CHAPTER 60 Retinal detachment and PVR

Epidemiologic considerations and terminology

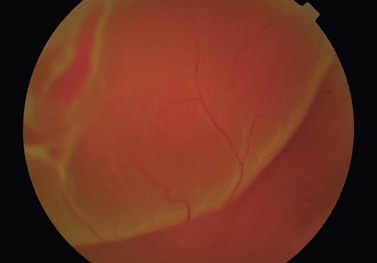

In the majority of cases, the retinal detachment is due to fluid which gains access to the subretinal space via a retinal hole, so called rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (RRD) (Fig. 60.1). In non-rhegmatogenous detachment the separation arises from serous exudation, or for other reasons, and will not be considered further in this chapter.

RRD affects about one in 10 000 adults annually1, and has a higher incidence in myopes2, pseudophakes3, and following trauma4.

Anatomical considerations

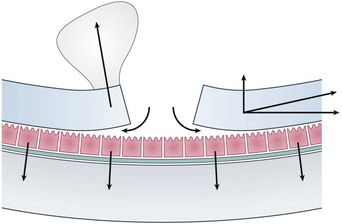

The subretinal space is a potential one, normally kept dry by the pumping action of RPE cells. If the rate of fluid flow through a retinal hole is greater than the rate at which it can be pumped out, then RRD occurs. The balance between ingress and outflow of fluid can be affected by a number of different factors (Fig. 60.2). Dynamic traction from the vitreous, for example following a PVD, can rapidly accelerate the progression of retinal detachment. Similarly increased concavity in the case of a posterior staphyloma, combined with a presumed reduction in the quality of the RPE pump in high myopes, can produce retinal detachments from macular holes, which do not otherwise occur in macular hole patients.

Retinal holes can be classified into three groups: (i) round holes; (ii) traction, or ‘U’ tears; and (iii) other breaks. Round holes are very common, but rarely lead to RRD5. They are usually associated with patches of lattice degeneration. In a small subset of young myopic patients, they can cause slowly progressive retinal detachment, accounting for approximately 5% of patients requiring treatment. The majority of RRDs are caused as a result of one or more traction, or ‘U’ tears secondary to a PVD. The most common location for such tears is the superior temporal quadrant.

Fundamental principles

The principle of treatment for RRD is prevention of fluid flow through the retinal hole. This can be achieved by closing then sealing the hole. Closure of the hole refers to the apposition of retina and underlying RPE, closing the gap between them. Sealing of the retinal hole refers to the creation of a permanent adhesion between the retina and the underlying tissue. As current methods of sealing require the passage of time, it is usual to combine sealing with temporary closure, thus keeping the edges of the hole apposed until the adhesion has developed. Buckles work by creating an indentation of the sclera, thereby closing holes, but also creating a convex surface in favor of re-attachment6. Tamponade with gas or silicone oil blocks the retinal hole by surface tension, preventing fluid flow through it. Both cryotherapy and laser create tissue injury which results in chorioretinal adhesion 5–10 days later.

Preoperative assessment

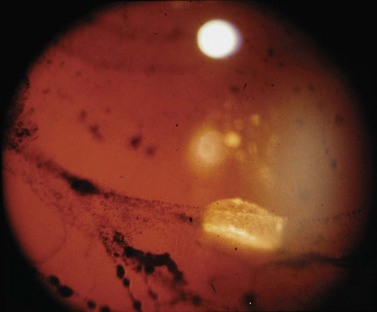

The aim of preoperative assessment is to confirm the diagnosis, identify the retinal holes, and plan the most appropriate surgical technique. Although the vast majority of patients presenting with retinal detachments have RRD, the possibility of an exudative retinal detachment must always be considered, particularly if a retinal hole is not seen. The presence of pigment cells in the anterior vitreous (’tobacco dust’) is strongly correlated with the presence of a retinal hole, though a similar sign can occur as a result of iris trauma during cataract surgery (Fig. 60.3). Examination of the anterior segment is important, as it may give clues to the etiology, but is also helpful in determining the quality of the view that the surgeon will get during surgery.

