Chapter 57 Severe pre-existing disease in pregnancy

The two main sources of information about the spectrum of pre-existing conditions that result in severe morbidity in pregnancy are national or local registries/databases and published case series of admissions to intensive care, high-dependency units or obstetric units. Information about mortality comes from registries of maternal death such as the Confidential Enquiries into Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH; formerly Reports on Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths) in the UK, or from individual case series. Taken together, the most important pre-existing conditions likely to lead to intensive care unit (ICU) admission and/or death overall are cardiac disease, respiratory disease, neurological disease, psychaiatric disease (including drug addiction) and haematological, connective tissue and metabolic disease.

CARDIAC DISEASE

There are more maternal deaths in the UK from cardiac disease than from pre-eclampsia and haemorrhage combined.1 Over the last 20–40 years, there has been a shift away from acquired cardiac disease (mainly rheumatic heart disease) towards congenital heart disease as modern techniques of cardiac surgery in early life enable female babies with previously fatal conditions to reach maturity. More recently, there has been an increase in prevalence of ischaemic heart disease resulting from increased obesity, maternal age and smoking. Mortality varies from less than 1% in uncomplicated conditions to over 40% in Eisenmenger’s syndrome, even with modern methods of medical management.2

PHYSIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The physiological changes of pregnancy are discussed in Chapter 56. The changes most relevant to cardiac disease are:

GENERAL ANTEPARTUM AND PERIPARTUM MANAGEMENT

An obstetric and anaesthetic plan should be prepared and the intensivists informed of the anticipated delivery date. Antithromboembolic prophylaxis should be considered since cardiac patients are more at risk, even without prolonged bedrest. Low-molecular-weight heparins are now standard for prophylaxis, although both heparin and warfarin have been used for patients with prosthetic heart valves, the main decision being between the better safety profile of heparin for the fetus but with greater risk of thrombosis in the mother, and the more effective anticoagulation achieved with warfarin but with greater risk of fetal complications.3 The requirements for heparin increase in pregnancy, so greater doses than normal are usually required.

The principles of peripartum management have moved over the last few years towards vaginal delivery unless caesarean section is indicated for obstetric indications. Elective caesarean section has been advocated in the past as a matter of course, traditionally under general anaesthesia, but the stresses and complications of surgery are now generally felt to exceed those of a well-controlled vaginal delivery. Low-dose epidural regimens using weak solutions of local anaesthetic (e.g. 0.1% bupivacaine or less) with opioids such as fentanyl have been found to be effective and cardiostable.4 Combined spinal epidural analgesia using similar low concentrations are also suitable, and continuous spinal analgesia has also been described. In patients with marked exercise intolerance, outlet forceps or ventouse delivery is usually recommended to limit pushing and the duration of the second stage. If caesarean section is required, both regional and general anaesthesia have their advocates,5,6 but either is acceptable so long as due care is taken.

Oxytocin analogue (Syntocinon) has marked cardiovascular effects7,8 that, although tolerable in normal patients, may cause a calamitous drop in systemic vascular resistance with hypotension, tachycardia and worsening of shunt in susceptible patients. If Syntocinon is required it should be diluted and given very slowly (e.g. 5 units infused over 10–20 minutes). Withholding of oxytocics altogether may be a problem as such patients may be especially sensitive to acute blood loss. In patients with fixed cardiac outputs and no pulmonary hypertension, ergometrine may be preferable. At caesarean section, mechanical compression of the uterus with a ‘brace’ suture may be used to reduce or avoid the need for oxytocics.9 Exacerbation of right-to-left shunt is manifested by worsening hypoxaemia, which may be improved by vasoconstrictors such as phenylephrine – the chronotropic and inotropic effects of ephedrine are often undesirable in patients with cardiac disease.

Monitoring ranges from simple non-invasive methods to peripheral arterial, central venous and pulmonary arterial cannulation, depending on the severity of the underlying disease.10 Arterial cannulation is usually straightforward but central venous cannulation is often difficult because of the increased maternal body weight and fluid retention, and the inability to lie flat, let alone head-down. The antecubital fossa should be considered as a route for cannulation first. Scrupulous attention must be paid to avoiding intravascular air in patients with right-to-left shunts, because of the risk of systemic embolism.

Common peripartum complications are summarised in Table 57.1.

Table 57.1 Common peripartum problems in patients with pre-existing cardiac disease

POSTPARTUM COMPLICATIONS

RESPIRATORY DISEASE

The most common respiratory causes of morbidity and mortality in pregnancy are pneumonia, asthma and cystic fibrosis; thus the latter two conditions are the most common pre-existing respiratory diseases that cause mothers to present to ICUs.1,12–14

Asthma is very common but rarely causes serious morbidity in its own right, although there is a higher risk of maternal and neonatal morbidity.12

Cystic fibrosis is relatively rare but is more likely to be associated with poor outcomes.13,14 Studies suggest that pregnancy itself does not increase mortality in women with mild cystic fibrosis and that the risk factors are the same as in non-pregnant patients (pre-pregnancy forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) < 50–60% of predicted; colonisation with Burkholderia cepacia; and pancreatic insufficiency). Overall mortality has been reported as 5% within 2 years of pregnancy, 10–20% within 5 years of pregnancy and 20–21% within 10 years. Psychological support is an important consideration. The decision to have a child, with the risk of passing on the cystic fibrosis gene and the adverse effect that pregnancy might have on the mother, is one that imposes a great deal of stress on the mother, her partner and their relatives.

