Chapter 24 Restless Legs Syndrome and Periodic Limb Movements in the Elderly With and Without Dementia

The 2002 National Institutes of Health Diagnosis and Workshop Conference on restless legs syndrome (RLS)1 suggested that RLS may be manifested differently in geriatrics. I review the prevalence and factors associated with RLS in the elderly and then discuss the variegated presentation of RLS in older adults, particularly those with dementing illnesses.

Restless Legs Syndrome: Prevalence and Associated Factors

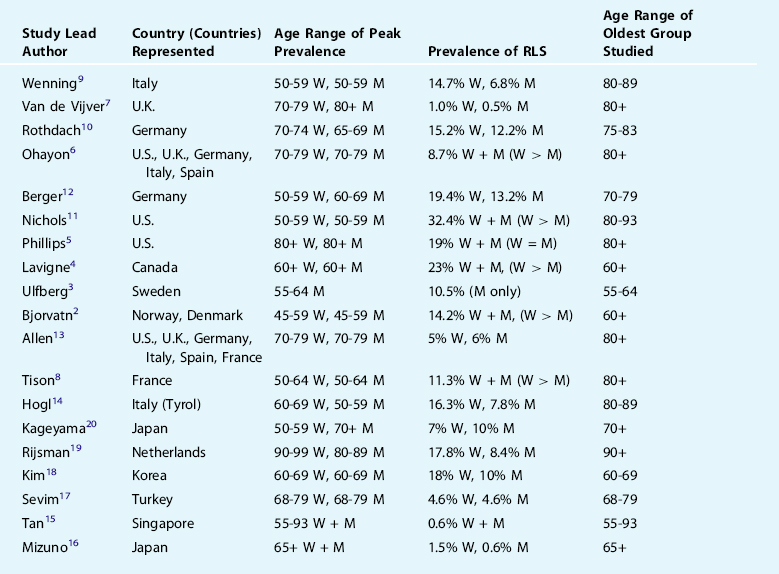

Epidemiologic studies have shown conflicting evidence regarding whether the prevalence of RLS increases with age2–20 (Table 24-1). Interpretation of age effects in such population-based work is complicated by the fact that the upper age limit varies among studies, and various studies use different definitions of RLS, with some employing face-to-face or telephone interviews and full International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group (IRLSSG) criteria or mail questionnaires with either single or multiple items. The large variability in prevalence among studies is evident in Table 24-1. Most, but not all, suggest a female predominance of the condition, and the large variability across studies could also reflect the geographically and genetically diverse populations studied, including those from North America, northern and southern Europe, and Asia. The issue as to whether RLS shows age dependence (defined as higher prevalence simply as a function of chronological age) remains unclear. Conversely, the aging effect might also be characterized as age related (defined as a specific age span of vulnerability).21

Within the limits of descriptive research, epidemiologic studies such as those in Table 24-1 also allow for an appreciation of how age interacts with risk factors for RLS. Conditions commonly associated with RLS include hypertension and cardiovascular disease, relationships seen in many,3,6,12,22 but not all,2,14,17,18 as well as diabetes and/or peripheral neuropathy, similarly seen in many,5,6,12,22,23 but not all,7,10,17,18 studies. These relationships were demonstrated statistically to be independent from age, but because cardiovascular disease and deficient glucose metabolism both increase with aging, these generally positive associations have considerable relevance to the elderly population. Another condition common in old age, arthritis, has been associated with RLS in several studies6,22 but also with some conflicting evidence.7 Similar conflicting evidence in population-based data has been noted for hypothyroidism7,12 and renal disease,7,14,17 and at least one study has reported associations between RLS and gastroesophageal reflux22 and daytime sweating24 in both older men and women.

