Chapter 26 Restless Legs Syndrome in Neurological Disorders

Despite the importance of genetic factors in restless legs syndrome (RLS) (see Chapter 8), environmental factors and acquired conditions are likely to play major roles in determining which individuals develop RLS. They are likely to also affect when RLS symptoms begin. Patients without a positive family history are now classified as having either primary RLS, if no other predisposing condition is found, or secondary RLS, if they concurrently have a condition known to be associated with and likely to cause RLS. At least twenty medically related conditions have been reported in the literature in association with RLS. Most of these are likely to be chance occurrences owing to the past underestimated prevalence of RLS. However, several specific neurological conditions appear to have a “greater-than-chance” occurrence and are discussed in this chapter.

Neuropathy

Numerous forms of neuropathy, including hereditary, diabetic, alcoholic, amyloid, motor neuron disease, poliomyelitis, and radiculopathy, have been associated with RLS.1–14 Investigating the association between RLS and neuropathy, however, has been challenging. The definition of neuropathy varies in studies. Some include neuropathy diagnosed by standard electrophysiological methods, which only detect abnormalities in large-fiber myelinated nerves, whereas others incorporate measures of unmyelinated nerve fibers through skin biopsy or other physiological studies, which in some instances do not have well-established normative data. Depending on the sensitivity of the tests used and the definition of neuropathy used, more patients with neuropathy may be identified and it would not be surprising that two common conditions would overlap by chance alone. Referral bias may also affect results, because neuropathy patients with positive symptoms (RLS or pain) are more likely to seek medical attention than those with pure sensory loss. Moreover, neuropathy and RLS clearly share many features. Symptoms of both conditions are generally worse in the evening and nighttime, both affect primarily the legs and feet, and they share risk factors such as uremia, diabetes, amyloid, and cryoglobulinemia. The two disorders also respond to many of the same therapeutic interventions.

Several series have reported the prevalence of RLS in populations of patients presenting with neuropathy. One retrospective study evaluated 800 diabetic patients for neuropathic features and reported that only 8.8% complained of RLS.3 This was not significantly greater than the 7% RLS prevalence among the control subjects. Interestingly, the percentage of people with type 2 diabetes affected with RLS was significantly higher than those with type 1 diabetes; an association with type 2 diabetes that has been confirmed, particularly in patients with polyneuropathy.15 This difference, however, may have resulted from the older age of the type 2 population. A prospective study evaluating consecutive patients with electrophysiologically diagnosed neuropathy reported that 8 of 154 (5%) meet International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group (IRLSSG) clinical criteria for RLS.6 Symptoms improved with L-dopa in five patients. Interestingly, the RLS symptoms in two patients with Lyme disease–associated neuropathy improved after antibiotic treatment. Although the authors thought that this represented an association of neuropathy and RLS, the 5% prevalence is actually lower than the percentage reported in surveys of RLS symptoms in the general population. More recent studies, however, have suggested that the frequency in general polyneuropathy may be higher.16

Specific forms of neuropathy may incur different risks for the development of RLS. Gemignani and colleagues16 reported that 10 of 27 (37%) of patients with Charcot-Marie-Tooth type II (CMT II), an axonal neuropathy, had RLS, whereas RLS was not seen in any of the 17 patients with CMT I, a demyelinating neuropathy.16 The presence of RLS in CMT II correlated with other positive sensory symptoms such as pain. The same group reported a high prevalence of RLS among patients with essential mixed cryoglobulinemia, which also typically causes a painful neuropathy.7 Another group reported a high prevalence of RLS in a kindred with familial amyloid neuropathy.2 In several instances, RLS symptoms preceded the diagnosis of the neuropathy.

Studies that have tried to detect neuropathy in populations of patients presenting with RLS have found a quite robust association. In a case series of eight patients with “idiopathic” RLS, Iannoccone and coworkers4 found that all subjects had at least one peripheral nerve abnormality among a battery of peripheral nerve tests including electrophysiology, quantitative sensory testing, and sural nerve biopsy. In a series of 98 RLS patients, 37 demonstrated evidence of neuropathy by standard electromyelography (EMG)/nerve conduction velocity (NCV) techniques.5 Most of these had mild to moderate sensory axonal neuropathies; however, the exact etiologies varied. Many of these patients had no evidence of neuropathy on clinical examination. The presence of neuropathy was much higher in patients who did not have a family history of RLS compared with those who did have a family history—22 of 31 (71%) versus 15 of 67 (24%), p <.001. Another four of those nine nonfamilial RLS with normal EMG examinations had very low ferritin levels, possibly accounting for their RLS. These findings are consistent with, but do not prove, that neuropathy can cause a secondary form of RLS.

