Regional Anesthesia of the Head and Neck

Intraoral and extraoral regional anesthesia is simple and convenient for everyday use in the emergency department (ED).1 Nerve blocks provide anesthesia to broad areas of distribution on the face with a minimal amount of anesthetic and tissue distortion. Local anesthetic blocks are effective for closing facial lacerations, especially those of the lips, forehead, midface, and ears, places where the swelling caused by local infiltration may be undesirable. Local anesthetic blocks are also effective for the relief of pain, for anesthesia during facial débridement, and for diagnostic purposes.

Regional blocks are also therapeutic for procedural anesthesia and for control of pain in dental emergencies such as toothaches and dry sockets (see Chapter 64). Patients with dental pain who do not obtain relief with a regional dental block most likely do not have pain of dental origin. In cases in which the patient is thought to be seeking drugs, a dental anesthetic block is frequently the treatment of choice as an alternative to narcotics.

Topical anesthetic solutions such as tetracaine-adrenaline-cocaine (TAC) solution are useful for small lacerations of the scalp and face because of the vascularity of these areas. TAC is not to be used on or near the mucous membranes or the eye (see Chapter 29). More extensive discussion of the general complications of local anesthetics and regional anesthesia is provided in Chapters 29 and 32, respectively. Ophthalmologic anesthesia is discussed in Chapter 62, and blocks about the ears and nasal anesthesia are discussed in Chapter 63.

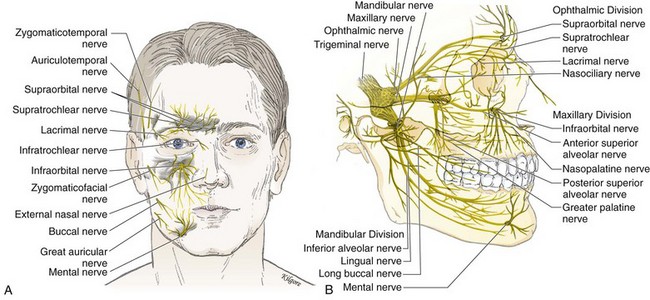

Anatomy of the Fifth Cranial (Trigeminal) Nerve

The fifth cranial nerve, known as the trigeminal nerve, is the sensory nerve to the face (Fig. 30-1A) and the largest of the cranial nerves. It takes its origin from the midbrain and enlarges into the gasserian, or semilunar, ganglion. Each gasserian ganglion supplies one side of the face. The gasserian ganglion is a flat, crescent-shaped structure approximately 10 mm long and 20 mm wide that divides into three branches: the ophthalmic, maxillary, and mandibular nerves (Fig. 30-1B).

Ophthalmic Nerve

1. The medial and lateral branches of the supraorbital nerve, which emerge on the face through the supraorbital notch. These two sensory nerves pierce the frontalis muscle and extend to the lambdoid suture on the back of the skull.

2. The supratrochlear nerve, which provides sensation to the medial aspect of the forehead just above the glabella.

Branches of the ophthalmic nerve provide sensation to the forehead, cornea, upper eyelid, structures in the orbit, and the frontal sinuses.

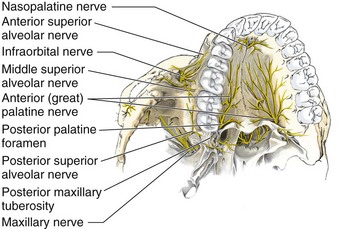

Maxillary Nerve

The anatomy of the maxillary nerve is rather complicated because of its numerous branches. The first branch comprises two short sphenopalatine nerves to the pterygopalatine ganglion, also called the Meckel ganglion or the sphenopalatine ganglion. The next two branches of clinical importance are the nasopalatine and the greater (anterior) palatine nerves. The nasopalatine nerve arises from the pterygopalatine ganglion, courses down along the nasal septum, and is transmitted through the anterior portion of the hard palate by way of the anterior palatine canal. This canal is located in the midline approximately 10 mm palatal to the maxillary central teeth and immediately behind the incisors. The nasopalatine nerve provides sensation to the most anterior portion of the hard palate and the adjacent gum margins of the upper incisors. This nerve is rarely blocked in clinical practice, except in dental operations, because it is quite painful as a result of the tightly bound tissues (Fig. 30-2).

The anterior, or greater, palatine nerve arises from the pterygopalatine ganglion and passes down through the posterior palatine foramen. The posterior palatine foramen is located 10 mm palatal to the third molar and the bicuspid teeth and intermingles with the nasopalatine nerve opposite the cuspid tooth. The greater palatine nerve provides sensation to most of the hard palate, as well as the palatal aspect of the gingiva. It is rarely blocked in the ED (see Fig. 30-2).

