Chapter 151 Reactive and Postinfectious Arthritis

The role of infectious agents in the pathophysiology of arthritis is a topic of intense study. In addition to causing arthritis by means of direct infection (i.e., septic arthritis; Chapter 677), infection can lead to the generation and deposition of immune complexes as well as antibody or T cell–mediated cross-reactivity with self. Evidence continues to grow that microorganisms also play a role in the development of classic autoimmune diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus and juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Reactive and postinfectious arthritis are defined as joint inflammation due to a sterile inflammatory reaction following a recent infection. For historical reasons, we use reactive arthritis to refer to arthritis that occurs following enteropathic or urogenital infections and postinfectious arthritis to describe arthritis that occurs after infectious illnesses not classically considered in the reactive arthritis group, such as infection with group A streptococcus or viruses. In some cases, nonviable components of the initiating organism have been demonstrated in affected joints, and the presence of viable, yet nonculturable, bacteria within the joint remains an area of investigation.

The course of reactive arthritis is variable and may remit or progress to a chronic spondyloarthritis including ankylosing spondylitis (Chapter 150). In postinfectious arthritis, the pain or joint swelling is usually transient, lasting less than 6 wk, and does not share the typical spondyloarthritis pattern. The distinction between postinfectious arthritis and reactive arthritis is not always clear, either clinically or in terms of pathophysiology.

Pathogenesis

Reactive arthritis typically follows enteric infection with Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia enterocolitica, Campylobacter jejuni, Cryptosporidium parvum, or Giardia intestinalis, or genitourinary tract infection with Chlamydia trachomatis or Ureaplasma. Though similar in some respects to reactive arthritis, acute rheumatic fever caused by group A streptococcus (Chapter 176.1), arthritis associated with infective endocarditis (Chapter 431), and the tenosynovitis associated with Neisseria gonorrhoeae are considered later.

Clinical Manifestations and Differential Diagnosis

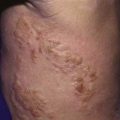

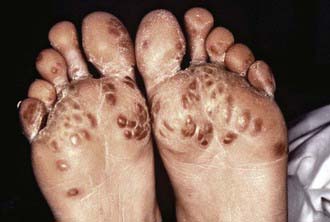

Symptoms of reactive arthritis present approximately 2-4 wk following infection. The classic triad of arthritis, urethritis, and conjunctivitis (formerly referred to as Reiter syndrome) is relatively uncommon in children. The arthritis is typically oligoarticular, with a lower extremity predilection. Dactylitis may occur, and enthesitis (Fig. 151-1) is common (Chapter 150). Cutaneous manifestations can occur and may include circinate balanitis, ulcerative vulvitis, oral lesions, and keratoderma blennorrhagica, which is similar in appearance to pustular psoriasis (Fig. 151-2). Systemic symptoms may include fever, malaise, and fatigue. Early in the disease course, markers of inflammation—erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), and platelets—may be markedly elevated.

Figure 151-1 Enthesitis—swelling of the posterior aspect of the left heel and lateral aspect of the ankle.

(Courtesy of Nora Singer, Case Western Reserve University and Rainbow Babies’ Hospital.)

Figure 151-2 Keratoderma blennorrhagica.

(Courtesy of Dr. M.F. Rein and The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Public Health Image Library, 1976. Image #6950.)

Familiarity with other causes of postinfectious arthritis is vital when a diagnosis of reactive arthritis is being considered. Numerous viruses are associated with postinfectious arthritis (Table 151-1) and may result in particular patterns of joint involvement. Rubella and hepatitis B virus typically affect the small joints, whereas mumps and varicella often involve large joints, especially the knees. The hepatitis B arthritis–dermatitis syndrome is characterized by urticarial rash and a symmetric migratory polyarthritis resembling that of serum sickness. Rubella-associated arthropathy may follow natural rubella infection and, infrequently, rubella immunization. It typically occurs in young women, with an increased frequency with advancing age, and is uncommon in preadolescent children and in males. Arthralgia of the knees and hands usually begins within 7 days of onset of the rash or 10-28 days after immunization. Parvovirus B19, which is responsible for erythema infectiosum (fifth disease), can cause arthralgia, symmetric joint swelling, and morning stiffness, particularly in adult women and less frequently in children. Arthritis occurs occasionally during cytomegalovirus infection and may occur during varicella infections but is rare after Epstein-Barr virus infection. Varicella may also be complicated by suppurative arthritis, usually secondary to group A streptococcus infection. HIV is associated with an arthritis that resembles psoriatic arthritis more than juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA).

Table 151-1 VIRUSES ASSOCIATED WITH ARTHRITIS

Adapted from Cassidy JT, Petty RE: Infectious arthritis and osteomyelitis. In Textbook of pediatric rheumatology, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2005, WB Saunders.

