Clinical Evaluation and Assessment of the Cardiovascular and Pulmonary System

The Guide to Physical Therapist Practice provides a thorough patient management model.1 It identifies the key components necessary for a thorough examination and evaluation of the patient, tests and measures, identification of impairments, and interventions and outcomes that help the therapist in providing a multisystem examination and evaluation that will lead to appropriate treatment and achievement of optimal function and goals (see Figure 17-2).

History: Review and Interview

Medical Chart Review

Patient/Family Interview

1. Read the history and the physical and admission medical notes (i.e., the preadmission symptoms, past medical history)—this includes the physician’s notes and the nurse’s notes.

2. Read the most recent medical notes.

3. Scan the remainder of the chart.

4. Read any reports from medical specialists and consultants, such as pulmonologists, neurologists, or oncologists.

5. Review any pertinent lab tests, such as chest radiograph, arterial blood gases (ABGs), complete blood count (CBC), cardiac tests, CAT scans, and MRIs.

6. Review medications—in particular, pulmonary and cardiac drugs.

7. Review any procedures performed (e.g., surgery, intubation, chest tubes, NG tubes).

8. Review the psychosocial information (e.g., family, support systems, education, financial concerns, psychological issues, architectural barriers).

Details regarding the patient interview have been covered in Chapter 7. However, there are questions that should be posed to any patient, even if his or her primary condition is not cardiovascular and/or pulmonary. The patient whose primary referring impairment is musculoskeletal or neurological needs to have a screening of the cardiovascular and pulmonary system. The therapist should consider the following questions: What is the patient’s smoking history? Does the patient have a family history of premature coronary artery disease (i.e., a parent or sibling who had a myocardial infarction)? Can the symptoms presented also be signs of a cardiovascular or pulmonary illness? Does the patient have an active or a sedentary lifestyle? What activities precipitate the patient’s symptoms? Do these symptoms include breathlessness? Are there problems with airway clearance, congestion, etc.?

Topographic Anatomic Landmarks

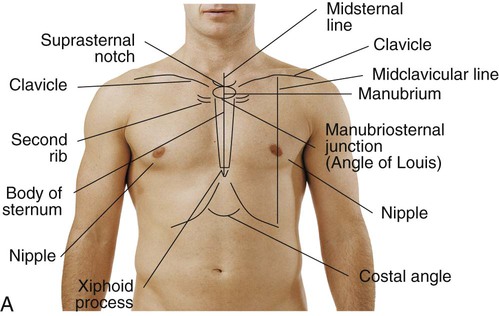

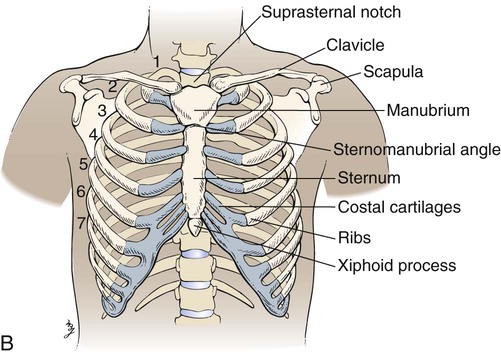

Key anatomic structures include the following:

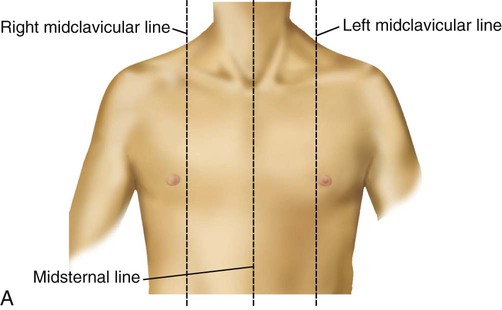

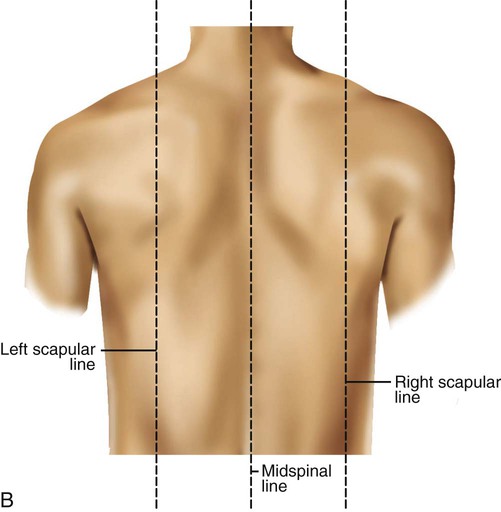

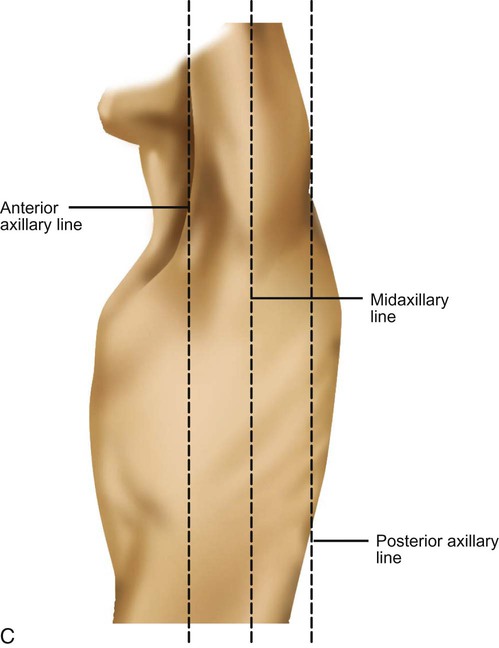

See Box 15-1 and Figure 15-1 for specific definitions and anterior and lateral views of the thorax. Imaginary topographic lines are used to more clearly describe any physical findings (e.g., location of surgical incisions, abnormal breath sounds, etc.; Figure 15-2).

The anterior view of the thorax has three vertical lines:

Midsternal line (MSL)—a vertical line bisecting the sternum

Midsternal line (MSL)—a vertical line bisecting the sternum

2 Midclavicular lines (MCLs)—parallel to the MSL, bisecting each clavicle; the borders of the lower lung cross the sixth ribs at the MCLs

2 Midclavicular lines (MCLs)—parallel to the MSL, bisecting each clavicle; the borders of the lower lung cross the sixth ribs at the MCLs

Laterally, there are also three vertical lines, originating in their respective axillary folds:

Visual Inspection

General Appearance

Does the patient appear comfortable? Is there any facial grimacing? Is the patient awake and alert or somnolent or disoriented? Is there any nasal flaring, wheezing, or pursed-lip breathing? (These are signs of respiratory distress. Nasal flaring can be defined as the outward movement of the nares with inspiration.2) Are the accessory muscles of respiration (i.e., sternocleidomastoid and trapezius) hypertrophied? How is the patient positioned? Is the patient resting comfortably or leaning forward over the bedside table and struggling for breath? What is the patient’s build—stocky, thin, or cachectic? Is the patient’s mobility limited? Can the patient sit unsupported? Should the assessment be performed in stages, allowing the patient to be supine and then to lie on each side? Is there any extra equipment in the patient’s surroundings? Is the patient using supplemental oxygen? Is the oxygen delivered through a nasal cannula or other device? What is the fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2)? Are there any monitoring lines, and where are they located? For instance, if an arterial line is present, is it placed in the radial or the femoral artery? Are there electrocardiogram (ECG) leads? Is it a hard line (directly connected to a monitor) or a telemetry line (communicating through radio transmitter)? Are there intravenous (IV) sites? Are they peripheral (antecubital) or central (subclavian or jugular)? Is there a urinary catheter? Are there chest tubes?

