Conflict Resolution in Emergency Medicine

• Conflict is the result of discordant expectations, goals, needs, agendas, communication styles, and backgrounds between individuals. At least two perspectives contribute to conflict.

• Conflict in emergency medicine may occur with patients, family members, nurses, consultants, residents, students, hospital administrative staff, or agents inside and outside the emergency department.

• The goals of effective conflict resolution are to optimize immediate outcomes and establish a solid foundation for subsequent interactions. Success depends on one’s communication style, awareness of other’s needs and psyche, and understanding of the dynamics of relationships.

• Successful conflict resolution requires a systematic and structured approach. It is important to recognize each participant’s principal interests and underlying positions. Having a strong best alternative to a negotiated agreement is beneficial. Possessing a “win-lose” attitude interferes with successful conflict resolution.

• Not all conflict in emergency medicine can be resolved immediately, if at all; some resolutions require the assistance of a neutral third party, such as a mediator. This is especially true for emotionally charged topics, differences in values, or differences occurring between individuals having unequal power.

• Efforts to prevent conflict before it happens are recommended whenever possible.

The problem with conflict is not its existence, but rather its management.1

Conflict is inevitable. Opportunities for conflict in emergency medicine (EM) are numerous because individuals with different backgrounds and divergent agendas interact over important concerns (e.g., patient care or resource utilization). By nature, these interactions take place under time constraints, which often exacerbates conflict. Many interactions between emergency physicians (EPs) and patients, family members, and staff or consultants occur with limited or no previous working relationship or when previous interactions have been problematic. As a result, the parties involved may be unable to reflect on previous successful interactions, which often decreases the likelihood of intense exchange.2

Controversy exists about the value of conflict. Many believe that at its best, conflict is disruptive. Most agree that at its worst, conflict is destructive to team harmony and patient outcomes. However, conflict also serves as a creative force by providing both initiative and incentive to solve problems.

This online version of the published chapter describes conflict in general and in detail, suggests many of its causes, and identifies contributing factors. Several examples of conflict specific to EM are discussed. The importance of effective communication in conflict resolution is presented, as well as its role in deescalating, minimizing, and preventing conflict. Recommendations for decreasing conflict are offered, and EPs are guided through the challenges of conflict resolution. The ultimate benefits to the patient, staff, and EP of resolving conflict are described, including optimizing patient care, decreasing patient morbidity, and maximizing an individual’s or health care team’s overall satisfaction. Finally, several strategies to facilitate conflict resolution are reviewed.

Communication, in the form of language and interaction, and power, in terms of how conflict is managed (or mismanaged), are tremendously important in the dynamics of groups. EM is very much about group dynamics because physicians, nurses, and other staff members must consistently demonstrate successful teamwork to offer patients the best possible outcomes. Louise B. Andrew, MD, JD, stated that “… conflict is often the result of miscommunication, and may be ‘fueled’ by ineffective communication.”3

Three important sources of conflict have been identified: resources, psychologic needs of individuals or groups, and values. Resource-based conflicts relate to limited resources, common in EM. The premise here resulting in conflict is “I want what you have.” Psychologic needs include power, control, self-esteem, and acceptance. These needs often exist under the conflict’s surface and can be difficult to identify or address. Values (beliefs) are fundamental to conflict. Core values (e.g., religious, ethical, financial) or those involving patient care are difficult to change and therefore generally assume a large role in conflict. Differences in values among people or groups (e.g., health care professionals and physicians with different training) may result in repeated conflicts. The expectations that EPs have of hospital and emergency department (ED) staff regarding work ethic or efficiency, for example, often result in conflict (perceived or real). Under these circumstances, people feel as though their integrity is being questioned, one reason that value-based conflicts are extremely difficult to resolve (Box 1).

Box 1 General Sources of Conflict

Conflict may be broken down into four general types. Intrapersonal conflict occurs when one individual has conflicting values or behavior that causes difficulty for that individual (even though others have similar conflicting values). These are the character traits comprising personality that make conflict more likely. Interpersonal conflicts occur among individuals as a result of differences in opinion or beliefs, communication styles, or goals. These conflicts are the most common in EM and generally occur between EPs and patients, nurses, or consultants. Intragroup and intergroup conflicts occur within or among groups when decision making is necessary (e.g., staff meetings, elections, hiring, scheduling, staffing) (Box 2).

Conflict in medicine is relatively easy to understand if you look at physician attributes, such as a tendency toward perfectionism and delayed social development. Physicians in general do not ask others for help and are encouraged not to by their training. These characteristics are highly adaptive to doctoring, reinforced by training, and rewarded by society. However, these traits may be maladaptive when it comes to communicating and interacting with nonphysicians and can result in conflict and poor conflict management. In fact, physicians tend to avoid unpleasant confrontations because they have not typically developed the skills necessary to address them.4

To assess interpersonal interactions in the health care environment, the responses of nearly 2100 health care providers were reported by the Institute for Safe Medication Practices in a 2003 survey on intimidating behavior. Despite the inherent biases characteristic of survey research, 88% of the respondents had been exposed to intimidating language or behavior. Condescending language, voice intonation, impatience with questions, and reluctance or refusal to answer questions or phone calls occurred far more frequently than the researchers expected. Nearly half of the respondents stated that they had been subjected to strong verbal abuse or threatening body language. Among the conclusions established by the Institute for Safe Medication Practices were that intimidation clearly affects patients’ safety and that gender made little difference.5

However, not all conflict in medicine is the result of intimidation. The ED environment is particularly predisposed to conflict, and conflict occurs for many reasons. Differences in professional opinion and value systems among staff members and patients are only a few of the contributing factors. EPs must interact with individuals from all areas of health care, at all times of the day and night, and during periods of great stress. The result is often tension and conflict. Depending on the size of the hospital or medical staff and the amount of turnover among health care personnel, EPs are not likely to know all the individuals with whom they must interact. This challenges EPs because they are not familiar with each medical staff member’s idiosyncrasies, preferred practice patterns, or communication style. These interactions create even greater difficulties for new EPs lacking a history of a favorable reputation or successful relationship with hospital staff and significantly increase the likelihood of conflict.

