Pulmonary Function Tests

Pulmonary function tests (PFTs) help in the evaluation of the mechanical function of the lungs.1 They are based on researched norms, taking into account sex, height, and age. For example, there are predicted values for a male, age 65, who is 6 feet tall.2,3 Race and ethnic differences also play roles in the reference values and need to be taken into account for diagnostic and research purposes.4–6

Spirometry is the most useful and commonly available test of pulmonary function. Both pulmonologists and primary care physicians commonly use screening spirometry in their offices in order to assess patients and to evaluate the effectiveness of treatment being given to the patient.7

Patients with asthma and COPD make up a large portion of the primary care physician’s caseload. COPD is often diagnosed in the moderate to severe stage of the disease. The diagnosis of COPD can be made quite easily with spirometry, taking the patient’s symptoms and history into account. Smokers can be evaluated for early lung disease, and this can serve as a “teachable moment” for them to quit smoking.8

Yawn and colleagues (2007)9 compared the office spirometry interpretations of pulmonary experts with those of family physicians. They found agreement in 78% of the completed tests. In addition, following spirometry, changes were implemented in the management of 48% of patients. Of interest, there was closer correct interpretation of pulmonary functions between family physicians and pulmonologists in patients who had asthma, versus those with COPD.

Preoperative Pulmonary Evaluation

Preoperative pulmonary evaluation can predict postoperative pulmonary complications.10–12 As people are living longer lives, more older adults will be candidates for surgery. From 1980 to 1995 the rates of cardiovascular surgical procedures in patients over 65 tripled.13 In 1997 the performance of 10 of the most common surgical procedures in the United States totaled 1 in 350,0000 operations in the 65- to 84-year-old age group.14 Considering the comorbidities of an aging population and the concern about complications in older adults, a thorough preoperative pulmonary screening is recommended.11

Risk factors that contribute to postoperative complications include smoking, older age, obesity, poor health, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.11 Additional procedure-related risk factors include the site of surgery (abdominal, chest wall versus extremity, duration of surgery, and type of anesthesia or neuromuscular blockage).15

Office Spirometry to Improve Early Detection of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

The National Lung Health Education Program has recommended that office spirometry be used to screen for subclinical lung disease in adult smokers. For patients who are smokers or for any patients over 40 who have unexplained dyspnea, cough, wheezing, or excessive mucus, spirometric measurements can be considered another vital sign to measure during the routine physical examination, along with blood pressure and cholesterol levels.16,17

In a study of 35- to 70-year-old individuals visiting their general practitioners, patients were given a questionnaire on symptoms of obstructive lung disease.18 Spirometry was performed in patients with positive answers to the questions and in a random sample of 10% of the group. It was found that 42% of the newly diagnosed cases of obstructive disease would not have been detected without spirometry. The researchers concluded that office spirometry is essential in general practice and can be done by general practitioners who have training in the performance and interpretation of the pulmonary function tests. It is essential that there be good quality assurance and good training when these tests are performed in a general practitioner’s office. Studies have shown variability between the results of pulmonary function tests done in the office versus those done in a lab, so the results should not be considered interchangeable.19,20

Lung Volumes

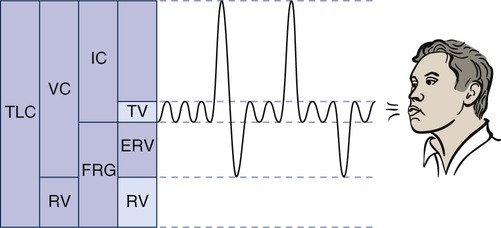

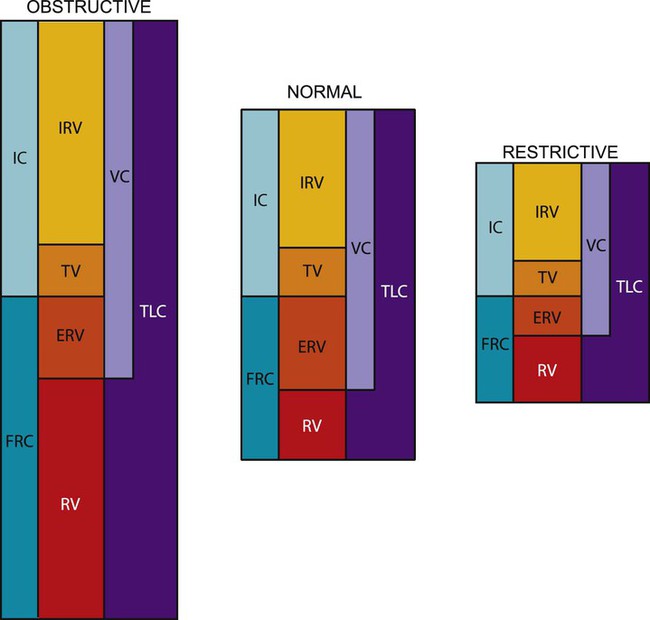

The lung has four volumes: TV, inspiratory reserve volume (IRV), expiratory reserve volume (ERV), and residual volume (RV) (Figure 9-1).