Lifestyle factors may also hold relevance as risk factors for RLS in the elderly population. For example, older persons are more likely to have a sedentary lifestyle and a number of studies have documented that lack of physical activity is associated with RLS,5 although curiously there are also data to suggest that more frequent exercise exerts a risk for RLS6 or that exercise was unrelated.14,18 Smokers have been shown to incur a greater risk for RLS in most studies examined5,6,10,12,17,18,22 with relatively few conflicting data.14 Caffeine6 and alcohol6 may also represent risks for RLS, but alcohol use was also reported to be protective5,18 or exert no influence.17 In all of these studies, it must be recalled that the assignment of putative risk is based on cross-sectional, observational findings. Longitudinal data would be required to appreciate whether a preexisting risk factor, operating in individuals without any history of RLS, might predict eventual development of the condition. It should also be stressed that although most of these studies showing relationships between RLS and a putative risk factor controlled for age, none attempted to demonstrate that the association between age and RLS was due to a particular risk factor. Such an approach would require demonstration that chronological age was no longer a significant risk when particular risk factor(s) were controlled statistically. No study has yet to present such data.

Issues of causality are nowhere more apparent than when describing associations between depressed mood and RLS.25 Such findings would be particularly relevant for the geriatric population who endorse items frequently related to depression at higher rates than populations of middle-aged or younger adults. Relationships between RLS and general indices of lower mental health5,6 or depressive symptoms2,3,7,10,13,17,22,26,27 have been shown in many population-based studies. The most parsimonious assumption of causality in these exclusively cross-sectional studies is not that depression predisposes for RLS but rather that RLS symptoms, if left untreated, may lead to depression in the older person. Paradoxically, another interpretative possibility is that, because virtually none of these studies has controlled for simultaneous use of psychoactive medications, including tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or neuroleptics, which are themselves risk factors for RLS6,7,10 and/or periodic leg movements in sleep (PLMS),28 the associations could be secondary to the use of such medications.

Given the high prevalence of anemia in elderly populations, altered iron metabolism associated with RLS and aging requires special consideration, and several surveys have noted such associations (see Chapters 9 and 10).17,22 O’Keeffe29 was the first to note that elderly individuals with RLS were likely to show low serum ferritin levels. Although overt anemia and reduced serum iron may not always co-occur with RLS, neuroimaging and cerebrospinal fluid studies have suggested that total brain iron concentrations are lowered in RLS, findings that are compatible with modified blood-brain transport.30,31 Because anemia is highly prevalent in the elderly, it is well within the range of possibility that iron metabolism moderates the high prevalence of RLS in the aged. A surprisingly small number of studies have assessed this in elderly populations. O’Keeffe32 replicated the original finding with a small additional case series suggesting that serum ferritin levels less than 50 ng/ml were significantly more likely in elderly patients with recent-onset RLS, but other population-based studies demonstrate a more complicated situation. One study demonstrated that RLS were not accompanied by low levels of serum ferritin or by higher levels of soluble transferrin receptor, but mid-range levels of serum iron and transferrin saturation appeared protective for RLS.33 Neither serum ferritin nor hemoglobin levels less than 2 SDs below gender-expected values were significant factors in RLS in a German study in the age range of 20 to 79 years.12 In a northern Italian elderly population (South Tyrol), however, higher soluble transferrin receptor levels (often seen in early-stage anemia) and lower serum iron levels were correlated with RLS.14 Another study showed that cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) ferritin levels in older, late-onset RLS patients were not related to onset of RLS symptoms.34 That study also showed that elderly patients had higher levels of CSF ferritin than younger patients.34 Taken together, these studies imply that iron deficiency may not be a relevant risk factor for RLS manifesting in elderly populations, unless the RLS also had early onset.