Skin

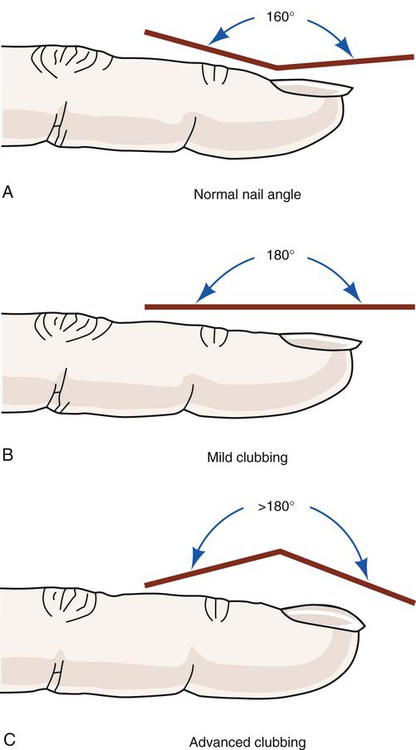

Are any scars, bruises, or ecchymoses observed? Are there reddened areas suggestive of prolonged pressure? Do the bony landmarks appear more prominent than usual? Are there any signs of trauma to the thorax or any other body parts? Does the skin appear edematous? Does this edema appear to limit joint motion? Are there any surgical incisions, new or old? Do these incisions appear to be healed or seem reddened and swollen? Is there evidence of clubbing of the digits? Digital clubbing can be defined as the loss of angle between the nail bed and the distal interphalangeal joint (Figure 15-3). The cause of clubbing is explained by a variety of theories, including increased perfusion secondary to hypoxemia with arterial desaturation, but this is not an exclusive phenomenon; clubbing has also been observed in nonpulmonary diseases such as hepatic fibrosis and Crohn’s disease.2–4

Jugular Venous Distention

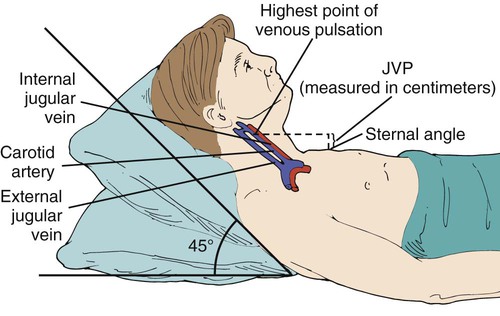

The jugular veins empty into the superior vena cava and reflect right-sided heart function. Right atrial pressure (RAP) is evident based on the extent to which the jugular venous pulse (JVP) can be visualized. The more superficial external jugular veins may be seen superior to the clavicles; the internal jugular veins, though larger, lie deep beneath the sternocleidomastoids and are less visible. Jugular venous distention (JVD) can be best seen when the patient lies with the head and neck at an angle of 45 degrees (Figure 15-4). The presence or absence of symmetry of JVD should be noted. The veins are distended bilaterally if there is a cardiac cause such as congestive heart failure (CHF). A unilateral distention is an indication of a localized problem.4

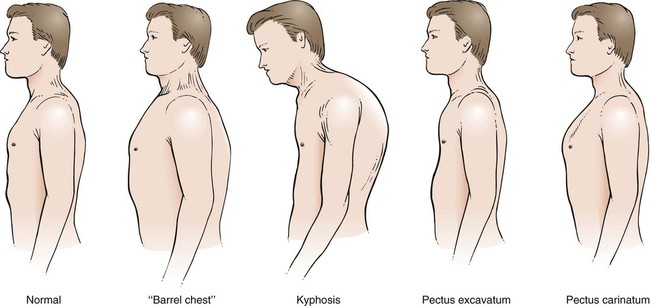

Chest Wall Configuration

Other structural defects are spinal deformities. These are best viewed posteriorly. Kyphoscoliosis is one example of how a posterior and lateral spinal deviation can limit chest wall and lung expansion. Another example is a patient with COPD, who usually has a forwardly tilted head and thoracic kyphosis (Figure 15-5).

Breathing Patterns

Respiratory rates normally range between 14 and 20 breaths per minute in adults (ages 15 and older). In children, the following ranges are normal: newborn, 30 to 60 breaths per minute; early childhood, 20 to 40 breaths per minute; late childhood, 15 to 25 breaths per minute.5

Other objective ways of measuring dyspnea (e.g., the Borg scale, the ventilator response index [VRI], the American Thoracic Society Dyspnea Scale, the Bog Scale of Perceived Exertion) are discussed in Chapter 8. Choosing a scale that the patient understands and can easily use will work best for identifying activities and interventions that cause more or less dyspnea. Later, patients can use the scale to self-monitor their dyspnea in relation to their activities and know when to increase or decrease activity secondary to dyspnea.

