CHAPTER 57 Semiconstrained Elbow Replacement: Results in Traumatic Conditions

INTRODUCTION

Damage or loss of the articular cartilage of the elbow joint may occur in comminuted intra-articular fractures. Late osteoarthrosis may develop as a result of traumatic cartilaginous damage or joint incongruence of insufficiently reduced intra-articular fractures or subluxed unstable elbows.

The treatment of choice for most displaced intra-articular fractures of the elbow joint is open reduction and internal fixation.28,32,33 In a review of nine studies of osteosynthesis of distal humerus fractures, fair to poor outcomes were reported in 25%, with a high complication rate.28 Secondary procedures were required in 70% of the cases. In the elderly, open reduction and internal fixation can be particularly difficult because of marked osteoporosis and extensive comminution.28,33,68

In elderly patients, the use of hip arthroplasty for fracture of the femoral neck is well accepted.13 Similarly, hinged semiconstrained total elbow replacement got wide acceptance in the recent years as an excellent alternative to open reduction and internal fixation of comminuted fractures of the distal humerus, and might be considered the treatment of first choice in properly selected cases of extensively comminuted fractures in patients older than 65 years of age.*

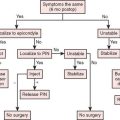

Post-traumatic osteoarthrosis, however, differs from acute traumatic conditions in several aspects and poses greater treatment difficulties. This chronic painful condition is usually characterized by stiffness, joint and bone deformity with extensive soft tissue contractures, bone loss, and instability. Typically, one or more previous procedures have resulted in a poor soft tissue envelope, infection, and nerve injury.59

Few options exist for salvage of severe post-traumatic osteoarthrosis. Arthrodesis reliably relieves pain41 but results in great functional impairment,54 and hence, is rarely considered a viable option (see Chapter 70).15,46 Interposition arthroplasty may be considered for a young patient, particularly one who has stiffness. Restoration of motion and relief of pain can be achieved with a reasonable (62% to 70%) but unpredictable rate of success.8,19,37,44,65 However, this procedure has an even higher rate of complications than that associated with semiconstrained total elbow replacement (see Chapter 69).8,50 Interposition arthroplasty also is not considered suitable for patients who perform strenuous physical labor.37 Varying results have been reported for allograft replacement of the entire elbow joint.1,11,14,66 Concern about the complication rate, instability, continued degenerative changes and fragmentation, and neurotrophic changes of the allograft explain why this procedure has not found wide acceptance (see Chapter 67).

INDICATIONS

ACUTE TRAUMA

The treatment of choice for acute fractures of the distal humerus is open reduction and internal fixation, if possible.32,33 The indication for semiconstrained total joint replacement for acute fractures of the distal humerus is mainly limited to patients older than about 65 years of age with an extensively comminuted fracture that is not amenable to an adequate and stable osteosynthesis. The usual findings are as follows: (1) a large number of small fragments, (2) poor mechanical quality of severe osteoporotic bone, (3) significant loss of joint fragments in open injuries, and (4) pre-existing joint damage in patients with rheumatoid arthritis or other inflammatory joint diseases.

TRAUMATIC ARTHROSIS

For post-traumatic osteoarthrosis, total joint replacement using the semiconstrained Coonrad-Morrey prosthesis is, in our hands, the treatment of choice in selected cases. These cases include advanced destruction of the ulnohumeral joint with marked narrowing or loss of the joint space. This pathology is believed to preclude other reliable treatment modalities, such as débridement or ulnohumeral arthroplasty, and only for those patients who are older than 60 years of age. For patients younger than 60 years, total elbow replacement should be performed only with reservation, if no other suitable alternatives of operative treatments are available or for those in whom other reconstructive procedures have failed, such as interposition arthroplasty.5 Furthermore, replacement is reserved only for those patients who do not perform strenuous physical activities.

Our experience with the semiconstrained Coonrad-Morrey prosthesis for the treatment of post-traumatic osteoarthritis revealed mechanical complications of the implant in 17% of the cases, most occurring in patients younger than 60 years of age.59 Hence, membership in this group, participation in heavy physical work, and anticipated noncompliance are considered relative contraindications for this procedure. For young patients with a severe post-traumatic osteoarthrosis, interposition arthroplasty may be considered the treatment of first choice, rather than total joint replacement (see Chapter 69). In cases of failed interposition arthroplasty, total joint replacement is the treatment of choice for most patients.

FURTHER CONSIDERATIONS

AGE, OCCUPATION, AND PHYSICAL ACTIVITY

Because the total elbow prosthesis is a mechanical device, it is subjected to wear, particularly of the polyethylene bushings.67 In our series, those with post-traumatic osteoarthrosis who were younger than 60 years of age had a higher rate of complications (35% versus 17%) and, accordingly, a lower proportion of satisfactory results (78% compared to 89%).59 The prosthesis does not tolerate the stress of heavy physical work; thus, after a total elbow replacement, we always advise the patient to avoid single-event lifting of objects that weigh more than 5 kg as well as the repetitive lifting of any object that weighs more than 1 kg. We discourage the playing of golf and other impact sports.

INSTABILITY

Acute or post-traumatic instability is not a contraindication to elbow replacement that involves the use of the semiconstrained Coonrad-Morrey implant53,59; in fact, the condition is well managed with this device.56 Owing to its hinge design, this implant yields immediate and durable stability. In contrast to certain other semiconstrained implants,25 the Coonrad-Morrey device provides valgus-varus and axial stability without the tendency for the components to disassemble. This topic is discussed further in Chapter 53.

