CHAPTER 60 Sexual dysfunction in urogynaecology

Introduction

Sexuality and its expression contribute to some of the most complex aspects of human behaviour. The expression of sexuality and intimacy remains important throughout the lifespan of a woman, and hence needs to be understood in health as well as in illness. Although sexual problems are highly prevalent, a very small proportion of women consult a physician. In a UK- based survey, 54% of women reported at least one sexual problem lasting for at least 1 month during the previous year, which caused 62% of them to avoid sex. Only 21% with problems had sought help, of which 74% consulted their general practitioner (Mercer et al 2003). A web-based survey of 3807 women in the USA revealed that the most important barriers for women to seek help were embarrassment and feeling that the physician would not be able to provide help. Only 42% of this cohort sought help from their gynaecologist (Berman et al 2003). The high prevalence of sexual dysfunction and reluctance of women to seek help is a reflection on physicians’ attitudes and ability to communicate with female patients about their sexual function.

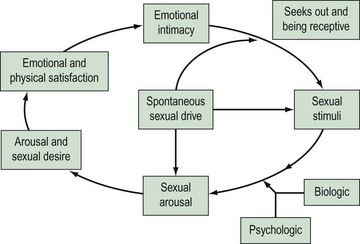

Research into female sexuality has been a neglected area. It was Kinsey’s research in the 1950s on sexual practices in men and women that helped to dispel the myth that women are not interested in sex. However, it has taken a long time to accept that women have a right to sexuality. The advent of new therapies for male sexual dysfunction has led to recent interest in these problems in women. There are a number of reasons why research in the past has focused more on male sexual problems than female. Firstly, it has been difficult to measure appropriate endpoints in clinical trials due to a lack of valid outcome measures. Secondly, the female sexual response is complex, as highlighted by current models (Figure 60.1) compared with the previously described linear models which were based on the relatively uncomplicated male sexual response cycle. The new, non-linear model of female sexual response considers emotional intimacy, sexual stimuli and relationship satisfaction (Basson 2001). This circular model demonstrates that many women initially begin a sexual encounter from a point of sexual neutrality. The decision to be sexual may come from a conscious wish for emotional closeness or as a result of seduction or suggestion from a partner. Women may have numerous reasons for engaging in sexual activity other than sexual drive. Sexual neutrality or being receptive to rather than initiating sexual activity is considered a normal variation of female sexual functioning. In addition, it is frequently the case that subjective and physiological sexual arousal precedes desire.

Definition and Classification

According to the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) (World Health Organization 1992), the definition of sexual dysfunction includes ‘the various ways in which an individual is unable to participate in a sexual relationship he or she would wish’. On the other hand, in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV (DSM-IV) (American Psychiatric Association 1994), female sexual dysfunction (FSD) is defined as ‘disturbances in sexual desire and in the psychophysiological changes that characterise the sexual response cycle and cause marked distress and interpersonal difficulty’. Although both systems recognize the need for a subjective distress criterion, these definitions rely on the linear human response cycle. Furthermore, both systems are based on conceptualization of sexual response as a ‘psychosomatic process’ involving psychological and somatic components. In 1998, the Sexual Function Health Council of the American Foundation devised the first consensus-based definition and classification system for FSD, which was further updated in 2003 (Basson et al 2004) (Box 60.1). FSD is best regarded as a spectrum of disorders with considerable overlap. Understanding this interplay of physical and psychosocial factors in context with illnesses, and medical and/or surgical interventions will help the clinician in managing FSD. Sexual dysfunction may arise because of an illness or disability, a medication or surgical procedure, changes accompanying the ageing process, relationship difficulties, abusive experiences, performance anxiety or any combination of factors such as these (Table 60.1).

Box 60.1 Definition and classification of FSD

Arousal disorder

Table 60.1 Conditions that affect female sexual function and their effects

| Effect(s) | |

|---|---|

| Condition | |

| Oestrogen deficiency e.g. menopause, secondary amenorrhea (binge-eating disorders, rigorous diet), puerperal amenorrhoea (lactational amenorrhoea), contraception with super-light pills, menopause |

Decreased lubrication and arousal |

| Testosterone deficiency e.g. premature iatrogenic menopause |

Decreased desire |

| Diabetes | Decreased lubrication |

| Hormonal disorders e.g. thyroid, pituitary, adrenal |

Decreased lubrication and desire |

| Neurological disorders e.g. Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis |

Decreased lubrication, arousal, desire and difficulty reaching orgasm |

| Genital prolapse | Decreased desire and arousal |

| Urinary incontinence | Decreased desire, arousal and pain |

| Atrophy, vaginitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, endometriosis, vestibulitis, cystitis | Pain and vaginismus |

| Arthritis | Limitation of movement |

| Trauma, sexual assault | Arousal disorder |

| Procedure | |

| Oophorectomy | Decreased desire and lubrication |

| Episiotomy and pelvic floor repairs | Pain |

| Drugs | |

| Antihypertensives e.g. β-blockers, α-blockers, diuretics |

Decreased desire and difficulty reaching orgasm |

| Psychotherapeutic drugs e.g. tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, lithium, benzodiazepines |

Difficulty reaching orgasm |

| Hormones e.g. oral contraceptives, oestrogens, progestins, gonadotrophin-releasing hormone agonists |

Decreased desire |

| Cardiovascular agents e.g. lipid-lowering agents, digoxin |

Decreased desire |

| Chemotherapeutic agents | Vaginal dryness, decreased desire and difficulty reaching orgasm |

Prevalence of Sexual Dysfunction in Women with Urogynaecological Problems

Sexual dysfunction occurs commonly in women attending urogynaecological services. Up to 64% of sexually active women attending a urogynaecology clinic suffer from FSD (Pauls et al 2006). Although it is a very common problem, a recent survey of members of the American Urogynecologic Society (AUGS) showed that only a minority of urogynaecologists screen all patients for FSD. Lack of time, uncertainty about therapeutic options and older age of the patient were cited as potential reasons for failing to address sexual complaints as part of routine history (Pauls et al 2005). A survey of the members of the British Urogynaecological Society (BSUG) using the same questionnaire with a few modifications reflected similar findings. Fifty percent of the BSUG members regularly screened for FSD at clinic visits and 49.5% after surgery, compared with 77% and 76% of AUGS members, respectively. The most important barrier for not enquiring about FSD was lack of time. Seventy-six percent found training for FSD to be unsatisfactory (Roos et al 2009). The similarity in trends between the UK and USA highlights that this may be a more global problem that needs wider exploration. Furthermore, the subject of FSD should be given more importance in the undergraduate and postgraduate curriculum, so that clinicians enquire about this embarrassing problem.

Aetiology of Sexual Dysfunction in Women with Pelvic Floor Dysfunction

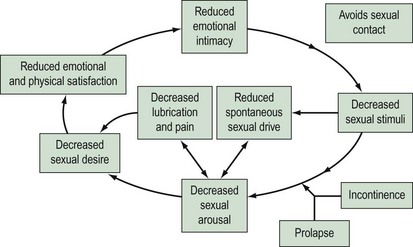

In a survey of 104 patients attending a urogynaecology clinic (Sutherst 1979), 46% admitted that their urinary disorder had an adverse effect on sexual relations. The reasons for reduced frequency of sexual intercourse were superficial or deep dyspareunia (most common), wetness at night and the need for protection of a towel all the time, leakage of urine during coitus, decreased libido, depression or embarrassment, marital discord and the need for separate beds. Women with pelvic organ prolapse may have sexual dysfunction due to mechanical obstruction. However, the reasons probably extend beyond the local effects. It has been shown that women seeking treatment for advanced prolapse have poorer body image and quality-of-life scores compared with women with normal vaginal support (Jelovsek and Barber 2006). Using the female sexual response cycle, one can conceptualize how incontinence and prolapse may affect sexuality. Arousal may be reduced in a woman with coital incontinence or prolapse due to embarrassment. This, in turn, affects orgasm and can also lead to reduced lubrication. Sexual intercourse in this situation will cause the woman to experience pain, which may affect arousal (Figure 60.2).

Relationship between Pelvic Organ Dysfunction and Sexual Function

Evidence from large prospective studies has demonstrated that prolapse and/or incontinence have an adverse effect on sexual function (Rogers et al 2001a, Handa et al 2004, Novi et al 2005). Complaints of stress urinary incontinence, overactive bladder (OAB) and lower urinary tract symptoms have been shown to have a negative impact on all domains of sexual function (Salonia et al 2004, Aslan et al 2005). The most common sexual complaints in women with urinary incontinence are low desire, vaginal dryness and dyspareunia (Handa et al 2004). Amongst the different types of urinary incontinence, OAB has a particularly high association with sexual dysfunction, which could be indicative of an underlying psychosomatic disorder.

