CHAPTER 75 Seronegative Inflammatory Arthritis

INTRODUCTION

Seronegative inflammatory arthritis refers to a group of conditions in which clinical evidence of noninfectious, active inflammation (Box 75-1) is noted in the joints, but serum autoantibodies, such as rheumatoid factor (RF) or anticyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies (anti-CCP), are absent. RF is widely used as a diagnostic marker for rheumatoid arthritis (RA), despite its presence in other inflammatory and infectious conditions. RF can also be detected in some healthy individuals. In recent years, anti-CCP antibodies have been shown to be as sensitive as RF in the diagnosis of RA, but with greater specificity.9 Seventy-five to eighty percent of patients with RA are seropositive for these autoantibodies.9 Therefore, the term seronegative inflammatory arthritis excludes RA.

For the purposes of this discussion, the seronegative inflammatory arthridites will include spondyloarthropathies, crystalline arthropathies, and adult Still’s disease (Box 75-2).

SPONDYLOARTHROPATHIES

Spondyloarthropathies (SpA) are a group of inflam-matory disorders that includes ankylosing spondylitis (AS), psoriatic arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, and reactive arthritis, also known as Reiter’s syndrome. They share an increased prevalence of the human leukocyte antigen class I molecule B-27. Classically, the spondyloarthropathies manifest as an inflammatory arthritis of the spine and sacroiliac joints, but an asymmetric peripheral arthritis can occur as well. A key clinical feature distinguishing SpA from RA is the presence of enthesitis. Enthesitis refers to inflammation that is located at the sites of ligamentous insertion into bone, such as the Achilles tendon or plantar fascia. Table 75-1 illustrates several clinical differences between the SpA and RA. The relative frequency of elbow involvement in the SpA is shown in Table 75-2.

TABLE 75-1 Clinical Differences Between Spondyloarthropathies and Rheumatoid Arthritis

| Feature | Spondyloarthropathies | Rheumatoid Arthritis |

|---|---|---|

| Pattern of peripheral joint involvement | Asymmetric | Symmetric |

| Sacroiliac joint involvement | Very common | Rare |

| Lumbar spine involvement | Very common | Rare |

| Rheumatoid factor and CCP antibody | Rare | Very common |

| Predominant inflammation | Enthesitis | Synovitis |

| HLA association | HLA B-27 | HLA DR |

| Extra-articular features | Mucositis, uveitis, IBD, psoriasis, dysuria | Nodules, vasculitis, lung disease, syndrome |

CCP, cyclic citrullinated peptide; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; IBD, irritable bowel disease.

TABLE 75-2 Elbow Involvement in Spondyloarthropathies

| Spondyloarthropathy | Frequency of Elbow Involvement | Radiographic Appearance |

|---|---|---|

| Ankylosing spondylitis | 12%7 | Joint space narrowing, demineralization and periostitis |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 25%5 | Erosive disease common |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 35%6 | Nonerosive, nondeforming |

| Reactive arthritis | Uncommon | Similar to psoriatic arthritis |

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the cornerstone of medical management of spondyloarthropathies. They reduce inflammatory features, and reduce joint pain and stiffness. The most common adverse events with the use of NSAIDs are gastrointestinal, and range from dyspepsia in 10% to 20% of patients to serious bleeding or gastroduodenal perforation in 7.3 to 13/1000 patients per year.10

CRYSTALLINE ARTHROPATHIES

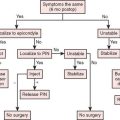

Crystalline arthropathies are a group of inflammatory arthritides associated with crystal deposition in the synovial space. The primary conditions included in this group are gout and pseudogout. Patients frequently present with an acute painful monoarthritis, which often is indistinguishable from septic arthritis. Timely aspiration to rule out infection and SF analysis to confirm the diagnosis is essential. The relative frequency of elbow involvement in crystalline arthropathies is shown in Table 75-3.

| Crystalline Arthropathy | Frequency of Elbow Involvement | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Gout | 17–33%1, 4 | Often accompanied by olecranon bursitis or tophi |

| Pseudogout | 16%8 | Usually post-traumatic |

Gout is a common condition associated with the deposition of monosodium urate (MSU) crystals in the SF and synovial tissue. MSU crystals are by-products of an aberrant uric acid metabolism. Risk factors for gout include hypertension, renal insufficiency, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, ethanol intake, lead exposure, and the use of diuretics, particularly thiazide diuretics.2 The diagnosis is confirmed by finding the presence of the MSU crystals in SF under polarizing microscopy. Frequently, but not always, serum uric acid levels may be elevated during an acute gout attack.

MSU crystals are long, needle-shaped, and demonstrate strong negative birefringence under compensated polarized light. That is, they appear bright yellow under the polarizing microscope. During an attack of gout, MSU crystals are often found within white blood cells from synovial fluid. If a tophus is aspirated and examined, the crystals are often found outside the cells as well.

