the secondary loss of libido has no obvious specific cause. A woman who has suffered sexual or physical abuse in childhood, or who has had a sexually repressed upbringing, may go through a phase of normal or increased sexual activity in her teens and 20s and then present with loss of libido due to the long-term effects of her childhood experiences.

Often, a man reacts to the woman’s loss of interest by making persistent sexual demands and then, after some years, giving up approaching her for sex. Loss of desire is often due to a problem with the relationship, and counselling will be directed towards improving communication between the partners. A specific cause, such as childhood abuse, may require specialist referral. Hormone therapy is appropriate for postmenopausal women but not for those who still have a normal menstrual cycle.

Orgasmic dysfunction

Inability to achieve orgasm is usually associated with lack of interest in sex, but sometimes can be an isolated symptom in a woman who has an otherwise satisfactory sex drive and is able to experience normal arousal.

Primary

This refers to a woman who has never been orgasmic. Inability to achieve orgasm, despite adequate arousal may be due to inexperience of the woman or her partner, or unrealistic expectations, e.g. reading erotic fiction may have led the couple to believe that orgasm occurs automatically on penetration. Often education and reassurance about normal sexual behaviour is all that is required in these circumstances. Sometimes, the cause is more deep-seated; possibly because of childhood repression, the woman is unable to let go of her defences. Psychological counselling may be helpful in these cases.

Secondary

Secondary orgasmic dysfunction follows an interval of adequate sexual functioning. It is usually associated with reduced desire or arousal, as discussed in the previous section.

Situational orgasmic dysfunction

Some women can achieve orgasm through masturbation but not coitus, or with one partner but not with another. This is usually a pointer towards relationship difficulties.

Vaginismus

Vaginismus is involuntary spasm of the pelvic floor muscles and perineal muscles, provoked by attempted penetration. It is also provoked by vaginal examination or by attempts to insert a tampon or the woman’s own finger into the vagina. When severe, the conditioned reflex includes spasm of the adductor muscles of the thighs.

Primary

In most cases, the problem is primary vaginismus and is discovered during the first attempt at intercourse. It may be due to apprehension that intercourse will be painful or due simply to failure to control the pelvic musculature. Persistent attempts at penetration cause more pain and a ‘vicious circle’ is set up, reinforcing the vaginismus.

Primary vaginismus may also be due to more deep-seated psychological problems, such as an unwillingness to accept sexual maturity, sexual repression in childhood or fear of pregnancy.

Secondary

Vaginismus may also follow a physically painful experience, such as a sexual assault, an obstetric problem at delivery or an insensitive vaginal examination. It can sometimes also result from painful infections or other conditions, e.g. lichen sclerosis, therefore an examination is essential in all patients with vaginismus to exclude organic causes.

Management of vaginismus

The vulva and vagina should be examined for any painful lesion, though in most cases no such cause will be found. In a few cases examination will reveal a firm intact hymen and this may require dilatation under anaesthesia.

Most cases of primary and secondary vaginismus respond well to simple treatment, involving training in relaxation and the use of vaginal dilators/trainers. The woman should be helped to relax completely: she should let her head rest on the pillow and vaginal examination should not be attempted until the adductor muscles of the thighs have fully relaxed. The woman is then taught to insert a small vaginal dilator: such patients need a combination of gentleness and encouragement to overcome their apprehension. Once she is comfortable about inserting the small dilator regularly, she can progress to gradually larger sizes. During treatment, she is also taught pelvic floor exercises, which help her to gain control of the muscles. It may take several weeks or months before full control is achieved.

Attempts at intercourse should be discouraged until she is able to insert the larger-sized vaginal dilators. In most instances, satisfactory intercourse follows. An alternative to vaginal dilators is for the woman to use her own finger and then for the partner to insert one and then two fingers into the vagina. In most instances that present to the clinic, however, the couple are reluctant to do this and prefer the dilators. If primary vaginismus is due to more deep-seated problems, treatment may take many months and the prognosis is less good. Psychosexual counselling may be appropriate in these cases.

For treatment of resistant cases botulinum toxin (Botox) injected into the pelvic muscles can be very effective.

Dyspareunia

Pain on intercourse is the commonest sexual problem presenting to the routine gynaecology clinic. It is usually classified into superficial and deep dyspareunia, but it is not always possible to make a clear distinction between the two (Box 25.3). With superficial dyspareunia, there is a pain at the vaginal introitus on attempted penetration, often making full intercourse impossible. In deep dyspareunia, there is pain in the pelvis on deep penetration. Bimanual examination may reveal a specific area of tenderness, e.g. on moving the cervix or on palpating the posterior fornix, the rectum, or one or other lateral fornix. Sometimes, however, the tenderness is more general and a specific site cannot be identified.