Post-streptococcal arthritis is a postinfectious arthritis that may follow infection with either group A or group G streptococcus. It is typically oligoarticular, affecting lower extremity joints, and mild symptoms can persists for months. Post-streptococcal arthritis differs from rheumatic fever, which typically follows a course with painful migratory polyarthritis of brief duration. Because valvular lesions have occasionally been documented by echocardiography after the acute illness, some clinicians consider post-streptococcal arthritis to be an incomplete form of acute rheumatic fever (Chapter 176.1). Certain HLA-DRB1 types may predispose children to development of either post-streptococcal arthritis (HLA-DRB1*01) or acute rheumatic fever (HLA-DRB1*16).

Transient synovitis (toxic synovitis), another form of post-infectious arthritis, typically affects the hip, often after an upper respiratory tract infection (Chapter 670.2). Boys from 3 to 10 yr of age are most commonly affected and have acute onset of severe pain in the hip, with referred pain to the thigh or knee, lasting approximately 1 wk. The ESR and white blood cell count are usually normal. Radiologic or ultrasound examination may confirm widening of the joint space secondary to effusion. Aspiration of joint fluid is often necessary to exclude septic arthritis and results in dramatic clinical improvement. The trigger is presumed to be viral, although responsible microbes have not been identified.

Diagnosis

Because the preceding infection can be remote or mild and often not recalled by the patient, it is also important to rule out other causes of arthritis. Acute arthritis affecting a single joint suggests septic arthritis, mandating joint aspiration; osteomyelitis may cause pain and an effusion in an adjacent joint but is more often associated with focal bone pain over the site of infection. The diagnosis of postinfectious arthritis is often established by exclusion, after the arthritis has resolved. Arthritis associated with gastrointestinal symptoms or abnormal liver function test results may be triggered by infectious or autoimmune hepatitis. Arthritis or spondyloarthritis may occur in children with inflammatory bowel disease, such as Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis (Chapter 328). When two or more blood cell lines progressively decrease in concentration in a child with arthritis, parvovirus infection, macrophage activation (hemophagocytic) syndrome, and leukemia should be strongly considered. Persistent arthritis (>6 wk) suggests the possibility of a chronic rheumatic disease, including JIA (Chapters 149 and 150) and systemic lupus erythematosus.

Complications and Prognosis

Postinfectious arthritis following viral infections usually resolves without complications unless it is associated with involvement of other organs, such as encephalomyelitis. Children with reactive arthritis after enteric infections occasionally experience inflammatory bowel disease months to years after onset. Both uveitis and carditis have been reported in children diagnosed with reactive arthritis. Reactive arthritis, especially after bacterial enteric infection or genitourinary tract infection with Chlamydia trachomatis, has the potential for evolving to chronic arthritis, particularly spondyloarthritis (Chapter 150). The presence of HLA-B27 or significant systemic features increases the risk of chronic disease.

Astrauskiene D, Bernotiene E. New insights into bacterial persistence in reactive arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2007;25:470-479.

Cann MP, Sive AA, Norton RE, et al. Clinical presentation of rheumatic fever in an endemic area. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95:455-457.

Colmegna I, Espinoza LR. Recent advances in reactive arthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2005;7:201-207.

Dajani A, Taubert K, Ferrieri P, et al. Treatment of acute streptococcal pharyngitis and prevention of rheumatic fever: a statement for health professionals. Pediatrics. 1995;96:758-764.

Franssila R, Hedman K. Viral causes of arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2006;20:1139-1157.

Gerard HC, Wang Z, Wang GF, et al. Chromosomal DNA from a variety of bacterial species is present in synovial tissue from patients with various forms of arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:1689-1697.

Hannu T, Inman R, Granfors K, et al. Reactive arthritis or post-infectious arthritis? Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2006;20:419-433.

Inman RD. Mechanisms of disease: Infection and spondyloarthritis. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2006;2:163-169.

Kvien TK, Vischer T, Bardin T, et al. EULAR: Three month treatment of reactive arthritis with azithromycin: A EULAR double blind, placebo controlled study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:1113-1119.

Leirisalo-Repo M. Early arthritis and infection. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2005;17:285-288.

Mackie SL, Keat A. Poststreptoccal reactive arthritis: what is it and how do we know? Rheumatology. 2005;43:949-954.

Mertz AK, Ugrinovic S, Lauster R, et al. Characterization of the synovial T cell response to various recombinant yersinia antigens in Yersinia enterocolitica triggered reactive arthritis: heat-shock protein 60 drives a major immune response. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:315-326.

Petty RE, Tingle AJ. Arthritis and viral infection. J Pediatr. 1988;113:948-949.

Townes JM, Deodhar AA, Laine ES, et al. Reactive arthritis following culture-confirmed infections with bacterial enteric pathogens in Minnesota and Oregon: a population-based study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1689-1696.