Examples of Conflict

Conflict in EM results from a mismatch of expectations between patients, family members, and providers or consultants, as well between nurses, ED staff, and ancillary staff outside the ED. Patients and family members may have unrealistic expectations about their ED experience, not to mention the pain or fear that brought them to the ED. Nurses may have unrealistic expectations of physicians, especially those whom they do not know, and all participants may have widely differing cultural backgrounds. Although gender representation of EPs has become more equal, older EPs tend to be male, whereas nurses are predominantly female. John Grey’s best-selling book Men Are from Mars, Women Are from Venus (HarperCollins, 1992) comments on the frequency of misunderstandings and communication difficulties that exist between genders. Misunderstandings and communication problems exist in the workplace between age groups, known as generational cohorts. Consultants may easily be frustrated with the ED staff, often based on previous unsatisfying experiences. Additionally, each time that consultants are contacted, their practice, social life, or sleep is disrupted. This increase in workload might be enough to ignite conflict.6

Numerous additional factors further explain the high likelihood of conflict in EM. Diversity in training, experience, and perspective often results in differences of opinion between EPs and colleagues from other areas of medicine, including nursing. For example, conflict arises simply from the fact that EPs do not want to send someone home who should not go home, whereas hospital-based physicians or specialists may prefer to not admit patients (or be pressured not to) who do not require admission. These two opposing “forces” create conflict.

The responsibility of patient advocacy assumed by EPs and ED staff often creates conflict because it may not coincide with the interests of the patient or family members. If a patient’s decision-making capacity is impaired or their legal advocate is not present, EPs have the duty to act in the best interest of the patient, state, or society regardless of the patient’s wishes. One common challenge occurs when a patient with a history of substance abuse and chemical dependency demands narcotics for “pain.” An EP’s refusal to prescribe narcotics is certain to create conflict.7 Conflict also occurs when a patient or family member desires admission to the hospital without medical justification or desires consultation with a specialist that is medically unnecessary or inappropriate at that time. Other times an EP may believe that it is in the patient’s best interest to be admitted to an inpatient medical service even if hospitalization may not influence the ultimate outcome, which creates conflict with the admitting service. Conflict may also develop between two services over which service will admit a patient. The EP must mediate this dispute by keeping the patient’s needs and interests at the forefront of the discussion.

Other aspects of EM that predispose to conflict include issues regarding diagnostic testing. Certain tests may have restricted periods of availability. Conflict is inherent when a necessary test available at one period of the day is no longer available despite the full-service expectation of emergency care. Patients (and EPs) are frustrated by this situation and often take out their frustrations on EPs and the ED. Even specialty consultative services are frustrated at these limitations despite their own limited availability for providing patient care. Many tests may not be indicated or may even be harmful to patients. If patients want these tests, conflict is inevitable if the EP serves in the role of patient advocacy while simultaneously serving society’s needs of managing with limited resources.

Perhaps the area most likely to create conflict is ineffective or incomplete communication between two or more parties. Given the cultural and language differences between patients, families, nurses, staff, and consultants, communication challenges prime the ED for conflict. Frustration, unmet expectations, time constraints, and limited staff, equipment, space, and privacy may be overwhelming if communication is suboptimal or barriers to effective communication exist.

Because the specialty of EM is so complex and has tremendous liability associated with its practice environment, many areas of potential conflict have been addressed at the federal, state, and local levels. Common sources of conflict include the patient care responsibilities of on-call consultants, minimum time standards for patients to be admitted and for hospital-based providers to see admitted patients, patient transfers to or from outside hospitals, telephone treatment of private patients who go to the ED, and use of the ED for directly admitting patients or performing various procedures. Hospitals have established guidelines addressing these issues in an attempt to prevent conflict before it occurs. Despite these policies, conflict still occurs. Frequently, these issues result in troublesome outcomes for patients, staff, and hospitals and thereby generate unwanted public attention. EM organizations are addressing these and other areas of potential conflict based on the needs of emergency patients and professionals. As health policy and the specialty of EM evolve, new challenges will be identified with more issues requiring resolution (Box 3).

Box 3 Areas of Conflict Related to Emergency Medicine

Differences in education, background, values, belief systems, and interpersonal styles of communication between emergency physicians (EPs) and others

Commitment to patient satisfaction

Final patient disposition (and who determines this)

Timing of follow-up care and outpatient tests for released patients

Telephone conversations required for patient care issues

Lack of professional respect from primary physicians or consultants

Dual advocacy expected by others for the EP

Teaching hospitals with house staff who may lack communication and conflict resolution skills; have less commitment to the hospital, patients, or emergency department (ED) staff because of temporary scheduling at that hospital or ED; and sense a lack of input, ownership, and control over patients’ (or their own) lives

Patient transfers to or from the ED

Practice variability, including patient handoffs

High patient acuity and volume

Space and patient privacy issues

Federal or hospital reporting mandates

Emergency medicine practice such as caring for multiple patients with limited information, which is associated with great morbidity and mortality

Threat of litigation because of high-stakes clinical challenges and patients’ lack of previous personal relationships with EPs

As the specialty of EM has gained popularity since the 1980s, hospital administrators and medical staff members have increasingly come to recognize the importance of the role of the ED and EPs in delivery of health care. Multiple factors are responsible, such as mandatory exposure to EM in medical school, greater public awareness of our specialty, well-conducted outcomes research regarding EM, and popular television series that represent our specialty in a positive light. Talented medical students from each class are now entering the specialty, and consequently the new generation of primary care physicians and specialty consultants have relationships with members of our profession. Furthermore, many challenging situations that result from the nature of EM practice are less likely to create conflict than in previous decades because hospital administrators seem more willing to collaborate with ED leadership to prevent conflict before it occurs. Many EM leaders are sharpening their administrative skills to allow them greater success when exchanging ideas with hospital leaders. Opportunities for communication, education, and problem solving in areas prone to conflict, especially during “business hours,” is in the best interest of patients and the entire medical staff.

The Importance of Communication

Effective communication is extremely important to the process of conflict resolution. For effective communication to occur, mutual respect and concern must exist between parties, including respect for an individual’s professional and personal choices. Many physicians have difficulty interacting with individuals who do not share similar values, such as work ethic, practice style, or lifestyle. Physicians have often witnessed and learned attitudes, communication patterns, and styles of interaction with staff from mentors, role models, or other authority figures dating back to medical school or training.8

Communication is difficult for various reasons, especially because many physicians are poor listeners. Physicians interrupt patients early and often; these patterns are probably present during communication with colleagues and team members, particularly during stressful situations. In the ED, time constraints make communication challenging, although this style of communication may be necessary in high-acuity situations. Communication is also challenged by the fact that it commonly takes place in a public area. When done by telephone or electronically, visual cues are eliminated, thus making communication even more prone to misunderstanding or conflict. Furthermore, individuals may have unique or different agendas, which makes it even more difficult to communicate efficiently let alone effectively. Past interactions have an impact on future communications—previous negative interactions are far more likely to be remembered than positive ones. The personalities of different specialists often clash, thereby contributing to the likelihood of conflict.