The next branch consists of the posterior superior alveolar (PSA) nerve, which courses down the posterior surface of the maxilla for approximately 20 mm, at which point it enters one or several small posterosuperior dental foramina (see Fig. 30-2). This nerve supplies all the roots of the third and second molar teeth and two roots of the first molar tooth. A third branch consists of the middle superior alveolar (MSA) nerve, which branches off about midway within the infraorbital canal and then courses downward in the outer wall of the maxillary sinus (see Fig. 30-2). This nerve supplies the maxillary first and second bicuspid teeth and the mesiobuccal root of the first molar. The last branch consists of the anterior superior alveolar (ASA) nerve, which branches off into the infraorbital canal approximately 5 mm behind the infraorbital foramen, just before the terminal branches of the infraorbital nerve emerge (Fig. 30-2). This nerve descends in the anterior wall of the maxilla to supply the maxillary central, lateral, and cuspid teeth; the labial mucous membrane; the periosteum; and the alveoli on one side of the median line. There is intercommunication among the ASA, MSA, and PSA nerves.

Mandibular Nerve

1. The long buccal nerve branches off just outside the foramen ovale. It passes between the two heads of the external pterygoid muscle and crosses in front of the ramus to enter the cheek through the buccinator muscle, buccal to the maxillary third molar. The buccal nerve supplies sensory branches to the buccal mucous membrane and the mucoperiosteum over the maxillary and mandibular teeth. The cutaneous branch provides sensation to the cheek.

2. The lingual nerve courses forward toward the midline. It runs downward superficially to the internal pterygoid muscle and passes lingual to the apex of the mandibular third molar. It enters the base of the tongue at this point through the floor of the mouth and supplies the anterior two thirds of the tongue, the lingual mucous membrane, and the mucoperiosteum.

3. The largest of the V3 branches is the inferior alveolar nerve. It provides sensation to all the lower teeth, although the central incisors, lateral incisors, and buccal aspect of the molar teeth may receive additional sensory innervation. The nerve descends, covered by the external pterygoid muscle, and passes between the ramus of the mandible and the sphenomandibular ligament to enter the mandibular canal. It is accompanied by the inferior alveolar artery and vein, proceeds along the mandibular canal, and innervates the teeth. At the mental foramen the nerve bifurcates into an incisive branch, which continues forward to supply the anterior teeth. It gives off a side branch, the mental nerve, which exits from the mental foramen to supply the skin. The mental foramen is located approximately between the apices of the lower first and second bicuspids, or premolar teeth. This is a useful site at which to perform a nerve block because the mental nerve provides sensation to the skin of the chin and the mucous membrane of the lower lip.

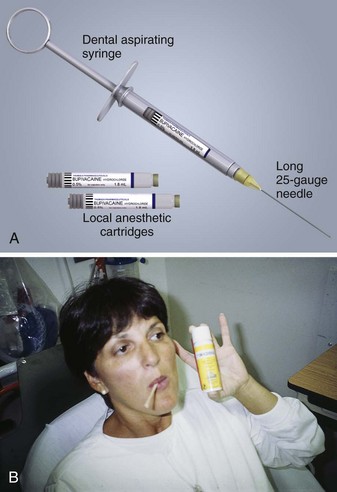

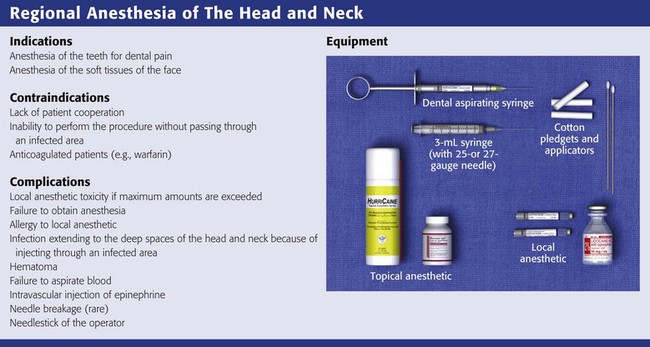

Equipment for Dental and Cranial Nerve Blocks

Extraoral injections can be done easily with a 3-mL Luer-Lok syringe and a  -inch, 25- to 27-gauge needle. A needle no smaller than 27 gauge is recommended for deep block techniques because of the inability to perform aspiration. Generally, a long needle is used for nerve blocks and a short needle is used for infiltration. Intraoral local anesthesia can also be conveniently administered with a dental aspirating syringe, which uses a Carpule cartridge of anesthetic along with a disposable needle (Fig. 30-3A). Dental aspirating syringes are not mandatory for intraoral local anesthesia but they make the procedure simpler, particularly when aspirating. Other adjuncts that are helpful in the administration of intraoral anesthesia include topical mucosal anesthetic agents such as gels or sprays because they can make the injection nearly painless (Fig. 30-3B). First swab the gauze-dried mucosa with a topical agent or have the patient hold cotton swabs soaked in the agent to the anticipated injection site, and wait for 1 to 3 minutes. Excellent topical anesthesia of the mucous membranes can be achieved after 2 minutes by applying a gel mixture of a topical anesthetic consisting of 10% lidocaine, 10% prilocaine and 4% tetracaine (Profound, Steven’s Pharmacy, Costa Mesa, CA; www.stevensrx.com).

