18

Purpura and Disorders of Microvascular Occlusion

• As purpuric lesions fade, their color evolves from red-purple or blue to brown or yellow-green.

• Primary purpura has a broad differential diagnosis, and it is helpful to categorize purpuric lesions based on their size and morphology.

– Petechiae: ≤3 mm and macular (Table 18.1; Fig. 18.1A).

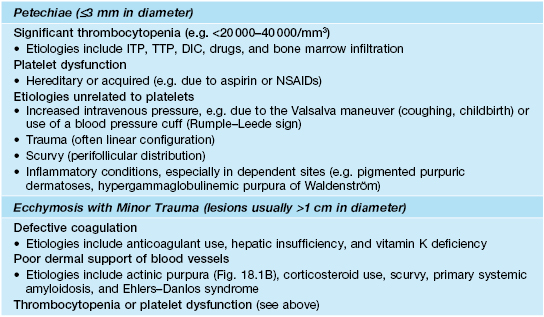

Table 18.1

Causes of petechiae and ecchymosis with minor trauma.

DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation; ITP, idiopathic thrombocytopenia purpura; TTP, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.

Fig. 18.1 Clinical examples of petechiae and purpura. A Round to oval petechiae, ≤3 mm in diameter. B Actinic (solar) purpura and pseudoscars, both in sites of actinic damage plus trauma. C Non-inflammatory (bland) retiform purpura as well as hemorrhagic bullae in a patient with disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). D Palpable purpura due to cutaneous small vessel vasculitis (inflammation plus hemorrhage). A, Courtesy, Warren Piette, MD; B, Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD; C, Courtesy, Judit Stenn, MD.

– Ecchymoses: usually >1 cm and macular with round/oval to slightly irregular borders, and typically have an element of trauma in their pathogenesis (see Table 18.1; Fig. 18.1B); a greater volume of hemorrhage leads to a hematoma, which is palpable.

– Retiform purpura: reticulated, branching or stellate morphology, which reflects occlusion of the vessels that produce the livedo reticularis pattern (see Chapter 87; Tables 18.2 and 18.3; Figs. 18.1C and 18.2–18.9).

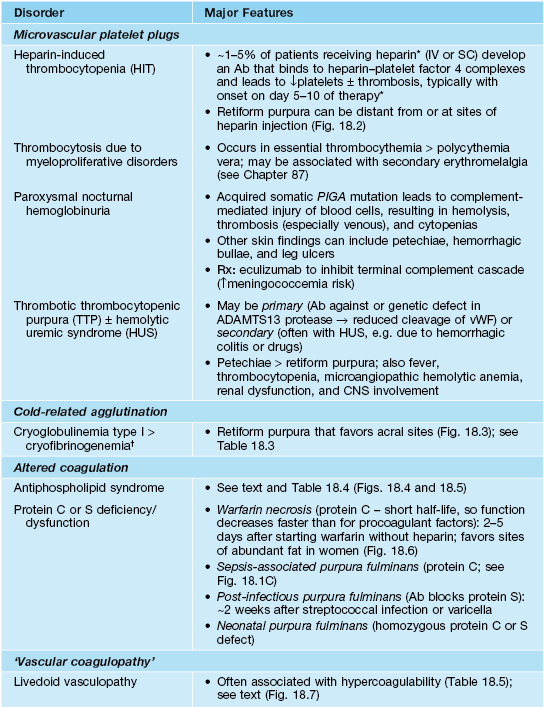

Table 18.2

Causes of retiform purpura.

* Less common with low-molecular-weight heparin (≤1%) than unfractionated heparin; a transient decrease in the platelet count can also occur within the first 2 days of heparin therapy due to its direct effects on platelet activation.

† May be an incidental finding in hospitalized patients; cold agglutinins rarely lead to acrocyanosis or purpura.

** Skin lesions associated with subacute endocarditis are more likely to be inflammatory due to immune complex deposition, e.g. Osler’s nodes (tender red-purple papules), rather than Janeway lesions (purpuric macules; more common in acute endocarditis) on the hands and feet.

‡ Cutaneous microthrombi and superficial thrombophlebitis have also been described.

Ab, antibody; PIGA, phosphatidylinositol glycan anchor class A; vWF, von Willebrand factor.

