Quality and Evidence-Based Respiratory Care

After reading this chapter you will be able to:

Describe the elements that constitute quality respiratory care.

Describe the elements that constitute quality respiratory care.

Explain methods used for monitoring the quality of respiratory care that is provided.

Explain methods used for monitoring the quality of respiratory care that is provided.

Explain how respiratory care protocols enhance the quality of respiratory care services.

Explain how respiratory care protocols enhance the quality of respiratory care services.

Elements of A Hospital-Based Respiratory Care Program: Roles Supporting Quality Care

Medical Direction

The medical director of respiratory care is professionally responsible for the clinical function of the department and provides oversight of the clinical care that is delivered (Box 2-1). Medical direction for respiratory care is usually provided by a pulmonary/critical care physician or an anesthesiologist. Whether the role of a respiratory care service medical director is designated as a full-time or part-time position, it is a full-time responsibility; the medical director must be available on a 24-hour basis for consultation with and to give advice to other physicians and the respiratory care staff. The current philosophy of cost containment and cost-effectiveness, dictated by medical care market forces, poses a challenge to the medical and technical leadership of respiratory care services to provide increasingly high-quality patient care at low cost. A medical director must possess administrative and medical skills.1

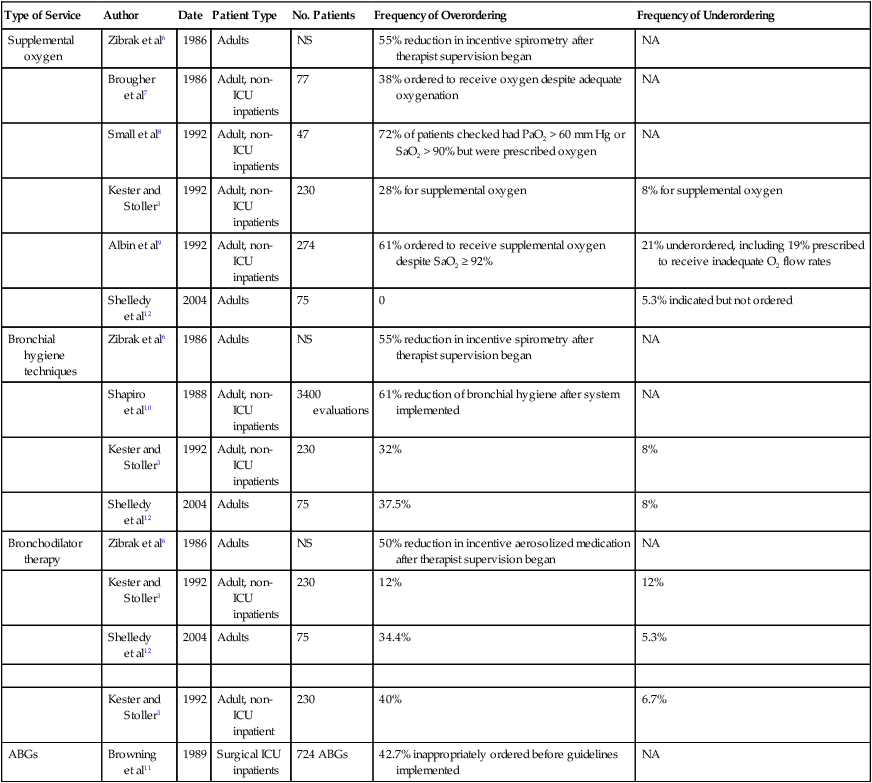

Perhaps the most essential aspect of providing quality respiratory care is to ensure that the care being provided is indicated and that it is delivered competently and appropriately. Traditionally, the physician has evaluated patients for respiratory care and has written the specific respiratory therapy orders for the respiratory therapist (RT) to follow. However, such traditional practices have often been shown to be associated with misallocation of respiratory care.2–4 This misallocation may consist of ordering therapy that is not indicated, ordering therapy to be delivered by an inappropriate method, or failing to provide therapy that is indicated.5 Table 2-1 reviews studies evaluating the allocation of respiratory care services and the frequency of misallocated care.3,6–12 These studies provide ample evidence that misallocation of respiratory care occurs frequently. Such misallocation has led to the use of respiratory care protocols that are implemented by RTs (as described under Methods for Enhancing the Quality of Respiratory Care).