The phenotype of neuropathic RLS may be slightly different from idiopathic RLS.5,8 Several studies have found that patients with neuropathic RLS present at an older age and tend to have more severe RLS. In addition, the RLS appears to progress more rapidly. A large number of patients with neuropathic RLS reached maximum symptom intensity within 1 year from the initial symptom onset, which is unusual in idiopathic cases. Idiopathic RLS tended to begin with sensations between the ankle and knee, whereas neuropathic RLS tended to initially occur distally or randomly throughout the leg.5 Neuropathic RLS may also have accompanying neuropathic pain, which is often burning and more superficial. The painful component and the urge to move, however, are seldom differentiated by the patient. Finally, neuropathic RLS patients are less like to develop augmentation with chronic dopaminergic treatment.17 Neuropathic RLS patients, however, might be more easily managed with dopaminergic medications over long periods of time.

Small-fiber neuropathy, determined by punch skin biopsy, has also been reported in patients presenting with RLS.8 There is reason to believe that this population of nerve fibers may be important in RLS. These fibers are preferentially and predominantly affected in diseases such as diabetes, uremia, amyloidosis, and cryoglobulinemia—precisely the same conditions that have been implicated as risk factors in RLS. Furthermore, damage to small-caliber sensory nerve fibers is associated with neuropathic pain, and studies have suggested that the pain associated with neuropathy may be important in RLS. Among 22 consecutive patients with established RLS, 3 had a predominantly large-fiber neuropathy, 3 had a predominantly small-fiber neuropathy, and 2 had mixed neuropathies. Several additional patients did not fulfill diagnostic criteria for small-fiber neuropathy but had prominent structural abnormalities in epidermal nerve fibers such as nerve fiber swellings, which often precede the development of small-fiber neuropathy.18 RLS patients with neuropathy did not have a positive family history for RLS, although their RLS symptoms were associated with pain, tended to be more severe, and began at an older age. Other studies have found that, in general polyneuropathy and diabetic neuropathy, a small-fiber neuropathy is more likely to be associated with RLS.11,13

In addition to length-dependent forms of peripheral neuropathy, other forms of peripheral nerve injury such as radiculopathy19 and spinal stenosis20 have also been associated with RLS. The underlying feature of these conditions may be the presence of pain. Pain has been a unifying theme among studies investigating neuropathy in RLS patients, and the specific causes of neuropathy associated with RLS are typically painful. Interestingly, dopamine, the primary target of RLS treatments, has also been implicated in pain processing. High levels of dopaminergic activity in the striatum have been shown to reduce neuronal encephalin content and lead to a compensatory rise in μ-opioid receptor expression.21,22 A role for dopamine as an inhibitor of pain perception is further supported by its efficacy in relieving the pain associated with breast cancer, bone metastases,23,24 herpes zoster,25 painful Parkinson’s disease,26 and diabetic neuropathy.27

Despite these phenotypical differences, it is currently not possible to discern the role that peripheral nerve abnormalities play in RLS, and neurologists differ in their assessment of neuropathy in RLS patients. Some centers may obtain EMG/NCV in all RLS patients, although their usefulness is admittedly debatable in cases with an early age at onset and a strong family history. One could also expand this evaluation to include an assessment of small unmyelinated nerve fibers through punch skin biopsies. If a neuropathy is discovered, a proper investigation of underlying and potentially treatable conditions is warranted. Many patients presenting with painful neuropathy are now appreciated to have occult diabetes or impaired glucose tolerance. In many of these patients, improvement of the hyperglycemia parallels improvements in neuropathy symptoms. It is possible that the same holds true for those subjects with neuropathic RLS, although this remains unanswered. It has also been suggested that all patients presenting with neuropathic sensory symptoms should be screened for RLS, which may occur quite commonly with such presentations.28

The clinical similarities between neuropathic and idiopathic RLS suggest a common pathogenesis. Both animal models29–31 and clinical movement disorders32,33 suggest that permanent perturbation of central nervous system neurotransmitter function can follow a peripheral nervous system injury. Recent studies in patients with primary RLS demonstrate that they share similarities to neuropathic pain patients such as an exaggerated perception to pin-prick sensation34 or exaggerated spinal reflexes.35 Modulation of gain in spinal nociceptive transmission is controlled in two principal ways—from ascending afferent input and/or modulation by supraspinal descending pathways. Thus, the association between peripheral neuropathy, particularly painful peripheral neuropathy, and RLS may reflect central sensitization changes induced by peripheral nerve injury. Better understanding of the exact relationship between RLS and neuropathy awaits more detailed epidemiological data, and a better understanding of RLS pathogenesis as a whole, but recent studies emphasize that the relationship is likely to be frequent and important.