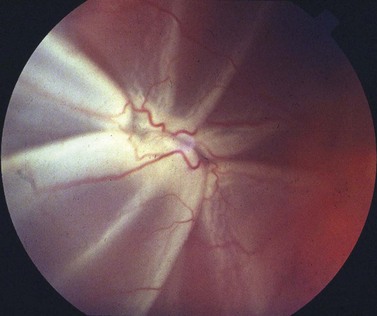

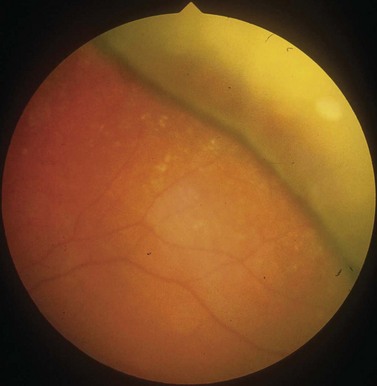

An assessment of the degree of proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR) should also be made. The proximity of ‘star folds’ near retinal breaks may mean that vitrectomy is required (Fig. 60.4). Contraction of the vitreous base may be an indication for an encircling buckle.

Operation techniques

Scleral buckling

Scleral buckling is a surgical procedure in which indentation of the scleral surface is achieved by suturing a silicone support to the sclera, thus sealing the retinal break, relieving vitreoretinal traction and reducing the flow of fluid into the subretinal space (Fig. 60.5). When combined with retinopexy, chorioretinal adhesion results maintaining retinal reattachment even when the indent subsequently fades.

Vitrectomy

Following the introduction of air in the treatment of retinal detachment by Ohm in 1911, the use of intraocular gases has become indispensable in the treatment of many vitreoretinal conditions. Pure SF6 expands to about twice its volume in the first 24–48 hours after surgery due to nitrogen from human tissue entering the intravitreal bubble in response to the partial pressure gradient7. SF6 remains within a vitrectomized eye for approximately 10–14 days, being absorbed more slowly than air due to its high molecular weight, low diffusion coefficient, and low water solubility7. The non-expansile concentration of SF6 is 18%. C3F8 has a longer duration of action than SF6, expands to four times its volume, and lasts for 55–65 days in the vitrectomized eye. The non-expansile concentration of C3F8 is 12%7. Prolonged tamponade may also be achieved using silicone oils, which are linear synthetic organic–inorganic polymers consisting of a chain made of repeating units of siloxane [-Si-O-] units.

Controversy persists about the value of supplementary scleral buckling, and the SPR study gave conflicting results on this issue. The addition of a buckle (which was at the discretion of the surgeon) resulted in better success rates in the pseudophakic/aphakic group but not in the phakic group8. In the treatment of inferior break retinal detachment, some smaller studies have also failed to show an advantage in combining vitrectomy with scleral buckling over vitrectomy alone9–11. Combining scleral buckling with vitrectomy is technically more demanding and is associated with an increased risk of choroidal hemorrhage12, requires a longer operating time13 and has all the associated complications of a scleral buckle, i.e. exposure, refractive change, diplopia, possible decreased retinal blood flow, and risk of anterior segment ischemia14–19.

Although most of the current literature refers to the use of 20-gauge vitrectomy in the treatment of retinal detachment, more recently surgeons have been using small gauge sutureless vitrectomy systems for treating this condition. Initial anecdotal reports suggested that 25-gauge vitrectomy for retinal detachment was associated with a lower success rate, but this may have been learning-curve related. More recent publications show acceptable success rates for 25-gauge and the results of 23-gauge systems are awaited20.

Intraoperative complications

The risk of intraoperative complications will largely depend on the surgical technique employed.

Postoperative complications

In addition, the use of intraocular gases is associated with raised intraocular pressure7. Raised intraocular pressure is more likely following an injection of an expansile concentration of gas. The incidence of elevated pressure ranges from 26–59% however this is usually transient and can be managed medically in most cases7.