Using a validated questionnaire, Novi et al (2005) demonstrated significantly lower measures of sexual function in women with pelvic organ prolapse. Women with prolapse were more likely to have urinary and/or faecal incontinence during sexual activity, more dyspareunia and fewer orgasms. They were also more likely to report negative emotional reactions associated with sex, and higher rates of embarrassment leading to avoidance of sex. Presence of both prolapse and incontinence has a cumulative negative effect on sexual function, with libido, sexual excitement and orgasm being significantly affected (Ozel et al 2006). Increasing severity of prolapse is associated with symptoms related to urinary incontinence, voiding, and defaecatory and sexual dysfunction, which do not necessarily correlate with the location of prolapse and therefore are not compartment specific (Ellerkmann et al 2001).

Effect of Treatment of Pelvic Floor Dysfunction on Sexual Function

Urinary incontinence

Pelvic floor rehabilitation appears to positively influence female sexuality. Zahariou et al (2008) evaluated the effect of a programme of supervised pelvic floor muscle training on sexual function, in a group of women with urodynamically diagnosed stress urinary incontinence, using a validated questionnaire (Female Sexual Function Index, FSFI) 12 months after treatment. All domains of the FSFI improved significantly, with median total FSFI scores increasing from 20.3 to 26.8. The improvement in sexual function could be due to the improvement in strength of the pelvic floor muscles. Pelvic floor contraction plays an important role in female orgasmic response. Furthermore, the strength of the pelvic floor muscles probably affects the anatomical position of the clitoral erectile tissue, with consequences for sexual stimulation. In addition, muscle training improves muscle morphology and neuromuscular function. Although there are extensive data on the effect of various pharmaceutical agents in women with OAB, sexual function has only been evaluated in one study (Sand et al 2006). The Multicentre Assessment of Transdermal Therapy in Overactive Bladder with Oxybutynin study was an open-label, prospective trial of 2878 subjects with OAB, treated with transdermal oxybutynin for 6 months or less. The impact of OAB on sexual function before and after treatment was assessed via item responses from the King’s Health Questionnaire and Beck Depression Inventory-II. At baseline, 23.1% of participants reported that OAB had an impact on their sex life. Coital incontinence in 22.8% of women decreased after treatment to 19.3%. The effects of OAB on subjects’ sex lives improved in 19.1% of cases (worsened in 11.2%), and the effect on relationships with partners improved in 19.6% of cases (worsened in 11.9%). Reduced interest in sex, reported by 52.1% of women at baseline, improved significantly. Considering that sexual dysfunction is highly prevalent in women with OAB, it is surprising that such scarce data are available.

Prior to introduction of the minimally invasive sling suburethral procedures, the Burch colposuspension was regarded as the ‘gold standard’ surgical treatment option for stress urinary incontinence. Considering that the procedure was used for many decades, there are few data on the impact of colposuspension on sexual health. Moran et al (1999) evaluated 55 women with stress urinary incontinence who reported coital incontinence before undergoing colposuspension. Preoperative coital leakage occurred in 65% of women with penetration, 16% with orgasm and 18% with both. After surgery, 81% of the women reported no coital incontinence. Similarly, Baessler and Stanton (2004) showed that 6 months after colposuspension, while stress urinary incontinence improved in 77% of patients, coital incontinence was cured in 70% and improved in almost 7%, which suggests that coital incontinence is likely to be cured when urinary incontinence is successfully treated by Burch colposuspension.

Recent prospective studies of surgery for urinary incontinence using tension-free vaginal tape have found a positive impact on sexual function, primarily because of cure of coital incontinence with the associated emotional benefits of loss of fear and embarrassment due to leakage (Shah et al 2005, Ghezzi et al 2006). Causes of postoperative worsening of sexual function have been attributed to loss of libido, dyspareunia and partner discomfort. Cases of dysfunction due to vaginal erosion of the mesh and de-novo anorgasmia are infrequent. A recent study based on a postal questionnaire survey has shown that the transobturator tape (TOT) procedure can have a positive, but also a negative, outcome on female sexual function (Sentilhes et al 2008). Comparing the TOT procedure with the transvaginal approach, Elzevier et al (2008) found that both procedures had a positive effect on sexual function due to improvement in incontinence. However, pain due to vaginal narrowing was significantly more common in the TOT procedure group.

