Chapter 22 Restless Legs Syndrome and Periodic Limb Movement Disorder in Childhood and Adolescence

Until recently, restless legs syndrome (RLS) was generally believed to be a disorder of adults. However, multiple reports now document the occurrence of RLS, as well as the related problem of periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD), during childhood and adolescence.1–9 A recent population-based epidemiological study found an RLS prevalence of 2% in children ages 8 to 17 years.10 PLMD has been reported in 8.4% of children in a clinic-referred sample.11 Symptoms can range from mild to severe and in many cases can have a significant impact on a child’s quality of life.10 Thus, RLS and PLMD represent relatively common, medically significant pediatric disorders that are often not diagnosed. Advances in the understanding and treatment of these disorders permit an accurate diagnosis and effective treatment.

Symptoms of Restless Legs Syndrome

Like adults, children with RLS seek relief of discomfort by moving their legs, fidgeting, stretching, walking, running, rocking, or changing positions. In the classroom, this may be viewed as inattentiveness, hyperactivity, or disruptive behavior. The RLS discomfort is typically described with age-appropriate but nonspecific terms such as “oowies,” “boo-boos,” “tickle,” “bugs,” “spiders,” “ants,” “static,” and “a lot of energy in my legs.” Sleep disturbance is common in both children and adults with RLS. In some children, the sleep disturbance may precede or overshadow the complaint of typical RLS leg discomfort.9,12 Often, sleep quantity and quality are affected with resultant consequences on daytime function.

Periodic Limb Movement Disorder

Periodic limb movements in sleep (PLMS) are characterized by brief jerks during sleep (lasting 0.5 to 5.0 seconds), which typically occur at 20- to 40-second intervals.13,14 PLMS are more common in the toes, feet, and legs, than in the arms. The affected individual is usually not aware of the movements or of the associated transient arousals that disrupt sleep continuity. Between 80% and 90% of adults with RLS have PLMS.15 In healthy children and even young adults, PLMS rarely exceed five per hour.16–18 Thus, the presence of PLMS of more than five per hour in children or adolescents supports a diagnosis of RLS (see later).19 PLMS, however, are not specific to RLS but also can be seen in some other sleep disorders and can be induced or aggravated by certain medications (particularly antidepressant medications).14,20 PLMD is diagnosed when there are (1) PLMS exceeding norms for age (>5 per hour for children), (2) clinical sleep disturbance, and (3) the absence of another primary sleep disorder or reason for the PLMS.14 In some children, a diagnosis of PLMD will evolve over time to a diagnosis of “RLS with PLMS” as the typical RLS feelings develop.

Diagnostic Criteria

Special criteria for the diagnosis of RLS were established for children at a National Institutes of Health (NIH) consensus conference on RLS.19 These criteria for childhood RLS should be used up to and including the age of 12 years, after which the adult criteria should be used. Several issues led to the development of separate criteria, which include (1) young children may have difficulty in describing the RLS feelings, (2) clinical experience indicates that children may report the RLS discomfort more during the day than at night or may not be able to determine when it is worse, and (3) a family history of RLS in a first-degree relative is likely relevant if a child meets some, but not all, of the adult criteria for RLS. However, the criteria for definite RLS were constructed as more difficult to fulfill than the criteria for adults because of a desire that false-positive diagnoses be avoided. Children can be diagnosed with definite RLS in either of two ways, as described in the table below (Table 22-1). Criteria for probable RLS and possible RLS were developed for research purposes (Tables 22-2 and 22-3).

TABLE 22-1 Criteria for the Diagnosis of Definite RLS in Children

| Child meets all four of the following adult criteria: |

| • An urge to move the legs |

| • The urge to move begins or worsens when sitting or lying down |

| • The urge to move is partially or totally relieved by movement |

| • The urge to move is worse in the evening or night than during the day or only occurs in the evening or night |

| And |

| The child uses his or her own words to describe leg discomfort. |

| Examples of age-appropriate descriptors: oowies, tickle, tingle, static, bugs, spiders, ants, boo-boos, want to run, and a lot of energy in my legs. |

| OR |

| Child meets all four of the above adult criteria |

| And |

| Two or three of the following supportive criteria: |

| • Sleep disturbance for age |

| • Biological parent or sibling has definite RLS |

| • The child has a sleep study documenting a periodic limb movement index of 5 or more per hour of sleep |