-inch, 25- to 27-gauge needle. A needle no smaller than 27 gauge is recommended for deep block techniques because of the inability to perform aspiration. Generally, a long needle is used for nerve blocks and a short needle is used for infiltration. Intraoral local anesthesia can also be conveniently administered with a dental aspirating syringe, which uses a Carpule cartridge of anesthetic along with a disposable needle (Fig. 30-3A). Dental aspirating syringes are not mandatory for intraoral local anesthesia but they make the procedure simpler, particularly when aspirating. Other adjuncts that are helpful in the administration of intraoral anesthesia include topical mucosal anesthetic agents such as gels or sprays because they can make the injection nearly painless (Fig. 30-3B). First swab the gauze-dried mucosa with a topical agent or have the patient hold cotton swabs soaked in the agent to the anticipated injection site, and wait for 1 to 3 minutes. Excellent topical anesthesia of the mucous membranes can be achieved after 2 minutes by applying a gel mixture of a topical anesthetic consisting of 10% lidocaine, 10% prilocaine and 4% tetracaine (Profound, Steven’s Pharmacy, Costa Mesa, CA; www.stevensrx.com).

Figure 30-3 A, Local anesthesia—basic setup for intraoral application using an aspirating dental syringe. B, Topical mucosal anesthesia can make the injection nearly painless. Swab the gauze-dried mucosa with the topical agent or have the patient hold cotton swabs soaked in the agent, and wait for 1 to 3 minutes. Benzocaine can be used as a topical anesthetic (shown here). However, excellent topical anesthesia of mucous membranes can be obtained after 2 minutes by applying a gel mixture of a topical anesthetic consisting of 10% lidocaine, 10% prilocaine, and 4% tetracaine. (Profound, Steven’s Pharmacy, Costa Mesa, CA. Available at www.stevensrx.com).

General Recommendations

Use needles no smaller than 27 gauge for block techniques because a higher-gauge needle makes aspiration difficult and can thus result in inadvertent intravascular injection. Intravascular epinephrine, though used in small doses, may produce systemic symptoms (anxiety, tachycardia), as well as painful vasospasm if injected intraarterially, but the amount of local anesthetic is generally inconsequential.2

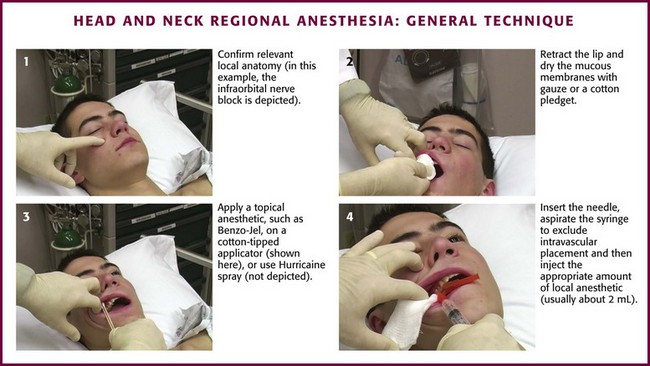

Technique

Most patients fear dental blocks greatly, and the anxiety and pain may be lessened considerably with the use of topical anesthetics applied to the mucous membranes before injection (Fig 30-4, step 3). It is important to dry the injection site thoroughly with gauze before the injection (see Fig 30-4, step 2) because copious saliva will wash the anesthetic away prematurely. Coat a cotton-tipped applicator generously with 20% benzocaine (Hurricaine, Beutlich, Inc., Niles, IL) or 5% to 10% lidocaine so that the area of injection is completely covered. Allow the patient to hold the cotton swab in place. The area will be anesthetized in 2 to 3 minutes. Use concentrated topical anesthetics because poor results are obtained with weaker preparations such as 2% viscous lidocaine. Cocaine (4%) is another acceptable topical anesthetic.

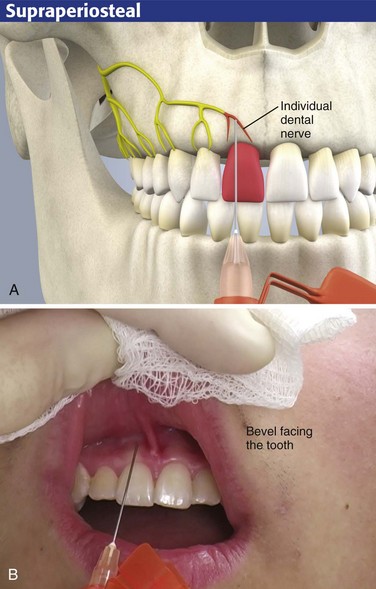

Supraperiosteal Infiltration

The most common technique for intraoral local anesthesia of individual teeth is supraperiosteal infiltration (Fig. 30-5). This technique can provide complete relief of a toothache. Select the area to be anesthetized and dry it with gauze. Apply a topical anesthetic, such as 20% benzocaine or 5% lidocaine ointment, as described. Ask the patient to close the jaw slightly and relax the facial musculature. Grasp the mucous membrane of the area with a piece of gauze. Pull the gauze outward and downward in the maxilla and outward and upward in the mandible to extend the mucosa fully and to delineate the mucobuccal fold. Puncture the mucobuccal fold with the bevel of the needle facing the tooth. Aspirate the area and deposit approximately 1 to 2 mL of local anesthetic (2% lidocaine should be used here) at the apex (area of the root tip) of the involved tooth (see Fig. 30-5). It is helpful to place a finger against the outer aspect of the lip overlying the injection site. Apply firm and steady pressure against the lip and slowly inject the local anesthetic into the supraperiosteal site. This helps prevent ballooning of the lip.