TABLE 2-1

Frequency of Misallocation of Respiratory Care Services in Selected Series

| Type of Service | Author | Date | Patient Type | No. Patients | Frequency of Overordering | Frequency of Underordering |

| Supplemental oxygen | Zibrak et al6 | 1986 | Adults | NS | 55% reduction in incentive spirometry after therapist supervision began | NA |

| Brougher et al7 | 1986 | Adult, non-ICU inpatients | 77 | 38% ordered to receive oxygen despite adequate oxygenation | NA | |

| Small et al8 | 1992 | Adult, non-ICU inpatients | 47 | 72% of patients checked had PaO2 > 60 mm Hg or SaO2 > 90% but were prescribed oxygen | NA | |

| Kester and Stoller3 | 1992 | Adult, non-ICU inpatients | 230 | 28% for supplemental oxygen | 8% for supplemental oxygen | |

| Albin et al9 | 1992 | Adult, non-ICU inpatients | 274 | 61% ordered to receive supplemental oxygen despite SaO2 ≥ 92% | 21% underordered, including 19% prescribed to receive inadequate O2 flow rates | |

| Shelledy et al12 | 2004 | Adults | 75 | 0 | 5.3% indicated but not ordered | |

| Bronchial hygiene techniques | Zibrak et al6 | 1986 | Adults | NS | 55% reduction in incentive spirometry after therapist supervision began | NA |

| Shapiro et al10 | 1988 | Adult, non-ICU inpatients | 3400 evaluations | 61% reduction of bronchial hygiene after system implemented | NA | |

| Kester and Stoller3 | 1992 | Adult, non-ICU inpatients | 230 | 32% | 8% | |

| Shelledy et al12 | 2004 | Adults | 75 | 37.5% | 8% | |

| Bronchodilator therapy | Zibrak et al6 | 1986 | Adults | NS | 50% reduction in incentive aerosolized medication after therapist supervision began | NA |

| Kester and Stoller3 | 1992 | Adult, non-ICU inpatients | 230 | 12% | 12% | |

| Shelledy et al12 | 2004 | Adults | 75 | 34.4% | 5.3% | |

| Kester and Stoller3 | 1992 | Adult, non-ICU inpatient | 230 | 40% | 6.7% | |

| ABGs | Browning et al11 | 1989 | Surgical ICU inpatients | 724 ABGs | 42.7% inappropriately ordered before guidelines implemented | NA |

NS, Not stated; NA, not assessed.

Modified from Stoller JK: The rationale for therapist-driven protocols. Respir Care Clin N Am 2:1–14, 1996.

Respiratory Therapists

In addition to capable medical direction and the application of well-constructed respiratory care protocols (see p. 26), capable RTs are an indispensable element of a quality respiratory care program. The quality of RTs depends primarily on their training, education, experience, and professionalism. Training teaches students to perform tasks at a competent level, whereas clinical education provides students with a knowledge base they can use in evaluating a situation and making appropriate decisions.13 Both adequate training and clinical education are required to produce qualified RTs for assessment of patients and implementation of respiratory care protocols.14

Designations and Credentials of Respiratory Therapists

There are two levels of general practice credentialing in respiratory care: (1) certified respiratory therapists (CRTs) and (2) registered respiratory therapists (RRTs). Students eligible to become CRTs and RRTs are trained and educated in colleges and universities. After completion of an approved respiratory care educational program, a graduate may become credentialed by taking the entry-level examination to become a CRT. A CRT may be eligible to sit for the registry examinations to become a credentialed RRT. Students who complete a 2-year program graduate with an associate degree, and students who complete a 4-year program receive a baccalaureate degree. Some RTs go on to complete a graduate degree (e.g., master or doctorate) with additional study in the areas of respiratory care, education, management, or health sciences. The further development of graduate education in respiratory care has been encouraged by the American Association for Respiratory Care (AARC), and programs are both currently available and under development.15

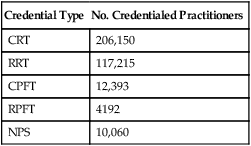

The primary method of ensuring quality in respiratory care is voluntary certification or registration conducted by the National Board for Respiratory Care (NBRC). The NBRC is an independent national credentialing agency for individuals who work in respiratory care and related services. The NBRC is cooperatively sponsored by the AARC, the ACCP, the ASA, the ATS, and the National Society for Pulmonary Technology. Representatives of these organizations make up the governing board of the NBRC, which assumes the responsibility for all examination standards and policies through a standing committee. The NBRC provides the credentialing process for both the entry-level CRT and the advanced-practitioner RRT. As established in January 2006, to be eligible for either the CRT or the RRT examination, all candidates must have an associate degree or higher. An additional advanced-practitioner credential, the neonatal/pediatric specialist (NPS), has been established for the field of pediatrics. The NBRC also encourages professionals in the field to maintain and upgrade their skills through voluntary recredentialing. Both CRTs and RRTs may demonstrate ongoing professional competence by retaking examinations. Individuals who pass these examinations are issued a certificate recognizing them as “recredentialed” practitioners. In addition to the certification and registration of RTs, the NBRC provides credentialing in the area of pulmonary function testing for certified pulmonary function technologists (CPFTs) and registered pulmonary function technologists (RPFTs). Since its inception, the NBRC has issued more than 350,000 professional credentials to more than 209,000 individuals. As of 2010, there were approximately 206,150 active RTs, many of whom hold more than one credential. Table 2-2 shows the distribution of these credentialed individuals.