BONE LOSS

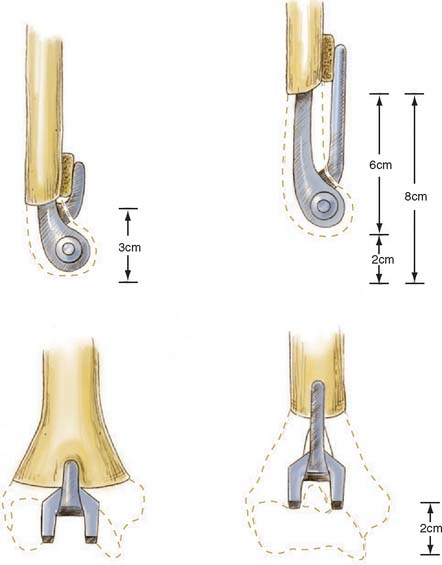

Significant bone stock deficiency was present in 13 of the 41 patients in our series with post-traumatic osteoarthrosis.59 Only the humeral diaphysis is required to obtain secure fixation of the Coonrad-Morrey prosthesis. Rotational and anteroposterior stability is maintained by the anterior flange and bone graft (Fig. 57-1). Thus, this implant does not require the condyles for mechanical support. In acute injuries, the fractured condyles are completely removed, as in the treatment of nonunions (see Chapter 59).48 In post-traumatic osteoarthrosis, loss of the condyles does not require their re-construction. This enormously facilitates total elbow replacement and constitutes a great advantage over those total elbow prostheses that need the condyles for stability.24,25,64

A loss of the distal humerus up to 6 to 8 cm can easily be managed by the noncustom Coonrad-Morrey device.35 The length of the condyles is approximately 3 cm. If the bone loss extends into the supracondylar area and into the shaft of the humerus, the Coonrad-Morrey humeral component with the long anterior flange can be used compensating for another 3 cm of bone loss. In addition, the humeral component can be cemented up to 2 cm more proximally into the shaft. This results, however, in shortening of the humerus with potential weakening of the muscles crossing the elbow joint.30 However, in chronic situations, this might not be appreciated by patients because of muscle contracture or preoperative weakness from pain. In a retrospective analysis, Hildebrand and coauthors29 measured the extensor muscle strength in 16 patients after Coonrad-Morrey elbow replacement for traumatic or posttraumatic conditions. Although the patients had approximately a three times weaker extension strength of the replaced compared with the contralateral elbows, the patient satisfaction with the result of elbow arthroplasty was very high, and triceps weakness did not seem to be clinically appreciated by the patients. Similarly, McKee and coauthors42 measured the muscle strength of the elbow, forearm, wrist, and hand muscles in 16 patients with Coonrad-Morrey total elbow replacement that had resection of both condyles and compared the values with 16 cases that had intact condyles. They found no significant differences between the two groups with regard to the various strength measurements and with regard to the Mayo Elbow Performance score.

Traumatic loss of the proximal ulna is a difficult problem and requires reconstruction with allograft or autograft from the iliac crest to restore the site of insertion of the extensor mechanisms (see Chapter 66).

DEFORMITY

Deformity is a feature often encountered in post-traumatic osteoarthrosis expressed as angular abnormalities of more than 30 degrees or translational problems (Fig. 57-2; see also Fig. 57-9).59,61 Long-standing deformity results in asymmetrical soft tissue contractures. Unlinked resurfacing total elbow prostheses usually cannot correct this type of deformity, and instability is common. Although hinged semiconstrained prostheses have the major advantage of being able to correct deformity, this correction may be at the expense of persistent or increased asymmetrical loads imparted by the distorted soft tissues, causing an increased wear of the prosthesis. Overall, in our experience, a marked preoperative deformity of the elbows was associated with a significantly higher rate of complications (P = .02).59

TECHNIQUE: TRAUMATIC CONDITIONS

The operative technique for the implantation of the semiconstrained Coonrad-Morrey prosthesis is described in Chapter 53.47 However, some features are unique to this type of prosthesis and should be emphasized. An open type II or III compound fracture should first be irrigated and débrided to avoid wound infection. Total elbow replacement is then performed in a second stage. A type I wound may be treated in a single stage after careful and thorough débridement.

A posterior midline incision is used, including posterior scars from previous procedures. Alternatively, prior medial and lateral incisions can be used for exposure. The ulnar nerve is always identified and transposed anteriorly in a subcutaneous pocket, if the procedure has not already been performed. If condyles are present, the recommended operative technique includes a triceps-sparing approach, which is accomplished by the release and lateral reflection of the triceps from the olecranon in continuity with the ulnar periosteum and the fascia of the forearm, along with the anconeus, as described by Bryan and Morrey.7 Alternatively, particularly in acute fractures involving the condyles, the triceps insertion is left intact.35 Overall, triceps strength measurements are not different between the elbows in which the triceps was left on the olecranon and those in which the triceps was reflected and then reattached to the olecranon.29

