11 Resuscitation in Pregnancy

• Displace the gravid uterus off the great vessels either manually or with a left lateral tilt to avoid aortocaval compression.

• Gain intravenous access above the diaphragm.

• Preoxygenate with 100% oxygen before intubation in anticipation of a more rapid onset of hypoxemia.

• In a pregnant woman, hands for cardiopulmonary resuscitation, chest tubes, and defibrillator paddles should be placed higher on the chest wall.

• Cardioversion and defibrillation will not harm the fetus.

• When the uterus is palpable above the umbilicus and the mother is in cardiac arrest, perform cesarean section immediately.

• Continue cardiopulmonary resuscitation during and after perimortem cesarean section and consider therapeutic hypothermia in a comatose patient with return of spontaneous circulation.

• For an Rh-negative woman who has vaginal bleeding after trauma, administer Rh immunoglobulin (RhoGAM): a 50-mcg dose in the first trimester and a 300-mcg dose in the second or third trimester.

• In any pregnant woman at more than 24 weeks’ gestation who suffers trauma to the abdomen, fetal monitoring should be initiated as soon as possible and be maintained for 4 to 6 hours.

Scope

Resuscitation of a pregnant woman is an infrequent event. Cardiac arrest statistics are difficult to quantify, but cardiac arrest reportedly occurs in roughly 1 in 30,000 near-term pregnancies.1 More recent data suggest an increase in maternal mortality from cardiac arrest, with frequency rates of 1 in 20,000.2 In the event of cardiac arrest in a pregnant woman, two lives must be resuscitated. Quick, decisive management is paramount for the livelihood of the mother and her unborn child. Knowing exactly what to do and acting quickly ensure the best possible outcome for the mother and her unborn child.

Anatomy and Physiology

What are generally considered abnormal vital signs in nonpregnant people may actually be within the normal range for a pregnant woman. In gravid females, the heart rate and respiratory rate are increased. In the second trimester, blood pressure is decreased by 5 to 15 mm Hg, but it returns to normal near term. Hypoxemia occurs earlier in pregnant patients because of diminished reserve and buffering capacity. Pregnant patients have a slight respiratory alkalosis—PCO2 of 30 mm Hg and pH of 7.43—that must be taken into account when interpreting arterial blood gas values. Central venous pressure decreases in pregnancy to a third-trimester value of 4 mm Hg.3

Differential Diagnosis

Pregnant women are generally young and healthy. The rare cardiac arrest in a gravid female may be due to venous thromboembolism, severe pregnancy-induced hypertension, amniotic fluid embolism, or hemorrhage. In addition to such pregnancy-related problems, pregnant women are not exempt from common conditions that affect the general population. Trauma and sepsis may lead to cardiopulmonary failure and the need for maternal resuscitation. Box 11.1 lists key etiologic factors leading to cardiac arrest in pregnant patients.4

Box 11.1

Major Causes of Cardiac Arrest During Pregnancy*

From Mallampalli A, Powner DJ, Gardner MO. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation and somatic support of the pregnant patient. Crit Care Clin 2004;20:748.

Hemorrhage

During routine vaginal delivery, the average blood loss is 500 mL. Excessive blood loss or postpartum hemorrhage complicates 4% of vaginal deliveries.5 Common causes of hemorrhage around the time of delivery are uterine atony (excessive bleeding with a large relaxed uterus after delivery), vaginal or cervical tears, retained fragments of placenta, placenta previa, placenta accreta, and uterine rupture. Hereditary abnormalities in blood clotting may cause hemorrhage, so inquiries about excessive bleeding, known disorders, and family history are relevant in a patient with excessive bleeding.

Nonhemorrhagic Shock

Causes of nonhemorrhagic obstetric shock—pulmonary embolism, amniotic fluid embolism, acute uterine inversion, and sepsis—are uncommon but are responsible for the majority of maternal deaths in the developed world.6 These conditions must be diagnosed and treated expeditiously. Patients in whom pulmonary embolism is suspected should be administered heparin and then undergo diagnostic imaging. Although fibrinolytic agents are contraindicated in pregnancy, they have been used successfully in patients with life-threatening pulmonary embolism and ischemic stroke. Treatment of amniotic fluid embolism is supportive, the goals being to maintain maternal oxygenation and support blood pressure. Some case reports describe success with the use of cardiopulmonary bypass to treat women suffering from amniotic fluid embolism.