TABLE 2-2

Distribution of Credentialed Practitioners

| Credential Type | No. Credentialed Practitioners |

| CRT | 206,150 |

| RRT | 117,215 |

| CPFT | 12,393 |

| RPFT | 4192 |

| NPS | 10,060 |

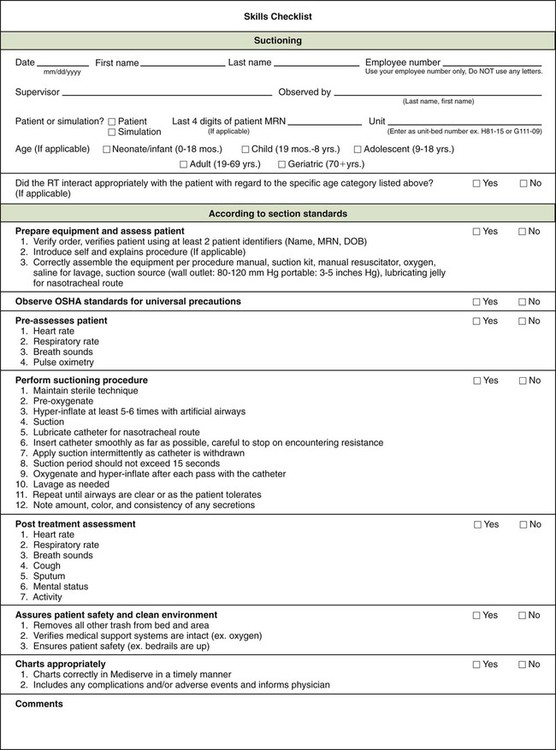

Licensure and certification help ensure that only qualified RTs participate in the practice of respiratory care. Many institutions conduct annual skills checks or competency evaluations in compliance with TJC requirements. Beyond TJC–required skills checks, experience with respiratory care protocols suggests the need to develop and monitor additional skills among RTs (Box 2-2). Assurance and maintenance of these skills require ongoing training and quality review programs, which are discussed in the section on Monitoring Quality Respiratory Care.

Professionalism

By definition, professionalism is a key attribute to which all RTs should aspire and that must guide respiratory care practice. Webster’s New Collegiate Dictionary defines a profession as “a calling that requires specialized knowledge and often long and intensive academic preparation.” A professional is characterized as an individual conforming to the technical and ethical standards of a profession. RTs demonstrate their professionalism by maintaining the highest practice standards, by engaging in ongoing learning, by conducting research to advance the quality of respiratory care, and by participating in organized activities through professional societies such as the AARC and associated state societies. Box 2-3 lists the professional attributes of the RT. We emphasize the importance of these attributes because the continued value and progress of the field depend critically on the professionalism of each practitioner.16

In the highly regulated careers of health care, professionalism also requires compliance with external standards, such as the standards set by TJC and by the government. One such standard is defined by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996. HIPAA sets standards regarding the way sensitive health care information is communicated and revealed in the transmission of medical records and in the written and verbal communication of information in the hospital. Some specific provisions of HIPAA are presented in Box 2-4. As with all hospital and health care personnel, standards of respiratory therapy professionalism require knowledge of HIPAA and compliance with its terms.