Prolapse

Sexual activity in women with pessaries in situ is poorly studied. It has been shown that long-term pessary use is acceptable to sexually active women. Using the FSFI questionnaire, Kuhn et al (2009) showed that desire, lubrication and sexual satisfaction improved significantly, and orgasm remained unchanged in women who used pessaries for pelvic organ prolapse and were sexually active.

Anterior repair does not seem to have an effect on sexual function unless it is combined with another procedure. Colombo et al (2000) reviewed 23 women who had an anterior repair for cystocele and stress urinary incontinence 8 years after surgery, and found that 56% had mild-to-severe postoperative dyspareunia. However, all patients in this study also had a posterior repair and perineorrhaphy. Most studies on vaginal surgery in the posterior compartment for rectocele repair have demonstrated improvement in sexual function, with a decrease in dyspareunia when only midline fascial plication or site-specific repair was done (Cundiff et al 1998, Kenton et al 1999, Porter et al 1999, Glavind and Tetsche 2004). However, when the repair involved levator plication, there was a significant increase in dyspareunia following surgery (Kahn and Stanton 1997).

Vaginal vault prolapse surgery is difficult to study as the problem usually involves multiple compartments of the pelvic floor. However, the Colpopexy and Urinary Reduction Efforts trial (Handa et al 2007) provided a unique opportunity to study sexual function in women undergoing sacrocolpopexy with and without colposuspension. Using a validated questionnaire [Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Functioning Questionnaire (PISQ-12)] and telephone interviews 1 year after surgery, the authors found that, after surgery, fewer women reported sexual interference from ‘pelvic or vaginal symptoms’, fear of incontinence, vaginal bulging and pain. More women were sexually active after surgery. The addition of Burch colposuspension did not have an adverse effect on sexual function. Dyspareunia after sacrospinous fixation procedure may be attributable to either vaginal narrowing, pudendal injury, deviation of the vagina or excessive colpectomy during the concomitant repair procedure. The rates of postoperative dyspareunia are reported to be between 8% and 16% (Aslan et al 2005). Iliococcygeal fixation is another technique used to correct vault prolapse. In a matched case–control study comparing sacrospinous with iliococcygeal fixation, Maher et al (2004) found no significant difference in the percentage of women who were sexually active, or who had dyspareunia or buttock pain.

Meshes, both synthetic and biological, on their own or in the form of kits are used increasingly to reinforce vaginal repairs, with the purpose of improving long-term results and preventing recurrences. However, there is very little information about their influence on sexual function. Following repair of large or recurrent anterior and posterior compartment prolapse using an overlay graft (atrium polypropylene), Dwyer and O’Reilly (2004) showed a decrease in dyspareunia over a 24-month period after surgery. In contrast, Milani et al (2005) found a 20% increase in dyspareunia after anterior repair and a 63% increase after posterior repair reinforced by mesh. Neither of these studies assessed other aspects of sexual function. More recently, Novi et al (2007) compared sexual function of women undergoing rectocele repair with porcine dermis graft with site-specific repair of the rectovaginal fascia using a validated questionnaire (PISQ), and found that subjects undergoing porcine dermis graft scored significantly higher on the PISQ 6 months after surgery. There is an urgent need for proper evaluation of meshes in all forms before they are widely used.

Historically, the uterus has been regarded as the regulator and controller of important physiological functions, a sexual organ, a source of energy and vitality, and a maintainer of youth and attractiveness. It is logical to hypothesize that removal of such an organ would lead to sexual problems. However, there is evidence to the contrary. The largest prospective study to date is the Maryland Women’s Health Study (Rhodes et al 1999), which enrolled 1299 women who were interviewed with validated questionnaires before and 6, 12, 18 and 24 months after hysterectomy for benign conditions. They found a significant increase in frequency of sexual activity, a decreased rate of frequent dyspareunia, a decrease in reduced orgasm and a reduction in low libido rates. The distribution of women not experiencing vaginal dryness improved significantly. Overall, this study found substantial improvements in sexual function after hysterectomy. An enduring debate in the late 1980s and the 1990s was whether subtotal hysterectomy might confer advantages over total hysterectomy with regard to sexual, urinary and bowel function, since the former entails minimal neuroanatomical disruption. However, a recent Cochrane review (Lethaby et al 2006) did not demonstrate any difference in pelvic organ dysfunction, quality of life and psychological function in women with and without conservation of the cervix 1 year after surgery, and this effect seems to persist on long-term follow-up (Thakar et al 2008). Roovers et al (2003), in a prospective, observational study over 6 months, found a reduction in sexual problems after vaginal, subtotal or total hysterectomy. However, the prevalence of one or more bothersome sexual problems 6 months after vaginal, subtotal or total hysterectomy was 43%, 41% and 39%, respectively, and new sexual problems developed in over 9% of cases. The authors acknowledged that the size of the study population might have been too small to detect slight differences.