TABLE 22-2 Criteria for the Diagnosis of Probable RLS in Children

| The child meets all essential adult criteria for RLS, except criterion #4 (the urge to move or sensations are worse in the evening or at night than during the day) |

| And |

| The child has a biological parent or sibling with definite RLS |

| OR |

| The child is observed to have behavior manifestations of lower-extremity discomfort when sitting or lying down, with motor movement of the affected limbs. The discomfort has characteristics of adult criteria 2, 3, & 4: worse during rest and inactivity, relieved by movement, and worse during the evening and night. |

| And |

| The child has a biological parent or sibling with definite RLS |

TABLE 22-3 Criteria for the Diagnosis for Possible RLS in Children

| The child has periodic limb movement disorder |

| And |

| The child has a biological parent or sibling with definite RLS, but the child does not meet definite or probable childhood RLS definitions. |

Source: The NIH RLS workshop. RLS: Diagnosis and Diagnostic and Epidemiological Tools (2003).19

Prevalence, Impact, and Relationship to “Growing Pains”

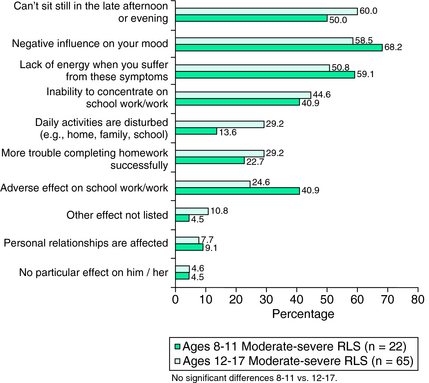

A large epidemiological study applied the NIH workshop diagnostic criteria to a population-based questionnaire survey of families with children in the United States and the United Kingdom.10 Definite RLS criteria were met by 1.9% and 2% of all children ages 8 to 11 and 12 to 17 years, respectively. RLS occurring = 2/week and causing moderate to severe distress when present had been identified by a panel of experts as indicating clinically significant RLS for adults, likely to benefit from treatment.21,22 In the pediatric study, 0.5% of children ages 8 to 11 years and 1.0% of those ages 12 to 17 years reported symptoms meeting these criteria for clinically significant RLS. There were no significant gender differences. A family history of RLS was common, with 70% of all children diagnosed with definite RLS having a biological parent who reported symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of RLS, including 16% for whom both parents had RLS symptoms. The children with definite RLS symptoms, compared with the non-RLS children, more commonly reported sleep disturbance (69% versus 40%, p <.001). In addition, children with clinically significant RLS reported a high rate of adverse consequences from the RLS symptoms, such as negative mood (59% to 68%), decreased energy (51% to 59%), and inability to concentrate on school work (41% to 45%) (Fig. 21-1).

Six other studies have reported pediatric-onset RLS prevalence data and one has reported pediatric PLMD prevalence data. A study of 1084 unselected children from 12 pediatric practices found RLS to affect 1.3%.23 At a pediatric sleep disorders center, 32 of 538 children (5.9%) received a diagnosis of RLS.9 Twenty-three (4.2%) of these were found to have definite RLS and 9 (1.7%) were found to have probable RLS by the NIH consensus criteria for children.19 Another study that included a question about “leg restlessness at bedtime” found this in 6.1% of Canadian children ages 11 to 13 years.24 Retrospective recall of RLS symptoms has been reported in three adult RLS studies, with onset before age 20 found in 27% to 38% and before age 10 in 8% to 13%.15,25,26 In the majority of cases, symptoms were reported as mild in childhood and medical attention was not usually sought, but in one series where some children did seek medical attention, “growing pains” was a frequent misdiagnosis.25 Polysomnographically confirmed PLMD was found in 8.4% of a clinic-referred sample and in 11.9% of children recruited from the community.11

A review of the “growing pain” literature indicates that some children with “growing pains” meet criteria for RLS.27 There have also been recent reports of children who were misdiagnosed as having “growing pains” but who met the criteria for RLS.8 Ekbom28 thought that RLS could be misdiagnosed as “growing pains,” but based on a limited number of cases, he concluded that the “growing pain” leg sensations retrospectively recalled by adult RLS were different in character than the RLS leg sensations they currently experienced as adults. Brenning,29 a contemporary of Ekbom, took a somewhat different view and elicited evidence suggesting a close connection between “growing pains” and RLS. First, he showed that adults with RLS-like symptoms are much more likely to have experienced “growing pains” as children than adult controls. Second, he showed that the parents of children with “growing pains” are more likely to have experienced “growing pains” as children than the parents of control children. His third important observation was that in the parents of children with “growing pains,” RLS-like features in adulthood occur far more frequently than in control parents. These latter observations are of potential interest given the familial, presumably autosomal dominant nature of early-onset RLS.30 The weakness of Brenning’s observations was that he included patients with conditions other than RLS in his study. In the large pediatric epidemiologic study of RLS, growing pains were, as expected, reported more commonly for those with RLS symptoms than others (81% versus 63%, p <.001).10