Methods for Enhancing Quality Respiratory Care

Respiratory Care Protocols

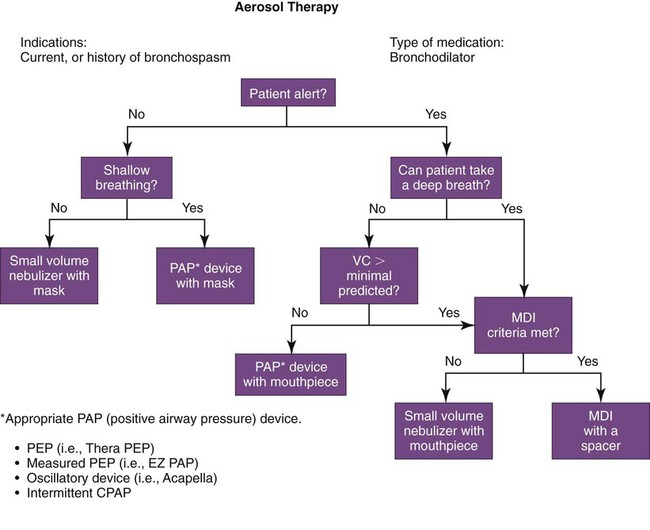

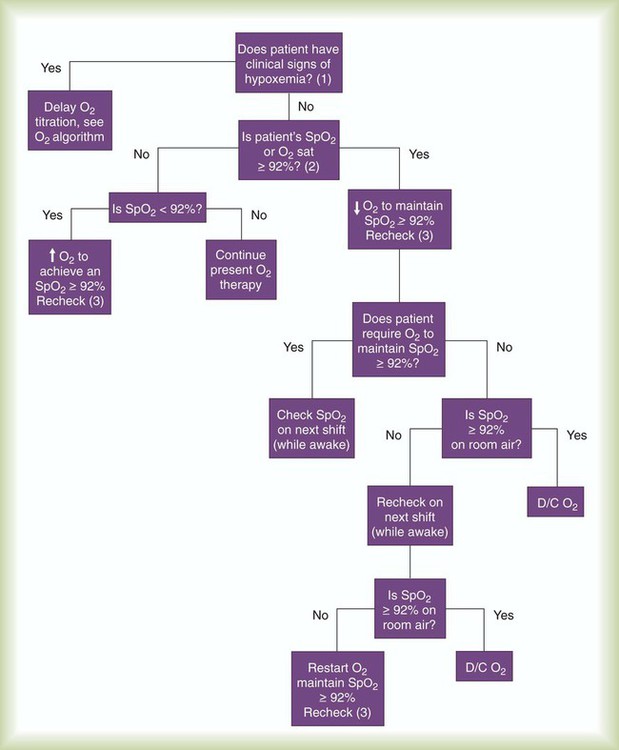

In an effort to improve the allocation of respiratory care services, respiratory care protocols (also known as therapist-driven protocols) have been developed and are in use in many hospitals in the United States, Canada, and other countries. Respiratory care protocols are guidelines for delivering appropriate respiratory care treatments and services (i.e., treatments and services that are indicated, delivered by the correct method, and discontinued when no longer needed). Protocols may be written in outline form or may use algorithms (an example of which is a branching logic flow diagram [Figures 2-1 and 2-2]).

Gaylin and colleagues17 conducted a telephone survey in 1999 of 371 RT members of the AARC, of whom 51% were practitioners, 26% were clinical supervisors, and 23% were administrators. When asked if their organizations used guidelines or protocols, 98% of the respondents indicated that they did. Of the 2% who did not, 53% were planning their use.17 A survey conducted by the AARC in 2005 indicated that of 681 responding hospitals, 73% were providing care by means of at least one protocol.18 More recently, the 2009 AARC Human Resources Survey showed that of 2764 responders, about two-thirds (65.7%) indicated that they have delivered respiratory care by protocol.19 The use of respiratory care protocols by qualified RTs is a logical practice based on the premise that well-trained RTs possess extensive knowledge of respiratory care modalities and have the assessment and communication skills required to execute the protocols effectively.20

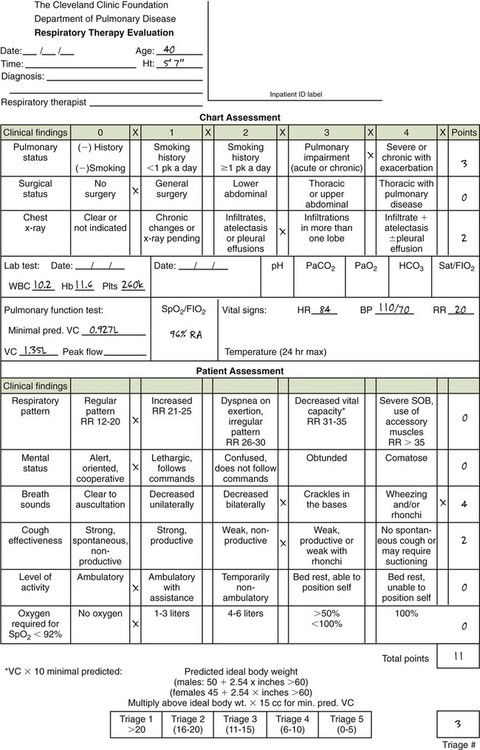

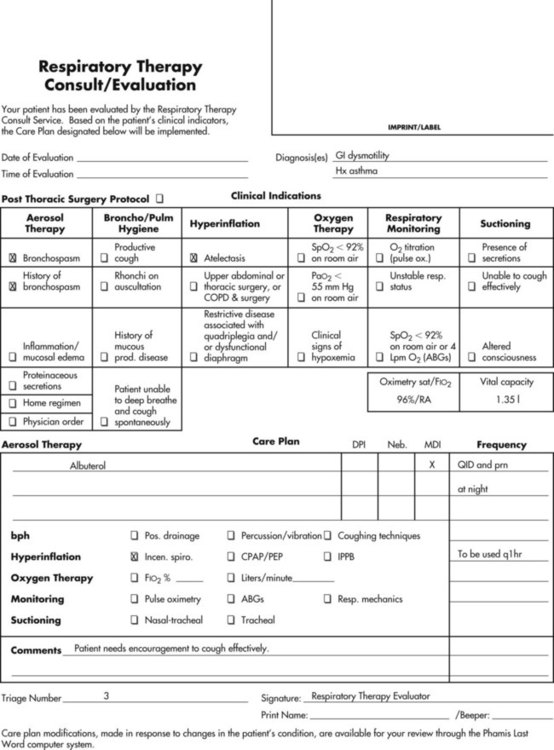

The success of a respiratory care protocol program requires several key elements, including active and committed medical direction, capable RTs, collaboration with physicians and nurses, careful monitoring, and a responsive hospital environment (Box 2-5). As further evidence of the widespread acceptance of protocols, the ACCP has identified the elements of an acceptable respiratory care protocol (Box 2-6). This document may serve as a guide for developing protocols. Protocols may be constructed for individual therapies, such as aerosol therapy, bronchopulmonary hygiene, oxygen therapy, hyperinflation techniques, suctioning, and pulse oximetry. Protocols also can be written for a specific purpose, such as arterial blood gas (ABG) sampling, weaning from mechanical ventilation, decannulating a tracheostomy, and titrating oxygen therapy.