The clinical complications observed with silicone oil use are thought to occur either from direct toxicity or secondary to the migration and subsequent sequestration of silicone oil in ocular tissues and the associated inflammatory response21. Sequestration of silicone oil within the retina and posterior migration in the optic nerve has also been observed21,22. Silicone oil is frequently used as a tamponading agent in the treatment of complicated retinal detachments, however its benefits must be weighed against the risk of the complications associated with its use for example cataract, band keratopathy, secondary glaucoma and potentially reduced visual acuity.

Failure of surgery

Reported primary success rates for RRD repair ranges from 64 to 91%13,23,24. Retinal redetachment following initial surgery may occur secondary to the development of PVR, the failure of treatment, e.g. missed or partially treated breaks, or the development of new retinal breaks. A meta-analysis comparing surgical outcomes following pneumatic retinopexy, scleral buckling, and vitrectomy did not find a statistical difference between the final attachment rates of these surgical techniques24.

Risk factors

Conclusive evidence regarding the significance of risk factors for failure of primary retinal detachment repair is difficult to find. Studies investigating risk factors show a number of inconsistencies relating to the different study designs, inclusion criteria and the surgical techniques employed. Furthermore the majority of studies are retrospective. Reported preoperative characteristics that may be associated with an increased risk of surgical failure include the duration of symptoms, the extent of retinal detachment and the involvement of inferior quadrants, an absence of detectable retinal breaks, high myopia, and hypotony. In addition, risk factors associated with the development of PVR including aphakia, uveitis, the presence of vitreous hemorrhage, the presence of PVR preoperatively, raised intraocular pressure, and increased age will also increase the risk of primary failure25.

PVR

PVR is defined as the growth and contraction of membranes within the vitreous cavity and on both surfaces of the retina following rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. These membranes can exert traction and reopen previously closed breaks, create new breaks, and distort or obscure the macula26. A revised classification of PVR was produced in 199127, which was based on that published in 1983 with additional staging of the location and type of grade C PVR (Table 60.1).

| (a) General classification of PVR | |

|---|---|

| Grade | Features |

| A | Vitreous haze; pigment clumps; pigment clusters on inferior retina |

| B | Wrinkling of inner retinal surface; retinal breaks with rolled or irregular edges; retinal stiffness; vessel tortuosity; decreased mobility of vitreous |

| CP1-12 | Posterior to the equator; focal, diffuse or circumferential full-thickness rigid retinal folds*; subretinal strands* |

| CA1-12 | Anterior to equator; focal, diffuse or circumferential full-thickness rigid retinal folds*; subretinal strands*; anterior displacement; condensed vitreous with strands |

| (b) Sub-classification of Grade C PVR | ||

|---|---|---|

| Type | Location (in relation to equator) | Features |

| Focal | Posterior | Starfold posterior to vitreous base |

| Diffuse | Posterior | Confluent starfolds posterior to vitreous base; optic disc may not be visible |

| Subretinal | Posterior/anterior | Proliferations under the retina: annular strands near disc; linear strands; moth-eaten-appearing sheets |

| Circumferential | Anterior | Contraction along posterior edge of vitreous base with central displacement of the retina; peripheral retina stretched; posterior retina in radial folds |

| Anterior displacement | Anterior | Vitreous base pulled anteriorly by proliferative tissue; peripheral retinal trough; ciliary processes may be stretched, may be covered by membrane; iris may be retracted. |

* Expressed in the number of clock hours involved.

PVR is the most common cause of failure following retinal detachment surgery, with a reported incidence of 5.1–11.7%28. Where there is a final failure of retinal detachment surgery, in over 75% of cases PVR is responsible28. Elucidation of the risk factors and pathogenesis of PVR has informed research aimed at developing pharmacologic adjuncts to surgical management. Although there have been some successes these agents have failed make a significant impact clinically. The addition of 5-fluorouracil (5FU) and low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) to the infusion fluid at the time of vitrectomy improved success rates in high risk cases; however, in established PVR this combination did not have a positive treatment effect29,30. In unselected primary detachments, combined 5FU and LMWH appeared to reduce final visual acuity in macula-sparing detachments and this adjunctive combination may have only a limited role in PVR management31. Similarly, a perioperative infusion of daunorubicin, although shown to reduce re-operations in established PVR, has not gained widespread acceptance32. Corticosteroids modify cellular proliferation and reduce inflammation, and might therefore be a useful adjunct in the management of PVR33. Three small studies of intravitreal triamcinolone (TA) in established PVR showed a possible beneficial effect34–36. In addition to ocular adjuncts, some success has been achieved with systemic agents such as isotretinoin (Accutane), which improved retinal reattachment rates following complex retinal detachment repair37.

