Chapter 207 Rationale for Practice Hygiene

Coding, Reimbursement, and Nomenclature

Development of Diagnosis Coding

However, it was not until the sixth revision during the International Health Conference in 1946 that a classification of causes of morbidity was also included. This conference is credited with the development of international cooperation in health statistics, linking national statistical institutions with the World Health Organization (WHO). The current classification, entitled the International Classification of Diseases-ninth revision-Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM), represents the efforts of the WHO in 1975.1 Modifications included the creation of fourth and fifth digits to allow two additional levels of subclassification to the previous three-digit system, as well as an independent four-digit system to classify the histopathology of neoplasms. This internationally used classification scheme provides a uniform method for tracking morbidity data and preparing claims for reimbursement.

Although primarily used for diagnostic coding, ICD-9-CM also contains codes assigned to procedures and complications.2 More than 8000 diagnostic codes, covering the entire scope of clinical diseases, represent the most commonly used subset by physicians. The first section, including codes from 001.0 to 999.9, is divided into 17 classifications of diseases and injuries, including infectious and parasitic diseases; neoplasms; diseases defined by body systems; congenital anomalies; symptoms, signs, and ill-defined conditions; and injuries and poisonings. The second section, consisting of codes from V01.0 to V82.9, describes the reasons for a patient visit other than disease or injury. V codes may be used when reporting preventive medical treatments, physical examination, postoperative follow-up examinations, physical therapy, radiographs, and laboratory tests.

Guidelines implemented by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) require association of each service provided with an ICD-9-CM code, starting with the primary diagnosis.2 The chosen diagnostic code should be of the highest degree of specificity, utilizing fourth and fifth digits when applicable. Additional secondary and tertiary diagnoses should also be included if relevant to the service provided. Although coexisting conditions affecting the patient’s treatment should also be included, diagnoses that are no longer applicable (as the patient’s circumstances change) should be eliminated. Services provided for reasons other than disease or injury, such as well-baby office visits, should be identified with the appropriate V code.

The WHO planned to replace ICD-9-CM with ICD-10-CM by 1998.3 However, although ICD-10-CM has been drafted and implemented in many regions, application in the United States has been delayed. Unlike ICD-9-CM, ICD-10-CM contains only diagnosis and no procedural codes. Some of the differences include a vastly increased number of categories of codes (2033 as compared to 855 in ICD-9-CM); a different format (a six-digit alphanumeric system with the letter at the beginning and the decimal point in the middle [e.g., C50.333]); and more specificity of some codes, sometimes including severity rating and/or sidedness. Costs associated with the retooling of computers and educating staff about this new system have been the main reasons cited for the delayed implementation. The potential for a greater degree of specificity places an additional burden on documentation, which must be examined to ensure that it is comprehensive enough to assign a code. CMS has published an ICD-10-CM implementation date of October 1, 2013. However, there is an earlier mandate for electronic health-care transaction software to be updated to Version 5010, which will accommodate the alphanumeric reporting in ICD-10-CM, beginning on January 1, 2012. In fact, CMS began accepting transactions submitted with either the older Version 4010 or Version 5010 software on January 1, 2011. Failure to update electronic systems by January 1, 2012, may significantly delay reimbursement claims and require customer service inquiries for resolution, since Version 4010 submissions will no longer be accepted after that date.

Development of Procedure and Supply Coding

To standardize the description of physician services as well as develop a method for compiling actuarial data, the AMA developed a list of descriptive terms and associated numerical codes for reporting medical services, which was published in 1966 as Current Procedural Terminology. This first edition predominantly described surgical procedures, with only limited reference to medical or radiologic procedures. The second edition, published 4 years later, included an expanded description of medical services, as well as a five-digit coding system.

Two additional revisions to CPT were compiled later that decade. The fourth edition was completed in 1977 and contained substantial revisions to include improvements in medical technology. Although one of the intended applications of CPT was to facilitate communication between physicians and insurance agencies, CMS did not adopt CPT as part of their Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS Level I) until 1983. Subsequently, CMS has mandated the use of this system to report services for payment under Part B of the Medicare program. Three years later, CMS also required Medicaid agencies to use the method. Given the growing interest in greater specificity of both diagnostic and procedural coding, the AMA has been working extensively on developing a significant revision to the current edition,4 whose framework has been in place for 25 years. Efforts have included improving granularity by eliminating codes that include “and/or” and “with/without” language so that physicians can more precisely code the work that was done. The fifth edition is currently in use and is updated annually.