Communication skills of physicians are not always developed with these concepts in mind. The Model of the Clinical Practice of EM, originally published in 2001 and most recently updated in 2009, includes an administrative section on communication and interpersonal issues that lists conflict resolution as one important subheading.9 This model was jointly approved by the American Board of Emergency Medicine, American College of Emergency Physicians, Council of Emergency Medicine Residency Directors, Emergency Medicine Residents Association, Residency Review Committed for Emergency Medicine, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. Another publication by leaders in EM has similarly described the importance of integrating communication and interpersonal skills as defined by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education core competencies to educate EM residents.10 These documents guiding the training of future EPs emphasize the importance of acquiring and mastering these essential skills.

A thorough three-part series of articles that focused on physician-patient communication in EM shared many pearls and problems inherent to our practice.11–13 Other excellent references describe the importance of the physician-patient relationship and EP communication.14,15 The Association of American Medical Colleges, for instance, included communication in medicine as a central aspect of its Medical Schools Outcomes Project, which is intended to guide curricula in all U.S. medical schools. In 2004 the National Board of Medical Examiners began requiring all U.S. medical students to be evaluated in terms of their communication skills, as well as their clinical skills. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education now requires all U.S. residency programs to provide instruction in interpersonal and communication skills.16 Medical licensing bodies have identified the importance of physician communication. As a result, instruction in this area (and that of conflict resolution) is now required in EM training programs.

In clinical practice, physicians characteristically spend much of their time listening and responding to patients’ concerns. Studies have consistently found that clinicians’ interpersonal skills are not always as good as patients or nurses desire. Research has demonstrated that poor communication skills and the lack of team collegiality and trust lead to lower patient satisfaction and worse patient outcomes.17 Interestingly, when physicians and critical care nurses were surveyed to examine such behavior, nearly all physicians did not consider their collaboration or communication with nurses to be problematic, whereas only 33% of nurse respondents rated the quality of this behavior high or very high.18

Interacting with consultants is equally challenging in terms of communication and other areas likely to result in conflict. A multicenter survey from London of 171 newly appointed senior house officers demonstrated the frequency and importance of communication problems, especially with reference to consultations in the ED. These authors concluded that senior house officers serving in EDs could benefit from training in consultation skills in which communication skills are taught.19 It is not clear from this article how much communication training these individuals had before taking on their roles as senior house officers or how much or what type of training they would require. The challenges of interacting with consultants and the difficulty evaluating these interactions are described throughout the EM literature.20,21

A new era of patient care and physician training has developed. These changes are in part a response to the call by several medical organizations for improved training and competence in the communication skills of physicians. The Patient’s Bill of Rights, resident work hour (duty) restrictions, and the Institute of Medicine’s “Report on Medical Error” released in 1999 all raised awareness of the importance of physician communication, interpersonal skills, and effective team functioning to improve patient safety. Though difficult to study, it will be interesting to see whether patient care outcomes and satisfaction within the medical profession improve over time as a result of these changes.

Many issues challenge communication in EM. Time urgency seems to be ubiquitous to all communication in the ED, yet many physicians and health care professionals are unaccustomed to this challenge. Difficulties with challenging patients and the uncertainty of high-risk situations make simple communication in the ED even more difficult. Multiple distractions, frequent interruptions, background noise, concerns about other patients, and frustrations with the ED or the consultation process often result in fractured communication. This situation is likely to create strain in the relationships of colleagues and consultants over time, if not immediately. Therefore, an established communication style and rules (when possible) for unavoidable consultations are integral to smooth operation of the ED.

Rosenzweig defined emergency rapport as a “working alliance between two people,” including recognizing each other’s needs, sharing information, and setting common goals. He went on to write “… rapport implies mutuality, collaboration, and respect, and is built upon a groundwork of words and actions.”14 Although the rapport that Rosenzweig referred to describes physician-patient interactions, it can just as easily (and perhaps more importantly) be used to describe interactions between physician colleagues or health care workers.

Finally, the role that stress has on physician communication must not be overlooked. Besides patient care stressors, it is stressful for EPs to contact physicians about patient care issues, particularly at night.22 It is especially difficult for EPs to contact physicians with hospital leadership roles, with reputations for demeaning behavior, or in senior positions that may affect partnership opportunities or future employment. These situations may directly or indirectly result in less than optimal patient care when an EP’s desire to avoid conflict takes priority. Fortunately, instruction in communication and conflict resolution is required not only in EM training programs and medical schools but also by many other residency programs.

Costs of Conflict

With these issues in mind, what are the costs associated with conflict in EM? Staff morale is likely to be low in EDs with high levels of conflict. Staff turnover and dissatisfaction with the work environment are likely to be high. Management will probably need to address an increasing number of complaints about the ED from it and other areas of the hospital, which takes up valuable administrative time. Conflict interferes with patient satisfaction, throughput, quality of care, and safety. Pride in the ED may decline, thus further reducing morale and creating a potentially debilitating negative spiral.

Research has also shown other costs of conflict. In 1986, Knaus et al. demonstrated that predicted and observed patient death rates appeared to be related to the interaction and communication among physicians and nurses. In this prospective study from intensive care units at 13 tertiary care medical centers, controlled for APACHE II (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II) scores, patient mortality appeared to be related to the degree of intergroup conflict. The authors concluded that the “degree of coordination of intensive care significantly influences its effectiveness.”23 Interpersonal or intergroup conflicts also probably result in decreased patient safety. In the Conflicus study, a survey supported by the European Society of Critical Care Medicine, the authors recorded the prevalence, characteristics, and risk factors for conflict in intensive care units in 24 countries. More than 70% of the respondents perceived conflicts. The most common types of behavior responsible for conflict were personal animosity, mistrust, and communication problems. These conflicts, perceived as severe by more than half, resulted in job strain in those participating in the study.24

The impact that conflict (and poor conflict resolution) has on EPs and ED staff members is significant. In addition to increasing the likelihood that the ED will be an unpleasant place to work, increased stress and decreased job security for the EP and staff are possible. Reduced physician reimbursement with respect to peers may result and cause even greater professional dissatisfaction. These conditions may lead to isolation, withdrawal, or depression. Substance abuse and alcohol or chemical dependency are possible, as are marital strife and family or other personal difficulties in physicians who repeatedly generate conflict with others. Not all stress is perceived or experienced in a similar manner. This is particularly true if staff members are of different gender, culture, training, and generations. Medical errors are likely to occur more frequently, a situation that may compromise patient care and worsen patient care outcomes. Patients are likely to identify conflict among staff members, which may lower patient satisfaction. The emotional and financial costs to patients, staff members (especially nurses), consultants, managers, and administrators are immeasurable if an EP frequently creates conflict and does not possess the skills to identify his or her contribution, minimize it, or resolve it promptly.