Auscultation

3. Knowledge of the different categories of lung sounds: normal, abnormal, adventitious breath sounds, and voice sounds

4. Knowledge of the various categories of heart sounds and murmurs

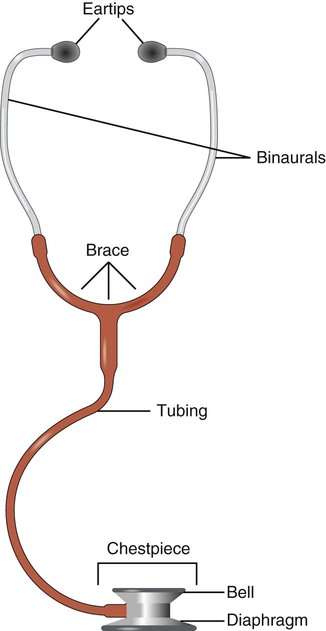

Stethoscope

A stethoscope need not be sophisticated to be effective. A physical therapist skilled in auscultation can use any basic stethoscope and be able to identify lung sounds. The stethoscope functions more as a filter to the extraneous noises than as an amplifier. A basic stethoscope consists of earpieces, tubing, and a chest piece. The bell portion of the chest piece assesses low-pitched sounds (i.e., heart sounds). The diaphragm portion discerns high-pitched sounds (Figure 15-6). The tubing should not be so long that sound transmission is dampened. An appropriate length is between 30 cm (12 inches) and 55 cm (21 to 22 inches). The earpieces should fit the physical therapist’s ears comfortably and allow the tuning out of external sounds. Another consideration is to position the earpieces anteriorly, or forward toward the ear canals. Warming the diaphragm before placing it on the patient’s skin is appreciated by the patient.

A study by Gurunga and colleagues evaluated the use of computer lung sound analysis as a diagnostic aid for auscultation. Their conclusion was that the interlistener automated variability was limited by the acuity of the individual listeners and that the use of the automated identification of lungs sounds may improve the overall sensitivity to more accurately pick up wheezes and crackles. The computerized lung sound analysis was 80% more specific and 85% more sensitive to wheezes and crackles. The authors concluded that their data are limited but may prove clinically promising in the future.6

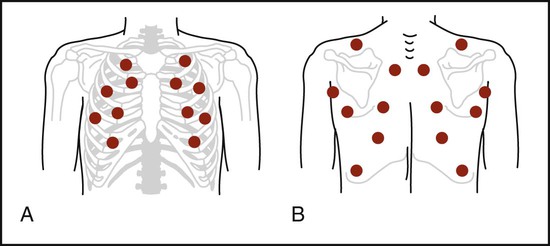

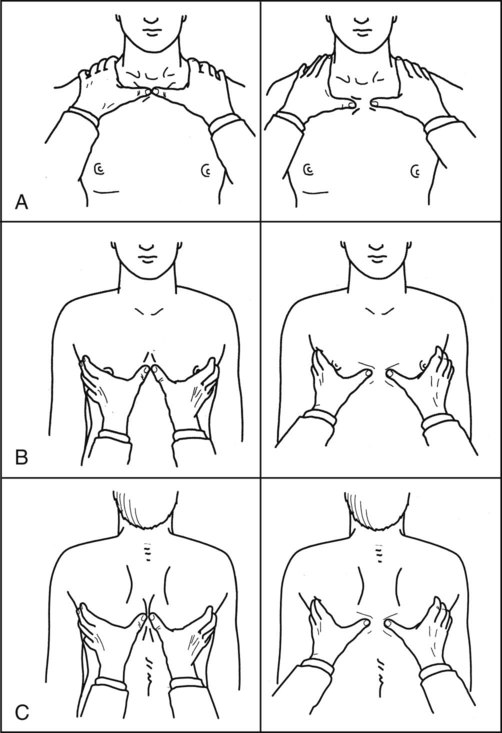

Technique

Environment is another element in the correct performance of auscultation. The room or cubicle should be as quiet as possible. Television and radio should be turned off, and any extraneous noises should be minimized or eliminated. This is especially important when auscultation is a new technique for the therapist. Clothing should be removed or draped so that it does not interfere in the assessment of the breath sounds. The patient should be in a sitting position, if possible, for lung sounds. The anterior, lateral, and posterior aspects of the chest should be auscultated both craniocaudally (apices to bases) and side to side (Figure 15-7). The physical therapist places the diaphragm on the patient’s skin so that it lies flat. The patient is instructed to breathe in and out through the mouth. A slightly deeper breath than tidal breathing is suggested. A minimum of one breath per bronchopulmonary segment allows for a comparison of the intensity, pitch, and quality of the breath sounds. Moving the diaphragm from one side to the other side while simultaneously moving it craniocaudally enables the therapist to compare the right side of the chest with the left side of the chest.