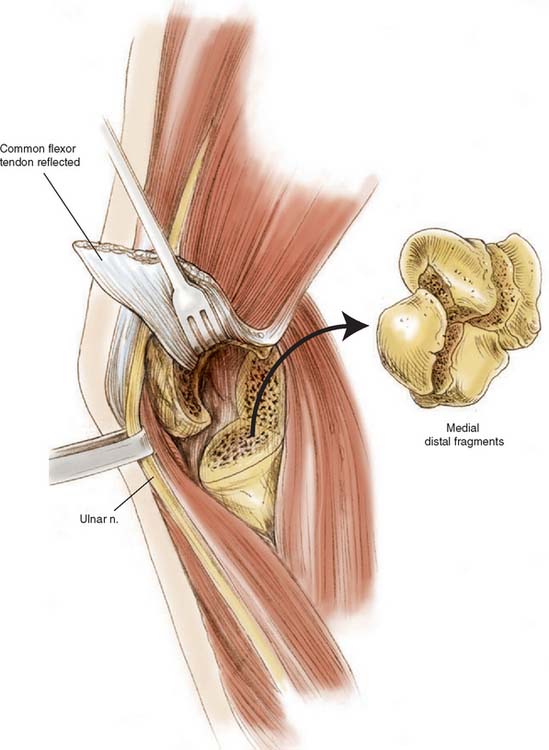

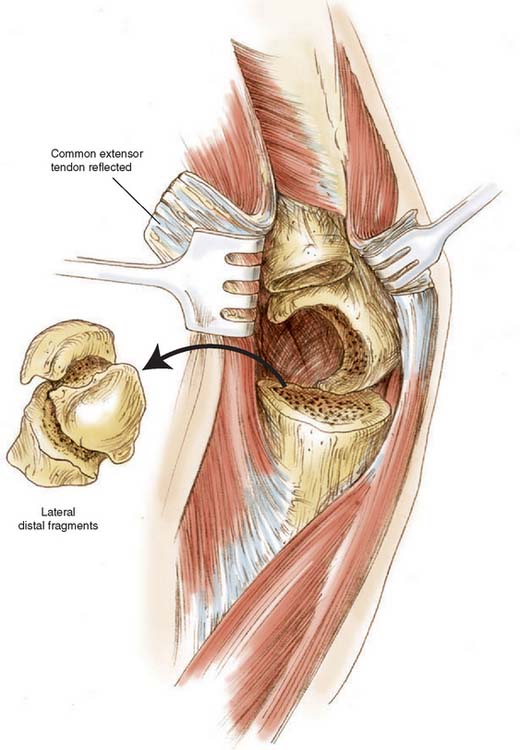

If contracted soft tissue persists, the humeral component is inserted more proximally after removal of additional humeral bone. All soft tissues are released from the humeral fragments, which are then excised (Fig. 57-3). Cultures are taken if there has been prior surgery. The collateral ligaments are detached from the epicondyles, which allows complete exposure of the elbow joint. The repair of the collateral ligaments is not necessary.

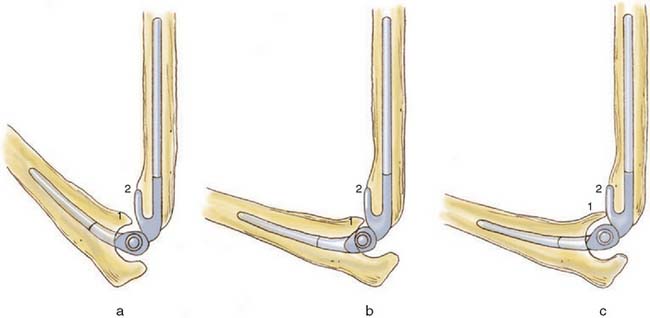

Usually, resection of the tip of the coronoid process is necessary to avoid impingement with the anterior flange, which would cause considerable distraction forces on the ulnar component.61 Too deep insertion of the ulnar component is another potential cause of anterior impingement (Fig. 57-4).

An intramedullary injecting system is used for optimal insertion of cement to which 1 g of vancomycin has been added for every 40 g of cement.16 An important element is the placement of a bone graft between the anterior flange and the distal part of the humerus to resist, after ingrowth, posterior displacement and rotational stresses on the humeral component. Ingrowth of this bone graft is consistently observed, confirming its role in absorbing mechanical loads.59

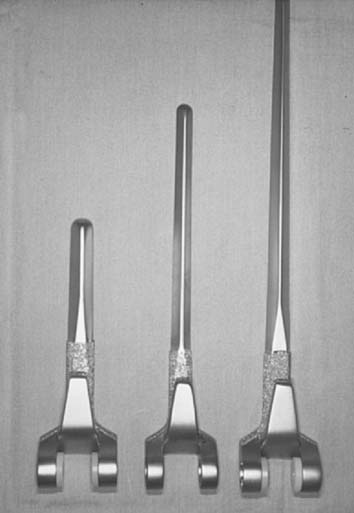

The device offers three lengths of humeral component: 10, 15, and 20 cm in standard, small, and extra small sizes with a regular or long anterior flange (Fig. 57-5). In cases of post-traumatic osteoarthrosis, we normally use the 15-cm stem. If the patient needs or may need a shoulder replacement, the shorter 10-cm stem for the elbow prosthesis may be a more appropriate choice to avoid a conflict of the elbow and shoulder implants within the humeral diaphysis. Variable lengths and diameters of the ulna are also available.