The complex relationship between RLS and PLMS is covered elsewhere in this volume (see Chapters 17 and 22). From the aging perspective, it is important to bear in mind that PLMS can occur in many older persons without accompanying RLS symptoms. In elderly populations, the prevalence of PLMS (without reference to RLS) has been reported to be as high as 45%,35 and over 85% of older individuals had a PLMS index over 5.0 across 5 nights of recordings.36 Complaints of poor and/or altered sleep architecture were unrelated to PLMS in many studies.37–39 One study35 found that PLMS were related to nocturnal leg kicking and breathing symptoms but were unrelated to many aspects of sleep disruption (e.g., lower total sleep time, prolonged sleep onset latency); the best correlate of PLMS was the estimated number of awakenings on the recording night. Other studies of older subjects found a relationship between difficulty falling asleep and PLMS40 or a relationship with lower total sleep times and wake after sleep onset.41 By contrast, some studies have suggested no relationships between PLMS and symptoms. Mendelson42 could find no relationships between PLMS arousals and symptoms. Montplaisir and colleagues43 compared with controls, individuals with insomnia, and individuals with hypersomnia and found no differences in PLMS among groups, and Karadeniz and coworkers44 were unable to show changes in macrosleep or microsleep architecture in conjunction with PLMS in insomnia patients ages 40 to 64 years. Hornyak and coworkers.45 found no relationship between PLMS and sleep quality in insomniac patients without RLS. In another study, PLMS were unrelated to polysomnographically defined sleep quality in 70 normal subjects ages 40 to 60 years, although in men a small but significant effect was reported for lower sleep quality in relation to a PLMS index greater than 10.46 When viewed in their totality, these results present a very mixed picture as to the correlates of PLMS in old age in the absence of frank RLS.

Of final note, there is some evidence that polysomnographic features may distinguish PLMS in the elderly. For example, night-to-night variability that has been reported in elderly individuals with PLMS who do not have apparent RLS,36,47–49 and the number of PLMS with arousals or awakenings has been reported to be higher in older age groups.42,50,51 Finally, reduced magnitude of heart rate variability accompanying PLMS in older, relative to younger, subjects has also been reported.52

Restless Legs Syndrome in Dementia

Identification of RLS in dementia patients is challenging. Because reporting of RLS symptoms requires considerable verbal facility, typically lacking in demented patients, it becomes necessary to rely on key signs, including rubbing or massaging legs, high levels of leg motor activity (such as pacing), and indicators of leg discomfort during rest or inactivity and its improvement with activity are compatible with RLS. The presence of such signs during certain times of day (i.e., late afternoon and/or early evening) are also compatible with such a diagnosis. Although not explicitly mentioned in the National Institutes of Health Conference Report, the phenomenon of wandering, a major issue in the behavioral management of dementia patients,53 may represent a manifestation of RLS of considerable import in geriatric care. As a case in point, treatments for wandering typically used in dementia patients may involve dopaminergic antagonism, which might otherwise exacerbate, rather than ameliorate, the wandering behaviors (see Treatment Considerations).

Of all of the behavioral problems associated with dementia, wandering remains one of the most difficult to understand and treat.54,55 Considerable risk occurs when patients wander both inside and outside their homes, and, in the case of the latter, police and other emergency services may become involved.56 From the standpoint of caregivers, nocturnal wandering is the most troubling of all sleep-related behaviors of patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD).55,57 From the standpoint of researchers, understanding the mechanism leading to such behaviors is no less daunting. Much of the research in this area has been purely descriptive, with a focus on mapping the direction of the wandering58 or attempting to discern elements of “escape-like” behavior that may be implicit within the ambulation.59 Duffy and colleagues have offered a seemingly more informed perspective by implying that wandering behaviors may be best understood as a deficit in visual attention circuits that lead to confused visuospatial orientation.60,61 Positron emission tomography (PET) studies62,63 compared wandering and nonwandering AD patients and found reduced dopamine uptake in the caudate and putamen, findings that were related to lowered cerebral glucose utilization in the temporal and frontal, but not parietal, cortex. More recent findings have replicated these results.64 At the most general level, these findings in AD patients who wander parallel neuroimaging studies in RLS patients, who, at least in several studies, evidenced reductions in dopamine terminal storage.65,66 This presupposes dysfunction of the nigrostriatal system in RLS patients, which at best may be a dubious assumption (see the section on parkinsonism).