Chest Sounds

Chest sounds may be divided into the following categories.

1. Breath sounds—normal, abnormal, adventitious

2. Extrapulmonary sounds—pleural or friction rubs

3. Voice sounds—egophony, bronchophony, whispered pectoriloquy

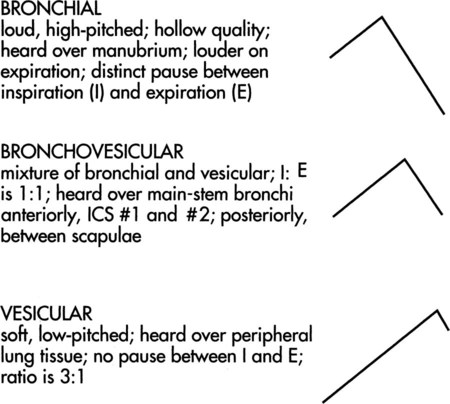

Breath Sounds

Bronchial sounds can be described as high-pitched and are heard in both the inspiratory and the expiratory phase. A distinguishing feature is the pause that exists between the inspiratory and expiratory phases (Figure 15-8). These sounds are also described as tracheal because their normal location is over the trachea. Bronchovesicular sounds are similar in that they are also high-pitched and have equal inspiratory and expiratory cycles. However, a differentiating feature is the lack of a pause (see Figure 15-8). Bronchovesicular sounds are heard best wherever the bronchi, or central lung tissue, are close to the surface. These areas are supraclavicular and suprascapular (the apices), as well as parasternal and interscapular (the bronchi). The ATS and ACCP, in their 1977 recommendations for pulmonary nomenclature, used the term bronchial to include both bronchial and bronchovesicular sounds. The difference is minor (the pause between the inspiratory and expiratory phases). This recommendation is meant to provide uniformity to lung-sound terminology. Vesicular breath sounds are heard over the remaining peripheral lung fields. These sounds have primarily an inspiratory component, with only the initial one-third of the expiratory phase audible. Their intensity is also softer because of the dampening effect of the spongy lung tissue and the cumulative effect of the air entry from numerous terminal bronchioles. The idea that vesicular sounds reflect air entry in the alveoli has been disproved. Thus, as the therapist auscultates from top to bottom, the breath sounds are quieter at the bases than at the apices. Infants and small children have louder, harsher breath sounds. This is as result of the thinness of the chest wall and the airways’ being closer to the surface.

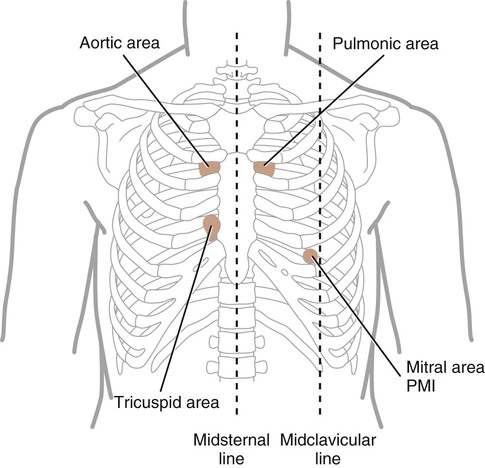

Heart Sounds

Aortic: second ICS, at right sternal border (RSB)

Aortic: second ICS, at right sternal border (RSB)

Pulmonic: second ICS, at left sternal border (LSB)

Pulmonic: second ICS, at left sternal border (LSB)

Normal Heart Sounds

The first heart sound (S1) signifies the closing of the atrioventricular valves. Its duration is 0.10 seconds; it is heard the loudest at the cardiac apex. The two components of S1 are tricuspid and mitral. Both the diaphragm and the bell of the stethoscope can be used to hear S1. Its loudness is enhanced by any condition in which the heart is closer to the chest wall (i.e., thin chest wall) or in which there is an increased force to the ventricular contraction (e.g., tachycardia resulting from exercise; Figure 15-9).