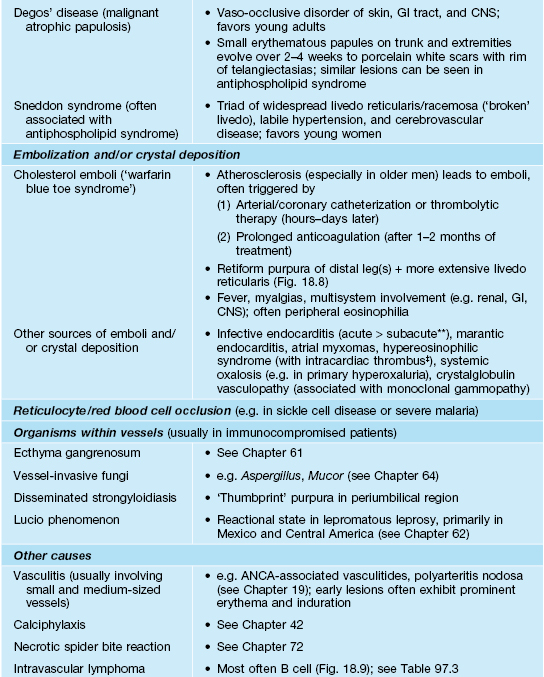

Table 18.3

Classification of cryoglobulins.

* Typically have rheumatoid factor activity (i.e. are directed against the Fc portion of IgG).

** Referred to as ‘mixed’ cryoglobulins.

HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

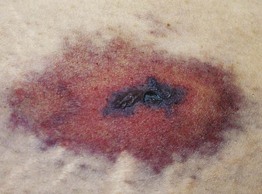

Fig. 18.2 Heparin necrosis at site of subcutaneous heparin injection. Note the branching or retiform pattern of intense hemorrhage and the necrosis in the center of the lesion. From Robson K, Piette W. Adv. Dermatol. 1999;15:153–182, used with permission.

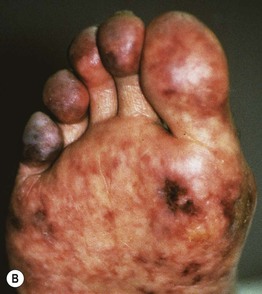

Fig. 18.3 Type I cryoglobulinemia in a patient with multiple myeloma (IgG type). Note the retiform purpura (A) and the areas of necrosis within the purpuric areas (B). Lesions favor the distal extremities, helices of the ears, and nose. Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD.

Fig. 18.4 Retiform purpura in antiphospholipid syndrome. Purpura and ischemia of the distal portion of the foot. The purpuric lesions have irregular borders (marked with ink). Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD.

Fig. 18.5 Atrophie blanche-like scarring in antiphospholipid syndrome. This patient had lupus erythematosus. Courtesy, Warren Piette, MD.

Fig. 18.6 Warfarin (Coumadin®) necrosis. Striking areas of retiform purpura with ischemic necrosis centrally on the pannus. Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD.

Fig. 18.7 Livedoid vasculopathy. Punched-out ulcers on the ankle as well as multiple stellate purpuric macules.

Fig. 18.8 Cholesterol emboli. A Livedo reticularis proximally on the thigh. B Both livedo reticularis and retiform purpura distally. C Purpura of the digits in ‘warfarin blue toe syndrome’. D Several irregularly shaped ulcers with eschars surrounded by retiform purpura. A, B, Courtesy, Norbert Sepp, MD; D, Courtesy, Kalman Watsky, MD.

Fig. 18.9 Intravascular B-cell lymphoma. The clinical presentation in this patient was retiform purpura and necrosis with livedo. Courtesy, Lucinda Buescher, MD.

– Classic ‘palpable purpura’: round red-purple papules that are occasionally targetoid, with a component of blanching erythema in early lesions; represents the most common presentation of cutaneous small vessel vasculitis (see Chapter 19; Fig. 18.1D).

Selected Microvascular Occlusion Syndromes (See Table 18.2)

Antiphospholipid Syndrome (APLS)

• Acquired systemic autoimmune disorder characterized by vascular thrombosis and/or pregnancy complications in the presence of elevated levels of antiphospholipid antibodies (Table 18.4).

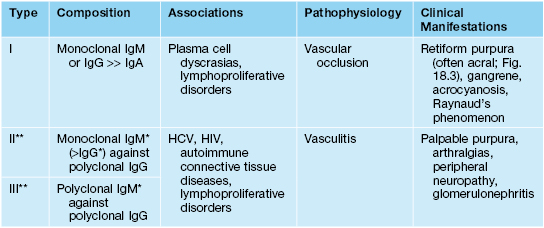

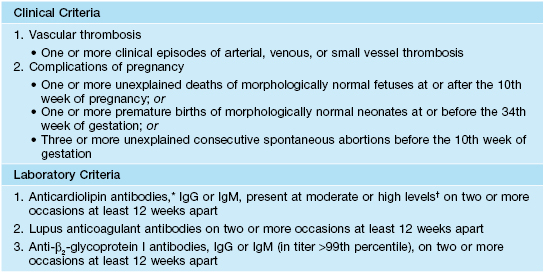

Table 18.4

2006 revised criteria for the antiphospholipid syndrome.

Definite diagnosis requires at least one clinical and one laboratory criterion.

* β2-glycoprotein I-dependent.