Although codes contained in CPT describe the procedures and services provided by physicians to patients, another national coding system was developed to describe nonphysician services, as well as supplies.5 For example, ambulance transportation and dental services, as well as various durable medical equipment and prosthetic devices, are described by this system. These represent Level II HCPCS codes and are published and maintained by CMS. In contrast to the five-digit numeric codes of CPT, these are alphanumeric codes containing an initial letter (between A and V but excluding S) followed by four numbers. Moreover, modifiers can also append these codes, but are comprised of either two letters (-AA to -VP) or alphanumeric symbols.

This documented encounter is then coded based on the type and amount of physician work performed. This may reflect work related to seeing patients in the outpatient setting or work performed in the operating room. These service codes are then linked to the specific diagnostic codes that prompted the service. A billing sheet is then constructed with the diagnostic and procedural codes along with the physician charges and is mailed or sent electronically to the insurance carrier. In the case of Medicare or Medicaid patients, this claim is submitted on an HCFA 1500 form. (The Health Care Financing Administration [HCFA] was the immediate predecessor to CMS.)

Development of the Resource-Based Relative Value System

By the mid-1980s, total health care expenditures had reached $540 billion, representing an 11% share of the gross national product. In fact, proportional spending had more than doubled from the 5.6% share paid in 1965.6 Moreover, reimbursement for physician services by Medicare grew at a 15% compound rate between 1975 and 1987, nearly twice the 7.9% growth rate of the gross national product.7 Finally, observations of utilization of physician services suggested that excessive and unnecessary procedures further contributed to escalating costs.8,9

Several factors, including dissatisfaction with the original payment scheme, growing Part B Medicare expenditures, and a reasonable proposal for a new method, influenced the decision to develop an alternative method of physician payment. The original method for determining the physician payment schedule was based on CPR charges. This resembled the usual, customary, and reasonable (UCR) charge system utilized by private insurers to pay for physicians’ services based on their actual fees. However, the wide variation in the amount Medicare paid for physician services both among physician specialties and among geographic regions caused dissatisfaction within the medical profession.10 Additional dissatisfaction grew among physicians because of the increasing disparity between the lower valuation of patient evaluation services and procedural services.

Consideration was given toward developing a DRG system similar to that developed for hospital payments under Medicare Part A.11 Another option was to create a managed care or capitation model of payment. Finally, a proposal was offered for replacing the CPR method with a payment schedule based on a relative value scale (RVS). Only the CPR and the payment schedule represented fee-for-service methods. Many physicians voiced concern that a DRG or capitated system would threaten clinical judgment in patient care decisions. Moreover, the AMA opposed policies that precluded physicians from charging patients the difference between their fee and the Medicare payment (i.e., balance billing). Because the courts supported Congressional legislation to limit physicians’ fees, development of an RVS seemed to provide the best alternative to the CPR method.

On July 1, 1986, the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act mandated that the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services develop an RBRVS to be submitted to Congress. In addition, the law created the Physician Payment Review Commission (PPRC) to study a variety of additional options for Medicare payment reform, including changing CPR, capitation, and physician DRG.12 The PPRC recommended development of a payment schedule linked to an RBRVS.13

Concurrently, the Harvard study commenced in December 1985 with funding from CMS. The principal investigators, William Hsiao, PhD, and Peter Braun, MD, had previously encountered limited success in a 1979 pilot study that attempted to rank 27 physician services from 5 specialties.14 Five years later, a follow-up study demonstrated more consistent results after estimates of work alone without the addition of complexity were considered. The first phase of the national study supported by CMS developed an RBRVS for 12 physician specialties. In addition, independent funding was obtained for study of 6 additional specialties. Not only were specialty-specific scales developed, but a method for creating cross-specialty links also allowed integration of a single cross-specialty RBRVS. The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1986 provided a 2-year extension for submission of RBRVS to Congress and mandated inclusion of 15 additional specialties during the second phase of the study.15–18

where MFS = Medicare Fee Schedule; RVU = relative value unit; GPCI = geographic practice cost index; w = work; pe = practice expense; pli = professional liability insurance; and CF = conversion factor.