RESULTS

REVIEW OF EARLY LITERATURE

The results of total elbow replacements with highly constrained designs in the 1970s were disappointing because of high rates of loosening.12,22,51 Although less loosening was reported after the introduction of semiconstrained and unconstrained replacement devices,10,15,24,46,55 those reports dealt almost exclusively with the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. In the 1980s and early 1990s, there was very little information regarding total elbow replacement with an unconstrained or a semiconstrained device for the treatment of post-traumatic osteoarthrosis.* Most of what has been reported showed unfavorable results.36,38,40,63 In 1980, Inglis and Pellicci,31 reported little improvement in nine patients who had been managed with a semiconstrained Pritchard-Walker triaxial implant. Lowe and colleagues40 reported a satisfactory result in only one of seven trauma patients who had an unconstrained device. In 1984, Soni and Cavendish63 reported a good or excellent result for only three of eight patients who had an unconstrained implant. Other than our own experience, Figgie and associates17 reported the first positive experience with a semiconstrained (triaxial) prosthesis with custom-designed stems for the treatment of post-traumatic conditions. Results in eight of the nine patients reported were satisfactory.17 However, different designs with variable stems, as well as fixation with or without cement, were used. In 1994, Kraay and coworkers38 reported the experience with a linked semiconstrained implant. Of 113 patients, only 18 had been managed for post-traumatic osteoarthrosis, nonunion, or fracture. The results in these patients were disappointing, with a 5-year rate of survival of the implants of only 53%. There were five loose humeral components and two infections among the 18 patients. In 1996, Gschwend and colleagues25 reported their experience in 26 patients with post-traumatic osteoarthrosis of the elbow treated with total joint replacement using the semiconstrained GSB III implant. The mean follow-up was 4.3 years (maximum 14 years). Pain relief was obtained in 82% of cases. The mean arc of flexion was 34 to 126 degrees. However, the revision rate was 31% owing to aseptic loosening in two, disassembly in four, and ectopic bone formation in two elbows. Another series of 14 patients treated with the GSB III prosthesis was presented in the year of 2000.60 Four of them had been treated for post-traumatic arthrosis. The mean follow-up of the 14 patients was 6 years (range, 2 to 9 years). Overall, 29% of the cases required revision due to gross aseptic loosening.

SEMICONSTRAINED TOTAL ELBOW REPLACEMENT

ACUTE FRACTURES

The first comprehensive series of total elbow replacement for acute fractures was introduced in 1997 by Cobb and Morrey.9 In 2004, an update of the Mayo experience, and in 2005 particular features of the surgical technique was presented by Kamineni and Morrey.34,35,52 It was a series of 49 semiconstrained Coonrad-Morrey total elbow replacements treated at the Mayo Clinic between 1982 and 2001. Forty-three out of these 49 elbows had a minimum follow-up of 2 years (average 7 years; range, 2 to 15). The main inclusion criteria for treatment with total elbow replacement were a fracture that was not amenable to open reduction and internal fixation because of extensive articular comminution (23 elbows), a fracture that had been treated elsewhere with osteosynthesis and had subsequent failure within one month (3 elbows), articular surface destruction by rheumatoid arthritis (17 elbows), pre-existing arthritis (3 elbows), or substantial osteopenia (3 elbows) (Fig. 57-6). The mean age of the patients at the time of injury was 69 years (34 to 92 years). On the basis of the Mayo elbow performance score, 40 patients had a good or excellent result (93%), and three had a fair outcome. Pain relief was reliably obtained, with 35 patients having no pain and 8 patients having mild pain. The mean arc of flexion-extension was 24 to 131 degrees. Severe osteoporosis was common, but it did not appear to influence the functional result.

Later reports confirmed the positive Mayo experience.18,20,21,57,58 Three different series of elderly patients treated with the Coonrad-Morrey total elbow prosthesis for acute distal humeral fractures were presented between 2000 and 2002 from various centers.20,21,57 All patients of these three series uniformly showed excellent or good results according to the Mayo Elbow Performance score, no or only mild pain, and a good range of motion. There were no patients with moderate or severe pain. And after follow-ups of 1 to 5.5 years, there were no loose implants observed.

In 2000, Ray and coauthors57 presented a series of seven elderly patients treated with the Coonrad-Morrey total elbow prosthesis for distal humeral fractures and followed for 2 to 4 years. According to the Mayo Elbow Performance Score, five patients had an excellent and two had a good result. Six patients had no pain, and one patient had mild pain. There were no cases of loosening in this series.

In 2001, Gambirasio and coauthors20 presented a series of 10 patients with complex fractures of the distal humerus treated with the Coonrad-Morrey prosthesis. After a mean follow-up of 1.5 years (range, 1 to 3) all had a satisfactory outcome. Eight had no pain, and two had mild pain. The mean arc of flexion was from 24 to 126 degrees.

In 2002, Garcia and coauthors21 presented a similar series of 16 patients with fractures of the distal humerus treated with the Coonrad-Morrey total elbow prosthesis. After a mean follow-up of 3 years (range, 1 to 5.5), 11 patients had no pain, and four had mild pain. According to the Mayo Elbow Performance score, all patients had an excellent (11 patients) or a good (five patients) outcome. There were no cases of loosening in this series.

In a retrospective analysis presented in 2003, Frankle and coauthors18 compared open reduction and internal fixation with primary total elbow replacement using the Coonrad-Morrey device in the treatment of intra-articular distal humerus fractures in women older than 65 years of age. After a mean follow-up of 5 years (range, 2 to 6.5), all 12 patients treated with joint replacement had an excellent (11 patients) or a good outcome (1 patient) according to the Mayo Elbow Performance score, whereas only eight patients (67%) of the internal fixation group had an excellent or good outcome; one had a fair result, and three had a poor result.