The statement from the National Institutes of Health Workshop Conference on RLS1 suggested that RLS should be considered in the differential for wandering behavior in a dementia patient. Of more than passing interest is a finding from a carefully done, real-time video monitoring study that analyzed “travel behavior” in nursing home patients and examined time as an independent variable in the occurrence of such behaviors.67 This study reported that the peak occurrence of such apparent wandering took place between 7 P.M. and 9 P.M., which would coincide nicely with a greater likelihood of RLS occurring during that time interval. In any given patient, a history (provided by either patient or, in the case of severe dementia, reliable family members) suggestive of RLS or members of the family with previously diagnosed RLS could also assist in establishing the diagnosis in the dementia patient. At least one retrospective study reported that dementia patients who wandered had lifelong walking behavior whenever under duress.58 Obviously, conditions linked to RLS in the nondemented population (e.g., neuropathy, diabetes, musculoskeletal disease or anemia) that occur in a dementia patient who wanders should prompt consideration of a diagnosis of RLS. Little is known about the specific prevalence of RLS in AD, although one study noted that, at least based on caregiver reports, AD patients were no more likely to have RLS symptoms or leg twitches than were those in a nondemented age-comparison group.68 At least one other recent study69 also presents indirect evidence of a relationship between dementia and RLS. In that work, RLS patients were shown to have impairments in prefrontal cortical functions that were suggested to represent the cumulative effects of sleep deprivation. This can be construed as consistent with the co-occurrence of a cognitive syndrome with RLS symptomatology.

Perhaps the neurodegenerative disease common in the elderly, offering the most immediate intuitive parallels with RLS is parkinsonism. Both conditions are related to dopamine system dysfunction. This leads to the prediction that RLS should be more likely to occur in parkinsonian conditions, such as idiopathic Parkinson’s disease, and related conditions, such as dementia with Lewy bodies and multiple system atrophy. Only one study to date has supported this hypothesis,70 and numerous other studies have shown mixed evidence71,72 or no relationship.7,9,33,73 One study reported that low serum ferritin levels may account for some RLS in parkinsonism,71 but another study has suggested that iron metabolism may be less of a factor in RLS with later onset.34 If RLS and parkinsonism are largely independent conditions, a more thorough understanding of their lack of overlap may be informative mechanistically. Because neuroimaging studies consistently have revealed presynaptic dysfunction in PD,74 the independence of RLS may suggest the importance of postsynaptic, purely functional, or predominantly diencephalospinal dysfunction in the latter condition.75 Features occasionally accompanying RLS, such as flexor reflex or sensory abnormalities, are consistent with dysfunction of dopaminergic efferents and afferents within the dorsal horn of the spinal cord that are atypical for parkinsonism.75 Neuroimaging (SPECT) visualizing the dopamine transporter in age-matched RLS and Parkinson’s disease patients indicated binding preservation in the RLS patients,76 also arguing for the independence of the two conditions. Finally, a post-mortem series of RLS patients failed to demonstrate Lewy bodies or alpha-synuclein deposits, which represent defining features of all forms of parkinsonism.77

Treatment Considerations for the Dementia Patient

In the dementia patient who wanders with corroborative informant history of RLS and/or a medical comorbidity related to RLS, there is no reason to suspect that an empirical trial of a low-dose dopaminergic agonist (0.25 to 1.0 mg ropinirole; 0.125 to 0.25 mg pramipexole) could not be used. The clinician, however, must bear in mind that because of possible dopamine-induced psychosis in a potentially vulnerable patient population, rapid dose escalation of such medications is ill advised, even if such an approach might be considered for the cognitively intact adult patient. A reasonable first step would be to consider carefully all ongoing medications to determine the potential of any of these to exacerbate RLS, before implementing any new treatment regimen. Studies in nondemented populations showing that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors6,28 and antidepressants such as venlafaxine28 and mirtazapine78,79 can be associated with PLMS and/or RLS would certainly suggest that these medications be discontinued as an initial intervention, although one recent study presented conflicting data.80 Perhaps even more relevant for the dementia population are several case reports suggesting that atypical antipsychotics (olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone) that exert partial blockade at specific dopaminergic receptors (e.g., olanzapine at D1-D4, quetiapine at D1/D2, risperidone at D2) may aggravate RLS or PLMS.81–83 Such medications are often used to decrease nocturnal agitation (including wandering) in dementia patients, and, curiously, at least one case series reported successful treatment of nocturnal wandering in AD patients84 using risperidone. Nonetheless, neuroleptic use was a risk factor for RLS in population-based studies of nondemented populations,7,10 and such medication would be hypothesized only to aggravate, rather than improve, wandering behavior in a demented patient. Some perspective on this was also offered by secondary analyses from a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of risperidone in dementia.85 In those analyses, wandering at baseline predicted higher rates of falls at 2.0 mg/day but appeared protective at 1.0 mg. Because this study was not specifically focused on identification of RLS, it remains unclear whether any of these patients might have met National Institutes of Health Workshop Guidelines criteria for RLS, although that is certainly possible. Additional possibly relevant data derive from a study of normal adults administered quetiapine (25 mg and 100 mg).86 In that study, both dosages improved polysomnographically defined sleep architecture, but PLMS increased under 100 mg. When viewed in aggregate, these studies imply that use of atypical antipsychotics for wandering in the dementia patient (itself constituting an off-label use) should be entertained only after full consideration of a premorbid likelihood of RLS. Indeed, a recent meta-analysis87 has suggested that sudden cardiac death is as possible with the atypical antipsychotics as with older-generation antipsychotics,88 which also exert dopaminergic blockade. Thus, judicious use of these medications in the wandering dementia patient is indicated.