To coordinate changes in CPT with assignment of RVU by CMS, the AMA/Specialty Relative Value Update Committee (RUC) was created in 1991.19 Of the 28 members, 23 are appointed by major national medical specialty societies. The other five panelists include the RUC chair, the co-chair of HCPAC, and members of the AMA, American Osteopathic Association, and CPT Editorial Panel. An RUC Advisory Committee composed of members appointed by 94 specialty societies develop and recommend physician relative work values (wRVU) for new codes to the RUC. Specialty society representatives are responsible for compiling physician survey data to determine the time spent in performing the medical service and ranking the service relative to existing services. In general, procedures are valued by determining, from survey information (RUC survey), the sum of the component time, the intensity, and the risk of performing the procedure. wRVU is added to the practice expense and to the professional liability expense to form the total relative value for the specific procedure. Primarily, only the wRVU is presented to CMS for approval. For the most part, CMS has been supportive of the RUC valuations for procedures, but CMS has authority to disapprove RUC recommendations. Nonetheless, CMS has a historic acceptance rate of more than 90% of the recommendations made by the RUC.

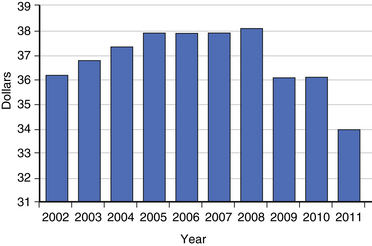

However, the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 requires a budget neutrality adjustment. Because the development of new CPT codes requires subsequent valuation, the new RVU assigned must come from previously valued codes to maintain budget neutrality. Typically, values are maintained within a family of codes, such as the musculoskeletal or neurosurgical sections of the CPT manual. Consequently, there is some disincentive to making significant changes in codes. Some allowance for new technology exists to account for innovations in medical care, thereby creating an opportunity for growth within a family of codes. The methods of maintaining budget neutrality have included reductions in practice expense as well as changes in the conversion factor. Beginning in 1996, CMS decided that annual budget neutrality adjustments would be made to the physician fee schedule conversion factor (Fig. 207-1).

Although work valuations were resource-based, practice expense was based on the AMA’s Socioeconomic Monitoring System (SMS) 1989 Core Survey of a representative sample of 4000 physicians in 34 specialties. However, practice costs, including office rent, wages of nonphysician personnel, equipment, and supplies, were measured overall rather than specific to a given service. Moreover, practice expenses varied among specialties, representing 52.2% of family physicians’ practice costs but only 38.9% of neurosurgeons’ costs. The method enacted by OBRA 89 involved multiplying the specialty-specific practice expense factor by the average Medicare payment of the service in 1991. Similarly, professional liability was calculated based on the proportion of cost multiplied by the Medicare payment. The average neurosurgical professional liability component of practice cost was 7.6%, compared with a 3.9% proportion for the family physician. If the service was provided by more than one specialty, a weighted average of surveyed costs was utilized.

Additional Impact of Legislative Changes on Coding and Reimbursement

The overall purpose of the BBA of 1997 was to erase the federal budget deficit, but as a part of the Act, federal regulators were enabled to more aggressively attack health care fraud and abuse, especially as it relates to the Anti-Kickback Statute. Before implementation of the BBA, the OIG had to pursue anti-kickback cases through the Department of Justice, because these cases were considered criminal matters. The BBA allowed the OIG to pursue anti-kickback violations for civil monetary penalties, thereby lowering the standard of proof and obviating the need to go through the Department of Justice. In addition, the BBA requires CMS to account for health care expenditures and to reimburse health care providers based on documented physician work. CMS is now “required” to reimburse physicians for in-office practice expenses based on actual, rather than “assumed,” office expenses. In a brief time, these legislative acts served to change the face of the practice of medicine in the United States and pushed to the forefront the demand for precise coding and documentation by physicians and other health care providers.