The second heart sound (S2) represents the closing of the semilunar valves and the end of ventricular systole. Its components are aortic and pulmonic. During expiration, these two components are not distinct because the time difference in the closure of the valves is less than 30 milliseconds. However, during inspiration, a splitting of S2 is audible. This physiologic split results from the increased venous return to the right heart secondary to the decreased intrathoracic pressure that occurs during inspiration. The pulmonic valve closure is delayed as the right ventricular systolic time is lengthened. A split S2 is heard commonly in children and young adults. The diaphragm of the stethoscope should be used to hear the split. The pulmonic component is the softer sound and is best heard at the LSB, in the second to fourth ICS. The two components may be heard best in the aortic and pulmonic areas, respectively. When the split is heard in both phases of respiration, an underlying cardiac abnormality is suspected. Causes may include right bundle branch block and pulmonary hypertension.2,7

Murmurs

Cardiac murmurs are the vibrations resulting from turbulent blood flow. They may be described based on position in cardiac cycle (systole, diastole), duration, and loudness. Systolic murmurs occur between S1 and S2; diastolic murmurs occur between S2 and S1. A continuous murmur starts in S1 and lasts through S2 for a portion or all of diastole. The loudness of a murmur is a factor of the velocity of blood flow and the turbulence created as it flows through a specific opening such as a valve. Grades I to VI are described in Table 15-1.

Table 15-1

| Grade | Loudness | Comments |

| I | Faint | Requires concentrated effort to hear |

| II | Faint | Audible immediately |

| III | Louder than II | Intermediate intensity |

| IV | Loud | Intermediate intensity; associated with palpable vibration (thrill) |

| V | Very loud | Thrill present |

| VI | Audible without stethoscope |

Murmurs that are grade III or higher are usually associated with cardiovascular pathology.

Mediate Percussion

Resonant: loud or high amplitude, low pitch, longer duration; heard over air-filled organs such as the lungs

Resonant: loud or high amplitude, low pitch, longer duration; heard over air-filled organs such as the lungs

Dull: low amplitude, medium to high pitch, short duration; heard over solid organs such as the liver

Dull: low amplitude, medium to high pitch, short duration; heard over solid organs such as the liver

Flat: high pitch, short duration; heard over muscle mass such as the thigh

Flat: high pitch, short duration; heard over muscle mass such as the thigh

Tympanic: high pitch, medium duration; heard over hollow structures such as the stomach

Tympanic: high pitch, medium duration; heard over hollow structures such as the stomach

Hyperresonant: very low pitch, prolonged duration; heard over tissue with decreased density (increased air-to-tissue ratio); abnormal in adults; heard over lungs with emphysema

Hyperresonant: very low pitch, prolonged duration; heard over tissue with decreased density (increased air-to-tissue ratio); abnormal in adults; heard over lungs with emphysema

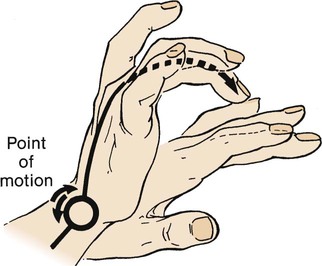

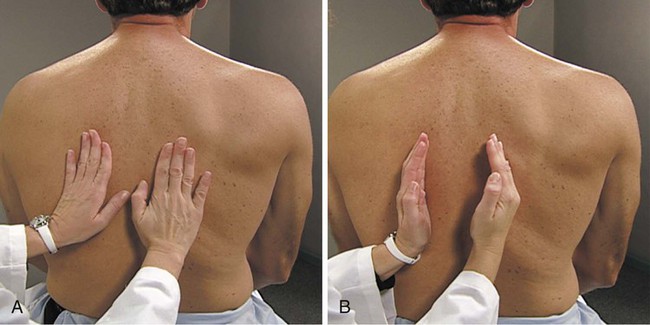

Technique

The middle finger of the nondominant hand is placed firmly on the chest wall in an intercostal space and parallel to the ribs. The top of the middle finger of the dominant hand strikes the distal phalanx of the stationary hand with a quick, sharp motion. The impetus of the blow comes from the wrist rather than the elbow and has been likened to that of a paddle ball player (Figure 15-10).2 As with auscultation, the therapist must follow the sequence of apices to bases and side to side so that comparisons can be made. This technique is not usually used in infants because percussion is too easily transmitted by a small chest.