Acute uterine inversion can also cause shock. Cardiovascular collapse complicates approximately half the cases of acute uterine inversion. Classically, the extent of the shock is out of proportion to the blood loss noted. One theory to explain this observation is that a parasympathetic reflex causes neurogenic shock from stretching of the broad ligament or compression of the ovaries (or both) as they are drawn together. Uterine replacement combined with vigorous fluid resuscitation, including blood transfusion as required, should reverse the hypotension.7

Diagnostic Testing

Interventions and Procedures

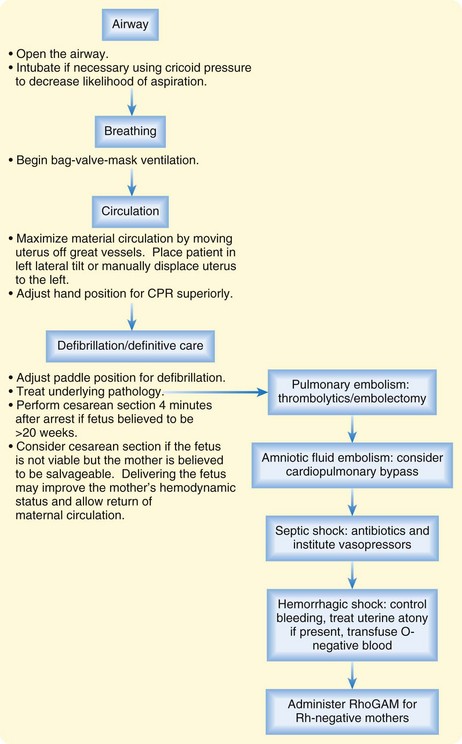

A fundamental principle in treating pregnant women is that fetal well-being depends on maternal well-being. As with all patients in the emergency department (ED), resuscitation starts with the ABCs (airway, breathing, and circulation). One hundred percent oxygen should be administered to the mother early. Hypoxia should be treated aggressively in this patient population because when the mother is hypoxic, oxygen is shunted away from the fetus. Additionally, preoxygenation is important because apnea results in more rapid hypoxia in the setting of pregnancy. Rapid-sequence induction with precautions for aspiration is essential before intubation. Aggressive volume resuscitation, administration of vasopressors if needed, and close attention to the patient’s body position are all very important in the treatment of hypotension in a pregnant patient. Fetal heart monitoring and, ideally, cardiotocographic monitoring should be initiated as soon as possible for patients in the second or third trimester of pregnancy.8

A commercially produced wedge called a Cardiff wedge is available to aid in the resuscitation of pregnant women. It can be placed under the woman’s right side to support her back while she lies in the preferred left lateral tilt position. In the absence of a wedge, a human wedge can be used, with the patient being tilted on the bent knees of a kneeling rescuer. Pillows, towel rolls, and blanket rolls are readily available in EDs and accomplish the same purpose of angling the woman’s back 30 to 45 degrees from the floor (Fig. 11.1). If for some reason the patient must lie on her back, as in the case for adequate cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), a member of the health care team should manually displace the uterus to the left so that it does not rest on the great vessels.

• Move the uterus off the great vessels.

• Adjust the hand position for CPR cephalad to account for displacement of the thoracic contents by the gravid uterus.

• Place one paddle below the right clavicle in the midclavicular line.

• Position the second paddle outside the normal cardiac apex so that it avoids breast tissue.7

Defibrillation energy requirements remain the same (Fig. 11.2).9 Defibrillation will not harm the fetus. ACLS medications should be used as needed. It is reasonable to remove external or internal fetal monitoring devices during electrical shock of the mother because of the possibility of creating an electrical arc to the monitoring equipment, but this is unlikely with the electrical current applied to the maternal thorax. Box 11.2 lists the U.S. Food and Drug Administration categories for the various ACLS drug options during pregnancy.

Box 11.2 Classification of Drugs Used During Pregnancy

If return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) is achieved, effort must be directed at further hemodynamic stabilization. Post–cardiac arrest therapeutic hypothermia has been successful in the setting of early pregnancy and is recommended as for nonpregnant patients.10 In a comatose post–cardiac arrest patient with ROSC, the patient should be cooled as soon as possible and within 4 to 6 hours to 32° C to 34.8° C for a 12-to 24-hour duration to gain the best possible neurologic outcome. If a perimortem cesarean section has not been performed because of gestational age less than 24 weeks, fetal monitoring should be performed during hypothermia in anticipation of bradycardia.11