Some methods for preventing fraudulent billing of services have been automated by CMS. Despite the growing number of codes to describe medical services, the work included in many codes overlapped. The process of unbundling, which involves description of a larger procedure with several codes that contain overlapping work, resulted in significant increases in health care expenditures. On January 1, 1996, Medicare initiated the Correct Coding Initiative (CCI) to reduce unbundling and inappropriate reporting of CPT codes.20 CMS contracted with Administar Federal, an Indiana Medicare carrier, to create and maintain a computer program to be used nationally. Despite the $700,000 development cost, Medicare reported savings in excess of $700 million since the program’s inception. Version 5.1 of the CCI, released on April 1, 1999, contained an estimated 120,000 coding edits.14 Most of the edits represented payment policies in which a comprehensive code would be paid while the component code would be disallowed, whereas a small percentage of edits identified mutually exclusive codes, which would not be performed concurrently. Continued quarterly updates of the CCI have been more recently created and maintained by Correct Coding Solutions.

Nomenclature

Coding requires translation of diagnostic and procedural terms to a system that can be classified and manipulated more easily than standard language. Therefore, coding can be no more accurate than the terms being translated. An international committee of anatomists, the Federative Committee on Anatomic Terminology, has undertaken the arduous task of updating an exhaustive list of anatomic terms.21 Although this provides standards for acceptable terms and their spelling, it does not provide definitions or include pathology.

In the field of spine care, it has been well documented that some of the most basic diagnostic terms (e.g., herniated disc and degenerated disc) are not precisely defined and are commonly misunderstood in communications among physicians, patients, insurers, and those who may influence public policy on matters important to spine care. A task force of the North American Spine Society (NASS) recommended preferred terminology for disc pathology and definitions of terms related to disc disorders.22 These efforts were expanded by a joint task force of the NASS, the American Society of Neuroradiologists, and the American Society of Spinal Radiologists.23 Their work does not include attention to disorders of the vertebral canals (i.e., stenosis), disorders of the dorsal elements, or procedures.

Research Applications

Information based on the hospital or outpatient patient experience may be abstracted from patients’ medical records to form administrative databases, which have been used in attempts to describe many aspects of the delivery and utilization of health care.24 A variety of conclusions have been drawn from the research performed using administrative databases. These conclusions can have significant and important implications for patients, providers, and society at large, to the extent that such data inform participants in current health care policy debates.25

Although ICD-9-CM data can be used to create outpatient databases, the most common use of ICD-9-CM is for the coding of inpatient hospital admissions. The processing of the inpatient medical record information into ICD-9-CM-coded language follows a typical sequence. First, hospital medical records personnel abstract clinical information in the hospital medical record and discharge summary. The data identified include diagnostic, procedural, and complication data. This information is then converted into ICD-9-CM code form. Also abstracted are patient demographic data, such as age, gender, length of stay, and discharge status. With this patient demographic data and ICD-9-CM codes, a discharge abstract is constructed. Pooling of discharge abstracts has been referred to as the formation of administrative databases. Administrative databases contain regional discharge abstracts. At the state level, discharge abstracts are received from every hospital within the state. At the federal level, CMS receives nationwide discharge abstracts relating to Medicare patients.26 These data are then available for analysis and research questions.

Several studies have been performed to evaluate the accuracy of the information contained within these databases, as their usefulness relates directly to the quality of the data contained within them.27,28 The limitations of these databases are many, including nonstandardized nomenclature for labeling diagnoses and procedures, inherent deficiencies of the ICD-9-CM system, limitations of the coders assigning the codes, institutional differences in coding practices, incomplete data, and inaccurate data.

Burney I.L., Schreiber G.J., Blaxall M.O., Gabel J.R. Geographic variation in physician’s fees. JAMA. 1978;240:1368-1371.

Faciszewski T., Broste S., Fardon D. Quality of data regarding the diagnosis of spinal disorders in administrative databases: a multicenter study. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1997;79:1481-1488.

Hsiao W.C., Braun P., Dunn D., Becker E.R. Resource-based relative values: an overview. JAMA. 1988;260:2347-2353.

Kassirer J.P. The quality of care and the quality of measuring it. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1263-1264.