Treatment of retinal detachments with PVR can be distilled down to three basic principles:

Counteraction of traction

Membrane peeling

Peeling of epiretinal membranes relieves tangential traction that results in retinal folds. Identification of preretinal membranes may be aided with the use of adjuncts for example,triamcinolone, trypan blue and brilliant blue38. Epiretinal membranes can be engaged using a vitreoretinal pick, usually by gently moving the pick along the trough of a retinal fold. Once engaged a pair of membrane forceps may be used to peel the membrane off the retinal surface. Movement should commence at the posterior retina moving anteriorly because the retina is thicker posteriorly and provides stronger countertraction than the thinner anterior retina.

Scleral buckle

A circumferential buckle may be used as a way of relieving anterior traction caused by contraction of the vitreous base. In order to achieve sufficient height to the buckle the eye needs to be softened. In a vitrectomized eye, drainage of aqueous fluid through a corneal paracentesis or vitreous cavity fluid via a pars plana needle is usually sufficient to create the space required. In an unvitrectomized eye, aqueous paracentesis may not create enough space and additional procedures may be require, for example, drainage of subretinal fluid, aspiration of vitreous fluid, or limited vitrectomy. In a study of 95 eyes, a combined approach of vitrectomy and scleral buckling resulted in retinal reattachment in 75% of patients with severe PVR (grade D1–D3) compared to a much lower success rate of 19–23% using scleral buckling alone39.

Retinotomy and retinectomy

This technique is associated with a poor anatomic and visual outcome and an increased incidence of hypotony40. In a retrospective study of 302 patients who underwent retinectomy, 51% achieved retinal reattachment following one procedure, but only 11.9% had a final visual acuity of greater than 6/24. Using silicone oil as a tamponading agent appears to decrease the risk of postoperative hypotony40.

Long-acting endotamponade

The clinical dilemma of whether to use gas or silicone oil as a tamponade agent when treating cases of retinal detachment with PVR was addressed in the Silicone Study. This was a multi-centered, randomized clinical trial designed to evaluated the benefits and risks of using a long-acting gas bubble or silicone oil as an intraocular tamponade following vitrectomy in eyes with severe PVR (grade C3 or greater). When the use of silicone oil was compared with that of a longer-acting gas, C3F841, there was no statistical difference in the anatomic success rate (73% vs. 64%) or in the number achieving a final visual acuity of greater than or equal to 5/200 (43% vs. 45%) at 18 months. More long-term follow-up (36 months) suggested an advantage favoring C3F8 in achieving complete posterior retinal reattachment (83% vs. 60%, P = 0.045). In a later study, use of silicone oil was associated with a better visual outcome in patients with anterior PVR; however, the anatomic success rate was no better than that observed with C3F842.

Assessment of surgery

Reported primary success rates for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment repair ranges from 64 to 91%43–45. The consequences of failure as a result of PVR on visual function are well documented, with only 11–25% of patients achieving a visual acuity of 20/10041; however, the functional results following failure without PVR are less well known.

Visual acuity is widely recognized as a major determinant of visual function and as such ophthalmologists rely primarily on visual acuity to define surgical success, and to plan patient management. It is increasingly recognized, however, that patients are more interested in how interventions affect their well being than unidimensional indicators of visual function46. Nevertheless, poor visual acuity has been associated with decreased performance of many activities of daily living, poor cognitive ability, and ultimately poorer health related quality of life (QOL)47,48.

1 Tornquist R, Bodin L, Tornquist P. Retinal detachment. A study of a population-based patient material in Sweden 1971–1981. IV. Prediction of surgical outcome. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 1988;66:637-642.