Childbirth and puerperium

In the postpartum period, the combination of a new baby, fatigue, hormonal changes and a healing episiotomy scar may contribute to diminished frequency and enjoyment of sexual intercourse. Recent work on women’s sexual health after childbirth has shown that sexual health problems are common in this period. In a cross-sectional study of 796 primiparous women over a 6-month period after delivery, Barrett et al (2000) found that 32% had resumed intercourse within 6 weeks of birth and 89% had resumed intercourse within 6 months. Sexual health problems, as recalled by the women, increased significantly after childbirth, with 83% experiencing sexual problems in the first 3 months, which declined to 64% at 6 months, although not reaching the prepregnancy levels of 38%. Dyspareunia at 6 months post partum was significantly associated with a previous experience of dyspareunia and current breast feeding. In a further analysis of the same cohort of women, it was found that women who were depressed were less likely than women who were not depressed to have resumed sexual intercourse and to report sexual health problems at 6 months post partum (Morof et al 2003). However, sexual health problems were common after childbirth in both depressed and non-depressed women, and therefore the authors suggested that postnatal sexual morbidity cannot be assumed to be simply a product of depressed mental state. When the mode of delivery was analysed in this cohort of women, in comparison with vaginal delivery, the protective effect of caesarean section on sexual function was limited to the early postnatal period, primarily due to dyspareunia-related symptoms. At 6 months, differences in dyspareunia-related symptoms, sexual-response-related symptoms and postcoital problems between caesarean and vaginal delivery were much reduced or reversed, with none reaching statistical significance (Barrett et al 2005). van Brummen et al (2006) performed a prospective longitudinal study on 377 primiparous women using the Maudsley Marital Questionnaire to evaluate factors which determine sexual activity and sexual relationship 1 year after the first delivery. Not being sexually active in early pregnancy (up to 12 weeks of gestation), older maternal age at delivery and third/fourth degree anal sphincter tear were the main predictors of sexual inactivity and dissatisfaction with sexual relationship at 1 year post partum. Perineal trauma (second, third and fourth) and use of obstetric instrumentation were related to increased frequency and severity of dyspareunia at 6 months post partum.

Evaluation

History

Presentation may be overt, wherein the woman presents with symptoms of lack of desire, orgasm and arousal, and/or pain. Sexual problems are often disguised and may present as unresolved complaints, requests for repeated investigations and multiple consultations, all of which should raise the suspicion of a hidden agenda. Removing the protective coat of the hidden agenda through listening, observing, feeling, interpretation and reflection of all the clues present in the consultation allows for its emergence into the conscious. The hidden agenda of the patient needs to be acknowledged, the reason for the concealment needs to be respected, and the practitioner needs to provide an environment in which it can be expressed without fear. Thus, even taking a brief sexual history during a new patient visit is effective, and indicates to the patient that the discussion of sexual concerns is appropriate and a routine component of the consultation. For screening of sexual problems, simple questions are as effective as lengthy interviews and can be used in clinical settings (Roos et al 2009). Questions regarding the sexual problem should be asked to generate the full picture of current sexual response. The impact of the dysfunction on the patient’s personal well-being and its significance should be quantified. In addition, the role of the partner, and the partner’s sexual response and reaction to sexual problems should be ascertained where possible. As sexual functioning is multifactorial, a thorough medical, surgical, obstetric, gynaecological, psychiatric and social history should also be taken. History of cigarette smoking and alcohol and/or drug intake should be taken. Medications are an important part of the history, as many medications can have an adverse effect on sexual function. However, it should be noted that much of the available information is based on data from male subjects, and it is unknown whether dysfunctions noted in males will also exist in females. A history of sexual assault or trauma is a potential contributor to sexual and pelvic floor dysfunction.