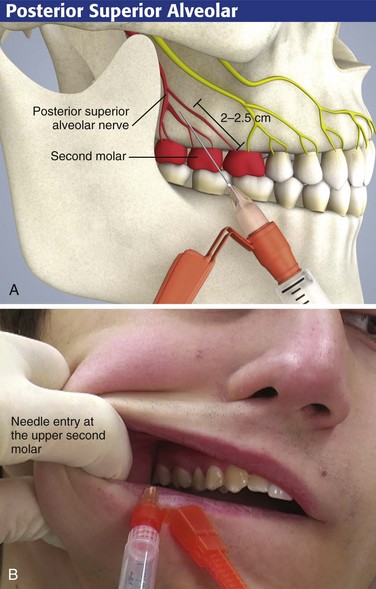

Posterior or Superior Alveolar Nerve Block

Use the PSA block to anesthetize the maxillary molar teeth (Fig. 30-6). On occasion, the maxillary first molar is not completely anesthetized by this technique alone and may require an additional block (discussed subsequently). The landmarks for this technique are the posterior-lateral portion of the maxillary tuberosity and the second molar.

Intraoral Approach

For the intraoral approach, apply a topical anesthetic on a cotton-tipped swab to the gauze-dried mucosa for 60 to 90 seconds before introducing the needle for the nerve block.2 With the patient’s mouth half-open and the jaw facing the operator, retract the cheek laterally. Make the puncture in the mucosal reflection just distal to the distal buccal root of the upper second molar (Fig. 30-6B). Direct the needle toward the maxillary tuberosity (i.e., upward, backward, and inward) and then along the curvature of the maxillary tuberosity to a depth of approximately 2 to 2.5 cm. On reaching this depth, aspirate with the needle and inject 2 to 3 mL of anesthetic solution.

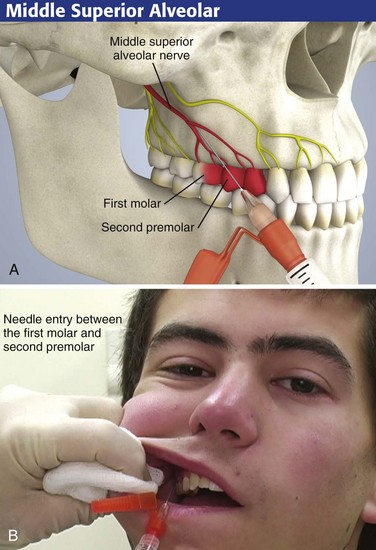

MSA Nerve Block

Use the MSA block to anesthetize the mesiobuccal root of the maxillary first molar, which will provide complete anesthesia of the tooth (Fig. 30-7). The landmark for this procedure is the junction between the second premolar and first molar.

Intraoral Approach

Apply a topical anesthetic on a cotton-tipped swab to gauze-dried mucosa for 60 to 90 seconds before introducing the needle for the nerve block. Retract the cheek laterally and make a puncture in the mucosal reflection adjacent to the mesiobuccal root area of the first molar (the space between the second premolar and the first molar). Direct the needle at a 45-degree angle (see Fig. 30-7A). When the correct location has been determined and aspiration has been performed, inject 2 to 3 mL of anesthetic solution. Massage the tissue for 10 to 15 seconds after the injection to hasten the onset of anesthesia.

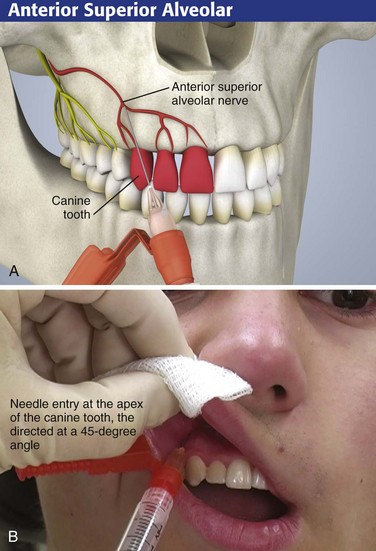

ASA Nerve Block

Intraoral Approach

For the intraoral approach, apply a topical anesthetic on a cotton-tipped swab to gauze-dried mucosa for 60 seconds before introducing the needle for the nerve block. Ask the patient to close the jaw slightly to relax the upper lip. Retract the lip anteriorly and make the puncture in the mucosal reflection at the apex of the canine tooth while directing the needle at a 45-degree angle (see Fig. 30-8B). When the correct location has been determined and aspiration has been performed, inject 2 mL of anesthetic solution. Massage the tissue for 10 to 15 seconds after the injection to hasten the onset of anesthesia.