Relationship to Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

Literature has focused on the possible relationship between RLS, PLMD, or both to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). The initial interest in this area came about as a result of studies suggesting a possible link between ADHD and sleep deprivation,31 as well as disorders such as obstructive sleep apnea32 and narcolepsy.33 The theory is that poor sleep can induce or aggravate symptoms of ADHD. The pediatric epidemiologic study of RLS showed that children in the United States with RLS symptoms had very high rates of medically diagnosed ADHD (27%).10

In two different series, between 26% and 64% of children with ADHD had PLMS of greater than five per hour of sleep.4,5 The first of these series studied 69 ADHD patients and found 8 of 18 children with ADHD and PLMS greater than five per hour of sleep had both a personal and parental history of RLS (44.4%).4 In the second of these series, 8 of 25 parents of the children with ADHD (32%) had symptoms of RLS as opposed to none of the control parents.5 In that same study, 6 of the 9 children who had both ADHD and PLMS greater than five per hour of sleep had a parent with RLS (67%). These data overall suggest a possible link between RLS/PLMS and ADHD. A video analysis of patients with ADHD revealed that they move around much more in sleep compared with control subjects.34 In a large community-based cross-sectional survey of 866 children, symptoms of ADHD as measured by objective indices were almost twice as likely to occur with symptoms of RLS than would be expected by chance alone.7 In a survey, 44% of ADHD children with a mean age of 9.2 years met criteria for RLS.35 In a polysomnographic study of 113 children, those who had a combination of ADHD symptoms, sleep-disordered breathing (SDB), and PLMS, it was only the PLMS that showed a linear relationship to ADHD symptoms.36 However, the linearity was present in children who had ADHD, PLMS, and SDB but not in those who did not have SDB. Based on these results, Chervin and colleagues36 have suggested that SDB acts as a modifier to the more intimate relationship between PLMS and ADHD.36 Golan and coworkers37 found 15% of ADHD children to have PLMD, compared with 0% of control subjects (p =.05).

Not only do children with ADHD have more PLMS, but also children with PLMS have a greater incidence of ADHD. Approximately 44% of children with PLMS greater than five per hour have been found to have symptoms of ADHD.11 The reverse prevalence also seems to hold for RLS and the link between RLS and ADHD may persist into adulthood. Sixty-two adults with RLS more frequently had symptoms suggestive of ADHD than 77 normal adult controls (26% versus 5%).38 In this study, the severity of RLS was greater in RLS patients with ADHD than in those without ADHD as determined by the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group rating scale for RLS.39,40 Other behavioral problems, such as conduct disorder, also seem to be highly associated with RLS/PLMS.41

Treatment

Treatment studies in childhood RLS are in their infancy and only open-label studies are available. These studies are confined to the dopaminergic agents, gabapentin, clonazepam, and iron therapy, although there is unpublished clinical experience from the practices of both Walters and Picchietti that clonidine may be helpful in childhood RLS.

It is well known that iron deficiency is an important factor in adult RLS, probably because of iron’s vital role in dopamine function.42 This may also be true of childhood RLS. Studies in children and adults have shown increased frequency of RLS and PLMS associated with serum ferritin concentrations below 35 to 50 µg/L.43–47 One of these was a prospective study that examined 39 children with an average age of 7.5 years who had PLMS greater than five per hour of sleep.45 Low serum iron levels were significantly correlated with a higher PLMS index, and iron therapy over 3 months resulted in a reduction of the PLMS index from 27.6 per hour to 12.6 per hour (p <.001). Of interest is recent work that found low serum ferritin levels correlated with ADHD severity in 43 children with ADHD, of whom 44% met criteria for RLS.35,48