Other semiconstrained total elbow prostheses have been introduced in the last few years for the treatment of acute distal humerus fractures. Similarly to the Coonrad-Morrey prosthesis, these devices have an anterior flange to resist posterior and rotational stresses on the humeral component.27 Long-term data, however, are not yet available with these recently introduced devices.

POST-TRAUMATIC ARTHROSIS

An in-depth review of the Mayo experience was presented in 1997 by Schneeberger and associates. This is by far the most comprehensive series in the literature consisting of 41 consecutive patients treated from 1981 to 1993 with semiconstrained Coonrad-Morrey elbow replacement and followed an average of almost 6 years.59 The average age of the patients was 57 years (range, 32 to 82 years). The indication for joint replacement was pain for 36 patients; reduced, painful range of motion for two patients, and dysfunction with a flail elbow for three patients. The average time from the original fracture to the joint replacement was 16 years (range, 3 months to 64 years).

This is a very difficult group of patients to manage. All but two patients (95) had had previous surgery (Fig. 57-7), the average being 2.3 procedures (range, 0 to 7 procedures). Significant bone stock deficiency with loss of at least one condyle was present in 13 patients, and 14 patients had a significant joint or bone deformity (Fig. 57-8). Ten of 41 elbow joints were preoperatively subluxed, and seven were dislocated. Additional complications from prior surgery included mild to moderate ulnar neuropathy in six patients and radial nerve palsy due to a complete traumatic laceration in one patient.

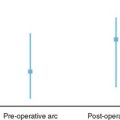

At the latest follow-up, objectively 40% were rated excellent and 43% were considered good, for an overall rate of 83% satisfactory objective outcome. Subjectively, 95% of the patients with a functioning implant expressed satisfaction with the operation. Although the rate of pain relief (76%) was considered to be rather high, it was not as high as that reported after the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (97%).23 At follow-up, the mean arc of flexion-extension was 27 to 131 degrees, and the mean arc of pronation-supination was 66 to 64 degrees. An average of 4.8 of the five activities of daily living could be performed by the patients, and strength improvement averaged approximately 30%.3,49

A review of the patients that had been treated at Balgrist, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery of the University of Zurich, showed a similar series of 16 patients treated between 1996 and 2001 for post-traumatic arthrosis with the Coonrad-Morrey prosthesis.62 At latest follow-up, or at revision due to loosening (one case) or infection (one case), 12 patients (75%) had an excellent or a good outcome according to the Mayo Elbow Performance Score. If at the latest follow-up also the two patients after revision of their failed implants were included, 88% of the patients had a satisfactory objective outcome. The mean arc of flexion was from 27 to 131 degrees.

In 2005, Mighell and coauthors43 presented a series of six elderly women with a chronic fracture dislocation treated with the Coonrad-Morrey total elbow replacement. At a mean follow-up of 6 years (range, 2 to 10 years), three patients had no pain, two had moderate pain, and one had severe pain. The American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons score was five times better (P < 0.001) and the mean flexion arc increased from 33 to 121 degrees (P < 0.001) after operation.

COMPLICATIONS

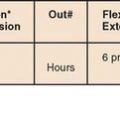

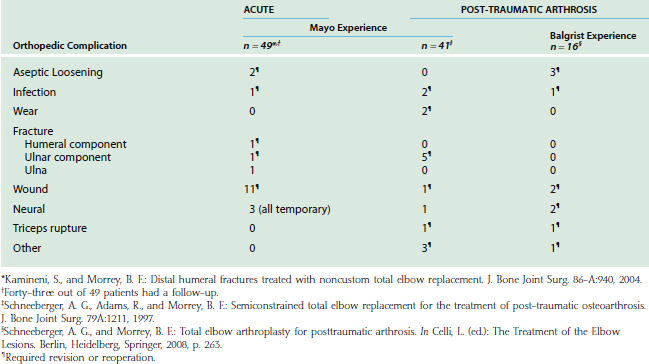

The complications for the Mayo and the Balgrist experience are shown in Table 57-1. Of the 49 patients with an acute fracture, 35% had a surgical complication.34 There were 14 patients with a single complication, and three with two complications; 10 of them required additional procedures. Wound problems occurred in 11 cases: three patients required decompression of a hematoma, two had secondary closure to treat a wound dehiscence, one patient had removal of a prominent Kirschner wire in the olecranon 2 months postoperatively, and in another patient, a wound infection was found to have penetrated into the joint cavity 3 weeks after joint replacement necessitating three débridements and staged exchange revision of the humeral component. There were three (6%) temporary neurologic complications: one sensory and one motoric neuropathy of the ulnar nerve, and one with a reflex sympathetic dystrophy. Two patients had important heterotopic bone formation with abutment of the ectopic bone between the humerus and ulna posteriorly. One ulnar shaft periprosthetic fracture after a fall 1 year after the arthroplasty was successfully treated with a plaster cast.

