CHAPTER 3 Research Foundations, Methods, and Issues in Developmental-Behavioral Pediatrics

THE UNIQUE NATURE OF DEVELOPMENTAL-BEHAVIORAL PEDIATRIC RESEARCH

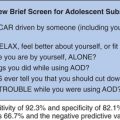

DBP research often aims to study the full spectrum of child development and behavior: from normal variations to concerns or problems to clinical disorders. One of the driving forces for establishing the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders was to standardize the diagnostic criteria for disorders to foster consistency in research in mental illness.1 Research that incorporates the continuum of developmental and behavioral difficulties must establish reliable and valid outcome measures for subthreshold or problem conditions or criteria for identifying where on the bell-shape curve of behavior or development is the appropriate cutoff for defining a concern or a problem. Although achieving reliability in delineating the diagnostic criteria for a mental illness may be challenging, it is often even more elusive for a behavioral problem or personality trait. One common approach is to inquire whether the characteristic of interest (e.g., attention) is believed to occur significantly more often in one person than in typical peers of the same age or developmental level and to require an association with some perceived impairment (e.g., attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder [ADHD]). This approach often introduces a reliance on subjective, self-reported measures of perceived impairment or relative deviation from perceived norms that can compromise validity and produce a reporting bias.

Because DBP often assumes an ecological perspective, researchers are more apt to look critically at sociocultural influences on child development and behavior. Such factors are difficult to measure, even harder to report accurately, and far more difficult to interpret or explain. The use of race and ethnicity as explanatory variables illustrate the complexity of this issue.2 Researchers who understand the complexity of social and cultural influences appreciate the futility of controlling for all relevant influences within an ecological model.

Despite these challenges, the complexity of research design issues in DBP fosters its richness. The multiple perspectives and theories and the diversity of available methodological approaches enable the construction of rich, multidimensional theoretical models. Researchers must necessarily explore not only outcome measures but also mediators and moderators (see Chapter 2). The complexity is increased by the factor of time and the challenges inherent in measuring one construct in the context of a child’s developmental trajectory. For example, in studies of the influences of early childhood experiences on later language outcomes, investigators need to consider not only the multiple environmental, familial, cultural, and community factors that may influence language development but also the reality that developmental processes are not static in the individual child. Parsing out how much of change in language development is attributable to the normative process of child development ot to inherent deficits in the child, social, environmental, family or community factors, or the unanticipated effect of uncontrolled historical events (such as changes in preschool policy or educational interventions) can be daunting.

CROSS-CUTTING METHODOLOGICAL AND THEORETICAL ISSUES

Incorporating Child Development within Child Development Research

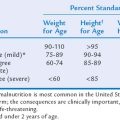

Central to any research in the area of child development is an appreciation that children’s capabilities and behavior change over time as a result of developmental processes, independent of other factors or interventions. Measures of skills or capabilities therefore need to be adjusted and compared with norms for different ages/stages, introducing analytical concerns for cross-sectional studies involving children of different ages or developmental stages. Measurements of the effect of interventions provided over time may also be compromised by analytical concerns inherent in measuring the same domain at different developmental stages, which may necessitate the use of different age/stage-appropriate instruments or, at the very least, correction for age/stage. In addition, measurement of children’s abilities may be confounded by the child’s developmental capacity to understand instructions and communicate comprehension. For example, young children have been described as having difficulty appreciating the perspective of someone else. It is possible that such difficulty may result, at least in part, from limitations in their ability to comprehend the task requested, their language ability to communicate their understanding, or the researcher’s ability to communicate the task required. Research on young children’s understanding of the concepts of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) initially suggested that young children’s understanding of core concepts of illness was significantly limited developmentally, which seriously constrained their capacity to benefit from educational interventions; however, subsequent research demonstrated that a developmentally based educational intervention could result in dramatic gains in young children’s conceptual understanding in this area.3 In other words, what appeared at first to be a limitation in children’s ability to learn was subsequently found to represent limitations in adults’ understanding of how to teach effectively and/or in researchers’ ability to measure validly children’s underlying comprehension.

