CHAPTER 23 Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy and Axillary Dissection

INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY

I. Breast Cancer

A. Patients with invasive breast cancer who can safely undergo surgery benefit from lymph node staging. This is generally achieved through sentinel lymph node biopsy. Exceptions include patients with axillary lymphadenopathy suspicious for metastatic disease and patients who have had previous breast or chest wall irradiation, which may disrupt the lymphatics and preclude accurate lymphatic mapping. Such patients should forgo sentinel lymph node biopsy in favor of axillary dissection. Elderly patients or those with significant comorbidities, with favorable stage I tumors, also may forgo sentinel lymph node biopsy.

B. Although patients with in situ breast cancers should not, theoretically, have nodal metastases, invasive foci in the area of the in situ disease is present in 10% to 30% of patients. A number of indications for sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with ductal carcinoma of the breast (DCIS) have, therefore, emerged. Sentinel lymph node biopsy is indicated in patients with multicentric or broad areas of high-grade DCIS, as well as in those undergoing total mastectomy (which precludes subsequent nodal staging without axillary dissection).

II. Melanoma is the eighth most common cancer in the United Stated and the most common cause of skin cancer–related deaths. Tumor thickness is the dominant prognostic factor and is correlated with the risk of regional metastasis. Generally, sentinel lymph node biopsy is offered to patients with melanomas exceeding 1 mm in thickness. Completion lymphadenopathy is performed if the sentinel node is found to contain metastatic disease. Patients with “intermediate-thickness” melanomas (1–4 mm) are at relatively higher risk of having nodal metastases compared with patients with thinner lesions, but they are at lower risk, compared with patients with thicker lesions, of having distant metastases. Notably, the therapeutic utility of sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with such lesions was recently evaluated in the Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial. This trial compared wide local excision and sentinel lymph node biopsy with wide local excision alone for the treatment of intermediate-thickness melanomas and demonstrated a survival advantage for patients randomized to the former treatment group who had nodal micrometastases.

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION

I. Breast Cancer

A. The evaluation of a suspected breast cancer typically includes breast examination, mammography, and breast biopsy. Additional diagnostic modalities increasingly used in the evaluation of breast lesions include ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging. The goals of this evaluation are to: (1) establish a tissue diagnosis, (2) clinically stage patients, and (3) identify candidates for breast-conserving therapy versus patients who require mastectomy.

B. An assessment for regional metastases should begin with a physical examination of the bilateral axillary and supraclavicular fossae. Adenopathy suggestive of metastatic disease may be further evaluated with fine-needle aspiration; malignant cells seen on cytologic evaluation or a high degree of suspicion for nodal metastases should prompt axillary dissection rather than sentinel lymph node biopsy.

II. Melanoma

A. The evaluation of a suspected melanoma begins with a biopsy to both diagnose and microstage the lesion if proven to be a melanoma. Excisional biopsy (i.e., removal of the lesion with grossly negative margins) is the optimal technique for smaller lesions. A punch biopsy directed at the clinically thickest area is sufficient for larger lesions. Shave biopsies may preclude accurate assessment of tumor thickness and should be avoided. After biopsy, tumor thickness is characterized on the basis of anatomic level of invasion (Clark level) and, most importantly, by thickness in millimeters (Breslow thickness). Subsequent wide excision margins reflect the risk of recurrence and are determined by tumor thickness. Tumors less than 1 mm thick are best excised with 1-cm margins whereas lesions thicker than 1 mm may require initial margins of 2 cm.

B. As in breast cancer, an assessment for regional metastases should begin with a physical examination of the potential draining lymph node basins. In the absence of clinically evident nodal metastases, sentinel lymph node biopsy should be performed in conjunction with wide local excision of the primary tumor.

C. In patients with lesions thicker than 1 mm, a baseline chest radiograph and liver function tests as well as a lactate dehydrogenase level should be obtained. Patients with thicker lesions (≥4 mm) are at relatively high risk for distant metastases. A more rigorous evaluation for metastases, including computed tomography (CT) scans or positron emission tomography and CT scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis, should be obtained before surgery.

APPLIED ANATOMY AND COMPONENTS OF THE PROCEDURE

Preoperative Considerations

I. Prophylactic antibiotics are not generally administered before sentinel lymph node biopsy. Most surgeons give antibiotics before axillary dissection. The chosen antibiotic should have activity against skin flora (i.e., gram-positive organisms) and should be administered within 1 hour before skin incision.