Examination of the vulva may reveal the inflammatory appearance of candidal infection, the lesions of herpes, or the presence of atrophy or dystrophy. Careful examination may be necessary to reveal the localized inflammation of vestibulitis. Vulval and vaginal swabs should be taken for microbiological examination and treatment given if appropriate. If no cause is found for what appears to be superficial dyspareunia, it may be necessary to consider the causes of deep dyspareunia.

Deep dyspareunia is often associated with other symptoms such as dysmenorrhoea or persistent pelvic pain. The history should include questions about bowel habit. Bowel dysfunction is not uncommon and can be treated with a high-fibre diet. The timing of the pain in relation to the cycle should also be noted – it may occur just before ovulation or menstruation. Bimanual examination may reveal a pelvic mass.

The finding of a retroverted uterus is unlikely to be significant, as uterine retroversion is common. Occasionally, however, a sharply retroverted uterus can be the only site of tenderness. High vaginal and cervical swabs should be taken if there is any suspicion of pelvic infection. In most cases, laparoscopy is necessary to diagnose or exclude endometriosis or pelvic inflammatory disease.

When a specific cause is identified, the appropriate treatment is given. If laparoscopy is negative, a high-fibre diet may help even in the absence of obvious bowel symptoms. If no cause is found and the deep dyspareunia is not associated with other symptoms, the problem may be due to limited foreplay, leading to inadequate arousal and insufficient relaxation of the upper vagina. The couple should try allowing more time for arousal, and may be advised to avoid positions (such as the woman sitting on top of the man) in which penetration is particularly deep. Lubricants can be helpful and are worth trying.

If deep dyspareunia is associated with ‘unexplained pelvic pain’, treatment can be difficult and may require a combination of endocrine manipulation and psychological support.

Male sexual dysfunction

Male sexual dysfunction can be classified as impairment of desire, erection or ejaculation. There is considerable overlap between these disorders.

Impaired desire

In the male, libido is dependent on normal testosterone levels, and serum testosterone should be checked in men complaining of lack of libido. If the level is normal, testosterone supplements are unlikely to help.

There is an assumption among many men that they should always be ready for sex. There is also a widespread expectation that medications exist which can increase libido. Male patients are often unwilling or unable to change a busy lifestyle, which leaves little time for sex.

Erectile dysfunction

Inability to achieve or maintain a satisfactory erection (‘impotence’) is the commonest sexual problem among men. It may be associated with impaired desire, but desire usually is normal. Indeed, the anxiety provoked by the erectile dysfunction may increase his awareness of sexual stimuli.

Erectile dysfunction is often due to psychological factors but it is important to investigate possible physical causes. Erectile dysfunction is often the first sign of cardiovascular disease and all patients who present with this symptom should have their cardiovascular risk status assessed. If a physical cause is found, treatment may resolve the problem. The patient may also not accept a diagnosis of a psychological cause until all possible physical causes have been excluded (Box 25.4).

In addition to a full sexual history, the man should be asked about the duration of the problem, whether it is primary or secondary, and whether it is situational (i.e. does he get ‘early morning’ erections, or can he get an erection by masturbation but not with his partner). Enquiry should be made about symptoms of general disease, including those listed above. Smoking history is also important.

Clinical examination should include a check for signs of systemic disease. The genitalia should be examined for abnormalities of the penis (such as hypospadias) or abnormally small testes. Serum testosterone, glucose and lipids should be checked as a matter of routine.

Therapeutic options include:

![]() Phosphodiesterase inhibitors, e.g. sildenafil (Viagra). Penile erection is due to relaxation of the smooth muscle around the cavernosal vascular spaces, allowing them to fill with blood. This is under the control of the autonomic nervous system, mediated by cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP). These drugs are taken orally and enhance erection by blocking breakdown of cGMP. Alternatives to sildenafil are vardenafil (Levitra), which acts more quickly, and tadalafil (Cialis), which has a longer duration of action. They work best in psychogenic erectile failure and milder organic problems, in which the success rate is about 85%. Side-effects are mild and transient and include flushing, dyspepsia, headache and disturbance of colour vision. These drugs must not be used by men who use nitrates or have severe cardiac disease, as they may lead to a life-threatening profound drop in blood pressure.

Phosphodiesterase inhibitors, e.g. sildenafil (Viagra). Penile erection is due to relaxation of the smooth muscle around the cavernosal vascular spaces, allowing them to fill with blood. This is under the control of the autonomic nervous system, mediated by cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP). These drugs are taken orally and enhance erection by blocking breakdown of cGMP. Alternatives to sildenafil are vardenafil (Levitra), which acts more quickly, and tadalafil (Cialis), which has a longer duration of action. They work best in psychogenic erectile failure and milder organic problems, in which the success rate is about 85%. Side-effects are mild and transient and include flushing, dyspepsia, headache and disturbance of colour vision. These drugs must not be used by men who use nitrates or have severe cardiac disease, as they may lead to a life-threatening profound drop in blood pressure.