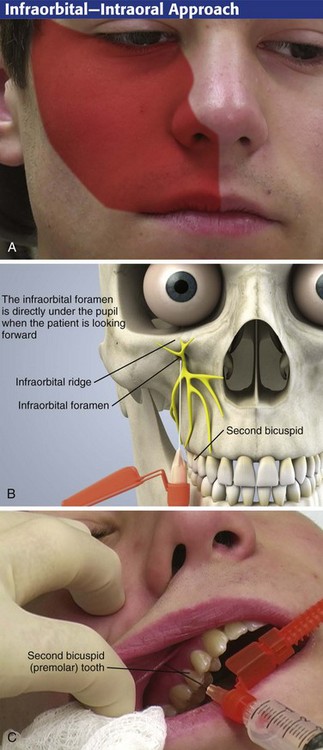

Infraorbital Nerve Block

An infraorbital nerve block can be used to anesthetize the midface region (Fig. 30-9A). A solution of local anesthetic deposited adjacent to the infraorbital foramen anesthetizes not only the middle and superior alveolar nerves but also the main trunk of the infraorbital nerve, which innervates the skin of the upper lip, the skin of the nose, and the lower eyelid. The nasal mucosa is not anesthetized with this technique.

The infraorbital foramen is difficult to palpate extraorally and almost impossible to feel in the presence of facial swelling. It is found on the inferior border of the infraorbital ridge on a vertical (sagittal) line with the pupil when the patient stares straight ahead. Although one volunteer study found similar patient pain scale scores and overall preference in subjects undergoing both intraoral and extraoral approaches, the intraoral approach seemed to provide nearly twice the duration of anesthesia.3

Intraoral Approach

Apply a topical anesthetic on a cotton-tipped swab to gauze-dried mucosa for 60 to 90 seconds before introducing the needle for the nerve block. When performing the intraoral approach, keep the palpating finger in place over the inferior border on the infraorbital rim. Retract the cheek as for the supraperiosteal injection, and make the puncture in the mucosa opposite the upper second bicuspid (premolar tooth) approximately 0.5 cm from the buccal surface (Fig. 30-9B). Direct the needle parallel to the long axis of the second bicuspid until it is palpated near the foramen, at a depth of approximately 2.5 cm. If the entry is too acute, one may encounter the malar eminence before approaching the infraorbital foramen. In addition, if the needle is extended too far posteriorly and superiorly, the orbit may be entered. Halt the procedure if you are unsure of the location of the needle or if the patient is not cooperating.

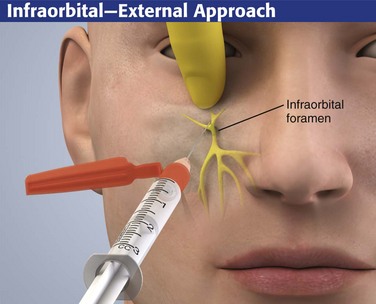

Extraoral Approach

The infraorbital foramen can also be approached from an extraoral route (Fig. 30-10). The extraoral approach requires external preparation of the skin. With the extraoral approach use similar landmarks to locate the infraorbital foramen. The needle can be felt as it passes through the skin, the subcutaneous tissue, and the quadratus labii superioris muscle. After injection, firmly massage the infiltrated tissue for 10 to 15 seconds. It is usually visibly swollen. Place a finger under the eye to limit eye edema.

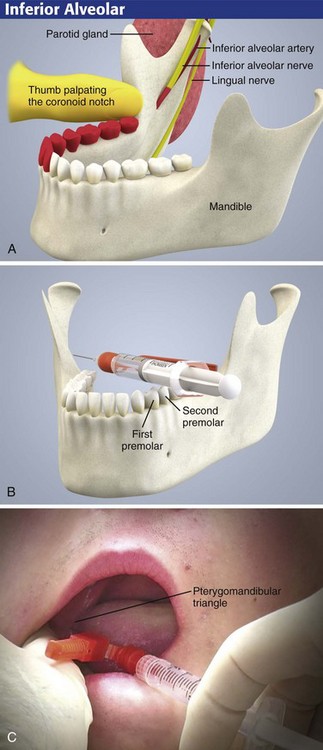

Inferior Alveolar Nerve Block

Anatomy

First review the anatomy of the region (Fig. 30-11A). The patient can be seated either in a dental chair or upright with the occiput firmly against the back of the stretcher so that when the mouth is opened, the body of the mandible is parallel to the floor. Despite the use of topical anesthesia, be ready for an unexpected quick jerk of the head when an anxious patient first feels the needle. Stand on the side opposite the one being injected.

The technique first involves palpation of the retromolar fossa with the index finger or thumb. With this maneuver, the greatest depth of the anterior border of the ramus of the mandible (the coronoid notch) may be identified (Fig. 30-11A). With the thumb in the mouth resting in the retromolar fossa and the index finger placed externally behind the ramus at the same height as the thumb (Fig 30-12), the tissues are retracted toward the buccal (cheek) side, and the pterygomandibular triangle is visualized (Fig. 30-11C). This technique also moves the operator’s finger safely away from the tip of the needle.

Approach

Coat the gauze-dried mucosa over the area to be injected with a topical anesthetic, as described previously. When topical anesthesia has been achieved, hold the syringe parallel to the occlusal surfaces of the teeth and angled so that the barrel of the syringe lies between the first and second premolars on the opposite side of the mandible (Fig. 30-11B). Failing to appreciate this required angle is the most common reason for failure of this nerve block. If a large-barrel syringe is used, the corner of the mouth may hamper efforts to obtain the proper angle. Facilitate the angle by carefully bending the 25-gauge needle about 30 degrees (see Fig. 30-12). Puncture inside the triangle at a point 1 cm above the occlusal surface of the molars. If the needle enters too low (e.g., at the level of the teeth), the anesthetic will be deposited over the bony canal and prominence (lingula) that house the mandibular nerve and not over the nerve itself.