NEUROLOGICAL DISEASE

GENERAL MANAGEMENT

Until recently, regional analgesia and anaesthesia was traditionally avoided in most neurological disease, for fear of exacerbating the condition, or being blamed for an exacerbation should it occur. Nowadays, most authorities actively encourage regional analgesia for labour since it reduces the physiological demand and thus the risk of respiratory insufficiency or excess fatigue. Similarly, regional anaesthesia for caesarean section avoids the problems of excessive postoperative sedation and how or whether to use neuromuscular-blocking drugs, including suxamethonium. Initial fears about an increased relapse rate of multiple sclerosis following regional anaesthesia have fortunately not been borne out by large prospective series.15

If there is raised intracranial pressure, the use of regional techniques is more controversial. On the one hand, labour and vaginal delivery without effective analgesia can result in marked increases in intracranial pressure; on the other, accidental dural puncture can be disastrous. Even if successfully placed, rapid epidural injection may be associated with increases in intracranial pressure.16 This risk still exists with epidural analgesic techniques continued into the postoperative period.

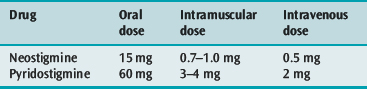

Myasthenia gravis poses a particular problem because of the need for regular medication throughout labour and after delivery. Gastric emptying may be decreased during labour, especially if systemic opioids are given, although this effect can also occur (albeit to a lesser extent) with boluses of epidural opioids. It is therefore important to consider alternative routes of administering the mother’s drug therapy if opioids are given in this way. A useful guide is offered in Table 57.2. Epidural analgesia can be very helpful in limiting maternal fatigue during and after labour. The mother needs watching carefully for signs of increasing weakness up to 7–10 days postpartum.

PSYCHIATRIC DISEASE (INCLUDING DRUG ADDICTION)

Psychiatric disease features consistently in surveys of maternal morbidity and mortality, for example through parasuicide or suicide, violence or the complications of drug addiction. In recent CEMACH reports, suicide and psychiatric disease are relatively common causes of death overall.1 Psychiatric patients may be more vulnerable to becoming pregnant, and pregnant women more vulnerable to suffering from psychiatric disease either during or after pregnancy.

Abuse of drugs poses similar problems to those in the non-pregnant population, with the additional effect of fetal addiction and retarded growth. In particular, cocaine is commonly abused in parts of the developed world and has been implicated in causing placental abruption and maternal convulsions, hypertension and tachycardia, with increased morbidity and mortality for both mother and fetus.17 Unplanned operative intervention for delivery is more likely, which may contribute to an increased requirement for intensive care. The combination of substance abuse and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection poses a particular challenge in the obstetric patient.

1 Lewis G, editor. The Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH). Saving mothers? lives: reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer 2003–2005. The seventh report on confidential enquiries into maternal deaths in the united kingdom. CEMACH, London, 2007.

2 Uebing A, Steer PJ, Yentis SM, et al. Pregnancy and congenital heart disease. Br Med J. 2006;332:401-406.

3 Bates SM, Greer IA, Hirsh J, et al. Use of antithrombotic agents during pregnancy: the Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy. Chest. 2004;126(Suppl. 3):627S-644S.

4 Suntharalingam G, Dob D, Yentis SM. Obstetric epidural analgesia in aortic stenosis: a low-dose technique for labour and instrumental delivery. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2001;10:129-134.

5 Brighouse D. Anaesthesia for caesarean section in patients with aortic stenosis: the case for regional anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 1998;53:107-109.

6 Whitfield A, Holdcroft A. Anaesthesia for caesarean section in patients with aortic stenosis: the case for general anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 1998;53:109-112.

7 Weis FR, Markello R, Mo B, et al. Cardiovascular effects of oxytocin. Obstet Gynecol. 1975;46:211-214.

8 Pinder AJ, Dresner M Calow C, et al. Haemodynamic changes caused by oxytocin during caesarean section under spinal anaesthesia. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2002;11:156-159.

9 Hayman RG, Arulkumaran S, Steer PJ. Uterine compression sutures: surgical management of postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:502-506.

10 Fujitani S, Baldisseri M. Hemodynamic assessment in a pregnant and peripartum patient. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(10):S354-s361.

11 Yentis SM, Steer P, Plaat F. Eisenmenger’s syndrome in pregnancy: maternal and fetal mortality in the 1990s. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105:921-922.

12 Kwon HL, Belanger K, Bracken MB. Effect of pregnancy and stage of pregnancy on asthma severity: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:1201-1210.

13 McMullen AH, Pasta DJ, Frederick PD, et al. Impact of pregnancy on women with cystic fibrosis. Chest. 2006;129:706-711.

14 Gillet D, de Braekeleer M, Bellis G, et al. Cystic fibrosis and pregnancy. Report from French data (1980–1999). Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002;109:912-918.

15 Confavreux C, Hutchinson M, Hours MM, et al. Rate of pregnancy-related relapse in multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:285-291.

16 Hilt H, Gramm HJ, Link J. Changes in intracranial pressure associated with extradural anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 1986;58:676-680.

17 Ludlow JP, Evans SF, Hulse G. Obstetric and perinatal outcomes in pregnancies associated with illicit substance abuse. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;44:302-306.

mismatch with a large effective physiological dead space. The key to management is control and clearance of the underlying infection but this can be very difficult.

mismatch with a large effective physiological dead space. The key to management is control and clearance of the underlying infection but this can be very difficult.