In one study, dopaminergic agents improved not only the RLS/PLMS symptoms but also the ADHD symptoms in children with both RLS/PLMS and ADHD (age range, 6 to 14 years).49 This further supports a link between RLS/PLMS and ADHD. Dosage range was carbidopa/levodop. 75/150 CR to 150/300 CR per day for five children or pergolide 0.4 to 1 mg per day for two children. There was an improvement in RLS leg discomfort and a statistically significant decrement in the PLMS index and associated arousals. The PLMS index fell from 11.7 to 2.1 per hour of sleep (p =.018), and the total number of PLMS associated arousals/night fell from 21.4 to 1.8 (p =.042). Because the clinicians were also treating daytime ADHD symptoms, dosing was usually 3 or 4 times daily. In a study of 10 children with RLS originally misdiagnosed as having growing pains (mean age, 10.4 years), four were treated with one tablet of carbidopa/levodopa 25/100 CR before bedtime.8 Symptomatic improvement in the IRLS rating scale for RLS severity was found in three patients. The scores decreased from 30, 28, and 33 to 15, 12, and 10, respectively. Note that because the authors were only treating nighttime RLS symptoms, dosages were lower than those in the aforementioned study. Ropinirole has been reported in one child to have resulted in significant improvement of RLS, ADHD, and sleep symptoms.50 Guilleminault and colleagues51 treated two children with RLS/PLMS and confusional arousals (sleepwalking or sleep terrors) with the use of pramipexole. The PLMS arousal index decreased from 11 and 16 to 0 and 0.2, respectively. The confusional arousals resolved with pramipexole treatment as well, suggesting that RLS/PLMS triggered the confusional arousals. In addition, pramipexole, gabapentin, and clonazepam given individually have been reported as beneficial in a pediatric RLS case series, and pramipexole, in a PLMS case series.9,52

1. Walters AS, Picchietti DL, Ehrenberg BL, et al. Restless legs syndrome in childhood and adolescence. Pediatr Neurol. 1994;11:241-245.

2. Wilson VN, Buchholz D, Walters AS. Sleep Thief, Restless Legs Syndrome. Orange Park, FL: Galaxy Books, 1996.

3. Picchietti DL, Walters AS. Restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder in children and adolescents: Comorbidity with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Child Adolesc Psych Clin N Am. 1996;5:729-740.

4. Picchietti DL, England SJ, Walters AS, et al. Periodic limb movement disorder and restless legs syndrome in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Child Neurol. 1998;13:588-594.

5. Picchietti DL, Underwood DJ, Farris WA, et al. Further studies on periodic limb movement disorder and restless legs syndrome in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Mov Disord. 1999;14:1000-1007.

6. Picchietti DL, Walters AS. Moderate to severe periodic limb movement disorder in childhood and adolescence. Sleep. 1999;22:297-300.

7. Chervin RD, Archbold KH, Dillon JE, et al. Associations between symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, restless legs, and periodic leg movements. Sleep. 2002;25:213-218.

8. Rajaram SS, Walters AS, England SJ, et al. Some children with growing pains may actually have restless legs syndrome. Sleep. 2004;27:767-773.

9. Kotagal S, Silber MH. Childhood-onset restless legs syndrome. Ann Neurol. 2004;56:803-807.

10. Picchietti D, Allen RP, Walters AS, et al. Restless legs syndrome: prevalence and impact in children and adolescents—The Peds REST study. Pediatrics. 2007;120:253-266.

11. Crabtree VM, Ivanenko A, O’Brien LM, Gozal D. Periodic limb movement disorder of sleep in children. J Sleep Res. 2003;12:73-81.

12. Picchietti D, Stevens HE. Early manifestations of restless legs syndrome in childhood [abstract]. Sleep. 2005;28:A74.

13. The Atlas Task Force. Recording and scoring leg movements. Sleep. 1993;16:748-759.

14. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders. Diagnostic And Coding Manual, Second. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 2005.

15. Montplaisir J, Boucher S, Poirier G, et al. Clinical, polysomnographic, and genetic characteristics of restless legs syndrome: A study of 133 patients diagnosed with new standard criteria. Mov Disord. 1997;12:61-65.

16. Pennestri MH, Whittom S, Adam B, et al. PLMS and PLMW in healthy subjects as a function of age: Prevalence and interval distribution. Sleep. 2006;29:1183-1187.

17. Montgomery-Downs HE, O’Brien LM, et al. Polysomnographic characteristics in normal preschool and early school-aged children. Pediatrics. 2006;117:741-753.

18. Traeger N, Schultz B, Pollock AN, et al. Polysomnographic values in children 2-9 years old: Additional data and review of the literature. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2005;40:22-30.

19. Allen RP, Picchietti D, Hening WA, et al. Restless legs syndrome: Diagnostic criteria, special considerations, and epidemiology. A report from the Restless Legs Syndrome Diagnosis and Epidemiology Workshop at the National Institutes of Health. Sleep Med. 2003;4:101-119.

20. Picchietti D, Winkelmann JW. Restless legs syndrome, periodic limb movements in sleep, and depression. Sleep. 2005;28:891-898.

21. Allen RP, Walters AS, Montplaisir J, et al. Restless legs syndrome prevalence and impact: REST general population study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1286-1292.

22. Hening W, Walters AS, Allen RP, et al. Impact, diagnosis and treatment of restless legs syndrome (RLS) in a primary care population: The REST (RLS epidemiology, symptoms, and treatment) primary care study. Sleep Med. 2004;5:237-246.