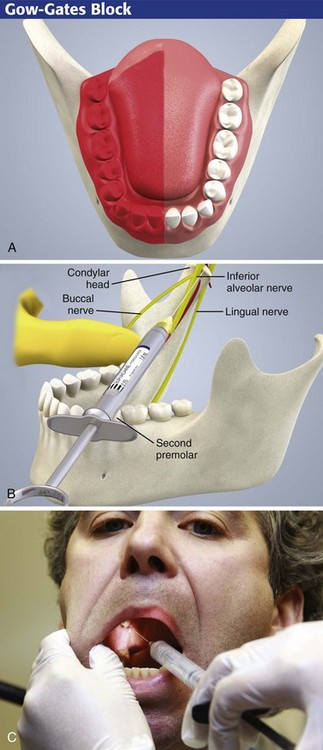

Gow-Gates Block

The inferior alveolar nerve block may be unsuccessful because of deposition of anesthetic in a plane medial to the lingula. In addition, the traditional technique involves depositing additional anesthetic for the long buccal nerve. First introduced in the 1970s, the Gow-Gates mandibular block is also an acceptable technique for achieving mandibular anesthesia, especially if traditional approaches fail (Fig. 30-13). The Gow-Gates approach involves the deposition of anesthetic at the lateral aspect of the anterior condylar head below the insertion of the lateral pterygoid muscle, and it uses extraoral landmarks (tragus of the ear and corner of the mouth).4 The area is much less vascular than the area near the lingula. For this reason, epinephrine mixed with the local anesthetic is not necessary.

Approach

Ask the patient to open the mouth widely (Fig. 30-13C). Place a finger inferior to the tragus of the ear as the landmark for the lateral aspect of the anterior condyle (which is now sitting at the eminence). Insert the needle opposite the second molar with the barrel of the syringe between the opposite lower premolars and the corner of the mouth (similar to the inferior alveolar approach). With this plane maintained, advance the needle until it reaches the condylar neck. Withdraw the needle, aspirate, and inject 1 to 2 mL of anesthetic.4,5

Complications

The positive vascular aspiration rate with the Gow-Gates procedure is reported to be 1.6%, as compared with a range of positive aspiration with the conventional inferior alveolar technique of 3.5% to 22%.6 If the needle is directed more toward the medial aspect of the anterior condylar process, the needle is then in the proximity of the pterygoid plexus of veins and the sympathetic plexus of the internal carotid artery. If the sympathetic plexus is anesthetized, Horner’s syndrome will temporarily develop.

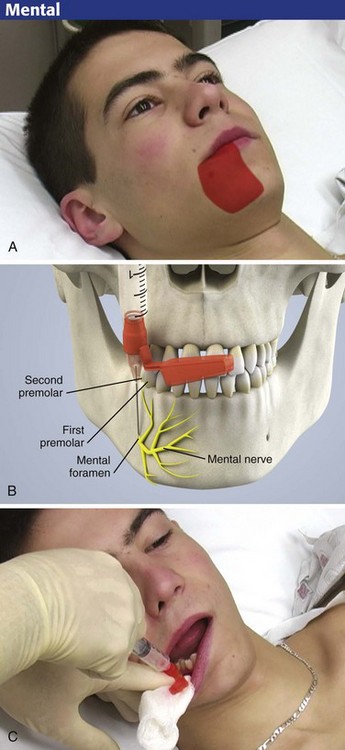

Mental Nerve Block

Anatomy

The mental nerve is a continuation of the inferior alveolar nerve and innervates the mucosa and skin of the lower lip on the ipsilateral side of the mandible, with limited crossover of midline fibers. The nerve emerges from the mental foramen below the second premolar. Lacerations of the lower lip can be repaired with this block (Fig. 30-14).

Approaches

Like the infraorbital nerve, block the mental nerve via an intraoral or extraoral approach. Syverud and colleagues found that volunteers who received intraoral topical anesthetic followed by an intraoral injection considered the technique to be less painful than the extraoral approach.7 Before using either approach, identify the mental foramen by palpation about 1 cm inferior and anterior to the second premolar. It is usually best to locate the foramen with a gloved finger placed in the labial area over the mandible. Generally, the foramen will be just medial to the pupil of the eye (while the patient stares straight ahead) along a sagittal plane. The intraoral approach is demonstrated in Figure 30-15.

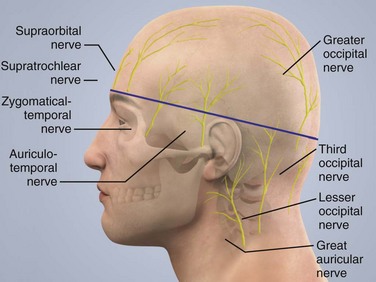

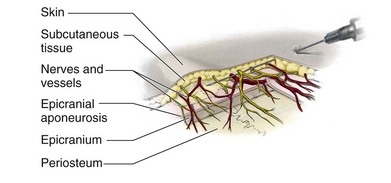

Scalp Block

Anatomy

As shown in Figure 30-16, the scalp receives its nerve supply from branches of the trigeminal nerve (fifth cranial nerve) and the cervical plexus. The forehead is supplied by the supraorbital and supratrochlear nerves. Both nerves are branches of the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve. The temporal region receives its nerve supply from the zygomaticotemporal (a V2 branch nerve), temporomandibular, and auriculotemporal nerves (V3 branch nerves).