Parkinson’s Disease

RLS and Parkinson’s disease (PD) both respond to dopaminergic treatments, both show dopaminergic abnormalities on functional imaging,36,37 and both are associated with periodic limb movements of sleep.38 It is now known that the pathology of the two dopaminergically treated diseases are very different and, in regard to brain iron status, actually quite opposite.39 Before the development of IRLSSG criteria, some studies,40,41,44 but not others,42,54 found a higher prevalence of RLS in patients with PD.

In a survey of 303 consecutive PD patients, it was reported that 20.8% of all patients with PD met the diagnostic criteria for RLS.43 Very similar findings have been found by other groups that have studied mostly white populations45,46 (R. Chaudhuri, personal communication). Despite this high number of cases, there are several caveats that tend to lessen its clinical significance. The RLS symptoms in PD patients are often ephemeral, are usually not severe, and can be confused with other PD symptoms such as wearing off dystonia, akathisia, or internal tremor. Furthermore, most patients in this survey group were not previously diagnosed with RLS and few recognized that this was separate from other PD symptoms.43

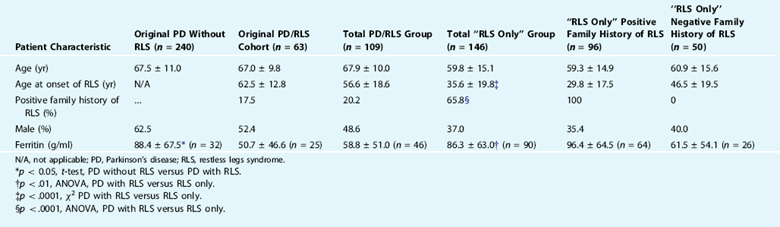

After determining the prevalence of RLS in PD in this survey group,43 the researchers next evaluated for factors that could predict RLS in this population and determined that only lower serum ferritin levels predicted RLS symptoms in the PD population (Table 26-1). RLS did not correlate with duration of PD, age, Hoehn and Yahr, gender, dementia, use of L-dopa, use of dopamine agonists, history of pallidotomy, or history of deep brain stimulation. PD symptoms preceded RLS symptoms in 35 of 41 (85.4%; χ2 = 20.5, p <.0001) cases in which patients confidently remembered the initial onset of both symptoms, a finding now replicated in another study from Japan.46 Only 22 of 109 (20.2%) of all RLS/PD patients reported a positive family history of RLS, compared with more than 60% of our non-PD RLS population. The serum ferritin was also lower in the PD/RLS group compared with the idiopathic RLS group. In the cases with PD who did have a family history of RLS, the RLS symptoms usually preceded PD and generally resembled typical RLS. In short, our results do not suggest that RLS is a forme fruste or a risk factor for the subsequent development of PD but rather that PD is a risk factor for RLS, which might constitute an underrecognized nonmotor feature of PD.

Krishnan and colleagues47 evaluated the prevalence of RLS in patients with PD compared with normal control subjects in a population from India. They found that 10 of 126 cases of PD (7.9%) versus only 1 of 128 control subjects (0.8%, p = .01) reported RLS. PD patients with RLS were older and reported more depression. Although both prevalence values are lower than in U.S. reports, the difference in RLS prevalence between PD and control subjects is similar. This probably reflects baseline epidemiology that suggests RLS is less common in non-white populations. Likewise, Tan and coworkers48 in a mostly Chinese population in Singapore found only a single case of RLS of 125 patients presenting with PD. They also reported a very low RLS prevalence in the general population.49

Evaluating the prevalence of PD in populations presenting with RLS is problematic, because PD symptoms would usually be more overt and precipitate an evaluation. Banno and coworkers40 however, reported that “extrapyramidal disease or movement disorders” were previously diagnosed in 17.5% of male RLS patients versus 0.2% of male controls and in 23.5% of female patients versus 0.2% of female controls (p < .05). They do not clarify whether they thought that these prior diagnoses were correct or truly represented a different disease. In an abstract, Fazzini and colleagues50 reported that 19 of 29 RLS patients had PD symptoms. In the author’s experience, RLS does not predispose to the development of PD; however, definitive prospective epidemiology does not exist for this scenario.