![]() Alprostadil (PGE1). This drug also relaxes cavernosal smooth muscle but has to be injected directly into the corpora cavernosa. It is more effective than sildenafil in erectile failure. It is also available as a urethral pellet (MUSE) but this is less effective.

Alprostadil (PGE1). This drug also relaxes cavernosal smooth muscle but has to be injected directly into the corpora cavernosa. It is more effective than sildenafil in erectile failure. It is also available as a urethral pellet (MUSE) but this is less effective.

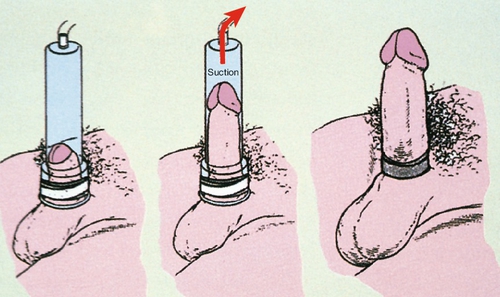

![]() Other treatments used include vacuum devices (Fig. 25.6) and penile implants, the latter only where no other treatment has been effective.

Other treatments used include vacuum devices (Fig. 25.6) and penile implants, the latter only where no other treatment has been effective.

Ejaculatory dysfunction

The most common type of ejaculatory dysfunction is premature ejaculation. Retarded ejaculation is much less common and may be associated with other psychological problems. Painful ejaculation is relatively rare.

Premature ejaculation is normal in early sexual experiences. It is difficult to define, and the best guide is if the man feels he has insufficient control to satisfy himself and his partner. Sometimes, ejaculation occurs before penetration or within a few seconds of penetration. The cause of premature ejaculation is unknown but when it occurs it leads to anxiety and a vicious circle.

Treatment requires the cooperation of the partner and it is difficult to help a man who presents for treatment without his partner’s knowledge. If the couple have a good relationship, they can be instructed in the ‘stop–start’ technique. This is when the couple have sex until just before the point of orgasm then ‘stop’ moving or withdraw the penis until the sensation passes then ‘starting’ again and repeating this. Practice with this technique helps to build a feeling of control. The ‘squeeze’ technique – firm pressure at the level of the frenulum when an orgasm is imminent – may also help to retard ejaculation. Antidepressant drugs (SSRIs e.g. sertraline) are used off license to delay orgasm and are very effective. A small amount of local anaesthetic applied to the frenulum before sex can also be helpful in some cases.

Treatment of sexual problems

The treatment of sexual problems can be divided into two categories:

![]() counselling, which should be within the scope of a general practitioner

counselling, which should be within the scope of a general practitioner

![]() sex therapy, which requires specialist training.

sex therapy, which requires specialist training.

Counselling

Some problems can be helped by a single consultation or a few consultations. Simple counselling may include the items below.

Permission giving

A patient may become very anxious about some activity, such as masturbation, and may be helped to know that it is normal. Simply talking about sexual matters in a matter-of-fact way is helpful to many patients who feel they are unique in experiencing difficulties.

Limited information

An explanation of normal anatomy or physiology may also be helpful. He or she may be reassured by an examination, which shows that the genitalia are normal. The clinician may also recommend a book or website which explains sexual matters.

Specific suggestions

Common-sense advice on sexual techniques may be helpful. Examples of this would be advice about foreplay, spending time with your partner, using sex aids, e.g. vibrators, suggesting different sexual positions, use of vaginal dilators/trainers or the ‘stop-start’ technique.

Sex therapy

Some problems are resistant to simple counselling and require specialist referral. Specialist treatment usually involves an average of about 12 sessions. Sexual therapy consists of behavioural elements and counselling. Both methods allow exploration of the sexual history in a non-threatening and supportive environment. A behavioural approach offers practical solutions to sexual dysfunction supported by the counsellor, e.g. the ‘stop–start’ technique and also includes elements of education about sexual functioning. Counselling aims to explore the reasons behind the sexual dysfunction so the patient can develop a greater understanding of their difficulties in order to solve them.

Conclusion

Sexual problems cause much unhappiness and may present to any clinician. Some can be treated easily with simple advice; others need more prolonged specialist treatment. A few may never respond to treatment. The main aim for a young doctor is to be able to discuss the subject comfortably. This is not easy, as both parties need to overcome their embarrassment. With sexual problems, more than with many aspects of medicine, there are many sensitivities but with experience and some knowledge, any doctor can develop their skills in this area. Sexual medicine is a diverse and interesting area of work and can be very rewarding for both the doctor and the patient.