The posterior aspect of the scalp is innervated by the great auricular and the greater, lesser, and least (third) occipital nerves. The nerves that supply the posterior aspect of the scalp originate from the cervical plexus. All the nerves become superficial above a line drawn from the upper border of the external ear to the occiput and the eyebrows and converge toward the vertex of the scalp (see Fig. 30-16).

Topographically, the nerves and vessels of the scalp are located in subcutaneous tissue above the epicranial aponeurosis. From this level they divide into small branches that extend to the deeper layers (epicranium and periosteum) (Fig. 30-17).8,9

Approaches

Prepare the skin with an antiseptic solution, and raise a skin wheal at any point along the clipped skin with a 1.3-cm ( -inch), 25-gauge needle. Insert a 7.6-cm (3-inch), 22-gauge needle through the skin wheal and into subcutaneous tissue. Advance it along the scalp circumferentially following the previously clipped area. Inject 0.5% to 1% lidocaine or 0.125% to 0.25% bupivacaine with epinephrine (1 : 200,000). Add epinephrine to the local anesthetic agent to provide vasoconstriction and prevent excessive blood loss and absorption of local anesthetic. The total dose of the local anesthetic agents should not exceed the recommended dose for that particular agent (see Chapter 29). Inject some local anesthetic solution into the temporalis muscle to prevent contraction of the muscle during the primary procedure if necessary.

-inch), 25-gauge needle. Insert a 7.6-cm (3-inch), 22-gauge needle through the skin wheal and into subcutaneous tissue. Advance it along the scalp circumferentially following the previously clipped area. Inject 0.5% to 1% lidocaine or 0.125% to 0.25% bupivacaine with epinephrine (1 : 200,000). Add epinephrine to the local anesthetic agent to provide vasoconstriction and prevent excessive blood loss and absorption of local anesthetic. The total dose of the local anesthetic agents should not exceed the recommended dose for that particular agent (see Chapter 29). Inject some local anesthetic solution into the temporalis muscle to prevent contraction of the muscle during the primary procedure if necessary.

Colley and Heavner demonstrated that when bupivacaine is used, peak plasma local anesthetic concentrations occur within 10 to 15 minutes after injection.10 Thus, the first 10- to 15-minute period after the injection is the most critical period to monitor for local anesthetic toxicity. Colley and Heavner also found that despite the scalp’s high vascularity, absorption of local anesthetics from the scalp is not excessive.10 Because that the toxic plasma threshold for bupivacaine is 4 µg/mL, these concentrations suggest that a scalp block using bupivacaine has a wide margin of safety, even without the use of epinephrine. When epinephrine is used with bupivacaine, its effect on absorption becomes more pronounced with concentrations of 0.125% than with 0.25%. This is probably because at low concentrations (0.125%), bupivacaine has a vasoconstrictor property.11

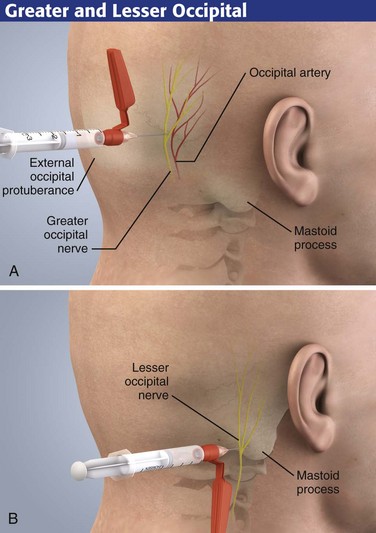

Greater and Lesser Occipital Nerve Block

This relatively simple block may be useful in the ED for treating occipital neuralgia and tension headaches. For occipital neuritis, a long-acting corticosteroid such as methylprednisolone (20 to 40 mg) may be combined with the local anesthetic (see Chapter 52).12

Anatomy

The posterior aspect of the head is supplied by the posterior rami of the cervical nerves. Two important branches of these nerves are the greater and lesser occipital nerves. The greater occipital nerve becomes superficial on each side at the inferior border of the obliquus capitis inferior muscle and runs superiorly toward the vertex over this muscle. The nerve is located medial to the occipital artery. The lesser occipital nerve is located approximately 2.5 to 3.5 cm lateral and 1 to 2 cm caudal to the greater occipital nerve (see Fig. 30-16).

Approach

First, palpate the occipital artery. Next, attach a 3.8-cm, 23- to 25-gauge needle to a syringe containing 5 mL of local anesthetic. Insert the needle into the skin (Fig. 30-18A). After obtaining paresthesia at the vertex, inject 5 mL of local anesthetic solution. Block the lesser occipital nerve with a fanlike injection of a local anesthetic solution, 2.5 to 3.5 cm lateral and 1 cm caudal to the point described for the greater occipital nerve (Fig. 30-18B).

