CHAPTER 19 Adrenalectomy

Case Study

She undergoes laboratory testing, which reveals a serum potassium level of 3.1 mEq/L, a serum renin level of 1.31 ng/mL/hr (normal range, 0.15–3.39 ng/mL/hr), and a serum aldosterone level of 82 ng/dL (normal range, 1–16 ng/dL). A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen shows a 2-cm left adrenal mass and a normal-appearing right adrenal gland (Fig. 19-1).

BACKGROUND

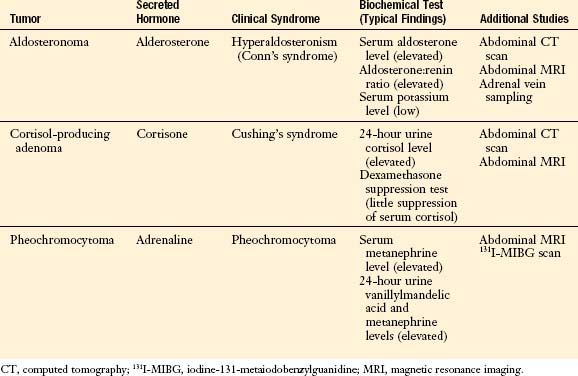

Tumors arising within the adrenal gland are broadly categorized as either functioning or nonfunctioning. The former secrete one of a number of hormones (Table 19-1). The indications for adrenalectomy, the subject of this chapter, include the treatment of functioning adrenal tumors, suspected primary adrenal malignancies, and in select cases, isolated metastases from extra-adrenal malignancies.

INDICATIONS FOR ADRENALECTOMY

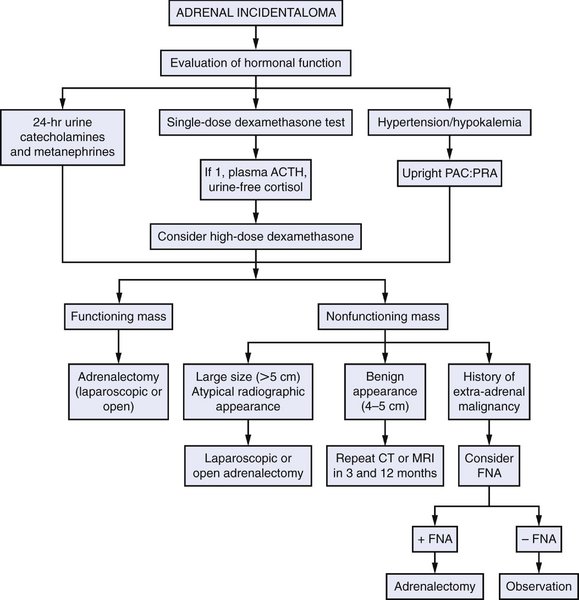

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION

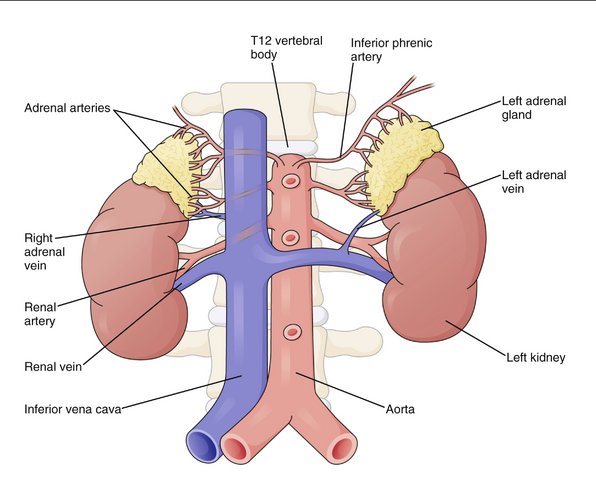

COMPONENTS OF THE PROCEDURE AND APPLIED ANATOMY

Preoperative Considerations

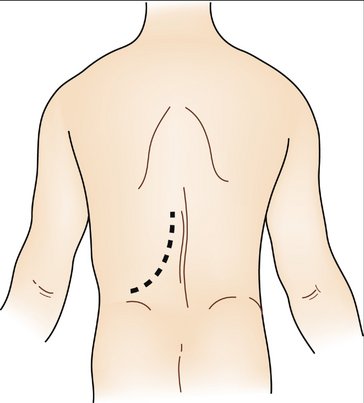

Patient Positioning and Preparation

Port Placement

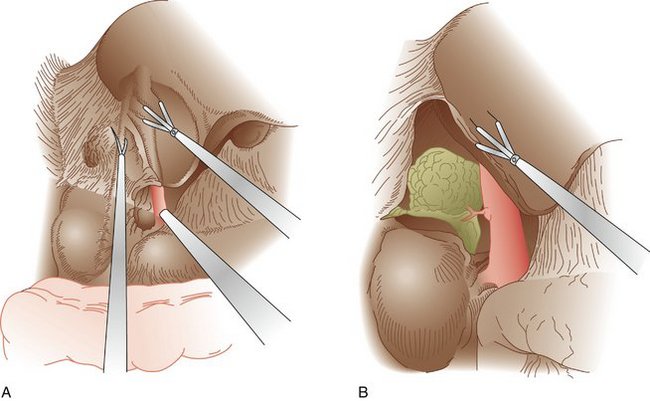

Right Adrenalectomy

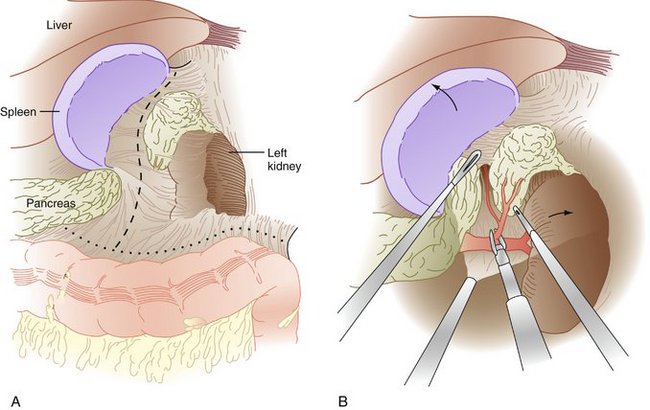

Left Adrenalectomy

Other Operative Approaches

Additional Operative Considerations

NORMAL POSTOPERATIVE COURSE

Additional Postoperative Considerations

Complications

Brunt LM. Minimal access adrenal surgery. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:351-361.

Cobb WS, Kercher KW, Sing RF, Heniford BT. Laparoscopic adrenalectomy for malignancy. Am J Surg. 2005;189:405-411.

Gumbs AA, Gagner M. Laparoscopic adrenalectomy. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;20:483-499.

Mitchell IC, Nwariaku FE. Adrenal masses in the cancer patient: surveillance or excision. Oncologist. 2007;12:168-174.