With better understanding of the domains of female sexual function, there has been an increasing use of self-report questionnaires. The advantage of using these questionnaires, apart from the fact that they are valid and reliable measures of sexual function, is that they are easy to administer, relatively inexpensive and unobtrusive, and normative values are available for both clinical and non-clinical populations. Several generic questionnaires are available (e.g. the Brief Index for Sexual Function in Women, the Female Sexual Function Index and the Sexual Distress Scale). Recently, a condition-specific questionnaire has become available to evaluate sexual function in women with incontinence and prolapse — the PISQ. The PISQ was developed and validated in New Mexico in the USA. The PISQ has a long form and a short form. The long form contains 31 items, all with Likert scale responses, which are divided into three domains: behavioural-emotive (comprising 15 questions), physical (ten questions) and partner related (six questions). Higher PISQ scores indicate better sexual function (Rogers et al 2001b). The short form consists of 12 questions and is not divided into the three domains (Rogers et al 2003). The short form of the PISQ is useful in the clinical setting because it reduces the time and burden to the patient, and provides the clinician with objective means of evaluating functional outcomes of either medical or surgical interventions. In the research setting, the short form of the PISQ is useful when quality-of-life analysis is part of the armamentarium used to evaluate outcomes and compare results.

Treatment

Most trials of testosterone replacement therapy have shown statistically significant improvement in sexual function and well-being in women who have undergone oophorectomy. Transdermal testosterone therapy in the form of a patch or gel, which delivers physiological doses, has shown positive impacts on sexual function domains in postmenopausal and surgically menopausal women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder receiving concomitant oestrogen therapy in a recent randomized trial (Kingsberg et al 2007). However, at present, there are no safety and efficacy data for testosterone supplementation in oestrogen-deficient women, with even less support for women who are not oestrogen deficient and who have intact ovaries. Furthermore, the adverse effects of long-term use are largely unknown, with most studies having a follow-up duration of up to 2 years. Risks of androgen therapy include hirsutism, acne, adverse liver function and lipid profile changes, with a potential increase in insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome with long-term use. For surgically menopausal women who present with symptoms of reduced desire, low-dose testosterone can be started along with continuous oestrogen therapy. The response to treatment (both efficacy and side-effects) should be evaluated after 3–6 months. If the problem persists, the patient should be referred to a specialist clinic, or for relationship counselling, psychotherapy or lifestyle advice, as appropriate.

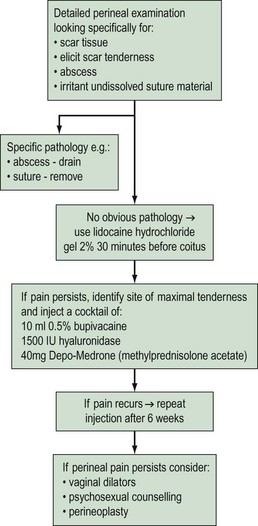

After vaginal delivery, the patient may experience persistent pain over the episiotomy or perineal trauma site. If localized tender scar tissue is identified, women can be advised to have sexual intercourse after application of lidocaine gel/ointment. If pain persists, perineal injections, consisting of a cocktail of 10 ml bupivacaine 0.5%, 1500 iu hyaluronidase and 1 ml Depo-Medrone, is injected into the site of maximal tenderness (Figure 60.3). Occasionally, a woman may present with a perineal skin web in the posterior fourchette or fusion of the labia. These can be divided after infiltrating the area with a local anaesthetic injection. In women who are breast feeding, dyspareunia may be due to vaginal dryness. New mothers could be alerted to this side-effect and given advice on the use of lubricants and oestrogen pessaries or creams if necessary, while being reassured about the benefits of breast feeding. In the absence of local pathology, if a psychosexual problem is suspected, referral to a psychosexual counsellor may be helpful (Thakar and Sultan 2007).

Figure 60.3 Suggested regime for management of perineal pain/dyspareunia.

Adapted from Thakar R and Sultan A (2007) Postpartum problems and the role of a perineal clinic. In: Sultan AH, Thakar R and Fenner D (eds) Perineal and anal sphicncter trauma. Springer-Verlag, London, with permission Springer Science+Business Media.

KEY POINTS

American Psychiatric Association. DSM-IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edn. Washington, DC: APA; 1994.

Aslan G, Koseoglu H, Sadik O, Gimen S, Cihan A, Esen A. Sexual function in women with urinary incontinence. International Journal of Impotence Research. 2005;17:248-251.