Ophthalmic (V1) Nerve Block

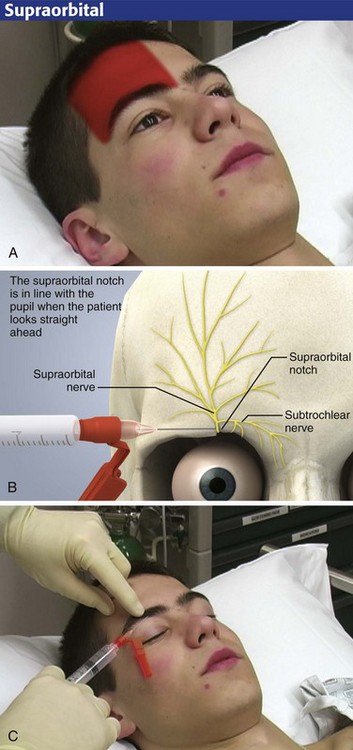

The lateral and medial branches of the supraorbital, supratrochlear, and infratrochlear nerves may be blocked by percutaneous local injection at the point where they emerge from the superior aspect of the orbit. Anesthesia of the forehead and scalp is achieved as far posteriorly as the lambdoid suture. Although anesthesia for suturing lacerations of the forehead and scalp is easily achieved, the nerve block may also be used for débridement or topical treatment of burns or abrasions and for delicate lacerations of the upper eyelid (Fig. 30-19). Such anesthesia is ideal for removing small pieces of glass embedded in the forehead from a windshield injury.

Anatomy

The subtle supraorbital notch, which is in line with the pupil (when the patient is staring straight ahead), can be palpated along the superior orbital rim (Fig. 30-20B). This landmark is the site of injection for blockade of the supraorbital nerves. The supratrochlear nerve is found 0.5 to 1.0 cm medial to the notch. The infratrochlear nerve is not usually blocked but is found in the most medial aspect of the superior orbital rim. If the anesthetic is placed on the forehead proper, this block may not produce complete anesthesia of the skin of the upper eyelid if the sensory branches to the eyelid are given off before the supraorbital nerve traverses the forehead.

Approach

With the patient in the supine position, raise a skin wheal. Paresthesias in the form of an electric shock sensation over the forehead will ensure a successful nerve block. Inject 1 to 3 mL of anesthetic in the area of the supraorbital notch (Fig. 30-20C). Hold a finger or a roll of gauze firmly under the orbital rim to avoid ballooning of anesthetic into the upper eyelid.

Conclusion

Nerve blocks about the head and neck are relatively painless when done carefully and slowly after topical mucosal anesthesia (for intraoral approaches) or local skin anesthesia (for extraoral blocks and approaches). Patients who appear anxious may benefit from sedation before attempting these blocks (see Chapter 33). These blocks should not be attempted on an uncooperative patient.

References

1. Malamed SF, ed. Handbook of Local Anesthesia with Malamed’s Administration DVD Package, 5th ed, Chicago: Mosby, 2005.

2. Webber, B, Orlansky, H, Lipton, C, et al. Complications of an intra-arterial injection from an inferior alveolar nerve block. J Am Dent Assoc. 2001;132:1702–1704.

3. Lynch, MT, Syverud, SA, Schwab, RA, et al. Comparison of intraoral and percutaneous approaches for infraorbital nerve block. Acad Emerg Med. 1994;1:514.

4. Norton, NS. Mandibular injections. In: Netter’s Head and Neck Anatomy for Dentistry. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007:572–574.

5. Kafalian, MC, Gow-Gates, GAE, Saliba, GJ. The Gow-Gates technique for mandibular block anesthesia. Anesth Prog. 1987;34:142–149.

6. Watson, JE, Gow-Gates, GA. Incidence of positive aspiration in the Gow-Gates mandibular block. Anesth Pain Control Dent. 1992;1(2):73–76.

7. Syverud, SA, Jenkins, JM, Schwab, RA, et al. A comparative study of the percutaneous versus intraoral technique for mental nerve block. Acad Emerg Med. 1994;1:509.

8. Murphy, TM. Somatic blockade. In: Cousins MJ, Bridenbaugh PO, eds. Neural Blockade in Clinical Anesthesia and Management of Pain. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1980:410.

9. Bohm, E. Local anesthesia of the scalp. In: Eriksson E, ed. Illustrated Handbook in Local Anesthesia. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1980:25.

10. Colley, PS, Heavner, JE. Blood levels of bupivacaine after injection into the scalp with and without epinephrine. Anesthesiology. 1981;54:81.

11. Alps, C, Reynolds, F. The effect of concentration on vasoactivity of bupivacaine and lignocaine. Br J Anaesth. 1976;48:1171.

12. Jenkner, FL. Greater (and lesser) occipital nerve block. In: Jenkner FL, ed. Peripheral Nerve Block. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1977:100.

-inch needle is bent 30 degrees with the needle guard.

-inch needle is bent 30 degrees with the needle guard.

-inch), 25- or 27-gauge needle on a 3-mL syringe.

-inch), 25- or 27-gauge needle on a 3-mL syringe.