† Several thresholds exist for low versus moderate to high: (1) >40 international ‘phospholipid’ units; (2) 2–2.5× the median level of anticardiolipin antibodies (ACA); and (3) 99th percentile for ACA in the normal population.

• Predilection for young to middle-aged women (5 : 1 female : male ratio in adults) and often associated with systemic lupus erythematosus.

• Cutaneous findings can include livedo reticularis, retiform purpura progressing to cutaneous necrosis, leg ulcers, livedoid vasculopathy, Degos-like lesions, nail bed infarcts, superficial thrombophlebitis and anetoderma (see Figs. 18.4 and 18.5).

• Deep venous thrombosis and CNS disease are the most common extracutaneous manifestations; catastrophic APLS affecting multiple organ systems together with widespread retiform purpura occasionally occurs.

Livedoid Vasculopathy

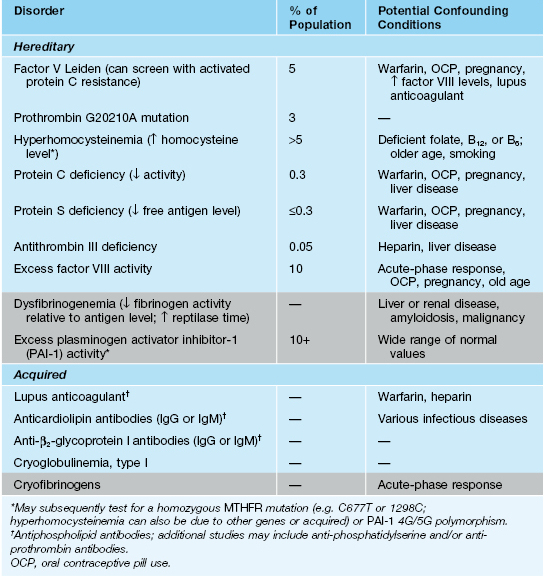

• Chronic condition that occurs primarily in young to middle-aged women, often with an underlying hypercoagulable state (Table 18.5).

Table 18.5

Evaluation for hypercoagulability.

Evaluation for entities in the rows shaded gray is often considered as second tier. The initial laboratory evaluation should also include a complete blood count with differential and platelet count, examination of a peripheral blood smear, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, activated partial thromboplastin time (PTT), and hepatic and renal function panels. Testing for antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) can be considered for patients with retiform purpura, as ANCA-positive vasculitides occasionally present with minimally inflammatory lesions.

• Recurrent development of hemorrhagic crusts resembling ground pepper and extremely painful, punched-out ulcers on the legs (especially the ankles); frequently arises within a background of retiform purpura ± livedo reticularis (see Fig. 18.7).

• The ulcers heal slowly, forming stellate, ivory-white, atrophic scars bordered by papular telangiectasias and hemosiderin pigmentation; such lesions, referred to as atrophie blanche, also occur in other settings such as venous hypertension, antiphospholipid syndrome (see Fig. 18.5), and cutaneous vasculitis.

• Rx: anticoagulant, antiplatelet, and fibrinolytic agents (especially if hypercoagulability).

Other Purpuric Disorders

Pigmented Purpuric Dermatoses (Capillaritis)

• Schamberg’s disease: most common form, occurring in both children and adults; recurrent crops of discrete yellow-brown patches containing pinpoint petechiae (‘cayenne pepper’) on the lower legs > thighs, buttocks, trunk, and arms (Fig. 18.10A); the yellow-brown color reflects deposits of hemosiderin, derived from extravasated RBCs, within the dermis.

Fig. 18.10 Schamberg’s disease versus petechiae and hemosiderin secondary to venous hypertension. A Discrete yellow-pink patches with superimposed petechiae in Schamberg’s disease. B Petechiae within a background of more diffuse hemosiderin deposition in the setting of venous hypertension, referred to as ‘stasis purpura.’ B, Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD.

• Purpura annularis telangiectodes (of Majocchi): favors adolescent girls and young women; expanding annular plaques with punctate telangiectasias and petechiae in their borders (Fig. 18.11).

Fig. 18.11 Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi. Annular plaques with ‘cayenne pepper’ petechiae in the border.

• DDx: ‘stasis purpura’ presenting as petechiae superimposed on diffuse hemosiderin deposition on the legs (see Fig. 18.10B); purpuric forms of allergic contact dermatitis, drug eruptions or mycosis fungoides; suction-induced purpura (e.g. with cupping), hypergammaglobulinemic purpura of Waldenström, angioma serpiginosum; for lichenoid variant: primarily small vessel vasculitis.

Hypergammaglobulinemic Purpura of Waldenström

• Recurrent crops of petechiae, purpuric macules, and/or palpable purpura (Fig. 18.12) on the lower extremities, often in young women with an autoimmune connective tissue disease (especially Sjögren’s syndrome).

For further information see Chs. 22 and 23. From Dermatology, Third Edition.