Sentinel Laboratory Response to Bioterrorism

1. Define and give examples of a biocrime.

2. Define and give examples of select agents.

3. Site two laws that govern the possession of select agents.

4. List the government agencies that must be notified, by registration, before a laboratory may possess a select agent.

5. State the components of a biosecurity plan.

6. Summarize the standard operating procedures required for laboratories that maintain select agents.

7. Diagram and give a brief description of the Laboratory Response Network.

8. Outline the steps microbiology laboratories must follow if a select agent is isolated from a clinical specimen.

9. Explain the requirements for operation as a sentinel laboratory.

10. Name the government agencies responsible for the investigation and management of a bioterrorism event.

Government Laws and Regulations

The bombings at the World Trade Center in 1993 and the federal building in Oklahoma City in 1995 led Congress to pass the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996. Section 511 (d) restricts the possession and use of materials capable of producing catastrophic damage in the hands of terrorists by requiring their registration. A companion law, the Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism (USA PATRIOT) Act of 2001 prohibits any person to knowingly possess any biologic agent, toxin, or delivery system of a type or in a quantity that, under the circumstances, is not reasonably justified by prophylactic, protective, bona fide research, or other peaceful purpose. Later, the Public Health Security and Bioterrorism Preparedness and Response Act of 2002 required institutions to notify the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) or the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) of the possession of specific pathogens or toxins called select agents. Therefore, clinical laboratories possessing any select agents must register with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), a branch of the DHHS. Violation of any of these statutes carries criminal penalties. The pathogens and toxins classified as select agents are listed in Box 80-1. List is updated as needed.

Biosecurity

Each clinical laboratory should have a bioterrorism response plan. The plan should include policies and procedures to be enacted when a suspicious isolate cannot be ruled out as a biothreat agent. If a laboratory has any questions about isolating, identifying, or submitting an organism that may be an agent of bioterrorism, laboratory personnel should call the state public health laboratory. The select agent must be either sent to a public health laboratory or destroyed within 7 days of identification. If the agent is autoclaved, its destruction must be documented using Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS)/CDC Form 4, which can be downloaded at www.selectagents.gov/CDForm.html.

Laboratory Response Network

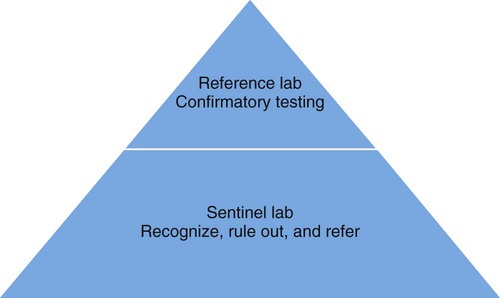

Laboratory testing and communication between clinical and public health laboratories is critical when responding to a bioterrorism event. To address this issue, the CDC, in partnership with the Association of Public Health Laboratories and the Federal Bureau of Investigation, established the Laboratory Response Network (LRN). The LRN is a three-tier system. Sentinel (formerly level A) laboratories receive patient samples, rule out pathogens, and transfer suspicious specimens to reference laboratories. References laboratories possess the required reagents and technology to perform confirmatory testing on pathogens. These labs may be local public health, military, international, veterinary, agriculture, food, or water testing laboratories. Confirmed bioterrorism agents are sent to a national laboratory. National laboratories, such as those at the CDC, U.S. Army Medical Research Institute for Infectious Diseases, or the Naval Medical Research Center, are responsible for the definitive characterization of agents (Figure 80-1).

Role of the Sentinel Laboratory

• A laboratory having an active microbial surveillance and monitoring program

• Vigilant technologists looking for a disease that (1) does not occur naturally in a particular geographic region (e.g., plague in New York City); (2) is transmitted by an aerosol route of infection; and (3) is a single case of disease caused by an unusual agent (e.g., Burkholderia mallei)

• Good communication with infection control practitioners, infectious disease physicians, and local or regional public health laboratories

Sentinel laboratories must have a class II biologic safety cabinet, copies of level A protocols containing the algorithms for ruling out suspicious microorganisms (Table 80-1), and participate in an applicable proficiency testing program such as the College of American Pathologist’s Laboratory Preparedness Survey. Because sentinel laboratories rule out and refer microorganisms, proper knowledge of appropriate packaging and shipping is critical (see Chapter 4); all specimens must be classified as infectious. Sentinel laboratories should never accept nonhuman specimens such as those from animals or the environment. Such specimens should be submitted directly to the nearest reference laboratory.

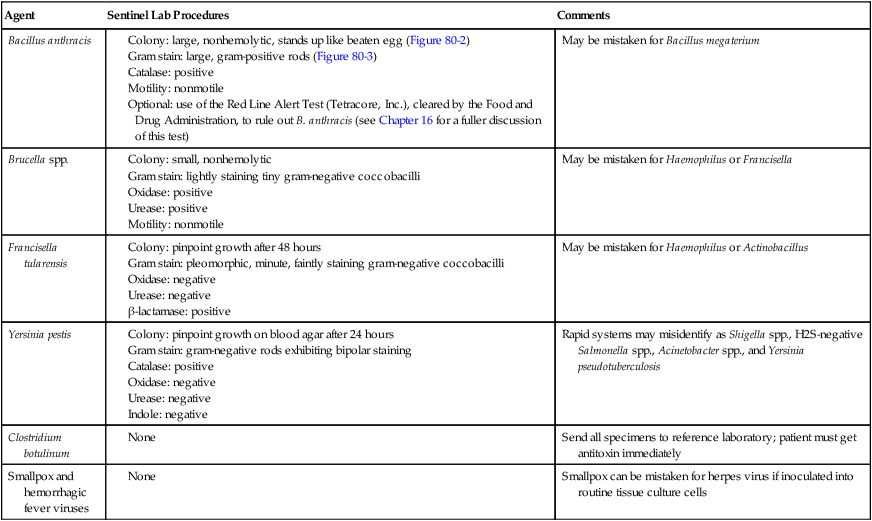

TABLE 80-1

Algorithm for Sentinel Laboratories for Likely Bioterrorism Agents*

| Agent | Sentinel Lab Procedures | Comments |

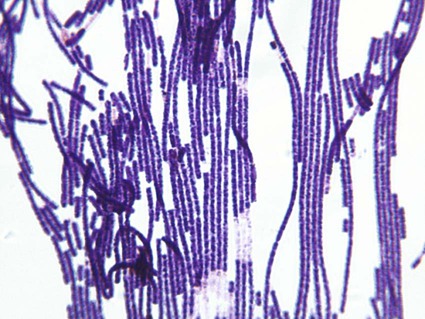

| Bacillus anthracis |

Colony: large, nonhemolytic, stands up like beaten egg (Figure 80-2) Gram stain: large, gram-positive rods (Figure 80-3) Optional: use of the Red Line Alert Test (Tetracore, Inc.), cleared by the Food and Drug Administration, to rule out B. anthracis (see Chapter 16 for a fuller discussion of this test) |

May be mistaken for Bacillus megaterium |

| Brucella spp. |

*See individual chapters for a more detailed discussion of each organism.

A sentinel laboratory’s key responsibility is to be familiar with likely agents involved in a biocrime; it must have standard operating procedures (SOPs) to accomplish this task. To standardize the process nationwide, the American Society for Microbiology (ASM) has compiled a series of guidelines. These guidelines are listed in Box 80-2 and may be accessed on the ASM website at www.asm.org/index.php/what-s-new-in-public-policy/sentinel-level-clinical-microbiology-laboratory-guidelines.html. Algorithms for the identification of likely bioterrorism agents are provided in Table 80-1.