1. Allen RP, Picchietti D, Hening WA, et al. Restless legs syndrome: Diagnostic criteria, special considerations, and epidemiology. A report from the restless legs syndrome diagnosis and epidemiology workshop at the National Institutes of Health. Sleep Med. 2003;4:101-119.

2. Bjorvatn B, Leissner L, Ulfberg J, et al. Prevalence, severity and risk factors of restless legs syndrome in the general adult population in two Scandinavian countries. Sleep Med. 2005;6:307-312.

3. Ulfberg J, Nystrom B, Carter N, et al. Prevalence of restless legs syndrome among men aged 18 to 64 years: An association with somatic disease and neuropsychiatric symptoms. Mov Disord. 2001;16:1159-1163.

4. Lavigne GJ, Montplaisir JY. Restless legs syndrome and sleep bruxism: Prevalence and association among Canadians. Sleep. 1994;17:739-743.

5. Phillips B, Young T, Finn L, et al. Epidemiology of restless legs symptoms in adults. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2137-2141.

6. Ohayon MM, Roth T. Prevalence of restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder in the general population. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:547-554.

7. Van De, Vijver DA, Walley T, et al. Epidemiology of restless legs syndrome as diagnosed in UK primary care. Sleep Med. 2004;5:435-440.

8. Tison F, Crochard A, Leger D, et al. Epidemiology of restless legs syndrome in French adults: A nationwide survey: The INSTANT Study. Neurology. 2005;65:239-246.

9. Wenning GK, Kiechl S, Seppi K, et al. Prevalence of movement disorders in men and women aged 50-89 years (Bruneck Study cohort): A population-based study. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4:815-820.

10. Rothdach AJ, Trenkwalder C, Haberstock J, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of RLS in an elderly population: The MEMO study. Memory and Morbidity in Augsburg Elderly. Neurology. 2000;54:1064-1068.

11. Nichols DA, Allen RP, Grauke JH, et al. Restless legs syndrome symptoms in primary care: A prevalence study. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2323-2329.

12. Berger K, Luedemann J, Trenkwalder C, et al. Sex and the risk of restless legs syndrome in the general population. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:196-202.

13. Allen RP, Walters AS, Montplaisir J, et al. Restless legs syndrome prevalence and impact: REST general population study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1286-1292.

14. Hogl B, Kiechl S, Willeit J, et al. Restless legs syndrome: A community-based study of prevalence, severity, and risk factors. Neurology. 2005;64:1920-1924.

15. Tan EK, Seah A, See SJ, et al. Restless legs syndrome in an Asian population: A study in Singapore. Mov Disord. 2001;16:577-579.

16. Mizuno S, Miyaoka T, Inagaki T, et al. Prevalence of restless legs syndrome in non-institutionalized Japanese elderly. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59:461-465.