IRV is the maximum amount of air that can be inhaled above a normal inspiration.

IRV is the maximum amount of air that can be inhaled above a normal inspiration.

ERV is the maximum amount of air that can be expired after a normal exhalation.

ERV is the maximum amount of air that can be expired after a normal exhalation.

RV is the volume of gas that remains in the lungs at the end of a maximum expiration.

RV is the volume of gas that remains in the lungs at the end of a maximum expiration.

Changes in RV can help in the diagnosis of certain medical conditions. An increase in RV means that even with maximum effort, the patient cannot exhale excess air from the lungs. This results in hyperinflated lungs and indicates that certain changes have occurred in the pulmonary tissue, which in time may cause mechanical changes in the chest wall (e.g., increased [AP] diameter, flattened diaphragm). These changes may be reversible in patients with partial bronchial obstruction, such as young patients with asthma, or irreversible, as in patients with advanced emphysema. Restrictive lung disease can cause a decrease in residual volume, as can cancer of the lung, microatelectasis, or musculoskeletal impairment.21

Air Flow Measurements

Forced Expiration

Flow Volume Curve

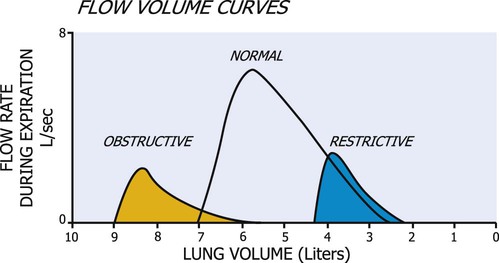

The flow volume curve is helpful in diagnosing lung disease because it is independent of effort. The curve in Figure 9-2 demonstrates that flow rises to a high value and then declines over most of expiration.22 In restrictive lung disease, the maximum flow rate is reduced, as is the total volume exhaled. In obstructive lung disease, the flow rate is low in relation to lung volume, and a scooped-out appearance is often seen (see Figure 9-2).

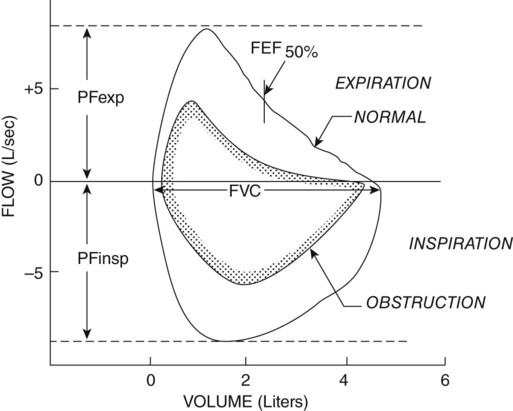

Another diagnostic test that uses forced expiration is the flow volume loop. It is a graphic analysis of the flow generated during a forced expiratory volume maneuver followed by a forced inspiratory volume maneuver (Figure 9-3). This graph offers a pictorial representation of data from many individual tests (e.g., peak inspiratory and expiratory flow rates, FVC, and FEV). The shape of the graph may also be helpful in diagnosing disease, because again there is a more scooped-out appearance in cases of obstructive disease.