Conflict Resolution in Emergency Medicine

If conflict is a disruptive yet inevitable force in EM, conflict resolution and the skills necessary to achieve it are key factors for favorable patient care. Conflict management starts with effective communication between parties. Successful conflict resolution therefore requires parties to demonstrate a willingness to listen fully to the concerns of each other without interrupting or planning a reply. Expressing a willingness to find common ground may help resolve conflict or at least deescalate it. A healthy approach to conflict resolution includes treating the other person with respect, actively listening (e.g., paraphrasing, demonstrating understanding), and clarifying your own needs and perspective.

Conflict resolution has been defined in many ways, but each definition comments on the importance of the present interaction and its impact on subsequent interactions during inevitable future conflict. The 2005 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences was awarded to two researchers of game theory (a branch of applied mathematics) and its role in studying interactions and managing conflict among groups or people. This theory states that the actions of one party in a conflict affect its adversary’s subsequent behavior. John Nash (the subject of A Beautiful Mind) and two other scholars brought public awareness to the concept of game theory when they received the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1994.

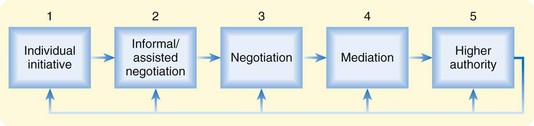

Individuals, groups, and organizations respond to conflict in many ways (Fig. 1). Response styles are generally witnessed (or learned) types of behavior from parents, childhood contacts, mentors, and role models. In other words, an individual’s approach to managing conflict is likely to be adopted as a dominant, often long-term approach that has generally worked for that individual (yet may not work from other people’s perspective). Difficulties in handling conflict may result in unhappiness or lack of success, as well as repeated problematic interactions with staff members and colleagues.

Fig. 1 Preferred pathway of conflict resolution.

(Adapted from Ahuja J, Marshall P. Conflict in the emergency department: retreat in order to advance. Can J Emerg Med 2003;5:429–33.)

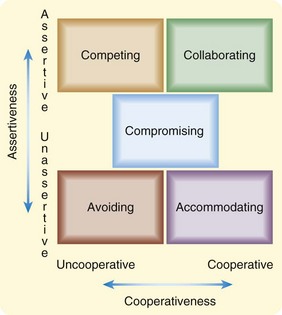

It is relatively easy to recognize that the conflict itself is not necessarily problematic but that the manner in which individuals (or organizations) deal with it may be. Thomas and Kilmann offered a matrix illustrating five distinct responses to conflict that vary along the axes of assertiveness (the extent to which individuals attempt to satisfy their own concerns) and cooperativeness (the extent to which individuals attempt to satisfy other persons’ concerns) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Matrix illustrating five distinct responses to conflict, plotting axes of assertiveness (extent to which an individual attempts to satisfy his or her own concerns) and cooperativeness (extent to which an individual attempts to satisfy the other person’s concerns).

(Adapted from Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument. Available at www.acer.edu.au/publications/acerpress/onlinetesting/documents/TKI.pdf.)

Each of these methods for dealing with conflict has situations that may be effective. The avoiding style uses the premise “I leave and you win” or “I’ll think about it tomorrow.” The goal in this style is to walk away or delay. This style is characterized by low assertiveness and low cooperativeness. Neither party’s concerns are met when this style of conflict resolution is used.

In the accommodating style, one party lets the other win (“It would be my pleasure” is the extreme). This style is characterized by low assertiveness and high cooperativeness and can be either an act of selflessness or one of obeying orders. The goal of this method is to yield or give in, typically by ignoring or neglecting one’s own concerns to accommodate those of the other party. It may be useful for issues of little importance or for creating good will and demonstrating reasonableness. Unfortunately, the accommodator can accumulate ill will if this style becomes dominant and is abused by others. In the extreme, this style may result in poor patient outcomes.

In the compromising style of conflict resolution, both parties “win some and lose some.” Made famous by television personality Monty Hall, “Let’s make a deal” best describes this style. This method has moderate assertiveness and cooperativeness and involves negotiating or splitting any differences of opinion. The goal is to find some middle ground (often expeditiously) and to exchange concessions, unlike the more time-consuming style of collaborating. The compromising method may be helpful in issues of moderate importance, especially when time constraints exist.

In the competing style, a conquest within the contest is the goal of the competitors. This style results in someone winning and someone losing (“My way or the highway”). High assertiveness and little cooperativeness dominate this interaction. This style may have utility when making unpopular decisions, especially for a leader or manager. It tends to create quick results and is often used when bargaining is not an option or the position that one supports is undeniably correct. This style is, however, one-sided and likely to be unpopular with others.

The collaborating style is the most complex style of conflict resolution and yet is the method to adopt whenever possible. Its outcome generally causes both sides to win. Collaboration is one of the main tenets of “win-win” negotiations and involves the philosophy that “two heads are better than one.” Characterized by high assertiveness and high cooperativeness, this style is best used for learning, integrating solutions, and merging perspectives. Digging into the issues, exploring them in depth, and confronting differences are components of this method to manage conflict. This style often results in increased commitment and improved relationships among the involved parties.

The distinct advantages of using the collaborating approach are that relationships are preserved for future interactions and substantive outcomes may be achieved. This approach to dealing with conflict is the most challenging and perhaps takes the longest to negotiate. Consequently, the collaborating approach may be difficult in the time-pressured setting of the ED. However, ideal outcomes can be obtained if the willingness and the resources exist to pursue the collaborative method.

The book Gandhi’s Way: A Handbook of Conflict Resolution examines the principles of moral action and conflict resolution, with the goal of finding satisfying and beneficial resolutions to all involved.25 Gandhi used the term satyagraha, which means “grasping onto principles” or “truth force.” The basic premise of Gandhi’s approach to conflict is to redirect the focus of a fight from persons to principles. He assumed that behind any struggle lies a deeper clash, a confrontation between two views that were each in some measure true. Every fight, according to Gandhi, was on some level a fight between differing “angles of vision” illuminating the same truth.

A contemporary phrase used when dealing with two perspectives is that “the truth lies somewhere in the middle.” Considering this concept, it is relatively easy to see why conflict is so prevalent in society because opposing opinions exist in politics, health care, and interpersonal interactions, to name a few, with little effort being spent on finding the middle ground.