Patient Positioning and Preparation

I. The patient is placed in the supine position. The axilla is exposed by extending the arm at a 90-degree angle.

II. The sterile preparation should include the axilla and upper arm. When performed in conjunction with a mastectomy, the preparation should also include the ipsilateral breast, extending several inches past the midline, above the clavicle and below the inframammary fold. Laterally, the preparation should extend to the posterior axillary line.

Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy

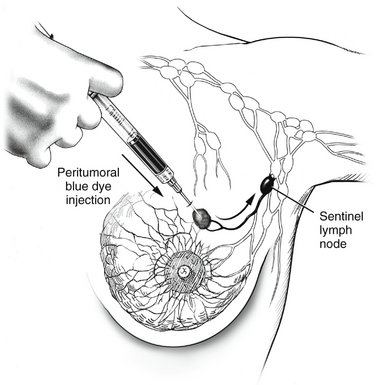

I. Radioisotope-labeled tracer (technetium-99m sulfur colloid) is injected 1 or more hours before sentinel lymph node biopsy. In patients with melanomas of the trunk or head and neck, particularly if near the midline, where lymphatic drainage may be ambiguous, lymphoscintigraphy should be performed in the nuclear medicine suite after the injection of tracer. This technique, which tracks the tracer with a scintiscanner as it travels from the injection site to the sentinel node, can be helpful in accurately identifying the laterality or bilaterality of the sentinel nodes (e.g., right vs. left axilla or bilateral axillae). In the operating room, minutes before making the incision, the surgeon injects vital blue dye 10 minutes or more before making the incision (Fig. 23-2). In the patient with melanoma, the tracer and dye are injected intradermally so that they may enter the dermal lymphatics draining the site. In patients with breast cancer, injection may be performed using a number of different approaches, with largely equivalent results; the most common sites for injection include the peritumoral breast parenchyma and the subareolar breast parenchyma.

II. A gamma probe is calibrated and placed on the surgical field in a sterile sheath to allow for subsequent localization of the radioisotope-labeled tracer.

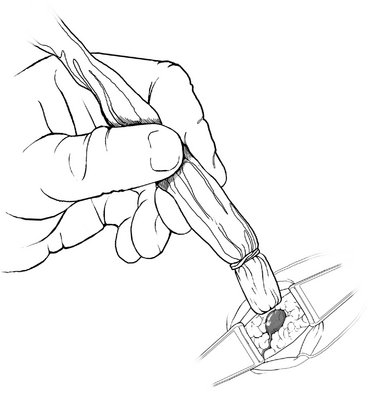

V. Blue-stained lymphatics are identified. The gamma probe may be used to help direct the surgeon toward the area of maximal uptake (Fig. 23-3).

VI. Blue channels are traced proximally and distally to identify blue nodes with high radioisotope counts (as detected by the gamma probe).

Axillary Dissection

I. A curvilinear incision is made just below the hair-bearing area of the axilla, extending laterally to the posterior axillary line and medially no further than the lateral edge of the pectoralis major muscle.

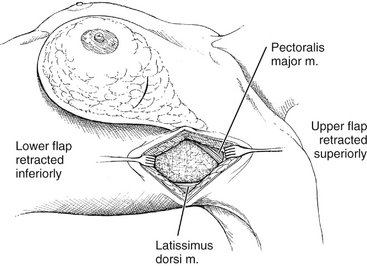

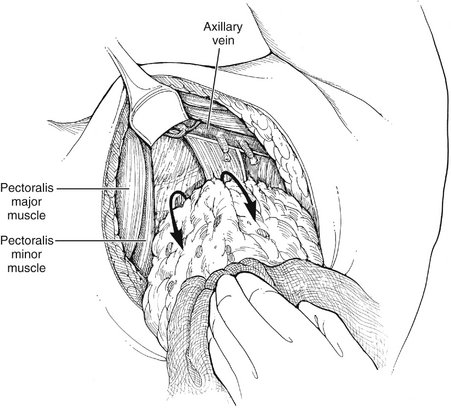

II. Flaps are developed beneath the subcutaneous layer, extending medially to the edge of the pectoralis major muscle, superiorly to its tendinous insertion, inferiorly to the level of the sixth rib, and posteriorly to the edge of the latissimus dorsi (Fig. 23-4).

III. Medial retraction of the pectoralis major allows for the identification of the lateral edge of the pectoralis minor muscle. The medial pectoral nerve is identified lateral to the pectoralis minor muscle and preserved.

IV. The clavipectoral fascia, contiguous with the pectoralis minor fascia, is opened parallel to the lateral edge of the muscle, exposing the lymphadipose contents of the axilla.