17. Sevim S, Dogu O, Camdeviren H, et al. Unexpectedly low prevalence and unusual characteristics of RLS in Mersin, Turkey. Neurology. 2003;61:1562-1569.

18. Kim J, Choi C, Shin K, et al. Prevalence of restless legs syndrome and associated factors in the Korean adult population: The Korean Health and Genome Study. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59:350-353.

19. Rijsman R, Neven AK, Graffelman W, et al. Epidemiology of restless legs in the Netherlands. Eur J Neurol. 2004;11:607-611.

20. Kageyama T, Kabuto M, Nitta H, et al. Prevalences of periodic limb movement-like and restless legs-like symptoms among Japanese adults. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;54:296-298.

21. Brody JA, Schneider EL. Diseases and disorders of aging: An hypothesis. J Chronic Dis. 1986;39:871-876.

22. Phillips B, Hening W, Britz P, et al. Prevalence and correlates of restless legs syndrome: Results from the 2005 National Sleep Foundation Poll. Chest. 2006;129:76-80.

23. Mold JW, Vesely SK, Keyl BA, et al. The prevalence, predictors, and consequences of peripheral sensory neuropathy in older patients. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2004;17:309-318.

24. Mold JW, Roberts M, Aboshady HM. Prevalence and predictors of night sweats, day sweats, and hot flashes in older primary care patients: An OKPRN study. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2:391-397.

25. Picchietti D, Winkelman JW. Restless legs syndrome, periodic limb movements in sleep, and depression. Sleep. 2005;28:891-898.

26. Sukegawa T, Itoga M, Seno H, et al. Sleep disturbances and depression in the elderly in Japan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003;57:265-270.

27. Hornyak M, Kopasz M, Berger M, et al. Impact of sleep-related complaints on depressive symptoms in patients with restless legs syndrome. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:1139-1145.

28. Yang C, White DP, Winkelman JW. Antidepressants and periodic leg movements of sleep. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:510-514.

29. O’Keeffe ST, Gavin K, Lavan JN. Iron status and restless legs syndrome in the elderly. Age Ageing. 1994;23:200-203.

30. Earley CJ, Connor JR, Beard JL, et al. Abnormalities in CSF concentrations of ferritin and transferrin in restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 2000;54:1698-1700.

31. Allen RP, Barker PB, Wehrl F, et al. MRI measurement of brain iron in patients with restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 2001;56:263-265.

32. O’Keeffe ST. Secondary causes of restless legs syndrome in older people. Age Ageing. 2005;34:349-352.

33. Berger K, von Eckardstein A, Trenkwalder C, et al. Iron metabolism and the risk of restless legs syndrome in an elderly general population—The MEMO-Study. J Neurol. 2002;249:1195-1199.

34. Earley CJ, Connor JR, Beard JL, et al. Ferritin levels in the cerebrospinal fluid and restless legs syndrome: Effects of different clinical phenotypes. Sleep. 2005;28:1069-1075.

35. Ancoli-Israel S, Kripke DF, Klauber MR, et al. Periodic limb movements in sleep in community-dwelling elderly. Sleep. 1991;14:496-500.

36. Youngstedt SD, Kripke DF, Klauber MR, et al. Periodic leg movements during sleep and sleep disturbances in elders. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1998;53:M391-394.

37. Bixler EO, Kales A, Vela-Bueno A, et al. Nocturnal myoclonus and nocturnal myoclonic activity in the normal population. Res Commun Chem Pathol Pharmacol. 1982;36:129-140.

38. Kales A, Bixler EO, Soldatos CR, et al. Biopsychobehavioral correlates of insomnia, part 1: Role of sleep apnea and nocturnal myoclonus. Psychosomatics. 1982;23:589-600.

39. Mosko SS, Dickel MJ, Paul T, et al. Sleep apnea and sleep-related periodic leg movements in community resident seniors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1988;36:502-508.

40. Bliwise D, Petta D, Seidel W, et al. Periodic leg movements during sleep in the elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 1985;4:273-281.