It is possible that RLS in PD is related to the dopaminergic therapy given to PD patients. Such treatment can cause augmentation (iatrogenic worsening) in RLS. On the other hand, surgery for PD has been reported either to alleviate51 or cause deterioration52 of RLS symptoms. In some cases, worsening may be due to the decrease in dopaminergic treatment post surgery.

Essential Tremor

We have also identified several large families with concurrent ET and RLS. In fact, the family on which the 2p chromosome ET gene locus was identified has over 30 members who also complained of RLS.53 There was a high, but not perfect, co-segregation between RLS and ET in this and other families.

An association between RLS and ET has also been observed by some researchers54 but not by others.55 This is consistent with the population studied, because similar to our study, population presenting with RLS are not likely to have significantly increased pathological tremor, but populations presenting with ET do frequently have RLS.

Ataxia

Abele and associates56 reported that RLS was seen in 28% of 58 subjects with genetic ataxias (SCA1, SCA2, SCA3). This was greater than the 10% reported by their control population. The average age at onset of RLS was 49 years. RLS did not correlate with the presence of neuropathy or with CAG expansion length but did correlate with the duration of neurological symptoms normally associated with those conditions.

A small case series suggested that PLMS and RLS might be more common in SCA6 hereditary ataxia.57

Schols and associates58 reported that RLS was seen in 45% of patients with SCA3 (Machado-Joseph disease) but was uncommon in other genetic ataxias. They thought that RLS tended to be more common in patients with neuropathy, but it could also be seen without neuropathy. Family members without SCA3 did not have any RLS symptoms. A separate report described RLS symptoms in a family with intermediate-length CAG repeats for SCA3.59 Investigation of CAG repeats in RLS populations has not revealed any increased60 or abnormal61 distribution of these genomic elements.

There are no reports of treatment for RLS in these populations.

Miscellaneous

Tourette syndrome (TS) is defined by tics, which are promulgated from a premonitory sensation. This clearly has some similarities to RLS, and in the authors’ experience, leg tics are very difficult to distinguish from RLS. Both conditions also involve dopaminergic systems. Lesperance and coworkers62 examined RLS and other TS comorbidities in 144 probands with TS or chronic tics and their parents. RLS was present in 10% of probands and 23% of parents with no gender differences. RLS in probands was linked significantly to maternal RLS but not paternal RLS, suggesting that a maternal RLS factor may contribute to the variable expression of TS. Another family with TS and RLS showed an increased susceptibility to akathisia with neuroleptic treatments.63 Periodic limb movement of sleep and reduced sleep time were also found in children with TS.63 There is however no good evidence to suggest that populations presenting with RLS have higher rates of TS.64

Evers and Stogbauer65 reported a single family with a comorbidity of Huntington’s disease and idiopathic RLS. All family members investigated and affected by RLS are also affected by Huntington’s disease, but not vice versa. The author has not appreciated this association, although Huntington’s disease patients appear to be very susceptible to akathisia with tetrabenazine or neuroleptic medications.

1. Callaghan N. Restless legs syndrome in uremic neuropathy. Neurology. 1966;16:359-361.

2. Salvi F, et al. Restless legs syndrome and nocturnal myoclonus: Initial clinical manifestation of familial amyloid polyneuropathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1990;53:522-525.

3. O’Hare JA, Abuaisha F, Geoghegan M. Prevalence and forms of neuropathic morbidity in 800 diabetics. Irish J Med Sci. 1994;163:132-135.

4. Iannaccone S, et al. Evidence of peripheral axonal neuropathy in primary restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord. 1995;10:2-9.

5. Ondo W, Jankovic J. Restless legs syndrome: Clinicoetiologic correlates. Neurology. 1996;47:1435-1441.

6. Rutkove SB, Matheson JK, Logigian EL. Restless legs syndrome in patients with polyneuropathy. Muscle Nerve. 1996;19:670-672.

7. Gemignani F, et al. Cryoglobulinaemic neuropathy manifesting with restless legs syndrome. J Neurol Sci. 1997;152:218-223.

8. Polydefkis M, et al. Subclinical sensory neuropathy in late-onset restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 2000;55:1115-1121.