The Biopsychosocial Model

The biopsychosocial model emphasizes the complementary influences of genetic predisposition, environmental factors, and experience on development and behavior. DBP research encompasses basic science and social science research methods, allowing the demonstration of causal mechanisms by which environmental and experiential factors alter basic biological processes. For example, to study the influence of early stressful experience on later hyperactivity of neurons that release corticotropin-releasing factor as a cause of adult anxiety or depressive disorders, both stressful experiences and neuronal function must be measured, and the potential confounders of both must be understood.

Qualitative Methods

Qualitative research methods are most appropriate in situations in which little is known about a phenomenon or when attempts are being made to generate new theories or revise preexisting theories. Qualitative research is inductive rather than deductive and is used to describe phenomena in detail, without answering questions of causality or demonstrating clear relationships among variables. Researchers in DBP should be familiar with common ethnographic methods, such as participant observation (useful for studying interactions and behavior), ethnographic interviewing (useful for studying personal experiences and perspectives), and focus groups (involving moderated discussion to glean information about a specific area of interest relatively rapidly). In comparison with quantitative research, qualitative methods entail different sampling procedures (e.g., purposive rather than random or consecutive sampling; “snow-balling,” which involves identifying cases with connections to other cases), different sample size requirements (e.g., the researcher may sample and analyze in an iterative manner until data saturation occurs, so that no new themes or hypotheses are generated on subsequent analysis), different data management and analytic techniques (e.g., reduction of data to key themes and ideas, which are then coded and organized into domains that yield tentative impressions and hypotheses, which serve as the basis of the next set of data collection, continuing until data saturation occurs and final concepts are generated), and different conventions for writing up and presenting data and analyses. The strength of the findings is maximized through triangulation of data, investigator (e.g., use of researchers from different disciplines and perspectives or several researchers to independently code the same data), theory (i.e., use of multiple perspectives), or method (e.g., use of focus groups and individual interviews to obtain complementary data).

Placebo Effects

The use of a placebo in psychosocial interventions is less clear than in medication trials. Some studies utilize alternative interventions (e.g., the control group for a study of hypnosis to decrease pain in children with a chronic condition might receive education about an unrelated component of their condition). The limited empirical evidence on how “counseling” or “therapy” works contributes to difficulties in controlling for all components that may be involved in a therapeutic or placebo effect. Furthermore, if individuals report less pain or subjective discomfort after the use of an interpersonal placebo intervention, such as the psychoeducational component of the example just described, should the placebo then be considered as a possibly effective, alternative form of treatment (e.g., perhaps informal group support occurred as a result of the psychoeducational sessions that decreased parental anxiety, that in turn decreased the child’s anxiety and perceptions of discomfort or pain)?

ETHICAL ISSUES

The Ability to Provide Consent and Assent

Research in DBP often involves participation of research subjects who have cognitive/developmental limitations that affect their ability to provide consent or assent. Studies may also involve the collection of data from individuals who report on characteristics of the family, community, or other groups. In such situations, ethical concerns may be raised about the ability of the individual (especially when that individual is a minor) to provide potentially sensitive information about others.4

IMPLICATIONS FOR RESEARCH TRAINING IN DEVELOPMENTAL-BEHAVIORAL PEDIATRICS

Training in Quasi-experimental and Observational (Epidemiological) Research Designs

The majority of research in DBP does not involve double-blind, randomized, controlled trials (RCTs). Double-blind RCTs are conducted in studies of psychopharmacological therapy for such conditions as ADHD and autistic spectrum disorders, and single-blind RCTs are conducted for behavioral and educational interventions for the treatment or the prevention of developmental and behavioral disorders. Examples of the latter include the High/Scope Perry preschool study5 and the Hawaii home visiting study.6 However, many important nonpharmacological interventions in DBP are difficult to randomize. New educational interventions in the school setting, for example, are likely to be offered to whole classes or schools rather than to randomly selected students, with other classes in the same school or other schools in the same district acting as controls after being matched on a variety of characteristics. These “quasi-experimental” designs play an important role in DBP research.