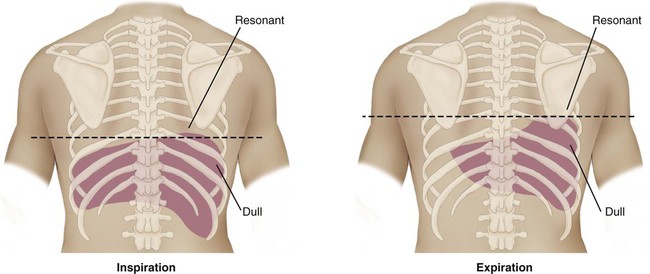

Diaphragmatic Excursion

Assessment of diaphragmatic movement can be made with mediate percussion. The patient is asked to breathe deeply and hold that breath. The lowest level of the diaphragm on maximal inspiration coincides with the lowest point where a resonant tone is heard. The patient is then asked to exhale, and mediate percussion is repeated. The lowest area of resonance now moves higher, as the diaphragm ascends with relaxation. The distance between these two points is described as the diaphragmatic excursion; the normal range is 3 to 5 cm (Figure 15-11). Diaphragmatic movement is decreased in patients with COPD.

Palpation

Chest Wall Excursion

The hyperinflation associated with COPD produces an increase in the anteroposterior diameter with a progressive loss of diaphragmatic excursion. Normal chest wall excursion is about 3.25 inches (8.5 cm) in a young adult between 20 and 30 years of age. One method is to use a tape measure at the level of the axilla and xiphoid. In a study of 120 normal subjects, ages ranging from 20 years to 70+ years, Kinney LaPier8 performed tape measure readings of subjects in a sitting or standing position at rest and at maximal inspiration (vital capacity) breaths. They found that subjects 20 to 29 years of age had 5.1 ± 6.2 CM excursion. In subjects 70 years and older, the excursion was only 2.5 ± 2.9 cm. The study found a definite decrease in chest wall excursion with age and recommends not utilizing chest wall excursion by tape measure in patients over 65.8

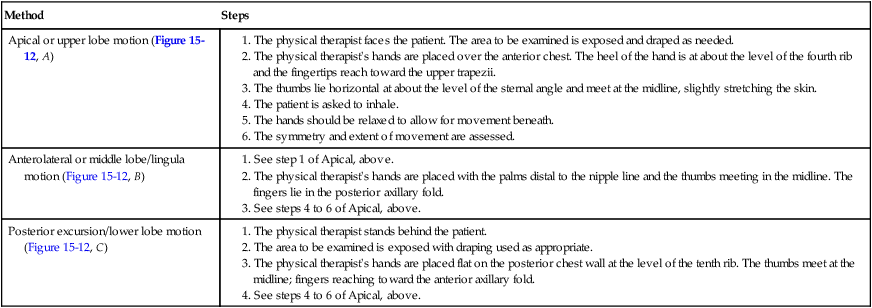

The most common method involves direct hand contact. This technique is performed in all planes and from top to bottom. Symmetry and extent of movement are noted. The procedures for this method are found in Table 15-2.

Table 15-2

Methods for Evaluating Thoracic Expansion

1. The physical therapist stands behind the patient.

2. The area to be examined is exposed with draping used as appropriate.

3. The physical therapist’s hands are placed flat on the posterior chest wall at the level of the tenth rib. The thumbs meet at the midline; fingers reaching toward the anterior axillary fold.

Tactile Fremitus

Spoken words produce vibration over the chest wall. Voice sounds have been previously discussed under auscultation. When the physical therapist’s hands are placed on the chest wall, the vibrations of spoken words can be felt; these are described as tactile fremitus. The presence or absence of tactile fremitus provides information about the density of the underlying lungs and thoracic cavity.2

Technique

Two methods can be used to evaluate for tactile fremitus (Figure 15-13). In the first technique, the therapist uses the palmar surface of one or both hands. The second method involves the use of the ulnar border of one hand. With both techniques, the sequence is, again, cephalocaudal and side to side. In either method, the next step is to ask that the patient speak a predetermined phrase. The two most commonly used phrases are “ninety-nine” and “one, two, three.” A light but firm touch is recommended.