9. Skomro RP, et al. Sleep complaints and restless legs syndrome in adult type 2 diabetics. Sleep Med. 2001;2:417-422.

10. Gemignani F, Marbini A. Restless legs syndrome and peripheral neuropathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;72:555.

11. Gemignani F, Brindani F, Negrotti A, et al. Restless legs syndrome and polyneuropathy. Mov Disord. 2006;21:1254-1257.

12. Kilfoyle DH, Dyck PJ, Wu Y, et al. Myelin protein zero mutation His39Pro: Hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy with variable onset, hearing loss, restless legs and multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2006;77:963-966.

13. Gemignani F, Brindani F, Vitetta F, et al. Restless legs syndrome in diabetic neuropathy: A frequent manifestation of small fiber neuropathy. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2007;12:50-53.

14. Merlino G, Fratticci L, Valente M, et al. Association of restless legs syndrome in type 2 diabetes: A case-control study. Sleep. 2007;30:866-871.

15. Gemignani F, et al. Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2 with restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 1999;52:1064-1066.

16. Ondo W, et al. Long-term treatment of restless legs syndrome with dopamine agonists. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:1393-1397.

17. Lauria G, et al. Axonal swellings predict the degeneration of epidermal nerve fibers in painful neuropathies. Neurology. 2003;61:631-636.

18. Walters AS, Wagner M, Hening WA. Periodic limb movements as the initial manifestation of restless legs syndrome triggered by lumbosacral radiculopathy. Sleep. 1996;19:825-826.

19. LaBan MM, et al. Restless legs syndrome associated with diminished cardiopulmonary compliance and lumbar spinal stenosis—A motor concomitant of “Vesper’s curse”. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1990;71:384-388.

20. George SR, Kertesz M. Met-enkephalin concentrations in striatum respond reciprocally to alterations in dopamine neurotransmission. Peptides. 1987;8:487-492.

21. Steiner H, Gerfen CR. Role of dynorphin and enkephalin in the regulation of striatal output pathways and behavior. Exp Brain Res. 1998;123:60-76.

22. Nixon DW. Use of L-dopa to relieve pain from bone metastases [letter]. N Engl J Med. 1975;292:647.

23. Dickey RP, Minton JP. Levodopa relief of bone pain from breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1972;286:843.

24. Kernbaum S, Hauchecorne J. Administration of levodopa for relief of herpes zoster pain. JAMA. 1981;246:132-134.

25. Quinn NP, et al. Painful Parkinson’s disease. Lancet. 1986;1:1366-1369.

26. Ertas M, et al. Use of levodopa to relieve pain from painful symmetrical diabetic polyneuropathy. Pain. 1998;75:257-259.

27. Nineb A, Rosso C, Dumurgier J, et al. Restless legs syndrome is frequently overlooked in patients being evaluated for polyneuropathies. Eur J Neurol. 2007;14:788-792.

28. Braune S, Schady W. Changes in sensation after nerve injury or amputation: The role of central factors. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1993;56:393-399.

29. Curtis R, et al. Retrograde axonal transport of ciliary neurotrophic factor is increased by peripheral nerve injury. Nature. 1993;365:253-255.

30. Jenkins R, Hunt SP. Long-term increase in the levels of c-jun m RNA and Jun protein like immunoreactivity in motor and sensory neurons following axon damage. Neurosci Lett. 1991;129:107-110.

31. Jankovic J. Post-traumatic movement disorders: Central and peripheral mechanisms [comment]. Mov Disord 1994;44:2006-2014.

32. Koller WC, Wong GF, Lang A. Posttraumatic movement disorders: A review. Mov Disord. 1989;4:20-36.

33. Stiasny-Kolster K, Magerl W, Oertel WH, et al. Static mechanical hyperalgesia without dynamic tactile allodynia in patients with restless legs syndrome. Brain. 2004;127:773-782.

34. Bara-Jimenez W, Aksu M, Graham B, et al. Periodic limb movements in sleep: State-dependent excitability of the spinal flexor reflex. Neurology. 2000;54:1609-1616.

35. Ruottinen HM, et al. An FDOPA PET study in patients with periodic limb movement disorder and restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 2000;54:502-504.

36. Turjanski N, Lees AJ, Brooks DJ. Striatal dopaminergic function in restless legs syndrome: 18F-dopa and 11C-raclopride PET studies. Neurology. 1999;52:932-937.

37. Wetter TC, et al. Sleep and periodic leg movement patterns in drug-free patients with Parkinson’s disease and multiple system atrophy. Sleep. 2000;23:361-367.