Research training should, therefore, include education in quasi-experimental designs. A quasi-experimental design is similar to an experimental design except that it lacks the important step of randomization.7 The most common type of quasi-experimental design involves the use of nonequivalent matching groups. One cohort of children receives an intervention, whereas another matched cohort acts as a control or receives an alternative intervention. Quasi-experimental designs such as this, although frequently the only possible design for some nonpharmacological interventions, suffer from the threat to their validity of selection bias. Education concerning the identification of selection bias and methods to reduce its effect (such as matching, sample stratification, and adjusting for potential confounders) is important for the developmental-behavioral researcher.8

Furthermore, researchers in DBP frequently seek to study the effects of harmful and protective factors on childhood outcomes in normative or at-risk populations or to elucidate underlying constructs associated with or causing various outcomes. The study of naturally occurring constructs or of potentially harmful factors leads to choosing observational designs rather than experimental designs.8

Training in Qualitative Methods

Qualitative research designs play an important role in developmental-behavioral research. For example, in one study, investigators sought to understand Latina mothers’ cognition and attitudes concerning stimulant medication for ADHD and how these factors might determine adherence to medication regimens and resistance to starting drug therapy.9 Qualitative methods are the best approach to this type of research question, with which investigators seek to understand the perspectives of persons or groups and to develop and revise research hypotheses. Therefore, a strong foundation in qualitative methods is important for DBP researchers. Training should include providing an understanding of the types of research questions that qualitative methods are best suited to answer, skills in the use of common ethnographic methods, facility with methods used for data coding and data reduction, and familiarity with methods used to ensure trustworthiness of qualitative research results.10–13

Training in the Development and Validation of Testing Instruments and Scales

Many of the outcomes and constructs of DBP lack well-standardized or validated measures. Furthermore, even well-validated and reliable measures developed for a general population may not be appropriate for use in a special population. Therefore, the development and validation of such measures are frequent subjects of a research study or are common components of a larger research project. For example, in one study, investigators sought to measure self-efficacy and expectations for self-management among adolescents with chronic disease (diabetes) and to determine the effects of these factors on disease management outcomes.14 However, there existed no scale for measuring self-efficacy or measuring expectations for self-management of diabetes. Therefore, the researchers had to develop their own scales and test the reliability and validity of those scales before answering the underlying research question. In another study, researchers wanted to determine whether the Pediatric Symptom Checklist,15 a commonly used screen for behavior problems in a general population, was valid for use in a chronically ill population.16 In this case, the researchers sought to test the construct validity of a well-validated scale on a new population.

Therefore, research training should include skills in test development, including testing for reliability (with measures such as test-retest reliability and interrater reliability), internal consistency, and validity. The researcher should be familiar with the different types of validity, including content and sampling validity, construct validity, and criterion-related validity, and be able to use methods that assess them.17

Training in the Use of Large Secondary Datasets

Research publications increasingly reflect the efforts of researchers to mine large secondary datasets, including federally funded national databases, administrative databases, and electronic medical records, for information related to delivery of care and outcomes in DBP. This type of research has been especially fruitful in the study of ADHD. In one published study, the researchers used the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey and the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey to study regional and ethnic differences in the diagnosis of ADHD and receipt of psychotropic medications for that diagnosis.18 In another, investigators used health maintenance organization (HMO) data to compare total health care costs for children with and without ADHD.19 Researchers at the Mayo Clinic have used their computerized medical records database, which has information on 95% of the population in Olmstead County, Minnesota, from 1977 to the present. They have studied ADHD, autism, psychostimulant treatment, and learning disabilities, among other topics.20–22 Finally, Rappley and colleagues used Medicaid database information to sound an alarm about apparent excessive prescription of psychotropic medication for preschool children.23

Training in Multivariate Statistical Analyses

As a consequence of the frequent use of quasi-experimental and observational study designs in DBP research, training in statistical methods that adjust for confounding factors and that determine unique and independent contributions of hypothesized factors to patient outcomes is essential. Research training should focus on such commonly used statistical techniques as multiple linear regression,24 analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), and logistic regression.25 Although training goals may vary in the level of expertise from “educated consumer” of statistical services to independent producer of statistical analyses, the DBP researcher should be skilled in the interpretation of the results of these analyses, knowledgeable about the different types of statistical models, and able to recognize the pitfalls and limitations of these techniques.