Perimortem Cesarean Section

The two goals of perimortem cesarean section are to improve the unstable hemodynamics of the mother and minimize morbidity and mortality in the child. If resuscitative efforts, including ACLS algorithms and alleviation of aortocaval compression, fail to improve maternal hemodynamics, perimortem cesarean section must be considered. The likelihood that perimortem cesarean section will result in a living and neurologically normal infant is related to the interval between onset of maternal cardiac arrest and delivery of the infant.12,13 The gestational age of the neonate is also critical. If cesarean section is performed in the ED, it should be done rapidly. Time is of the essence. Fetal viability outside the uterus is best beyond 24 weeks’ gestation, but it is not always possible to know the exact gestational age in the ED. On the basis of case reports, it is recommended that cesarean section be performed in the ED if the gestational age is believed to be more than 20 weeks. At this stage of pregnancy, the fundus is likely to be palpable at or above the level of the umbilicus.

The child should be delivered within 5 minutes of maternal cardiac arrest, so the procedure should be initiated within 4 minutes of failed CPR of the mother. The procedure is summarized in Box 11.3. Maternal CPR should be maintained throughout the procedure to optimize blood flow to the uterus and the mother and should be continued after cesarean section. Once delivery is accomplished, ED personnel should be prepared to resuscitate the neonate. It is important to note that published and anecdotal reports describe return of maternal blood pressure and maternal survival after perimortem cesarean section.14 Successful resuscitation of a pregnant woman and her unborn child requires a coordinated team approach.

Box 11.3 Technique for Perimortem Cesarean Section

NOTE: Have suction available for this procedure because bleeding can be excessive.

1. Ideally, while the emergency physician is preparing for the procedure, a catheter is placed in the bladder and the abdominal wall is prepared with povidone-iodine. However, do not delay the procedure for these activities.

2. Using a No. 10 scalpel, make a midline vertical incision from the umbilicus to the pubis along the linea nigra.

3. Once the peritoneal cavity is open, use bladder retractors and Richardson retractors to improve access to the uterus.

4. Make a short vertical incision in the lower uterine segment just cephalad to the bladder.

5. Extend the uterine incision cephalad with blunt scissors. Place a hand in the uterus to keep the baby from being cut.

7. Suction the mouth and nose, cut and clamp the umbilical cord, and resuscitate the baby.

8. Document Apgar scores at 1, 5, and 10 minutes.

9. If the mother regains vital signs, remove the placenta and repair the uterus and abdominal wall.

10. Consider intramuscular injection of oxytocin into the bleeding uterus.

1 Peters CW, Layon AJ, Edwards RK. Cardiac arrest during pregnancy. J Clin Anesth. 2005;17:229–234.

2 Lewis F, editor. The Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH). Saving mothers’ lives; reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer—2003-2005. The Seventh Report on Confidential Enquiries.

3 Shah AJ, Kilcline BA. Trauma in pregnancy. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2003;21:615–629.

4 Mallampalli A, Powner DJ, Gardner MO. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation and somatic support of the pregnant patient. Crit Care Clin. 2004;20:748.

5 Miller DA. Obstetric hemorrhage. OBFocus High Risk Pregnancy. Available at http://www.obfocus.com/high-risk/bleeding/hemorrhagepa.htm

6 Thomas AJ, Greer IA. Non-hemorrhagic obstetric shock. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2000;14:19–41.

7 O’Grady JP, Pope CS. Malposition of the uterus. eMedicine [serial online] June 5, 2006. Available at http://www.emedicine.com/med/topic3473.htm

8 Luppo CJ. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation: pregnant women are different. AACN Clin Issues. 1997;8:574–585.

9 Nanson J, Elcock D, Williams M, et al. Do physiologic changes in pregnancy change defibrillation energy requirements? Br J Anaesth. 2001;87:237–239.

10 Rittenberger J, Kelly E, Jang D, et al. Successful outcome utilizing hypothermia after cardiac arrest in pregnancy: a case report. Crit Care Med. 2008;63:1354–1356.

11 Vanden Hoek T, Morrison LJ, Shuster M, et al. Part 12: cardiac arrest in special situations: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2010;122:S829–S861.

12 Weber CE. Postmortem cesarean section: review of the literature and case reports. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1971;110:158–165.

13 Oates S, Williams GL, Rees GAD. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation in late pregnancy. BMJ. 1988;297:404–405.

14 Katz V, Balderston K, DeFreest M. Perimortem cesarean delivery: were our assumptions correct? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1916–1920.