23. Kinkelbur J, Hellwig J, Hellwig M. Frequency of RLS symptoms in childhood. Somnologie. 2003;7(suppl 1):34.

24. Laberge L, Tremblay RE, Vitaro F, et al. Development of parasomnias from childhood to early adolescence. Pediatrics. 2000;106:67-74.

25. Walters AS, Hickey K, Maltzman J, et al. A questionnaire study of 138 patients with restless legs syndrome: The ‘Night-Walkers’ survey. Neurology. 1996;46:92-95.

26. Bassetti CL, Mauerhofer D, Gugger M, et al. Restless legs syndrome: A clinical study of 55 patients. Eur Neurol. 2001;45:67-74.

27. Walters AS. Is there a subpopulation of children with growing pains who really have restless legs syndrome? A review of the literature. Sleep Med. 2002;3:93-98.

28. Ekbom KA. Growing pains and restless legs. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1975;64:264-266.

29. Brenning R. Growing pains. Acta Soc Med Upsalien. 1960;65:185-201.

30. Winkelmann J, Muller-Myhsok B, Wittchen HU, et al. Complex segregation analysis of restless legs syndrome provides evidence for an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance in early age at onset families. Ann Neurol. 2002;52:297-302.

31. Dahl RE. The impact of inadequate sleep on children’s daytime cognitive function. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 1996;3:44-50.

32. Guilleminault C, Korobkin R, Winkle R. A review of 50 children with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Lung. 1981;159:275-287.

33. Weinberg WA, Emslie GJ. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: the differential diagnosis. J Child Neurol. 1991;6(suppl):S23-S36.

34. Konofal E, Lecendreux M, Bouvard MP, et al. High levels of nocturnal activity in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A video analysis. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2001;55:97-103.

35. Konofal E, Lecendreux M, Arnulf I, et al. Restless legs syndrome and serum ferritin levels in ADHD children [abstract]. Sleep. 2003;26:136.

36. Chervin RD, Archbold KH. Hyperactivity and polysomnographic findings in children evaluated for sleep-disordered breathing. Sleep. 2001;24:313-320.

37. Golan N, Shahar E, Ravid S, et al. Sleep disorders and daytime sleepiness in children with attention-deficit/hyperactive disorder. Sleep. 2004;27:261-266.

38. Wagner ML, Walters AS, Fisher BC. Symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults with restless legs syndrome. Sleep. 2004;27:1499-1504.

39. Walters AS, LeBrocq C, Dhar A, et al. Validation of the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group rating scale for restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2003;4:121-132.

40. Hening WA, Allen RP. Restless legs syndrome (RLS): The continuing development of diagnostic standards and severity measures. Sleep Med. 2003;4:95-97.

41. Chervin RD, Dillon JE, Archbold KH, et al. Conduct problems and symptoms of sleep disorders in children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42:201-208.

42. Allen R. Dopamine and iron in the pathophysiology of restless legs syndrome (RLS). Sleep Med. 2004;5:385-391.

43. Kryger MH, Otake K, Foerster J. Low body stores of iron and restless legs syndrome: A correctable cause of insomnia in adolescents and teenagers. Sleep Med. 2002;3:127-132.

44. O’Keeffe ST, Gavin K, Lavan JN. Iron status and restless legs syndrome in the elderly. Age Ageing. 1994;23:200-203.

45. Simakajornboon N, Gozal D, Vlasic V, et al. Periodic limb movements in sleep and iron status in children. Sleep. 2003;26:735-738.

46. Beard JL. Iron status and periodic limb movements of sleep in children: A causal relationship? Sleep Med. 2004;5:89-90.

47. Sun ER, Chen CA, Ho G, et al. Iron and the restless legs syndrome. Sleep. 1998;21:371-377.

48. Konofal E, Lecendreux M, Arnulf I, et al. Iron deficiency in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:1113-1115.

49. Walters AS, Mandelbaum DE, Lewin DS, et al. Dopaminergic therapy in children with restless legs/periodic limb movements in sleep and ADHD. Dopaminergic Therapy Study Group. Pediatr Neurol. 2000;22:182-186.

50. Konofal E, Arnulf I, Lecendreux M, et al. Ropinirole in a child with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and restless legs syndrome. Pediatr Neurol. 2005;32:350-351.

51. Guilleminault C, Palombini L, Pelayo R, et al. Sleepwalking and sleep terrors in prepubertal children: What triggers them? Pediatrics. 2003;111:e17-e25.

52. Martinez S, Guilleminault C. Periodic leg movements in prepubertal children with sleep disturbance. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2004;46:765-770.