41. Youngstedt SD, Kripke DF, Elliott JA, et al. Circadian abnormalities in older adults. J Pineal Res. 2001;31:264-272.

42. Mendelson WB. Are periodic leg movements associated with clinical sleep disturbance? Sleep. 1996;19:219-223.

43. Montplaisir J, Michaud M, Denesle R, et al. Periodic leg movements are not more prevalent in insomnia or hypersomnia but are specifically associated with sleep disorders involving a dopaminergic impairment. Sleep Med. 2000;1:163-167.

44. Karadeniz D, Ondze B, Besset A, et al. Are periodic leg movements during sleep (PLMS) responsible for sleep disruption in insomnia patients? Eur J Neurol. 2000;7:331-336.

45. Hornyak M, Trenkwalder C. Restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder in the elderly. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56:543-548.

46. Carrier J, Frenette S, Montplaisir J, et al. Effects of periodic leg movements during sleep in middle-aged subjects without sleep complaints. Mov Disord. 2005;20:1127-1132.

47. Bliwise DL, Carskadon MA, Dement WC. Nightly variation of periodic leg movements in sleep in middle aged and elderly individuals. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 1988;7:273-279.

48. Edinger JD, McCall WV, Marsh GR, et al. Periodic limb movement variability in older DIMS patients across consecutive nights of home monitoring. Sleep. 1992;15:156-161.

49. Mosko SS, Dickel MJ, Ashurst J. Night-to-night variability in sleep apnea and sleep-related periodic leg movements in the elderly. Sleep. 1988;11:340-348.

50. Coleman RM, Miles LE, Guilleminault CC, et al. Sleep-wake disorders in the elderly: polysomnographic analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1981;29:289-296.

51. Pennestri MH, Whittom S, Adam B, et al. PLMS and PLMW in healthy subjects as a function of age: Prevalence and interval distribution. Sleep. 2006;29:1183-1187.

52. Gosselin N, Lanfranchi P, Michaud M, et al. Age and gender effects on heart rate activation associated with periodic leg movements in patients with restless legs syndrome. Clin Neurophysiol. 2003;114:2188-2195.

53. Algase DL. Wandering in dementia. Annu Rev Nurs Res. 1999;17:185-217.

54. Silverstein NM, Flaherty G, Tobin TS. Dementia and Wandering Behavior: Concern for the Lost Elder. New York: Springer Publishing Company, 2002.

55. Logsdon RG, Teri L, McCurry SM, et al. Wandering: A significant problem among community-residing individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1998;53:P294-299.

56. Rowe MA, Glover JC. Antecedents, descriptions and consequences of wandering in cognitively-impaired adults and the Safe Return (SR) program. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2001;16:344-352.

57. Tractenberg RE, Singer CM, Cummings JL, et al. The Sleep Disorders Inventory: An instrument for studies of sleep disturbance in persons with Alzheimer’s disease. J Sleep Res. 2003;12:331-337.

58. Snyder LH, Rupprecht P, Pyrek J, et al. Wandering. Gerontologist. 1978;18:272-280.

59. Nasman B, Bucht G, Eriksson S, et al. Behavioural symptoms in the institutionalized elderly: relationship to dementia. Int J Geriatr Psych. 1993;8:843-849.

60. Kavcic V, Duffy CJ. Attentional dynamics and visual perception: Mechanisms of spatial disorientation in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2003;126(Pt 5):1173-1181.

61. Tetewsky SJ, Duffy CJ. Visual loss and getting lost in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1999;52:958-965.

62. Meguro K, Yamaguchi S, Itoh M, et al. Striatal dopamine metabolism correlated with frontotemporal glucose utilization in Alzheimer’s disease: A double-tracer PET study. Neurology. 1997;49:941-945.

63. Tanaka Y, Meguro K, Yamaguchi S, et al. Decreased striatal D2 receptor density associated with severe behavioral abnormality in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Nucl Med. 2003;17:567-573.

64. Rolland Y, Payoux P, Lauwers-Cances V, et al. A SPECT study of wandering behavior in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20:816-820.