Physician Payment Review Commission. Medicare physician payment: an agenda for reform. In In Annual Report to Congress No. 68-227. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1987.

Physician Payment Review Commission. Medicare physician payment. In In Annual Report to Congress. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1988.

1. World Health Organization. International classification of diseases. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1977. pp 7–33

2. Hart A.C., Hopkins C.A., editors. Medicode ICD-9-CM professional for physicians, International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision, clinical modification, ed 6, Reston, VA: St Anthony’s, 2001.

3. Medicode ICD-10 Made Easy. Reston, VA: St Anthony’s; 2000.

4. Current Procedural Terminology: CPT 2002. Chicago: American Medical Association; 2001.

5. Jones-Burns M.K. St. Anthony’s HCPCS Level II Code Book. Reston, VA: St. Anthony’s; 1997. pp 1–3

6. Jacobs P. Behavior of supply. In: Jacobs P., editor. The economics of health and medical care. ed 3. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen; 1991:168-174.

7. Roper W.L. Statement before Subcommittee on Health of the Committee on Ways and Means, U.S. House of Representatives. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Care Financing Administration; 1988.

8. Chassin M.R., Kosecoff J., Park R.E., et al. Does inappropriate use explain geographic variations in the use of health care services? A study of three procedures. JAMA. 1987;258:2533-2537.

9. Greenspan A.M., Kay H.R., Berger B.C., et al. Incidence of unwarranted implantation of permanent cardiac pacemakers in a large medical population. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:158-163.

10. Burney I.L., Schreiber G.J., Blaxall M.O., Gabel J.R. Geographic variation in physician’s fees. JAMA. 1978;240:1368-1371.

11. Mitchell J.B., Physician DRGs. N Engl J Med. 1985;13:670-675.

12. Physician Payment Review Commission. Medicare physician payment: an agenda for reform. In In Annual Report to Congress No. 68-227. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1987.

13. Physician Payment Review Commission. Medicare physician payment. In In Annual Report to Congress. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1988.

14. Hsiao W.C., Stason W.B. Toward developing a relative value scale for medical and surgical services. Health Care Financ Rev. 1979;1:23-29.

15. Hsiao W.C., Braun P., Becker E.R., Thomas S.R. The resource-based relative value scale. JAMA. 1987;258:799-802.

16. Hsiao W.C., Braun P., Dunn D., Becker E.R. Resource-based relative values: an overview. JAMA. 1988;260:2347-2353.

17. Hsiao W.C., Braun P., Dunn D., Becker E.R. Results and policy implications of the resource-based relative value study. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:881-888.

18. Hsiao W.C., Braun P., Yntema D., Becker E.R. Estimating physicians’ work for a resource-based relative value scale. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:835-841.

19. Gallagher P.E., editor. Medicare RBRVS: the Physician’s Guide 2002. Chicago: American Medical Association. 2002:2-48.

20. Kirschner C.G., Reyes D. An update on Medicare’s correct coding initiative. In CPT Assistant. Chicago: American Medical Association; 1999. 7–9

21. Federative Committee on Anatomical Terminology. Terminologia anatomica. New York: Georg Thieme Verlag; 1998.

22. Fardon D.F., Herzog R.J., Mink J.H., et al. Nomenclature of lumbar disc disorders. In: Garfin S.R., Vaccaro A.R., editors. Orthopaedic knowledge update—spine. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 1997:A3-A14.

23. Fardon DF, Milette PM, et al: Personal communication (publication data pending).

24. Faciszewski T. Spine update: administrative databases in spine research. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1997;22:1269-1275.

25. Kassirer J.P. The quality of care and the quality of measuring it. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1263-1264.

26. Fisher E.S., Whaley F.S., Krushat W.M., et al. The accuracy of Medicare’s hospital claims data (progress has been made, but problems remain). Am J Public Health. 1992;82:243-248.

27. Faciszewski T., Broste S., Fardon D. Quality of data regarding the diagnosis of spinal disorders in administrative databases: a multicenter study. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1997;79:1481-1488.

28. Faciszewski T., Johnson L., Noren C., Smith M. Administrative database complication coding in anterior spinal fusion procedures: what does it mean? Spine. 1995;20:1783-1788.