Closing Volume and Airway Closure

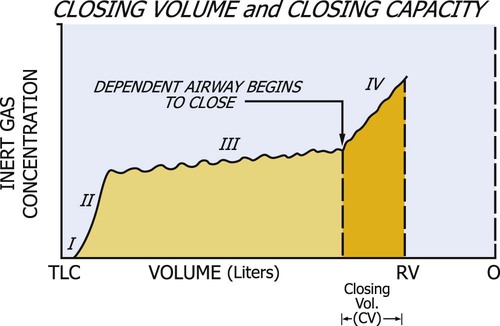

The assessment of closing volume is used to help diagnose small-airway disease. A test called the single-breath nitrogen (N2) washout is used for assessing closing volume and closing capacity of the small airways. In this test, the patient takes a single VC breath of 100% oxygen. During complete exhalation, the N2 concentration can be measured. The characteristic tracing of N2 concentration can be measured. The characteristic tracing of N2 concentration versus lung volume reflects the sequential emptying of differentially ventilated lung units, resulting in different expiratory concentrations of N2. Four phases can be identified (Figure 9-4). Phase I contains pure dead space and virtually none of the potential N2 from the RV. Phase II is associated with an increasing N2 concentration of a mixture of gas from the dead space and alveoli. The plateau in N2 concentration observed in phase III reflects pure alveolar gas emanating from the base and middle lung zones. Phase IV occurs toward the end of expiration and is characterized by an abrupt increase in N2 concentration. This high N2 concentration reflects the closure of airways at the base of the lungs and the expiration of gas from the upper lung zones, because in the single breath of 100% oxygen, less oxygen was initially directed to this area.

Diagnosis of Restrictive and Obstructive Lung Disease

Physicians use the results of pulmonary function tests to diagnose lung disease or characteristic components of lung disease such as bronchospasm. A restrictive component describes conditions that limit the amount of volume coming into the lungs (restriction to inspiration). An obstructive component generally relates to problems in exhalation air flows and characteristic patterns of obstruction, such as in the first second of expiration FEV1 measurement. Patients do not commonly have only one primary disease process but may have overlapping lung conditions.23 A diagnosis may read, “PFTs consistent with moderate emphysema with bronchospastic component; good response to bronchodilators.” A patient with an abnormal PFT is given a bronchodilator and retested. If there is a 15% to 20% increase in the PFT after bronchodilators are administered, they will be a recommended part of the patient’s medications. However, some patients are given a trial of bronchodilators, even if there is not such a dramatic response on PFTs.

A pictorial demonstration of the differences in obstructive and restrictive lung disease is shown in Figure 9-5. Disease has a marked effect on pulmonary function; yet TV usually remains 10% of total lung capacity until the disease is relatively severe. Physiological pulmonary reserves in both disease processes are limited and generally affect a patient’s response to exercise. Exercise is limited by the ventilatory status rather than by a cardiac end point. As obstructive lung disease progresses, TLC, FRC, and RV are markedly increased. In severe COPD, the increased FRC can compromise the VC. More energy is expended to breathe than that expended by a normal individual. This effect can be disproportionally increased with minimal amounts of activity. In restrictive lung disease, restriction of the chest wall or lung tissue can produce a decrease in TLC. A VC of 80% or less of predicted values for a patient is considered a diagnostic feature. A residual decline in FRC potentiates airway closure.

The phenomenon of closing volume in the lungs is particularly significant to physical therapists who prescribe breathing exercises and body positioning and can thereby alter pulmonary mechanics and gas exchange. These treatment interventions may have pronounced effects on lung volumes and airway closure.24 At low lung volumes (e.g., breathing at FRC, in the Trendelenberg position, and in lung disease) intrapleural pressures are generally less negative, and the pressure of dependent lung regions may equal or exceed atmospheric pressure. Intrapleural pressure is less negative because the lungs are less expanded and elastic recoil is decreased. As a result, airway closure is potentiated. In young individuals, closure is evident at RV; however, in older individuals, closure is observed at higher lung volumes, such as at FRC. Premature closure of the small airways results in uneven ventilation and impaired gas exchange with a given lung unit. Airway closure occurs more readily in chronic smokers and in patients with lung disease.

Aging has a significant effect on airway closure. With aging, a loss of pulmonary elastic recoil results in a loss of intrapleural negative pressure. In older individuals, therefore, airway closure occurs at higher lung volumes. For example, closure has been reported to occur at the age of 65 in the upright lung during normal breathing. In the supine position, where FRC is reduced, closure occurs at a significantly younger age (about age 44). In addition to the often compounding effect of age, the lung volume at which airway closure occurs increases with chronic smoking and lung disease and is changed with alterations in body position.25,26

Summary

Pulmonary functions change as a patient’s condition gets better or worse.27,28 There are normal declines in volumes and flows with aging, as well as with disease processes. Basic bedside spirometry is often done to assess a patient’s breathing mechanical ability and screen preoperatively to predict possible postoperative complications, especially in high-risk patients. Bedside screening can detect improvement or decline in a clinical status. In a patient with Guillain-Barré syndrome, as breathing becomes labored, the VC is monitored to determine whether a ventilator is needed. On the other hand, in a patient with obstructed airways, such as with cystic fibrosis, the pulmonary function tests will improve.29 In a patient with spinal cord injury or neuromuscular weakness, as strength improves, vital capacity increases. However, because of the lack of abdominal muscles, the flows may be reduced.