Conflict resolution in EM has a critical role with respect to patient care, as well as positive interpersonal and group relationships. Successful communication is integral to promoting positive interactions among individuals in an effort to prevent (or minimize) conflict before it becomes detrimental. Poor communication between individuals may potentiate persistent conflict and misunderstanding. Building alliances with colleagues may reduce the likelihood and amount of conflict. Team building within the ED and hospital that promotes constructive, creative, and cooperative approaches to conflict management is vital to success.

Challenges to Conflict Resolution

EPs take for granted that difficult interactions occur as part of their daily experience. Some may not find conflict particularly challenging or stressful. Successful EPs must be leaders within the ED despite outside staff not being comfortable with their leadership style. This may be particularly true during stressful situations, a time when EPs gravitate toward the competing style of conflict resolution. Individuals who seldom use the ED (e.g., patients, families, consultants, hospital administrators) may not be comfortable with the environment or its interactions because its structure and culture are “foreign” to them.

Unfortunately, the ED does not always provide the kind of service that health care professionals have come to expect. For example, surgeons in the operating room have instruments handed to them in exactly the way they prefer by designated individuals. This is done in both the patients’ and surgeons’ best interests. In the ED, however, staffing shortages or more pressing cases may result in a consultant being “ignored.” This situation often results in problems for everyone because consultants may take their frustration out on EPs or ED staff. Conflict within the ED is the probable outcome, with the patient and the ED staff suffering. ED staff may feel frustrated that they cannot do better in the eyes of the medical staff, but they are also frustrated by the challenges of staffing, the needs of patients, and the demands of multitasking that prevent them from being more accommodating.

Strategies for Successful Conflict Resolution

With all this conflict occurring in the ED, successful EPs apply strategies to reduce or resolve it in order to preserve the best possible patient and provider satisfaction without compromising patient care. Drs. Marco and Smith describe 10 principles for conflict resolution in EM (Box 4).26 EPs should make it their “standard of care” to refrain from hostile communication and instead persuade others by using intellect and kindness and focusing on patient advocacy and safety.

Box 4

Principles of Conflict Resolution in Emergency Medicine

1. Establish common goals (e.g., to deliver the best or most appropriate patient care possible in a patient-centered fashion).

3. Do not take conflict personally.

4. Avoid accusations and public confrontations.

6. Establish specific commitments and expectations (e.g., Who will see the patient? At what time? Who will assume responsibility for care, including admission or discharge orders and/or instructions?).

7. Accept differences of opinion.

8. ongoing communications (invest in future interactions).

9. Consider the use of a neutral mediator for situations that are not working or become disruptive or emotionally problematic.

Date from Marco CA, Smith CA. Conflict resolution in emergency medicine. Ann Emerg Med 2002;40:347-9.

These principles seem quite reasonable to adopt into practice. On closer inspection, some are similar to the principles described by Robert Fulghum in his popular book (now in its 15th edition) titled All I Really Need to Know I Learned in Kindergarten (Ballantine Books, 2003).

Marco and Smith’s last principle (be pleasant) is good to keep in mind during high-stress situations, when conflict is especially likely to take place. Remember that kindness is contagious. Everyone benefits from a pleasant disposition, regardless of previous negative interactions. Dropping to a lower level of unpleasant or unprofessional interactions during conflict has neither immediate nor long-term benefit and will probably prove detrimental.

O’Mara focused on the interrelationship between communication and conflict resolution. She wrote that “each relationship presents its own potential for ongoing communication dynamics, which may include conflict and misunderstanding,” and added that “appreciating alternative viewpoints and a willingness to adapt are prerequisites for managing interpersonal conflict.”27 Competent EPs are experts at adapting to many situations, with good communication being a fundamental part of their skill set.

Relationships in the Emergency Department

Certain unique aspects of the EP-patient interaction may lead to conflict. First, the nature of this interaction is new, intense, unexpected, brief, and unselected. Neither the patient nor the EP chose the other. Furthermore, the balance of power in any doctor-patient relationship is unequal. Each participant has a different perspective on the nature of the emergency condition. Anxiety, pain, cost of care, lost wages, disability, morbidity, and mortality are of great concern to patients. Furthermore, the timing of care—how long is it appropriate to wait for pain relief, test results, consultants, an admission bed, or discharge instructions—creates conflict (and at times open hostility). In these situations, mismatched expectations and perspectives between a patient and an EP result in conflict that can be intensified by stress, pain, and social, cultural, and language differences.

Perhaps the most intense interactions that EPs have occur with nursing, not only because successful interactions are needed at any given moment but also because these interactions occur frequently. Poor interactions between physicians and nurses are often remembered during subsequent interactions. Nurses are likely to interpret words, communication, and body language in the context of previous interactions that were less than ideal. The doctor-nurse relationship has been examined for years because the ability of these two groups to communicate has an impact on patient care. In groundbreaking research examining these relationships, Stein et al. determined that one of the greatest negative influences on patient outcomes occurs when the nursing profession lacks the opportunity to communicate with physicians.28,29 EDs that encourage authoritarian behavior and attitudes from their EPs are at risk for lower morale among nursing staff. This appears to be true in EDs with training programs because the hierarchic nature of training may extend to communication efforts.27 Enhanced relationship building between nurses and EPs includes improved communication styles and techniques aimed at conflict resolution.

Conflict resolution between EPs and medical staff may be difficult to achieve given the episodic nature of interactions, which often occur at inopportune times for both parties. Although the immediate outcome of the interaction may seem appropriate to the EP (serving as patient advocate), the “scars” from this interaction may be deep. Suboptimal interactions may result in several responses, such as avoiding each other, holding ill feelings toward that individual or department, sharing these feelings with others (“professional slander”), or reporting to administrators of the respective departments. In all cases, the earlier that problem interactions are addressed and the more directly, the better that future outcomes are likely to be. Addressing these difficulties with the goal of conflict resolution is best done in a nonthreatening collegial environment. Taking the “personal” out of the problem is always wise, and seeking assistance from a skilled, unbiased “outsider” is a good idea if these problems are not easily handled. Given physicians’ temperaments and busy schedules, outside resources may be difficult to schedule but may be necessary. Resources include chiefs or chairs of respective divisions or departments, ambassadors or communication experts selected by hospital administrators who specialize in interpersonal relationships, ombudspersons, mediators, human resource managers, social workers, licensed therapists, psychologists, and other mental health professionals. These resources may be especially necessary if differences in age, gender, culture, ethnicity, rank, or position exist or if these problems are particularly difficult or have been continuing for some time.30

An additional strategy to foster successful conflict resolution includes engaging with colleagues and staff outside the ED. EPs who participate in medical staff affairs or serve on hospital committees share time with colleagues when stress is not maximal. Positive interactions and sharing common interests during these activities are likely to build alliances, which may reduce the amount and intensity of conflict. Participating in or organizing shared educational activities with colleagues (e.g., journal review, didactic sessions, question-and-answer opportunities) is also important, as long as the goal is education and not criticism. These opportunities allow colleagues with different training to communicate patient care principles, to discuss areas of changing or uncertain practice, and to resolve potential conflict before it occurs. These exchanges allow consultants the opportunity to recognize our knowledge and to see that EPs are interested in gaining skills to provide better patient care and to better accommodate specialty consultants. Furthermore, it is important for EPs to attend social activities within or outside the hospital, where they can get to know medical staff members. Time with non-EM colleagues away from the stressful environment of the ED is a wonderful opportunity for building relationships. This may allow more successful or even faster conflict management in the future.