TABLE 57-1 Major Complications with Total Elbow Arthroplasty After Acute Fracture and Post-traumatic Arthrosis

Of the 41 patients in the post-traumatic group treated at Mayo Clinic, 11 (27%) had at least one major complication, and nine (22%) had an additional operation. This contrasts with the report of Gschwend and colleagues,26 who in 1996, described a complication rate of 43% from a meta-analysis of 22 publications of total elbow replacement. Most of these procedures were performed for rheumatoid arthritis; such cases are usually associated with fewer complications than those in post-traumatic osteoarthrosis cases.

The majority of the complications were of a mechanical cause. Fracture of the ulnar component occurred in five elbows 2 to 9 years (average, 4.3 years) postoperatively. Before breakage, all five patients had an excellent result, with an asymptomatic, essentially normal elbow. The cause of failure was severe noncompliance, such as regular lifting of weights of more than 50 kg in two patients (Fig. 57-9). The revisions involved an average of less than 70 minutes of tourniquet time. There were no operative or delayed complications from the reoperations.

Special concern has been expressed for bushing wear in younger and more active patients.67 To analyze polyethylene wear, all Coonrad-Morrey elbow prostheses performed at the Mayo Clinic from 1981 through 2000 for various indications (34% for trauma-related con-ditions) were retrospectively reviewed.39 Out of 919 patients, only 12 (1.3%) had undergone an isolated exchange of the articular bushings as a result of polyethylene wear. Seven out of these 12 cases had post-traumatic arthrosis. Nine had extensive deformity. The bushings were revised at an average of 8 years after implantation. Polyethylene wear did not seem to be a major problem at the Mayo Clinic.

Newer implants such as the Latitude (Tornier—Zirst, Montbonnot, France, Fig. 57-10) or the Discovery (Biomet, Warsaw, IN) have other polyethylene-metal designs aiming to increase longevity of the polyethylene and to allow higher loads on the prosthesis. Follow-up of these new designs will show whether the different contact surfaces of these new designs will succeed, or if eventually larger amounts of wear debris will result.

At Balgrist, there were eight patients (50%) with 10 complications requiring seven revisions. One patient with a prior Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection had recurrence of the infection after a clinical infection-free period of 5 years. He required staged revision, resulting in an excellent result. Two wounds were successfully revised for aseptic, prolonged wound drainage of more than 7 days. Because the soft tissue envelope is thin around the elbow, wound problems probably increase the risk of infection. For this reason, the authors believe that aggressive wound management is important. The two patients with wound revisions had an uneventful recovery without development of an infection. Loosening was found in two humeral and two ulnar components of three patients, resulting in a loosening rate of 19%. Ulnar loosening was attributed to impingement between the anterior flange of the humeral component and a long coronoid process in one patient (see Fig. 57-4). Another case of early loosening occurred in a patient with possible persistence of a previously present low-grade infection.

Inadequate cementation was observed in two humeral components in the Balgrist series; one of them was found loose at follow-up. In both cases with inadequate cementing, an anterograde cementing technique was used with direct injection of the cement using a syringe contrary to the recommendations of the manufacturer that advise to use an injecting system with retrograde insertion of the cement. Retrograde insertion of cement improves the degree of cement filling and the holding strength of the implants.16 Since 1998, an advanced cementing technique was used at Balgrist, resulting consistently in adequate cementation, and no cases of loosening were observed since then.

In 2000, Hildebrand and coauthors29 reported progressive radiolucent lines after a mean follow-up of 4 years in 5 out of 15 patients treated with the Coonrad-Morrey total elbow prosthesis for traumatic or post-traumatic conditions. These radiolucent lines were found more frequently around methylmetacrylate precoated ulnar components than around those covered with sintered beads. As previously mentioned, the surface of the ulnar component had been modified from sintered beads to a precoat in 1995. Owing to above-mentioned fatigue fractures and some observations of radiolucent lines, the surface treatment was modified in 2000 to the currently used plasma spray coating, improving the cement fixation strength and the mechanical stability.

This experience contrasts to that of most other series of post-traumatic osteoarthrosis that are still complicated by a certain rate of loosening despite the use of semiconstrained devices.38 However, no loosening was observed by Figgie and colleagues17 in their series of nine semiconstrained triaxial prostheses with custom-designed stems. Gschwend and associates25 reported that after a mean of 4 years (maximum, 14 years), loosening of the GSB III prosthesis had occurred in two of 26 patients. Baksi4 reported only four loose implants out of 79 cases treated for post-traumatic ankylosis or instability with an own semiconstrained device followed for an average of 9.6 years (range, 2 to 13.5 years).

1 Allieu Y., Marck G., Chammas M., Desbonnet P., Raynaud J.P. Allogreffes d’articulation totale du coude dans les pertes de substance ostéo-articulaire post-traumatiques étendues. Résultats à 12 ans de recul. Rev. Chir. Orthop. Reparatrice Appar. Mot. 2004;90:319.

2 Armstrong A.D., Yamaguchi K. Total elbow arthroplasty and distal humerus elbow fractures. Hand Clin. 2004;20:475.

3 Askew L.J., An K.-N., Morrey B.F., Chao E.Y.S. Isometric elbow strength in normal individuals. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1987;222:261.

4 Baksi D.P. Sloppy hinge prosthetic elbow replacement for post-traumatic ankylosis or instability. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1998;80-B:614.

5 Blaine T.A., Adams R., Morrey B.F. Total elbow arthroplasty after interposition arthroplasty for elbow arthritis. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2005;87-A:286.