65. Turjanski N, Lees AJ, Brooks DJ. Striatal dopaminergic function in restless legs syndrome: 18F-dopa and 11C-raclopride PET studies. Neurology. 1999;52:932-937.

66. Garcia-Borreguero D, Odin P, Serrano C. Restless legs syndrome and PD: A review of the evidence for a possible association. Neurology. 2003;61(6 suppl 3):S49-S55.

67. Martino-Saltzman D, Blasch BB, Morris RD, et al. Travel behavior of nursing home residents perceived as wanderers and nonwanderers. Gerontologist. 1991;31:666-672.

68. Tractenberg RE, Singer CM, Kaye JA. Characterizing sleep problems in persons with Alzheimer’s disease and normal elderly. J Sleep Res. 2006;15:97-103.

69. Pearson VE, Allen RP, Dean T, et al. Cognitive deficits associated with restless legs syndrome (RLS). Sleep Med. 2006;7:25-30.

70. Krishnan PR, Bhatia M, Behari M. Restless legs syndrome in Parkinson’s disease: A case-controlled study. Mov Disord. 2003;18:181-185.

71. Ondo WG, Vuong KD, Jankovic J. Exploring the relationship between Parkinson disease and restless legs syndrome. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:421-424.

72. Nomura T, Inoue Y, Miyake M, et al. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of restless legs syndrome in Japanese patients with Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2005;250:39-44.

73. Tan EK, Lum SY, Wong MC. Restless legs syndrome in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Sci. 2002;196:33-36.

74. Micheli F, Cersosimo MG, Wooten GF. Neurochemistry and neuropharmacology of Parkinson’s disease. In: Watts RL, Koeller WC, editors. Movement Disorders: Neurologic Principles and Practice. 2. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2004:197-207.

75. Rye DB. Parkinson’s disease and RLS: The dopaminergic bridge. Sleep Med. 2004;5:317-328.

76. Linke R, Eisensehr I, Wetter TC, et al. Presynaptic dopaminergic function in patients with restless legs syndrome: Are there common features with early Parkinson’s disease? Mov Disord. 2004;19:1158-1162.

77. Pittock SJ, Parrett T, Adler CH, et al. Neuropathology of primary restless leg syndrome: Absence of specific tau- and alpha-synuclein pathology. Mov Disord. 2004;19:695-699.

78. Agargun MY, Kara H, Ozbek H, et al. Restless legs syndrome induced by mirtazapine. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:1179.

79. Bahk WM, Pae CU, Chae JH, et al. Mirtazapine may have the propensity for developing a restless legs syndrome? A case report. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2002;56:209-210.

80. Brown LK, Dedrick DL, Doggett JW, et al. Antidepressant medication use and restless legs syndrome in patients presenting with insomnia. Sleep Med. 2005;6:443-450.

81. Pinninti NR, Mago R, Townsend J, et al. Periodic restless legs syndrome associated with quetiapine use: A case report. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;25:617-618.

82. Kraus T, Schuld A, Pollmacher T. Periodic leg movements in sleep and restless legs syndrome probably caused by olanzapine. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;19:478-479.

83. Wetter TC, Brunner J, Bronisch T. Restless legs syndrome probably induced by risperidone treatment. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2002;35:109-111.

84. Meguro K, Meguro M, Tanaka Y, et al. Risperidone is effective for wandering and disturbed sleep/wake patterns in Alzheimer’s disease. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2004;17:61-67.

85. Katz IR, Rupnow M, Kozma C, et al. Risperidone and falls in ambulatory nursing home residents with dementia and psychosis or agitation: Secondary analysis of a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;12:499-508.

86. Cohrs S, Rodenbeck A, Guan Z, et al. Sleep-promoting properties of quetiapine in healthy subjects. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2004;174:421-429.

87. Schneider LS, Dagerman KS, Insel P. Risk of death with atypical antipsychotic drug treatment for dementia: Meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. JAMA. 2005;294:1934-1943.

88. Ray WA, Meredith S, Thapa PB, et al. Antipsychotics and the risk of sudden cardiac death. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:1161-1167.