Features of RT departments that are ready for and that embrace change have been studied21 and are presented in Box 2-7. Steps and tactics to ensure successful implementation of respiratory care protocols are described in Box 2-8. Selecting a planning team with broad membership that includes physicians, nurses, and administrators is a key element in developing a protocol implementation process that avoids potential barriers and satisfies the institution’s specific and unique requirements. Once protocols have been designed, it is often advisable to pilot them either individually or on a single hospital floor or unit. This staged rollout with an initial pilot trial allows an opportunity to work out unanticipated problems and obtain helpful feedback from the individuals involved before using the protocols on a hospital-wide basis.

A comprehensive approach for using protocols is to combine specific protocols to form a respiratory therapy consult service or an evaluate-and-treat program, which is used in institutions such as the University of California at San Diego and the Cleveland Clinic. With the use of a respiratory therapy consult service, the sequence of events for a respiratory therapy consult may occur as shown in Box 2-9.

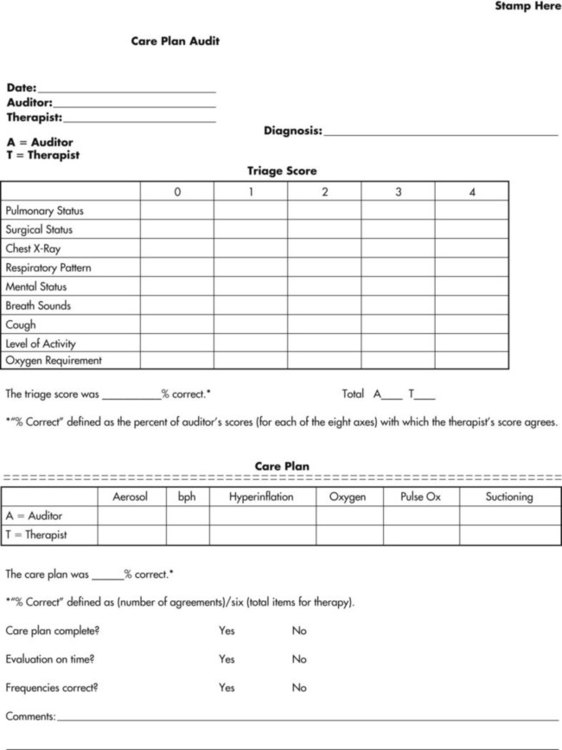

A carefully structured assessment tool and care plan form (Figures 2-3 and 2-4) are essential elements for a comprehensive protocol program. These tools help ensure consistency among therapist evaluators. The following Mini Clini on Writing a Respiratory Care Plan shows how an assessment tool and care plan document, used in conjunction with corresponding algorithms, can guide therapists in formulating an appropriate respiratory care plan.

Demonstrated advantages of respiratory care protocols include better allocation of respiratory care services without an increased frequency of respiratory care treatments and cost savings. Other advantages include more dynamic respiratory care with more adjustment of respiratory care services to keep pace with patients’ changing clinical status and more versatile use of respiratory care services.12,22–25

Monitoring Quality Respiratory Care

Intrainstitutional quality assurance often uses skills checks or competencies. Competence, or the quality of being competent, can be defined as having suitable or sufficient skill, knowledge, and experience for the purposes of a specific task.26 Competence for a specific skill is frequently determined by observation of the practitioner’s performance of the skill according to a prescribed checklist. Annual competency checks are documented for skills and procedures that carry some degree of patient risk (e.g., arterial puncture, aerosol therapy, bilevel positive airway pressure setup). An example of a skills checklist is shown in Figure 2-5.

Although skills checks have traditionally been done in person or with direct supervision of patient care activities, a new dimension of skills training and certification that is being widely implemented is the use of clinical simulation, using either low-fidelity or high-fidelity simulation trainers. Such simulation training (see Chapter 7), in which RTs use technology that attempts to reproduce reliably a true patient or true patient scenario, is similar to the flight simulator training that commercial airline pilots undergo to achieve certification to fly various airplanes. Uses of simulation training in respiratory therapy involve intubation, ventilator management, arterial line placement, and optimizing teamwork in acute resuscitation scenarios.27

TJC requires a hospital service to have a quality assurance plan to provide a system for controlling quality. Nine generally recognized steps for a quality assurance plan are used as the basis for quality assurance programs (Box 2-10).