Much of the best writing on conflict resolution comes from the business literature. The Harvard Negotiation Project found that a working relationship depends on the ability to balance reason and emotion and to understand each other’s interests or position. In the seminal works Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In and Getting Past No: Negotiating Your Way from Confrontation to Cooperation, the authors discuss negotiation in terms of it being an everyday experience or a fact of life. These resources describe the method of principled negotiation, which decides issues on their merit rather than through a haggling process focused on what each side says it will and will not do. This method suggests looking for mutual gains whenever possible. When interests conflict, individuals should insist that the result of negotiation be based on some fair standards independent of the will of the other side. This method of principled negotiation is therefore “hard on the merits, soft on the people”31,32 (Box 5).

Box 5 Strategies for Conflict Resolution from the Business World

Separate the people from the problem.

Move from positions to interests.

Avoid rushing to premature solutions.

Invent options for mutual gain.

Select and use objective criteria by which to evaluate the fairness of the options generated.

Use negotiation “jujitsu,” wherein one negotiator embraces the other’s positions rather than resisting them.

Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In recommends that negotiators develop their best alternative to a negotiated agreement, which serves as the basis for exploring and evaluating options.31 This approach involves thinking carefully about what will happen if a negotiated agreement cannot be reached while simultaneously serving as an impetus to engage in a process with agreement as the outcome.

In his book You Can Negotiate Anything, Cohen offers three crucial variables in negotiations: power, time, and information.33 Power is in the hands of the EP in the sense that he or she may use the phrase “I am not comfortable with that (advice),” or “I would like you to come in and see the patient now (let’s discuss this at the bedside).” Power may, however, undermine negotiation and conflict resolution. Those with power have less to gain from negotiation and often walk away from the process (avoidance style of conflict resolution) because withholding participation may maximize their power (or at least not result in its loss). Many authors believe that a collaborative approach to conflict resolution minimizes the role of power in negotiations.

Time is not always on the side of the EP, and it may shift the balance of power to the consultant. Again, the EP must serve in the role of single advocacy for the patient; dual advocacy for both the patient and the consultant may result in a conflict of interest and thus jeopardize patient care.

Information may be shared among parties. The EP has information about the patient’s condition at the bedside in real time, and the consultant often has a special knowledge base or skill set to offer the patient or the EP. Parties may exchange information that benefits themselves, patients, or both, which must be considered in the conflict resolution “equation.”

Cohen’s mantra for successful bargaining is to “be patient, be personal, [and] be informed.”33 Preparation is important before negotiations begin, although this is sometimes difficult in EM. Several opportunities exist to increase preparation before consultation (which is a negotiation). Efforts to have the patient’s identifying information available at the start of the conversation, reviewing the laboratory and radiology results before the call if possible, and clearly stating specific goals of the contact (“I need you to come in and evaluate this patient,” or “I need your input on testing, treatment, or follow-up care strategies for this patient”) help reduce conflict before it occurs. Communicating in the consultant’s language and refraining from making suggestions (even obvious ones) unless asked are excellent strategies.

Additional opportunities to achieve conflict resolution include communication that begins with careful, empathetic listening because this allows the other party to feel heard.34 Avoiding negative comments or ridicule (especially public) and depersonalizing the conflict are healthy approaches to its management. This allows the other party to maintain self-esteem and self-respect. It is important to remain objective and maintain composure while focusing on the issues. Be careful when responding to emotions because it may result in unintended statements with consequences. Silence and time (to compose oneself or gather thoughts) are powerful tools that may deescalate conflict35 (Box 6).

Box 6

General Principles of Conflict Management

Create trust: Occurs by understanding and being perceived as understanding the other party’s issues.

Effective listening: The first step toward understanding the problem. Be careful to not project your understanding of the situation based on your experiences; the present situation and experiences are those of the individual. Appropriate responses following careful listening are neutral and without criticism. They allow concerns to be expressed, accepted, clarified, and perhaps validated. Empathy is a wonderful response to integrate at this stage of effective listening.

Eye communication: Allows the speaker to feel heard and to feel that what he or she is saying matters.

Focus on the issue, not on the position: Bring the discussion or negotiation back to a level playing field by concentrating on the issue.

Separate the individual or group of individuals from the problem: Effectiveness in dealing with conflict in part depends on this ability. Success requires the recognition that most people are not trying to create problems but in fact are trying to meet their own needs. The key is to remember that others have different, yet equally valid perceptions of reality from ours. Therefore, understanding their underlying or preexisting perceptions is important for resolving conflict.

Use caution when responding to emotion: Responding emotionally to an emotional situation reflects loss of control. Maintaining composure and continuing to focus on the issue enhance the resolution process. Silence is an effective alternative response to an emotional interpersonal conflict. The power of silence is profound, and it often deescalates heated situations.

Adapted from Strauss RW, Strauss SF. Conflict management. In: Salluzzo RF, Mayer TA, Strauss RW, et al, editors. Emergency department management: principles and applications. St. Louis: Mosby; 1997.