Measurement of psychological or behavioral characteristics with scales frequently necessitates an analysis of data for the underlying factors or constructs embodied by the measured variables. Factor analysis is employed to reduce measured variables to a smaller number of underlying “latent” variables. Factor analysis is frequently used to explore and confirm the construct validity of a new scale or a previously validated scale for use in a new population. In addition, factor scores may be used to substitute for variables in other statistical analyses. Because research in DBP often involves the development of new measures for abstract outcomes, factor analysis is a useful statistical method for DBP researchers. For example, factor analysis was used to develop new scales in the previously noted study14 in which investigators sought to compare self-efficacy and expectations for diabetic management to diabetes self-management outcomes. They then used the scores on these scales, including a separate score for each of two identified factors, in multiple regression analyses of the relationships between these constructs. In another previously cited study,16 researchers used factor analysis to compare items on the Pediatric Symptom Checklist15 in a chronically ill population with those in a general population.

Therefore, an understanding of the role of factor analysis in the development and validation of testing instruments and scales is important for the DBP researcher. Familiarity with methods of extraction of factors from the collected data, procedures for keeping and discarding factors, and other aspects of factor analysis are an important part of research training.26–28

Training in Neurobiological and Genetic Science

A growing body of research has focused on the use of neuroimaging techniques to elucidate brain function and anatomical location of activation during behavioral and psychological tasks. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has become an important tool in developmental-behavioral research. Unlike positron emission tomography (PET) and single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), fMRI does not include the injection of radioactive materials. Therefore, children can undergo imaging repeatedly, which allows for study during different disease states or throughout developmental changes. It also allows the researcher to study healthy children at low risk for the disorder under investigation. For example, using fMRI, researchers have sought to localize the areas of brain activation with attention or reading tasks in children with ADHD or dyslexia and compare those activation patterns with patterns in normal children.29,30 Other researchers have used brain proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy to identify children with brain creatine deficiency who have global developmental delay.31 It is likely that functional neuroimaging techniques will play an important role in the future study of the neurobiological basis of developmental and behavioral problems or conditions. Future researchers should receive training in the science of these techniques to enable them to collaborate with neuroradiologists in answering questions that span the spectrum of the biopsychosocial model.

Similarly, training in the genetics of developmental and behavioral disorders is important for researchers. Understanding the role of genetics will empower the researcher to incorporate genetics into research hypotheses and methods. One area that should be considered for inclusion in research training is quantitative behavioral genetics.32 In this field, investigators seek to determine the proportion of variance in behaviors resulting from heritability, shared environment (family, neighborhood, home environment), and unshared environment (e.g., peers, teachers, differential parental treatment, illnesses). For example, one article focused on the quantitative behavioral genetics of child temperament.33

Another important area for research is the association of behavioral phenotypes with molecular genetic findings and variations. Behavioral and psychoeducational profiles have been elucidated through research for velocardiofacial, Williams, Down, Prader-Willi, fragile X, and Turner syndromes, among others.34 Studies have shown associations of these behavioral and psychological characteristics with specific molecular genetic patterns. The availability of molecular genetic techniques has also allowed scientists to study behavioral phenotypes of subjects with “milder” genetic deficits. For example, in one study, researchers found an association of fragile X premutation (carriers) with autistic spectrum diagnosis through the use of molecular genetic studies.35 Other researchers have been studying polymorphisms in specific genes, such as the dopamine D4 receptor gene (D4DR) and the serotonin transporter promoter gene (5-HTTLPR), and finding associations with ADHD and temperamental traits.36,37 Collaboration between DBP researchers and geneticists and the use of molecular genetics technology are likely to yield important findings concerning the etiology of developmental-behavioral disorders and normative behavior patterns.

1 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2000. text revision

2 Rivara F, Finberg L. Use of the terms race and ethnicity. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:119.

3 Schonfeld DJ, O’Hare LL, Perrin EC, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of a school-based, multi-faceted AIDS education program in the elementary grades: The impact on comprehension, knowledge and fears. Pediatrics. 1995;95:480-486.

4 Understanding and agreeing to children’s participation in clinical research. In: Field MJ, Behrman RE, editors. Ethical Conduct of Clinical Research Involving Children. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004:146-210.

5 Schweinhart LJ, Montie J, Xiang Z, et al. Lifetime Effects: The High/Scope Perry Preschool Study through Age 40. Ypsilanti, MI: High/Scope Perry Press, 2005.

6 Duggan A, Windham A, McFarlane E, et al. Hawaii’s healthy start program of home visiting for at-risk families: Evaluation of family identification, family engagement, and service delivery. Pediatrics. 2000;105:250-259.