Current standards of TJC for accreditation emphasize organization-wide efforts for performance improvement. Despite increased emphasis on cost containment, quality care remains the first goal of hospitals and respiratory care services. Performance improvement, also commonly called continuous quality improvement, is an ongoing process designed to detect and correct factors hindering the provision of quality and cost-effective health care. This process crosses department boundaries and follows the continuum of the patient’s care. In 2009, TJC set forth three standards for monitoring performance improvement along with associated elements of performance detailing how the monitoring is to be conducted. These standards are listed in Box 2-11. Meeting quality goals is increasingly being tied to reimbursement rates by the CMS and insurers to hospitals; this phenomenon has been called “pay for performance.”28 Beyond general monitoring goals for respiratory care, use of respiratory care protocols creates the need for additional quality monitoring benchmarks regarding correctness, consistency, efficacy, and effectiveness (Box 2-12).

Monitoring correctness of respiratory care plans can be accomplished by using a care plan audit system. Care plan auditors must be therapists who are experienced in providing respiratory care and patient assessment. The auditors must also be practiced in using the institution’s protocol system and in writing care plans. With an auditing system, the auditor writes a care plan for a patient and compares it with the care plan written by the therapist evaluator to determine correctness. A specified number of audits should be performed monthly, with results tabulated and reported monthly or quarterly, depending on the size of the hospital. Feedback must be provided to the evaluators whose care plans are being audited to show their proficiency or to indicate areas that require improvement. Figure 2-6 shows a form used at the Cleveland Clinic to provide feedback to evaluators.

Peer Review Organizations

In recent years, health care organizations have attempted to improve the quality of patient care while reducing costs by implementing several innovative health care models. Historically, models that were commonly implemented were hospital restructuring and redesign and patient-focused care. Protocols and disease management represent continuing solutions. Accountable care organizations (ACOs)29 have also been proposed as a solution to enhance quality and lessen cost. An ACO can be broadly thought of as an emerging model in which a group of health care providers aligns and agrees together to try to meet quality and care targets and to receive payments as a collective entity, from which individual payments can then be disbursed. The ACO can benefit as a group from its success and can absorb losses as a group related to its failure to meet the targets.

Restructuring and redesign involved changing the basic organization of health care services in an attempt to do more with less while increasing value. Approaches for restructuring commonly included cross-training employees, using unlicensed assistive staff, and decentralizing services.30 When respiratory care departments are decentralized and respiratory care management is eliminated, RTs are deployed to individual nursing units and report to nursing supervisors. When complete decentralization occurs, the responsibilities of equipment purchase and maintenance, continuing education, and quality improvement may be assigned to nursing personnel, who often are uncomfortable with these additional burdens.30

Protocols

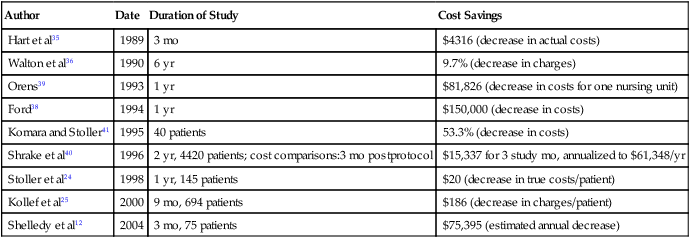

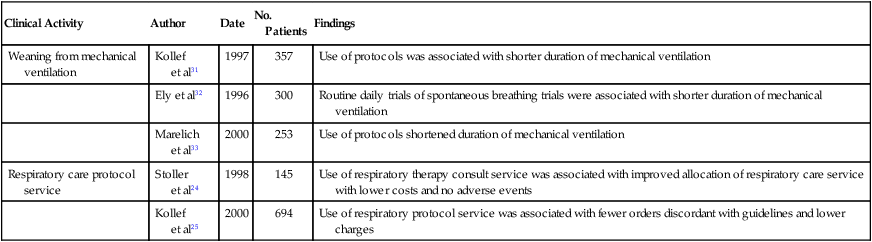

The widespread use and acceptance of respiratory care protocols have been encouraged by studies reporting reduced misallocation of respiratory care and the cost savings associated with protocols. In addition to observational studies,22 the benefits of RT protocols have been shown in randomized, controlled trials for weaning patients from mechanical ventilation31–34 and for allocating respiratory therapy to adult inpatients not in intensive care units (ICUs).24,25 Table 2-3 presents selected studies showing the effect of respiratory care protocols on the misallocation of respiratory therapy. Most studies show a significant decrease in overordering respiratory care services, whereas only a few address underordering services, which is a phenomenon more difficult to assess. Table 2-4 reviews studies addressing the cost savings associated with using protocols, which suggest that respiratory care protocols can effect savings by enhancing appropriate allocation of respiratory care services.12,24,25,35–41 Table 2-5 summarizes the results of five randomized, controlled trials on the effectiveness of respiratory care protocols. These studies establish the efficacy of respiratory care protocols in weaning patients from mechanical ventilation30–32 and in enhancing the allocation of services to adult patients not in ICUs.23,24