2 Burton TC. The influence of refractive error and lattice degeneration on the incidence of retinal detachment. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1989;87:143-155. discussion 155–7

3 Tuft SJ, Minassian D, Sullivan P. Risk factors for retinal detachment after cataract surgery: a case–control study. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:650-656.

4 Johnston PB. Traumatic retinal detachment. Br J Ophthalmol. 1991;75:18-21.

5 Byer NE. What happens to untreated asymptomatic retinal breaks, and are they affected by posterior vitreous detachment? Ophthalmology. 1998;105:1045-1049. discussion 1049–50

6 Michels RG, Thompson JT, Rice TA, et al. Effect of scleral buckling on vector forces caused by epiretinal membranes. Am J Ophthalmol. 1987;104:667-670.

7 Chang S. Intraocular gases. In: Wilkinson CP, editor. Retina. St. Louis: Mosby Inc.; 2001:2147-2161.

8 Heimann H, Bartz-Schmidt KU, Bornfeld N, et al. Scleral buckling versus primary vitrectomy in rhegmatogenous retinal detachment: a prospective randomized multicenter clinical study. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:2142-2154.

9 Wickham L, Connor M, Aylward GW. Vitrectomy and gas for inferior break retinal detachments: are the results comparable to vitrectomy, gas, and scleral buckle? Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88:1376-1379.

10 Sharma A, Grigoropoulos VG, Williamson TH. Management of primary rhegmatogenous retinal detachment with inferior breaks. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;88:1372-1375.

11 Weichel ED, Martidis A, Fineman MS, et al. Pars plana vitrectomy versus combined pars plana vitrectomy–scleral buckle for primary repair of pseudophakic retinal detachment. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:2033-2040.

12 Tabandeh H, Sullivan P, Smahliuk P. Suprachoroidal haemorrhage during pars plana vitrectomy – risk factors and outcomes. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:236-242.

13 Hakin KN, Lavin MJ, Leaver PK. Primary vitrectomy for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1993;231:344-346.

14 Flindall RJ, Norton EW, Curtin VT, et al. Reduction of extrusion and infection following episcleral silicone implants and cryopexy in retinal detachment surgery. Am J Ophthalmol. 1971;71:835-837.

15 Fison PN, Chignell AH. Diplopia after retinal detachment surgery. Br J Ophthalmol. 1987;71:521-525.

16 Domniz YY, Cahana M, Avni I. Corneal surface changes after pars plana vitrectomy and scleral buckling surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2001;27:868-872.

17 Hayashi H, Hayashi K, Nakao F, et al. Corneal shape changes after scleral buckling surgery. Ophthalmology. 1997;104:831-837.

18 Kwartz J, Charles S, McCormack P, et al. Anterior segment ischaemia following segmental scleral buckling. Br J Ophthalmol. 1994;78:409-410.

19 Yoshida A, Feke GT, Green GJ, et al. Retinal circulatory changes after scleral buckling procedures. Am J Ophthalmol. 1983;95:182-188.

20 Acar N, Kapran Z, Altan T, et al. Primary 25-gauge sutureless vitrectomy with oblique sclerotomies in pseudophakic retinal detachment. Retina. 2008;28:1068-1074.

21 Wickham L, Asaria RH, Alexander R, et al. Immunopathology of intraocular silicone oil: enucleated eyes. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91:253-257.

22 Eller AW, Friberg TR, Mah F. Migration of silicone oil into the brain: a complication of intraocular silicone oil for retinal tamponade. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;129:685-688.

23 Heimann H, Bornfeld N, Friedrichs W, et al. Primary vitrectomy without scleral buckling for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1996;234:561-568.

24 Saw SM, Gazzard G, Wagle AM, et al. An evidence-based analysis of surgical interventions for uncomplicated rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2006;84:606-612.

25 Kon CH, Asaria RHY, Occleston NL, et al. Risk factors for proliferative vitreoretinopathy after primary vitrectomy: a prospective study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:506-511.

26 The Retina Society Terminology Committee. The classification of retinal detachment with proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Ophthalmology. 1983;90:121-125.