7 DeAngelis C. An Introduction to Clinical Research. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

8 Hulley SB, Cummings SR, Browner WS, et al. Designing Clinical Research: An Epidemiologic Approach, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001.

9 Arcia E, Fernandez MC, Jaquez M. Latina mothers’ stances on stimulant medication: Complexity, conflict, and compromise. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2004;25:311-317.

10 Morse JM, Field PA. Qualitative Research Methods for Health Professionals, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1995.

11 Patton MQ. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods, 3rd ed. London: Sage Publications, 2002.

12 Giacomini MK, Cook DJ. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XXIII. Qualitative research in health care A. Are the results of the study valid? Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 2000;284:357-362.

13 Giacomini MK, Cook DJ. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XXIII. Qualitative research in health care B. What are the results and how do they help me care for my patients? Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 2000;284:478-482.

14 Iannotti RJ, Schneider S, Nansel TR, et al. Self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and diabetes self-management with type 1 diabetes. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2006;27:98-105.

15 Gardner W, Murphy M, Childs G, et al. The PSC-17: A brief Pediatric Symptom Checklist with psychosocial problem subscales. A report from PROS and ASPN. Ambul Child Health. 1999;5:225-236.

16 Stoppelbein L, Greening L, Jordan SS, et al. Factor analysis of the Pediatric Symptom Checklist with a chronically ill pediatric population. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2005;26:349-355.

17 Suen HK. Principles of Test Theories. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum, 1990.

18 Stevens J, Harman JS, Kelleher KJ. Ethnic and regional differences in primary care visits for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2004;25:318-325.

19 Guevara J, Lozano P, Wickizer T, et al. Utilization and cost of health care services for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2001;108:71-78.

20 Barbaresi WJ, Katusic SK, Colligan RC, et al. Long-term stimulant medication treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Results from a population-based study. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2006;27:1-10.

21 Katusic SK, Colligan RC, Barbaresi WJ, et al. Incidence of reading disability in a population-based birth cohort, 1976–1982, Rochester, Minn. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76:1081-1092.

22 Barbaresi WJ, Katusic SK, Colligan RC, et al. The incidence of autism in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1976–1997: Results from a population-based study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:37-44.

23 Rappley MD, Eneli IU, Mullan PB, et al. Patterns of psychotropic medication use in very young children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2002;23:23-30.

24 Cohen J. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 3rd ed. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 2003.

25 Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression, 2nd ed. New York: Wiley, 2000.

26 J-O Kim, Mueller CW. Introduction to Factor Analysis: What It Is and How to Do It. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, 1978.

27 J-O Kim, Mueller CW. Factor Analysis: Statistical Methods and Practical Issues. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, 1978.

28 Loehlin JC. Latent Variable Models: An Introduction to Factor, Path, and Structural Equation Analysis, 4th ed. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 2004.

29 Shafritz KM, Marchione KE, Gore JC, et al. The effects of methylphenidate on neural systems of attention in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1990-1997.

30 Pugh KR, Mencl WE, Jenner AR, et al. Neurobiological studies of reading and reading disability. J Commun Disord. 2001;34:479-492.

31 Newmeyer A, Cecil KM, Schapiro M, et al. Incidence of brain creatine transporter deficiency in males with developmental delay referred for brain magnetic resonance imaging. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2005;26:276-282.

32 Plomin R, DeFries JC, McClearn GE, et al. Behavioral Genetics, 4th ed. New York: Worth Publishing, 2001.

33 Saudino KJ. Behavioral genetics and child temperament. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2005;26:214-223.

34 Wang PP, Woodin MF, Kreps-Falk R, et al. Research on behavioral phenotypes: Velocardiofacial syndrome (deletion 22q11.2). Dev Med Child Neurol. 2000;42:422-427.

35 Goodlin-Jones BL, Tassone F, Gane LW, et al. Autistic spectrum disorder and the fragile X premutation. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2004;25:392-398.

36 Mill J, Curran S, Kent L, et al. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and the dopamine D4 receptor gene: Evidence of association but no linkage in a UK sample. Mol Psychiatry. 2001;6:440-444.

37 Auberbach J, Geller V, Lexer S, et al. Dopamine D4 receptor (D4DR) and serotonin transporter promoter (5-HTTLPR) polymorphisms in the determination of temperament in 2-month-old infants. Mol Psychiatry. 1999;4:369-373.