Benefits of Conflict Resolution

Dr. Andrew recommended “paraphrasing the communication back to the complainer” and “expressing a willingness to find a common ground.”3 These recommendations are critical because conflict is often generated (and many times escalated) from fear that a concern was not heard or validated. She described four A’s that assist in conflict resolution to support these ideas:

1. Acknowledge the conflict (“I understand your concern. I can tell you are not pleased with what has taken place.”)

2. Apologize (blamelessly) for the situation (“I’m sorry this situation occurred.”)

3. Actively listen to the concern (“Please go on. I want to hear more about this.”)

4. Act to amend (“I promise I will act to fix this situation and [try to] make certain it doesn’t happen again to someone else.”)3

Working together with others can create community, which affords the opportunity to develop creative solutions to resolve conflict. In this manner, conflict can be productive rather than destructive. When possible, an attempt at arriving at solutions acceptable to all involved parties should be made. Addressing differences in values resulting in the conflict (or making resolution difficult), establishing effective styles of communication (including active listening without interruption), and having all parties commit to the mutually satisfying resolution of these concerns are essential factors to success. Given the challenging dynamics of EDs and the instability of groups, prompt conflict resolution is vital to the health of the system. It is especially important to acknowledge shared responsibilities for problems (and solutions) within the ED environment. In this manner, stakeholders have ownership, pride, and incentive to correct the situation. Prevention of potential conflict remains the superior approach to conflict resolution. When this is not possible, early intervention by trained and respected individuals in a safe haven for discussion should be considered.

Skillful negotiating techniques embody an empowering, active, constructive, and positive approach to resolving difficulties and often yield successful outcomes or incremental change over time. Numerous short- and long-term benefits result from successful conflict resolution (Box 7).

Box 7 Positive Outcomes of Conflict Resolution

Improved communication with patients and colleagues

Reduced stress levels and improved staff morale

Increased workplace productivity (and possibly reimbursement) and reduced expenditures related to conflict

Promotion of healthy relationships with colleagues and staff

Improved patient, staff, and physician satisfaction

Decreased staff turnover (increased staff retention)

Prevention of future conflict or at least resolution of future conflict more effectively and expeditiously

Failure of Conflict Resolution

When it is not possible to resolve conflict in real time, it may be necessary to have an outside mediator work with the parties. Authors on this topic reported in the Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine that “while early intervention through negotiation between conflicted parties is often the most desirable option, there may be situations where a dispute involves power imbalances, in which case resolution may be more achievable using the neutral facilitative approach provided by a third party mediator or arbitrator.”1 Dr. Andrew defined mediation as a “process that takes negotiation to its highest level, employing a neutral party to help hurt and angry people communicate effectively and draft collectively a solution that is greater than the sum of the problems.”4 Mediation should be nonadversarial. It should be scheduled at an unbiased location, away from the ED, at a time convenient for all parties. Scheduling the session takes time, and a good mediator meets with both parties privately before arranging a joint meeting. It is important that rules be established and agreed on before the meeting. Such rules may include treatment of the other party with respect, an agreement to not interrupt or use negative nonverbal communication, confidentiality, and allowance of time for each party to process ideas and information. This is important because the conflict and the meeting are likely to create emotional intensity that can interfere with the ability to process information. Even if the parties do not like or respect each other, they should at least accept that they have different value systems. This seemingly small concession has a tremendous impact on resolving conflict. Finally, agreeing ahead of time to consider all ideas as valid, even if these ideas are not implemented, offers both parties more confidence that their ideas will be heard.

Red Flags Associated with Conflict and Inadequate Conflict Management

Because conflict is likely to result in many problems for patients and staff, there are “red flag” areas of conflict and poor conflict management to recognize. In addition to the costs of conflict described earlier, fear of approaching or interacting with EPs or staff members to avoid conflict places patients at risk. For example, an EP may not consult a specialist because of some unresolved conflict in an area outside his or her expertise. Clearly, this behavior jeopardizes patient care and does nothing to improve subsequent interactions.

![]() Red Flags

Red Flags

Not being aware of personal feelings about conflict. This includes ignoring your “triggers” (words or actions that immediately provoke an emotional response, such as anger or fear). These triggers could be a facial expression, a tone of voice, finger pointing, or a certain phrase. Once you are aware of your triggers, you are more likely to be able to control your emotions and responses.

Not listening to what the other party is saying, including what is not being said. Active listening goes beyond hearing words; it requires concentration and body language that says you are paying attention to the other party. Careful listening means avoiding thinking about what you are going to say next in response to what is being said.

Not acknowledging or understanding differing perspectives, backgrounds, agendas, or goals. This requires being flexible and open-minded.

Not differentiating among positions, their meanings, needs, and facts. It is important to have accurate facts.

Not offering the other party room to admit to errors in judgment. This includes admitting your own errors.

Not recognizing the importance for both sides to feel as though they “won” something (“win-win” collaboration)—in other words, not allowing the other party to experience a winning feeling. Winning at another person’s expense is not winning at all and has no role in conflict resolution. Thus, it is important to include more than one solution to a conflict.

Failing to learn from previous mistakes in conflict resolution. This process is difficult and takes practice.

Not having a plan to follow up and monitor the agreed-on practices. It is important to decide who will be responsible for the specific actions of the plan and how these actions will be monitored (and enforced if necessary).

Summary

Conflict has been described as a natural consequence of incompatible behavior and unmet expectations.35 The preferred strategy for managing conflict is to prevent its occurrence, not easy to do in EM. Effective communication between individuals and within groups in which parties are respected and heard produces an environment of trust. This results in the likelihood that conflict will be resolved more effectively, which benefits everyone. EPs should be aware of their types of behavior and styles of interaction that increase conflict in an environment predisposed to conflict. Furthermore, EPs must strive to understand the principles of conflict and conflict resolution, including effective communication and strong interpersonal and listening skills. Articles discussing professionalism in EM describe the commitment that EPs must make to our profession: suspension of self-interest, honesty, authority, and accountability.36 These elements are also essential for successful conflict resolution. One article concluded that “Medicine can never succeed as a transaction; it can only succeed as a partnership, a trusting exchange with patients, which is the hallmark of professionalism.”36 The attitudes of and types of behavior by EPs that enhance trust through placing the patient’s needs above other interests serve as the operative definition of professionalism.37 This philosophy, extended beyond patients to hospital staff members and consultants, suggests the approach that physicians should take to resolve conflicts in EM. Effective communication and interpersonal skills promote a culture of teamwork, which along with professionalism and conflict management techniques, are essential components of successful EM practice (Box 8).

Box 8 Comprehensive Approach to Successful Conflict Resolution

Accept the existence of the conflict.

Separate the person from the problem.

Clarify and identify the nature of the problem creating conflict.

Deal with one problem at a time, beginning with the easiest.

Engage the respective parties in an environment of impartiality.

Listen with understanding and interest rather than evaluation.

Identify areas of agreement; focus on common interests, not on positions.

Attack data, facts, assumptions, and conclusions, but not individuals.

Brainstorm realistic solutions in which both parties benefit.

Use and establish objective criteria when possible.

Do not prolong or delay the process.

Evaluate and assess the problem-solving process after implementing the plan (follow up periodically).