TABLE 2-3

Changes in Modalities After Protocol Implementation

| Author and Year Published | Observed Reductions in Misallocated Therapy After Implementation of Protocols | Change from Preprotocol to Current Status |

| Hart et al,35 1989 | 37% (aerosol, hyperinflation) | 48%-11% |

| Walton et al,36 1990 | 49.1% (aerosol, chest physiotherapy) | |

| Beasley et al,37 1992 | 11.9% (blood gas use) | 42.7%-30.8% |

| Ford,38 1994 | 57% (aerosol, chest physiotherapy) | 7000-4000 treatments |

| Orens,39 1993 | 35% (aerosol, bronchopulmonary, hygiene, hyperinflation oxygen, oximetry) |

From Haney DJ: Therapist-driven protocols for adult non-intensive care unit patients: availability and efficacy. Respir Care Clin N Am 2:93–104, 1996.

TABLE 2-4

Cost Savings Associated With Respiratory Care Protocols

| Author | Date | Duration of Study | Cost Savings |

| Hart et al35 | 1989 | 3 mo | $4316 (decrease in actual costs) |

| Walton et al36 | 1990 | 6 yr | 9.7% (decrease in charges) |

| Orens39 | 1993 | 1 yr | $81,826 (decrease in costs for one nursing unit) |

| Ford38 | 1994 | 1 yr | $150,000 (decrease in costs) |

| Komara and Stoller41 | 1995 | 40 patients | 53.3% (decrease in costs) |

| Shrake et al40 | 1996 | 2 yr, 4420 patients; cost comparisons:3 mo postprotocol | $15,337 for 3 study mo, annualized to $61,348/yr |

| Stoller et al24 | 1998 | 1 yr, 145 patients | $20 (decrease in true costs/patient) |

| Kollef et al25 | 2000 | 9 mo, 694 patients | $186 (decrease in charges/patient) |

| Shelledy et al12 | 2004 | 3 mo, 75 patients | $75,395 (estimated annual decrease) |

Modified from Haney DJ: Therapist-driven protocols for adult non-intensive care unit patients: availability and efficacy. Respir Care Clin N Am 2:93–104, 1996.

TABLE 2-5

Summary of Available Randomized Trials on the Effectiveness of Respiratory Care Protocols

| Clinical Activity | Author | Date | No. Patients | Findings |

| Weaning from mechanical ventilation | Kollef et al31 | 1997 | 357 | Use of protocols was associated with shorter duration of mechanical ventilation |

| Ely et al32 | 1996 | 300 | Routine daily trials of spontaneous breathing trials were associated with shorter duration of mechanical ventilation | |

| Marelich et al33 | 2000 | 253 | Use of protocols shortened duration of mechanical ventilation | |

| Respiratory care protocol service | Stoller et al24 | 1998 | 145 | Use of respiratory therapy consult service was associated with improved allocation of respiratory care service with lower costs and no adverse events |

| Kollef et al25 | 2000 | 694 | Use of respiratory protocol service was associated with fewer orders discordant with guidelines and lower charges |

From Stoller JK: Are respiratory therapists effective? Assessing the evidence. Respir Care 46:56, 2001.

Disease Management

Disease management refers to an organized strategy of delivering care to a large group of individuals with chronic disease to improve outcomes and reduce cost. Disease management has been defined as a systematic population-based approach to identify persons at risk, intervene with specific programs of care, and measure clinical and other outcomes.42,43 Disease management programs comprise four essential components: (1) an integrated health care system that can provide coordinated care across the full range of patients’ needs; (2) a comprehensive knowledge base regarding the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of disease that guides the plan of care; (3) sophisticated clinical and administrative information systems that can help assess patterns of clinical practice; and (4) a commitment to continuous quality improvement. Disease management programs may be developed for chronic conditions such as asthma, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and congestive heart failure.

Evidence-Based Medicine

Another important concept regarding quality care is evidence-based medicine. Evidence-based medicine refers to an approach to determining optimal clinical management based on several practices, as follows:43–47 (1) a rigorous and systematic review of available evidence, (2) a critical analysis of available evidence to determine what management conclusions are most sound and applicable, and (3) a disciplined approach to incorporating the literature with personal practice and experience. In a broader context, evidence-based medicine can be thought of as understanding and using the best quality evidence available (i.e., the best-designed, most rigorous clinical trials) to support the most appropriate and correct possible clinical decisions.