38. Connor JR, et al. Neuropathological examination suggests impaired brain iron acquisition in restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 2003;61:304-309.

39. Horiguchi J, et al. (Sleep-wake complaints in Parkinson’s disease). Rinsho Shinkeigaku—Clin Neurol. 1990;30:214-216.

40. Banno K, et al. Restless legs syndrome in 218 patients: Associated disorders. Sleep Med. 2000;1:221-229.

41. Lang AE. Restless legs syndrome and Parkinson’s disease: Insights into pathophysiology. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1987;10:476-478.

42. Paulson G. Is restless legs a prodrome to Parkinson’s disease? Mov Disord. 1997;12(suppl 1):68.

43. Ondo WG, Vuong KD, Jankovic J. Exploring the relationship between Parkinson disease and restless legs syndrome. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:421-424.

44. Braga-Neto P, et al. Snoring and excessive daytime sleepiness in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Sci. 2004;217:41-45.

45. Gomez-Esteban JC, Zarranz JJ, Tijero B, et al. Restless legs syndrome in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2007;22:1912-1916.

46. Nomura T, Inoue Y, Nakashima K. Clinical characteristics of restless legs syndrome in patients with Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Sci. 2006;250:39-44.

47. Krishnan PR, Bhatia M, Behari M. Restless legs syndrome in Parkinson’s disease: A case-controlled study. Mov Disord. 2003;18:181-185.

48. Tan EK, Lum SY, Wong MC. Restless legs syndrome in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Sci. 2002;196:33-36.

49. Tan EK, et al. Restless legs syndrome in an Asian population: A study in Singapore. Mov Disord. 2001;16:577-579.

50. Fazzini E, Diaz R, Fahn S. Restless legs in Parkinson’s disease-clinical evidence for underactivity of catecholamine neurotransmission [abstract]. Ann Neurol 1989;26:142.

51. Driver-Dunckley E, Evidente VG, Adler CH, et al. Restless legs syndrome in Parkinson’s disease patients may improve with subthalamic stimulation. Mov Disord. 2006;21:1287-1289.

52. Parra J, Brocalero-Camacho A, Sancho J, et al. (Severe restless legs syndrome following bilateral subthalamic stimulation to treat a patient with Parkinson’s disease.). Rev Neurol. 2006;42:766-767.

53. Higgins JJ, et al. Evidence that a gene for essential tremor maps to chromosome 2p in four families. Mov Disord. 1998;13:972-977.

54. Larner AJ, Allen CM. Hereditary essential tremor and restless legs syndrome. Postgrad Med J. 1997;73(858):254.

55. Walters AS, et al. A preliminary look at the percentage of patients with restless legs syndrome who also have Parkinson disease, essential tremor or Tourette syndrome in a single practice. J Sleep Res. 2003;12:343-345.

56. Abele M, et al. Restless legs syndrome in spinocerebellar ataxia types 1, 2, and 3. J Neurol. 2001;248:311-314.

57. Boesch SM, Frauscher B, Brandauer E, et al. Restless legs syndrome and motor activity during sleep in spinocerebellar ataxia type 6. Sleep Med. 2006;7:529-532.

58. Schols L, et al. Sleep disturbance in spinocerebellar ataxias: Is the SCA3 mutation a cause of restless legs syndrome? Neurology. 1998;51:1603-1607.

59. van Alfen N, et al. Intermediate CAG repeat lengths (53,54) for MJD/SCA3 are associated with an abnormal phenotype. Ann Neurol. 2001;49:805-807.

60. Desautels A, Turecki G, Montplaisir J, et al. Analysis of CAG repeat expansions in restless legs syndrome. Sleep. 2003;26:1055-1057.

61. Konieczny M, Bauer P, Tomiuk J, et al. CAG repeats in restless legs syndrome. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2006;141:173-176.

62. Lesperance P, et al. Restless legs in Tourette syndrome. Mov Disord. 2004;19:1084.

63. Muller N, et al. Tourette’s syndrome associated with restless legs syndrome and akathisia in a family. Acta Neurol Scand. 1994;89:429-432.

64. Voderholzer U, et al. Periodic limb movements during sleep are a frequent finding in patients with Gilles de la Tourette’s syndrome. J Neurol. 1997;244:521-526.

65. Evers S, Stogbauer F. Genetic association of Huntington’s disease and restless legs syndrome? A family report. Mov Disord. 2003;18:226-228.