Patients with chronic gout may develop tophi. Tophi are deposits of MSU crystals in the subcutaneous tissues, which are often very painful. The olecranon bursa is a frequent location for tophi in patients with chronic gout. Figure 75-1 depicts such an example. A radiograph of a patient with tophaceous gout is seen in Figure 75-2.

ADULT STILL’S DISEASE

Adult Still’s disease (ASD) is a rare form of seronegative inflammatory arthritis. It shares many clinical features with systemic-onset juvenile RA, which accounts for about 10% of the cases of juvenile RA. Hallmarks of ASD are its extra-articular features including high fever, rash, adenopathy and serositis, and the absence of autoantibodies. ASD can potentially cause a destructive arthritis. The frequency of elbow involvement in chronic ASD ranges from 4% to 44%.3,11

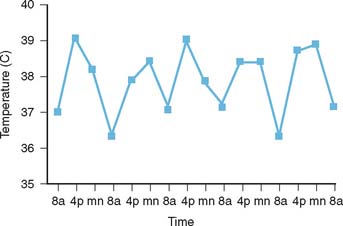

The diagnosis of ASD is frequently made in the clinical setting of a fever of unknown origin. Clinical and exclusion criteria are described in Table 75-4.12 The characteristic salmon-colored evanescent maculopapular rash of ASD is frequently observed at the time of the fever spikes and tends to be located on the trunk. The fevers are more prominent during the afternoon and evening hours as depicted in Figure 75-3.

TABLE 75-4 Criteria for Diagnosing Adult Still’s Disease (ASD)

| Major Criteria | Minor Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Arthralgia >2 weeks | Sore throat | Infection |

| Temperature > 39°C intermittent, ≤1 week | Lymphadenopathy and/or splenomegaly | Malignancy Rheumatic diseases |

| Typical rash | Abnormal liver function tests | |

| WBCs >10,000/L (> 80% granulocytes) | Negative ANA and RF |

*Diagnosis of ASD requires five criteria, at least two major.

ANA, antinuclear antibody text; RF, rheumatoid factor; WBC, white blood cells.

Data from Yamaguchi, M., Ohta, A., Tsunematsu, T., Kasukawa, R., Mizushima, Y., Kashiwagi, H., Kashiwazaki, S., Tanimoto, K., Matsumoto, Y., Ota, T., and Akizuki, M.: Preliminary criteria for classification of adult Still’s disease. J. Rheumatol. 19:424, 1992.

1 Barthelemy C.R., Nakayama D.A., Carrera G.F., Lightfoot R.W.Jr., Wortmann R.L. Gouty arthritis: a prospective radiographic evaluation of sixty patients. Skeletal Radiol. 1984;11:1.

2 Choi H. Epidemiology of crystal arthropathy. Rheum. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2006;32:255.

3 Efthimiou P., Paik P.K., Bielory L. Diagnosis and management of adult onset Still’s disease. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2006;65:564.

4 Hadler N.M., Franck W.A., Bress N.M., Robinson D.R. Acute polyarticular gout. Am. J. Med. 1974;56:715.

5 McHugh N.J., Balachrishnan C., Jones S.M. Progression of peripheral joint disease in psoriatic arthritis: a 5-yr prospective study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2003;42:778.

6 Orchard T.R., Wordsworth B.P., Jewell D.P. Peripheral arthropathies in inflammatory bowel disease: their articular distribution and natural history. Gut. 1998;42:387.

7 Resnick D. Patterns of peripheral joint disease in ankylosing spondylitis. Radiology. 1974;110:523.

8 Resnick D., Niwayama G., Goergen T.G., Utsinger P.D., Shapiro R.F., Haselwood D.H., Wiesner K.B. Clinical, radiographic and pathologic abnormalities in calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate deposition disease (CPPD): pseudogout. Radiology. 1977;122:1.

9 van Boekel M.A., Vossenaar E.R., van den Hoogen F.H., van Venrooij W.J. Autoantibody systems in rheumatoid arthritis: specificity, sensitivity and diagnostic value. Arthritis Res. 2002;4:87.

10 Wolfe M.M., Lichtenstein D.R., Singh G. Gastrointestinal toxicity of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999;340:1888.

11 Wouters J.M., van de Putte L.B. Adult-onset Still’s disease; clinical and laboratory features, treatment and progress of 45 cases. Q. J. Med. 1986;61:1055.

12 Yamaguchi M., Ohta A., Tsunematsu T., Kasukawa R., Mizushima Y., Kashiwagi H., Kashiwazaki S., Tanimoto K., Matsumoto Y., Ota T., Akizuki M. Preliminary criteria for classification of adult Still’s disease. J. Rheumatol. 1992;19:424.