6 Brumfield R.H.Jr., Kuschner S.H., Gellman H., Redix L., Stevenson D.V. Total elbow arthroplasty. J. Arthroplasty. 1990;5:359.

7 Bryan R.S., Morrey B.F. Extensive posterior exposure of the elbow: A triceps-sparing approach. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1982;166:188.

8 Cheng S.L., Morrey B.F. Treatment of the mobile, painful arthritic elbow by distraction interposition arthroplasty. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2000;82-B:233.

9 Cobb T.K., Morrey B.F. Total elbow replacement as primary treatment for distal humeral fractures in elderly patients. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1997;79A:826.

10 Davis R.F., Weiland A.J., Hungerford D.S., Moore J.R., Volenec-Dowling S. Nonconstrained total elbow arthroplasty. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1982;171:156.

11 Dee R. Nonimplantation salvage of failed reconstructive procedures of the elbow. In: Morrey B.F., editor. The Elbow and Its Disorders. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Co.; 1993:690.

12 Dee R. Total replacement arthroplasty of the elbow for rheumatoid arthritis. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1972;54B:88.

13 DeLee J.C. Fractures and dislocations of the hip. In: Rockwoood C.A.Jr., Green D.P., Bucholz R.W., Heckman J.D., editors. Rockwood and Green’s Fractures in Adults. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1996:1687.

14 Delloye C., Cornu O., Dubuc J.E., Vincent A., Barbier O. Reconstruction du coude par allogreffe massive ostéo-articulaire totale: échec précoce par instabilité. Rev. Chir. Orthop. Reparatrice Appar. Mot. 2004;90:360-364.

15 Ewald F.C., Jacobs M.A. Total elbow arthroplasty. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1984;182:137.

16 Faber K.J., Cordy M.E., Milne A.D., Chess D.G., King G.J., Johnson J.A. Advanced cement technique improves fixation in elbow arthroplasty. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1997;334:150.

17 Figgie H.E.III, Inglis A.E., Ranawat C.S., Rosenberg G.M. Results of total elbow arthroplasty as a salvage procedure for failed elbow reconstructive operations. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1987;219:185.

18 Frankle M.A., Herscovici D.Jr., DiPasquale T.G., Vasey M.B., Sanders R.W. A comparison of open reduction and internal fixation and primary total elbow arthroplasty in the treatment of intraarticular distal humerus fractures in women older than age 65. J. Orthop. Trauma. 2003;17:473.

19 Froimson A.I., Silva J.E., Richey D. Cutis arthroplasty of the elbow joint. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1976;58A:863.

20 Gambirasio R., Riand N., Stern R., Hoffmeyer P. Total elbow replacement for complex fractures of the distal humerus. An option for the elderly patient. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2001;83-B:974.

21 Garcia J.A., Mykula R., Stanley D. Complex fractures of the distal humerus in the elderly. The role of total elbow replacement as primary treatment. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2002;84-B:812.

22 Garrett J.C., Ewald F.C., Thomas W.H., Sledge C.B. Loosening associated with GSB hinge total elbow replacement in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1977;127:170.

23 Gill D.R.J., Morrey B.F. The Coonrad-Morrey total elbow arthroplasty in patients who have rheumatoid arthritis. A ten to fifteen-year follow-up study. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1998;80-A:1327.

24 Gschwend N., Loehr J., Ivosevic-Radovanovic D., Scheier H., Munzinger U. Semi-constrained elbow prosthesis with special reference to the GSB III prosthesis. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1988;232:104.

25 Gschwend N., Scheier H., Bähler A., Simmen B. GSB III elbow. In: Ruther W., editor. The Elbow, Endoprosthetic Replacement and Non-endoprosthetic Procedures. Berlin: Springer Verlag; 1996:83.

26 Gschwend N., Simmen B.R., Matejovsky Z. Late complications in elbow arthroplasty. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1996;5:86.

27 Hastings H.2nd, Theng C.S. Total elbow replacement for distal humerus fractures and traumatic deformity: results and complications of semiconstrained implants and design rationale for the Discovery Elbow System. Am. J. Orthop. 2003;32(9 Suppl.):20.

28 Helfet D.L., Schmerling G.J. Bicondylar intra-articular fractures of the distal humerus in adults. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1993;292:26.

29 Hildebrand K.A., Patterson S.D., Regan W.D., MacDermid J.C., King G.J.W. Functional outcome of semiconstrained total elbow arthroplasty. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2000;82-A:1379.

30 Hughes R.E., Schneeberger A.G., An K.-N., Morrey B.F., O’Driscoll S. Reduction of triceps muscle force after shortening of the distal humerus: A computational model. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1997;6:444.

31 Inglis A.E., Pellicci P.M. Total elbow replacement. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1980;62A:1252.

32 John H., Rosso R., Neff U., Bodoky A., Regazzoni P., Harder F. Operative treatment of distal humeral fractures in the elderly. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1994;76B:793.

33 Jupiter J.B., Neff U., Holzach P., Allgöwer M. Intercondylar fractures of the humerus. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1985;67-A:226.

34 Kamineni S., Morrey B.F. Distal humeral fractures treated with noncustom total elbow replacement. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2004;86-A:940.

35 Kamineni S., Morrey B.F. Distal humeral fractures treated with noncustom total elbow replacement. Surgical technique. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2005;87-A(Suppl. 1(Pt 1)):41.