V. Superior and medial retraction of the pectoralis muscle and inferior traction on the lymphadipose tissue allow for exposure of the axillary vein.

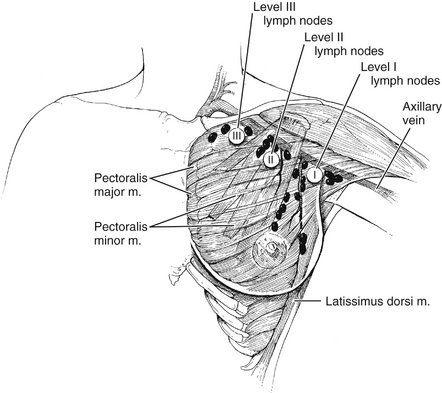

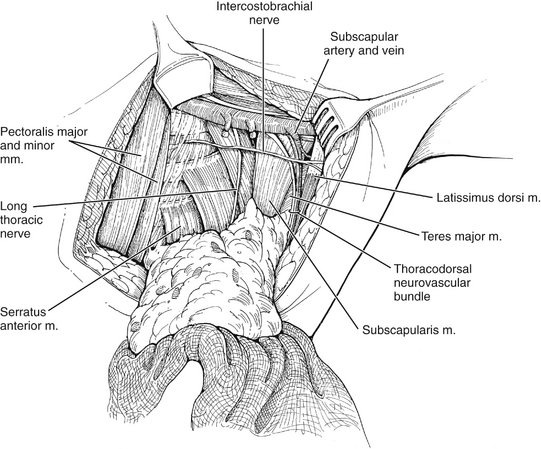

VI. Lymphatic dissection proceeds along the axillary vein, beginning medially beneath the pectoralis minor muscle (level II nodes) and proceeding laterally (Fig. 23-5).

VII. As the dissection proceeds, the inferior axillary contents are dissected off the serratus anterior fascia.

VIII. The intercostobrachial nerve is identified as it exits the second intercostal space and is preserved, if possible.

IX. As the dissection is carried toward the junction of the serratus anterior and subscapularis muscles, lateral intercostal perforating vessels are divided and ligated.

X. The long thoracic nerve is identified as it courses superficial and lateral to the serratus anterior muscle, and is preserved.

XI. The thoracodorsal nerve and vessels are identified as they course over the subscapularis muscle and are preserved (Fig. 23-6). The remaining lateral axillary contents are dissected with the specimen, which is transected at the border of the latissimus dorsi muscle.

COMPLICATIONS

I. Seroma formation is anticipated after axillary dissection. Accumulation may be minimized through maintenance of closed-suction drainage for the first week after surgery. Seroma formation after the drain is removed may be managed by aspiration.

II. Lymphedema, manifested by swelling or heaviness of the ipsilateral arm, is not uncommon after axillary dissection, with an incidence of 5% to 25%. In most cases, lymphedema is subtle; obvious or disabling enlargement is uncommon. Radiation therapy (for breast cancer) and obesity are contributory factors. Arm elevation, weight loss, and the use of elastic pressure-graded sleeves may be helpful.

III. Lymphangiosarcoma is a rare, but devastating, complication associated with chronic lymphedema, and is heralded by vascular-appearing nodules in the edematous extremity (Stewart-Treves syndrome). The mean interval between surgery and the diagnosis of lymphangiosarcoma is 10 years. Therapy may include wide local excision or even amputation. Unfortunately, the prognosis is very poor, with a median survival of 2 years.

IV. Nerve injury may result from axillary dissection. Nerves at risk include the intercostobrachial, long thoracic, thoracodorsal, and medial pectoral. Division of the intercostobrachial nerve results in numbness or paresthesias of the upper medial nerve and axilla. These symptoms often resolve over months because of the rich sensory innervation of the area. Division of the long thoracic nerve results in a winged scapula from paralysis of the serratus anterior muscle, whereas division of the thoracodorsal nerve results in limitation of backward motion of the extended arm from denervation of the latissimus dorsi muscle. Division of the medial pectoral nerve may result in atrophy of the lateral pectoralis major muscle.

Lange JR, Balch CM. Cutaneous melanoma. In Cameron JL, editor: Current Surgical Therapy, 8th ed, Philadelphia: Mosby, 2004.

Morton DL, Thompson JF. Sentinel-node biopsy or nodal observation in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1944.

Roses DF, Guiliano AE. Surgery for breast cancer. In Roses DF, editor: Breast Cancer, 2nd ed, Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone, 2005.