Baessler K, Stanton SL. Does Burch colposuspension cure coital incontinence? American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2004;190:1030-1033.

Barrett G, Pendry E, Peacock J, Victor C, Thakar R, Manyonda I. Women’s sexual health after childbirth. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2000;107:186-195.

Barrett G, Peacock J, Victor CR, Manyonda I. Cesarean section and postnatal sexual health. Birth. 2005;32:306-311.

Basson R. Female sexual response: the role of drugs in the management of sexual dysfunction. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2001;98:350-353.

Basson R, Althof S, Davis S, et al. Summary of the recommendations on sexual dysfunctions in women. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2004;1:24-34.

Berman L, Berman J, Felder S, et al. Seeking help for sexual function complaints: what gynecologists need to know about the female patient’s experience. Fertility and Sterility. 2003;79:572-576.

Colombo M, Vitobello D, Proietti F, Milani R. Randomised comparison of Burch colposuspension versus anterior colporrhaphy in women with stress urinary incontinence and anterior vaginal wall prolapse. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2000;107:544-551.

Cundiff GW, Weidner AC, Visco AG, Addison WA, Bump RC. An anatomic and functional assessment of the discrete defect rectocele repair. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1998;179:1451-1456.

Dwyer PL, O’Reilly BA. Transvaginal repair of anterior and posterior compartment prolapse with atrium polypropylene mesh. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2004;111:831-836.

Ellerkmann RM, Cundiff GW, Melick CF, Nihira MA, Leffler K, Bent AE. Correlation of symptoms with location and severity of pelvic organ prolapse. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2001;185:1332-1337.

Elzevier HW, Putter H, Delaere KP, Venema PL, Nijeholt AA, Pelger RC. Female sexual function after surgery for stress urinary incontinence: transobturator suburethral tape vs. tension-free vaginal tape obturator. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2008;5:400-406.

Ghezzi F, Serati M, Cromi A, Uccella S, Triacca P, Bolis P. Impact of tension-free vaginal tape on sexual function: results of a prospective study. International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 2006;17:54-59.

Glavind K, Tetsche MS. Sexual function in women before and after suburethral sling operation for stress urinary incontinence: a retrospective questionnaire study. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2004;83:965-968.

Handa VL, Harvey L, Cundiff GW, Siddique SA, Kjerulff KH. Sexual function among women with urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2004;191:751-756.

Handa VL, Zyczynski HM, Brubaker L, et al. Sexual function before and after sacrocolpopexy for pelvic organ prolapse. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 197, 2007. 629.e1–e6

Jelovsek JE, Barber MD. Women seeking treatment for advanced pelvic organ prolapse have decreased body image and quality of life. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2006;194:1455-1461.

Kahn MA, Stanton SL. Posterior colporrhaphy: its effects on bowel and sexual function. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1997;104:82-86.

Kenton K, Shott S, Brubaker L. Outcome after rectovaginal fascia reattachment for rectocele repair. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1999;181:1360-1363.

Kingsberg S, Shifren J, Wekselman K, Rodenberg C, Koochaki P, DeRogatis L. Evaluation of the clinical relevance of benefits associated with transdermal testosterone treatment in postmenopausal women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2007;4:1001-1008.

Kingsberg S, Janata JW. Female sexual disorders: assessment, diagnosis and treatment. Urologic Clinics of North America. 2007;34:497-506.

Kuhn A, Bapst D, Stadlmayr W, Vits K, Mueller MD. Sexual and organ function in patients with symptomatic prolapse: are pessaries helpful? Fertility and Sterility. 2009;91:1914-1918.

Lethaby A, Ivanova V, Johnson NP 2006 Total versus subtotal hysterectomy for benign gynaecological conditions. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2: CD004993.

Maher CF, Qatawneh AM, Dwyer PL, Carey MP, Cornish A, Schluter PJ. Abdominal sacral colpopexy or vaginal sacrospinous colpopexy for vaginal vault prolapse: a prospective randomized study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2004;190:20-26.

Mercer CH, Fenton KA, Johnson AM, et al. Sexual function problems and help seeking behaviour in Britain: national probability sample survey. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 2003;327:426-427.

Milani R, Salvatore S, Soligo M, Pifarotti P, Meschia M, Cortese M. Functional and anatomical outcome of anterior and posterior vaginal prolapse repair with prolene mesh. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2005;112:107-111.