36 Kasten M.D., Skinner H.B. Total elbow arthroplasty. Clin. Orthop. 1993;290:177.

37 Knight R.A., Zandt L.V. Arthroplasty of the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1952;34A:610.

38 Kraay M.J., Figgie M.P., Inglis A.E., Wolfe S.W., Ranawat C.S. Primary semiconstrained total elbow arthroplasty. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1994;76B:636.

39 Lee B.P., Adams R.A., Morrey B.F. Polyethylene wear after total elbow arthroplasty. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2005;87-A:1080.

40 Lowe L.W., Miller A.J., Allum R.L., Higginson D.W. The development of an unconstrained elbow arthroplasty. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1984;66B:243.

41 McAuliffe J.A., Burkhalter W.E., Ouellette E.A., Carneiro R.S. Compression plate arthrodesis of the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1992;74B:300.

42 McKee M.D., Pugh D.M.W., Richards R.R., Pedersen E., Jones C., Schemitsch E.H. Effect of humeral condylar resection on strength and functional outcome after semiconstrained total elbow arthroplasty. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2003;85-A:802.

43 Mighell M.A., Dunham R.C., Rommel E.A., Frankle M.A. Primary semi-constrained arthroplasty for chronic fracture-dislocations of the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2005;87-B:191.

44 Morrey B.F. Post-traumatic contracture of the elbow: Operative treatment including distraction arthroplasty. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1990;72A:601.

45 Morrey B.F. Fractures of the distal humerus: role of elbow replacement. Orthop. Clin. North. Am. 2000;31:145.

46 Morrey B.F., Adams R.A., Bryan R.S. Total replacement for post-traumatic arthritis of the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1991;73B:607.

47 Morrey B.F., Adams R.A. Semi-constrained elbow replacement arthroplasty: Rationale, technique, and results. In: Morrey B.F., editor. The Elbow and Its Disorders. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Co.; 1993:648.

48 Morrey B.F., Adams R.A. Semi-constrained elbow replacement for distal humeral nonunion. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1995;77B:67.

49 Morrey B.F., Askew L.J., An K.-N., Chao E.Y. A biomechanical study of normal functional elbow motion. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1981;63A:872.

50 Morrey B.F., Askew L.J., An K.-N. Strength function after elbow arthroplasty. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1988;234:43.

51 Morrey B.F., Bryan R.S., Dobyns J.H., Linscheid R.L. Total elbow arthroplasty: A five-year experience at the Mayo Clinic. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1981;63A:1050.

52 Muller L.P., Kamineni S., Rommens P.M., Morrey B.F. Primary total elbow replacement for fractures of the distal humerus. Oper. Orthop. Traumatol. 2005;17:119.

53 O’Driscoll S.W., An K.-N., Korinek S., Morrey B.F. Kinematics of semiconstrained total elbow arthroplasty. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1992;74B:297.

54 O’Neill O.R., Morrey B.F., Tanaka S., An K.-N. Compensatory motion in the upper extremity after elbow arthrodesis. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1992;281:89.

55 Pritchard R.W. Anatomic surface elbow arthroplasty: A preliminary report. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1979;179:223.

56 Ramsey M.L., Adams R.A., Morrey B.F. Instability of the elbow treated with semiconstrained total elbow arthroplasty. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1999;81-A:38.

57 Ray P.S., Kakarlapudi K., Rajsekhar C., Bhamra M.S. Total elbow arthroplasty as primary treatment for distal humeral fractures in elderly patients. Injury. 2000;31:687.

58 Scalise J.J., DeSilva S.P. Intraarticular distal humerus fracture complicated by osteogenesis imperfecta treated with primary total elbow arthroplasty: a case report. J. Surg Orthop. Adv. 2006;15:95.

59 Schneeberger A.G., Adams R., Morrey B.F. Semiconstrained total elbow replacement for the treatment of post-traumatic osteoarthrosis. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1997;79A:1211.

60 Schneeberger A.G., Hertel R., Gerber C. Total elbow replacement with the GSB III prosthesis. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9:135.

61 Schneeberger A.G., Meyer D.C., Yian E.H. Coonrad-Morrey total elbow replacement for primary and revision surgery: A 2 to 7.5 year follow-up study. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg.. 2007;16(3 Suppl):47.

62 Schneeberger A.G., Morrey B.F. Total elbow arthroplasty for posttraumatic arthrosis. In: Celli L., editor. The Treatment of the Elbow Lesions. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2008:263.

63 Soni R.K., Cavendish M.E. A review of the Liverpool elbow prosthesis from 1974 to 1982. J. Bone Joint Surg.. 1984;66B:248.

64 Souter W.A., Nicol A.C., Paul J.P. Anatomical trochlear stirrup arthroplasty of the rheumatoid elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1985;67B:676.

65 Tsuge K., Murakami T., Yasunaga Y., Kanaujia R.R. Arthroplasty of the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1987;69B:116.

66 Urbaniak J.R., Black K.E.Jr. Cadaveric elbow allografts: A six-year experience. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1985;197:131.

67 Wright T.W., Hastings H. Total elbow arthroplasty failure due to overuse, C-ring failure, and/or bushing wear. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14:65.

68 Zuckerman J.D., Lubliner J.A. Arm, elbow and forearm injuries. In: Zuckerman J.D., editor. Orthopaedic Injuries in the Elderly. Baltimore: Urban & Schwarzenberg; 1990:345.