27 Machemer R, Aaberg TM, Freeman HM, et al. An updated classification of retinal detachment with proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1991;112:159-165.

28 Charteris DG, Sethi CS, Lewis GP, et al. Proliferative vitreoretinopathy – developments in adjunctive treatment and retinal pathology. Eye. 2002;16:369-374.

29 Asaria RH, Kon CH, Bunce C, et al. Adjuvant 5-fluorouracil and heparin prevents proliferative vitreoretinopathy: Results from a randomized, double-blind, controlled clinical trial. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:1179-1183.

30 Charteris DG, Aylward GW, Wong D, et al. A randomized controlled trial of combined 5-fluorouracil and low-molecular-weight heparin in management of established proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:2240-2245.

31 Wickham L, Bunce C, Wong D, et al. Randomized controlled trial of combined 5-fluorouracil and low-molecular-weight heparin in the management of unselected rhegmatogenous retinal detachments undergoing primary vitrectomy. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:698-704.

32 Wiedemann P, Hilgers RD, Bauer EA, et al. Adjunctive daunorubicin in the treatment of proliferative vitreoretinopathy: results of a multicenter clinical trial. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;126:550-559.

33 Sanders DR, Kraff MC. Steroidal and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents. Effect on postsurgical inflammation and blood–aqueous humor barrier breakdown. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984;102:1453-1456.

34 Munir WM, Pulido JS, Sharma MC, et al. Intravitreal triamcinolone for treatment of complicated proliferative diabetic retinopathy and proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Can J Ophthalmol. 2005;40:598-604.

35 Jonas JB, Hayler JK, Panda-Jonas S. Intravitreal injection of crystalline cortisone as adjunctive treatment of proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:1064-1067.

36 Cheema RA, Peyman GA, Fang T, et al. Triamcinolone acetonide as an adjuvant in the surgical treatment of retinal detachment with proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2007;38:365-370.

37 Chang YC, Hu DN, Wu WC. Effect of oral 13-cis-retinoic acid treatment on postoperative clinical outcome of eyes with proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146:440-446.

38 Li K, Wong D, Hiscott P, et al. Trypan blue staining of internal limiting membrane and epiretinal membrane during vitrectomy: visual results and histopathological findings. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87:216-219.

39 Hanneken AM, Michels RG. Vitrectomy and scleral buckling methods for proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Ophthalmology. 1988;95:865-869.

40 Blumenkranz MS, Azen SP, Aaberg T, et al. Relaxing retinotomy with silicone oil or long-acting gas in eyes with severe proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Silicone Study Report 5. The Silicone Study Group. Am J Ophthalmol. 1993;116:557-564.

41 Silicone Study Group. Vitrectomy with silicone oil or perfluoropropane gas in eyes with severe proliferative vitreoretinopathy: results of a randomized clinical trial. Silicone Study Report 2. Arch Ophthalmol. 1992;110:780-792.

42 Diddie KR, Azen SP, Freeman HM, et al. Anterior proliferative vitreoretinopathy in the silicone study: Silicone study report 10. Ophthalmology. 1996;103:1092-1099.

43 Halberstadt M, Brandenburg L, Sans N, et al. Analysis of risk factors for the outcome of primary retinal reattachment surgery in phakic and pseudophakic eyes. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd. 2003;220:116-121.

44 Heimann H, Zou X, Jandeck C, et al. Primary vitrectomy for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment: an analysis of 512 cases. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2006;244:69-78.

45 Thompson JA, Snead MP, Billington BM, et al. National audit of the outcome of primary surgery for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. II. Clinical outcomes. Eye. 2002;16:771-777.

46 Scott IU, Smiddy WE, Feuer W, et al. Vitreoretinal surgery outcomes: Results of a patient satisfaction/functional status survey. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:795-803.

47 Scott IU, Schein OD, West S, et al. Functional status and quality of life measurement among ophthalmic patients. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994;112:329-335.

48 Marx MS, Werner P, Cohen-Mansfield J, et al. The relationship between low vision and performance of activities of daily living in nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:1018-1020.