Moran P, Dwyer PL, Ziccone SP. Burch colposuspension for the treatment of coital urinary leakage secondary to genuine stress incontinence. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1999;19:289-291.

Morof D, Barrett G, Peacock J, Victor CR, Manyonda I. Postnatal depression and sexual health after childbirth. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2003;102:1318-1325.

Novi JM, Jeronis S, Morgan MA, Arya LA. Sexual function in women with pelvic organ prolapse compared to women without pelvic organ prolapse. Journal of Urology. 2005;173:1669-1672.

Novi JM, Bradley CS, Mahmoud NN, Morgan MA, Arya LA. Sexual function in women after rectocele repair with acellular porcine dermis graft vs site-specific rectovaginal fascia repair. International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 2007;18:1163-1169.

Ozel B, White T, Urwitz-Lane R, Minaglia S. The impact of pelvic organ prolapse on sexual function in women with urinary incontinence. International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 2006;17:14-17.

Pauls RN, Kleeman SD, Segal JL, Silva WA, Goldenhar LM, Karram MM. Practice patterns of physician members of the American Urogynecologic Society regarding female sexual dysfunction: results of a national survey. International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 2005;16:460-467.

Pauls RN, Segal JL, Silva WA, Kleeman SD, Karram MM. Sexual function in patients presenting to a urogynecology practice. International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 2006;17:576-580.

Porter WE, Steele A, Walsh P, Kohli N, Karram MM. The anatomic and functional outcomes of defect-specific rectocele repairs. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1999;181:1353-1358.

Rhodes JC, Kjerulff KH, Langenberg PW, Guzinski GM. Hysterectomy and sexual functioning. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282:1934-1941.

Rogers GR, Villarreal A, Kammerer-Doak D, Qualls C. Sexual function in women with and without urinary incontinence and/or pelvic organ prolapse. International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 2001;12:361-365.

Rogers RG, Kammerer-Doak D, Villarreal A, Coates K, Qualls C. A new instrument to measure sexual function in women with urinary incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2001;184:552-558.

Rogers RG, Coates KW, Kammerer-Doak D, Khalsa S, Qualls C. A short form of the Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire (PISQ-12). International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 2003;14:164-168.

Roos AM, Thakar R, Sultan AH, Scheer I. Female sexual dysfunction: are urogynecologists ready for it? International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 2009;20:89-101.

Roovers JP, van der Bom JG, van der Vaart CH, Heintz AP. Hysterectomy and sexual wellbeing: prospective observational study of vaginal hysterectomy, subtotal abdominal hysterectomy, and total abdominal hysterectomy. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 2003;327:774-778.

Salonia A, Zanni G, Nappi RE, et al. Sexual dysfunction is common in women with lower urinary tract symptoms and urinary incontinence: results of a cross-sectional study. European Urology. 2004;45:642-648.

Sand PK, Goldberg RP, Dmochowski RR, McIlwain M, Dahl NV. The impact of the overactive bladder syndrome on sexual function: a preliminary report from the Multicenter Assessment of Transdermal Therapy in Overactive Bladder with Oxybutynin trial. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2006;195:1730-1735.

Sentilhes L, Berthier A, Caremel R, Loisel C, Marpeau L, Grise P. Sexual function after transobturator tape procedure for stress urinary incontinence. Urology. 2008;71:1074-1079.

Shah SM, Bukkapatnam R, Rodriguez LV. Impact of vaginal surgery for stress urinary incontinence on female sexual function: is the use of polypropylene mesh detrimental? Urology. 2005;65:270-274.

Sutherst JR. Sexual dysfunctional and urinary incontinence. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1979;86:387-388.

Thakar R, Sultan A. Postpartum problems and the role of a perineal clinic. In: Sultan AH, Thakar R, Fenner D, editors. Perineal and Anal Sphincter Trauma. London: Springer-Verlag; 2007:65-79.

Thakar R, Ayers S, Srivastava R, Manyonda I. Removing the cervix at hysterectomy: an unnecessary intervention? Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2008;112:1262-1269.

van Brummen HJ, Bruinse HW, van de Pol G, Heintz AP, van der Vaart CH. Which factors determine the sexual function 1 year after childbirth? BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2006;113:914-918.

World Health Organization. ICD-10: International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. Geneva: WHO; 1992.

Zahariou AG, Karamouti MV, Papaioannou PD. Pelvic floor muscle training improves sexual function of women with stress urinary incontinence. International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 2008;19:401-406.