Taoism has as its quintessential ideas guidelines for conflict resolution, which it describes as realizing harmony with one another and achieving consonance with nature. The Art of War, written 2400 years ago by the Chinese military philosopher Sun Tzu, remains one of the most highly influential texts today. Many translations of this work share important philosophic points, such as “winning without fighting” (no conflict) and “knowing your enemies and yourself” (to prevent conflict or, if inevitable, to be more successful in its resolution). In conflict, one must consider the other party an equal, with real issues and needs, and not an adversary to be overcome. Winning at another’s expense does not work if future collaboration is necessary, as is generally the case in EM practice. Successful conflict resolution requires collaboration in which both sides have at least some of their needs met, even if to varying degrees. If one side does not respect the other or if judgment is passed, confrontation will continue and conflict is not likely to be resolved. Truly collaborative solutions, such as those in which both parties feel supported, respected, and satisfied that their needs were met, should be the focus behind the resolution of any conflict.

Acknowledgment

Dr. Garmel lectures on the topic of conflict resolution in emergency medicine as part of the National Residency Leadership Curriculum for emergency medicine residents. This curriculum is supported by the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP), Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, Council of Emergency Medicine Residency Directors, and Emergency Medicine Residents Association. The Colorado ACEP chapter received a grant that provided funding for the Core Leadership Attribute Seminar Series.

1 Ahuja J, Marshall P. Conflict in the emergency department: retreat in order to advance. Can J Emerg Med. 2003;5:429–433.

2 Garmel GM. Conflict resolution in emergency medicine. In: Adams JG, Barton ED, Collings J, et al. Adams emergency medicine. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2008.

3 Andrew LB. Communication, conflict resolution, and negotiation. In: Bintliff SS, Kaplan JA, Meredith JM. Wellness book for emergency physicians. Dallas: American College of Emergency Physicians; 2004:48–50. Available at http://www.acep.org/Content.aspx?id=32184&terms=Wellness Accessed 12/11/10

4 Andrew LB. Conflict management, prevention, and resolution in medical settings. Phys Exec. 1999;25:38–42.

5 Institute for Safe Medication Practices. Practitioners speak up about this unresolved problem. Part 1. Institute for Safe Medication Practices Newsletter. March 11, 2004. Available at http://www.ismp.org/MSAarticles/Intimidation.htm Accessed 12/11/10

6 Rogers DA, Lingard L. Surgeons managing conflict: a framework for understanding the challenge. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203:568–574.

7 Paterniti DA, Fancher TL, Cipri CS, et al. Getting to “no”: strategies primary care physicians use to deny patient requests. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:381–388.

8 Garmel GM. Mentoring medical students in academic emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:1351–1357.

9 Perina DG, et al. 2009 Model of the clinical practice of emergency medicine. Available at (Chair) http://www.acep.org/content.aspx?id=29580 Accessed 4/6/12

10 Chapman DM, Hayden S, Sanders AB, et al. Integrating the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education core competencies into the model of the clinical practice of emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:674–685.

11 Knopp R, Rosenzweig S, Bernstein E, et al. Physician-patient communication in the emergency department. Part 1. Acad Emerg Med. 1996;3:1065–1069.

12 Totten V, Knopp R, Rosenzweig S, et al. Physician-patient communication in the emergency department. Part 2: communication strategies for specific situations. Acad Emerg Med. 1996;3:1146–1153.

13 Rosenzweig S, Knopp R, Freas G, et al. Physician-patient communication in the emergency department. Part 3: clinical and educational issues. Acad Emerg Med. 1997;4:72–77.

14 Rosenzweig S. Emergency rapport. J Emerg Med. 1993;11:775–778.

15 Mahadevan SV, Garmel GM. The outstanding medical student in emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8:402–403.

16 Lurie SJ. Raising the passing grade for studies of medical education. JAMA. 2003;290:1210–1212.

17 Feiger SM, Schmitt MH. Collegiality in interdisciplinary health teams: its measurement and its effects. Soc Sci Med. 1979;13A:217–229.

18 Thomas EJ, Sexton JB, Helmreich RL. Discrepant attitudes about teamwork among critical care nurses and physicians. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:956–959.

19 Williams S, Dale J, Glucksman E. Emergency department senior house officers’ consultation difficulties: implications for training. Ann Emerg Med. 1998;31:358–363.

20 Holliman CJ. The art of dealing with consultants. J Emerg Med. 1993;11:633–640.

21 Rosenzweig S, Brigham TP, Snyder RD, et al. Assessing emergency medicine resident communication skills using videotaped patient encounters: gaps in inter-rater reliability. J Emerg Med. 1999;17:355–361.

22 Baerlocher MO. The overnight smackdown: avoiding on-call arguments. CMAJ. 2009;180:252.

23 Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, et al. An evaluation of outcome from intensive care in major medical centers. Ann Intern Med. 1986;104:410–418.

24 Azoulay E, Timsit J-F, Sprung CL, et al. Prevalence and factors of intensive care unit conflicts: the Conflicus study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:853–860.

25 Juergensmeyer M. Gandhi’s way: a handbook of conflict resolution. Berkeley, Calif: University of California Press; 2002.

26 Marco CA, Smith CA. Conflict resolution in emergency medicine. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;40:347–349.

27 O’Mara K. Communication and conflict resolution. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1999;17:451–459.

28 Stein LI. The doctor-nurse game. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1967;16:699–703.

29 Stein LI, Watts DT, Howell T. The doctor-nurse game revisited. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:201–203.

30 Chervenak FA, McCullough LB. The identification, management, and prevention of conflict with faculty and fellows: a practical ethical guide for department chairs and division chiefs. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:572.e1–572.e5.

31 Fisher R, Ury W, Patton B. Getting to yes: negotiating agreement without giving in, 2nd ed. New York: Penguin Books; 1991.

32 Ury W. Getting past no: negotiating your way from confrontation to cooperation. New York: Bantam Books; 1993.

33 Cohen H. You can negotiate anything. New York: Bantam Books; 1980.

34 Anderson EW. ABC of conflict and disaster: approaches to conflict resolution. BMJ. 2005;331:344–346.

35 Strauss RW, Halterman MK, Garmel GM. Conflict management. In: Strauss and Mayer’s emergency department management. McGraw-Hill; 2012. in press

36 Finkel MA, Adams JG. Professionalism in emergency medicine. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1999;17:443–450.

37 Adams JG, Schmidt T, Sanders A, et al. Professionalism in emergency medicine: SAEM Ethics Committee. Acad Emerg Med. 1998;5:1193–1199.

38 Tohki R, Garmel GM. Resident professionalism in emergency medicine. Ca J Emerg Med. 2006;VII(3):55–58.