In rating the quality of scientific evidence, it is important to recognize the various designs and types of study designs from which scientific evidence comes.48 The simplest and least rigorous design is a single case report, in which a new clinical issue or problem is described in a single patient. A description of the favorable outcome of using a new mode of mechanical ventilation in one patient with refractory hypoxemia would be a single case report. Although single case reports have value in pointing out new insights and new possibilities for treatment, disease associations, or disease causation, they cannot prove the effectiveness of a treatment or the causality of a risk factor because they, by nature, lack a control or comparison group (i.e., a group that is similar to the patient or patients described, differing only in whether the risk factor of interest was present or the treatment of interest was applied). Collecting a group of patients with similar clinical features is called a case series and may have greater impact in that it suggests that the issue is more general than in a single patient alone. However, similar to a single case report, a case series cannot prove the efficacy of a treatment or the causality of a risk factor because no comparison or control group is included.

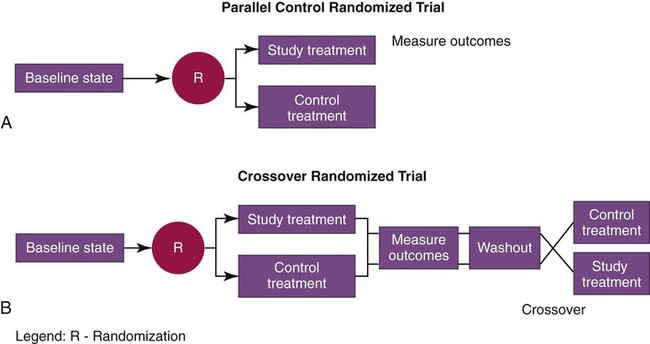

Variants of the randomized controlled trial include the parallel-control study and the crossover study (Figure 2-7). Parallel-control treatment studies compare two groups: one receives the treatment being studied, and the other receives the control treatment. Sometime after the end of the treatment, outcomes of the two groups are assessed and compared regarding the main outcomes of interest in the study. A parallel-control randomized trial of low-stretch ventilation for ARDS would compare one group of patients receiving low-stretch ventilation with another (otherwise similar) group receiving conventional, higher stretch ventilator settings, and the two groups would be compared after a prespecified time period with regard to key outcomes, such as survival, discharge from the ICU, and organ system failures. This design was used in the ARDS Net clinical trial showing the superiority of using a tidal volume of 6 ml/kg (ideal body weight) in managing patients with acute lung injury or ARDS.49

Evidence-based medicine requires knowledge of how to analyze carefully the results of clinical trials (e.g., randomized controlled trials and observational cohort studies) and how to incorporate the results of such research into high-quality clinical practice. Other tools of evidence-based medicine include systematically reviewing the available literature, or what is called meta-analysis of the literature.28 A meta-analysis of a clinical issue (e.g., does a low-stretch mechanical ventilation strategy improve survival in ARDS?49) identifies, analyzes, and summarizes the body of literature about this topic by assessing the quality of the available evidence and giving greater weight to better designed, more rigorous studies. Sometimes, meta-analyses pool the actual data from different trials together when pooling is scientifically and statistically permissible. In other instances (called narrative analyses), the meta-analysis simply evaluates the quality of the data from each available trial (based on explicit methodologic criteria) to offer a conclusion about the clinical issue.

A meta-analysis performed as part of an evidence-based approach to determining the optimal ventilatory approach for ARDS might weigh the results of large randomized clinical trials of low-stretch versus conventional tidal volume approach mechanical ventilation more heavily than the results of small observational studies. A 2003 evidence-based review of the management of individuals with alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency (see Chapter 23) issued graded recommendations for testing for this genetic cause of COPD.50 A level A recommendation (i.e., that testing should be performed) was issued to test all symptomatic adults with airflow obstruction on pulmonary function tests (whether carrying the diagnosis of emphysema, COPD, or asthma in which airflow obstruction fails to reverse completely with bronchodilators), asymptomatic individuals with persistent airflow obstruction on pulmonary function tests with identifiable risk factors (e.g., cigarette smoking, occupational exposure), individuals with unexplained liver disease, and adults with a skin condition called necrotizing panniculitis.50 Although the hope is that issuing such evidence-based guidelines will improve the care that such individuals receive by allowing clinicians to access efficiently the best available information, experience suggests that clinicians may be slow to adopt the best available evidence in caring for their patients.51

Although some authors point out that evidence-based medicine does not differ from prior practice in which clinicians were always called on to analyze carefully available data and make clinical judgments based on the best-quality information available, evidence-based medicine does specify precise methods for analyzing available information and allowing the clinician to judge best the available evidence. As a measure of the importance of evidence-based medicine in respiratory care, several articles in Respiratory Care considered the effectiveness of RTs and of various respiratory care treatment modalities using an evidence-based approach.45–47 The Clinical Practice Guidelines of the American Association for Respiratory Care are being systematically reviewed to reflect the rigorous techniques of evidence-based medicine and to ensure that guidelines for respiratory care management reflect the best available evidence.47 The proof that low-stretch ventilation is associated with improved survival in patients with ARDS and the methods used to enhance awareness of this best practice are further examples of evidence-based medical practice.