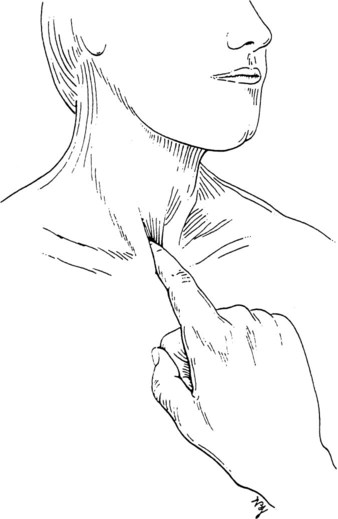

Tracheal Deviation

The trachea’s midline position can be examined anteriorly (Figure 15-14). The physical therapist places an index finger in the medial aspect of the suprasternal notch. This is repeated on the opposite side. An equal distance between the clavicle and the trachea should exist bilaterally. Tracheal deviation may be caused by a pneumothorax, atelectasis, or a tumor. Whether the deviation is ipsilateral or contralateral depends on the underlying cause. A right pneumothorax or pleural effusion deviates the trachea away from the affected side (i.e., the left); a left lower lobe atelectasis, however, deviates the trachea toward the affected side (i.e., the left).

Case Studies

Case Study 15-1

Visual inspection: Forward head and neck, protracted shoulders, kyphotic posture, and increased anteroposterior diameter are present; the patient appears thin and fatigued; respiratory rate 24, use of accessory muscles observed; the patient has an effective and wet cough producing green thick mucus

Visual inspection: Forward head and neck, protracted shoulders, kyphotic posture, and increased anteroposterior diameter are present; the patient appears thin and fatigued; respiratory rate 24, use of accessory muscles observed; the patient has an effective and wet cough producing green thick mucus

Auscultation: Decreased breath sounds with scattered crackles throughout all lung fields, especially over right posterior upper lobe and right middle lobe

Auscultation: Decreased breath sounds with scattered crackles throughout all lung fields, especially over right posterior upper lobe and right middle lobe

Palpation: Limited chest wall excursion (CWE), especially laterally on right

Palpation: Limited chest wall excursion (CWE), especially laterally on right

Mediate percussion: Dull over right middle and lower chest, especially laterally

Mediate percussion: Dull over right middle and lower chest, especially laterally

The evaluation component utilizes the above findings to identify the appropriate outcomes and treatment interventions. Based on the acuity of the examination, acute exacerbation of cystic fibrosis may be the diagnosis. The focus may be on secretion clearance and identification of the most appropriate airway clearance techniques. Would the high-frequency chest oscillations (ThAIRapy Vest) or manual techniques of chest percussion, vibration/shaking, and specific postural drainage positions be the choice for this patient? Scheduling airway clearance techniques and coordination treatments with respiratory therapy and inhaled medications is indicated as well. Ongoing daily reexamination will determine whether the treatment interventions need to be modified or continued as is. The patient’s home exercise and airway clearance program should be reevaluated to prevent recurrence. The use of a daytime device such as Acapella or Flutter or other easy-to-use equipment may be helpful to enhance the patient’s airway clearance program (see Chapter 21).

For more information about musculoskeletal issues in people with cystic fibrosis, see the article by Massery (2005).9

Case Study 15-2

Visual inspection: Tachypnea; RR 44; I : E ratio 1 : 1; weak, shallow cough

Visual inspection: Tachypnea; RR 44; I : E ratio 1 : 1; weak, shallow cough

Auscultation: Bronchial over right midanterior chest; egophony also present

Auscultation: Bronchial over right midanterior chest; egophony also present

Mediate percussion: Dull over affected area

Mediate percussion: Dull over affected area

Palpation: Trachea midline, markedly decreased CWE on right side

Palpation: Trachea midline, markedly decreased CWE on right side

Case Study 3

Visual inspection: RR 30; I : E ratio 1 : 2; epidural catheter for pain control; effective dry cough

Visual inspection: RR 30; I : E ratio 1 : 2; epidural catheter for pain control; effective dry cough

Auscultation: Absent breath sounds halfway up left lower lateral chest wall

Auscultation: Absent breath sounds halfway up left lower lateral chest wall

Mediate percussion: Flat over left lower lateral chest wall

Mediate percussion: Flat over left lower lateral chest wall

Palpation: Trachea deviated to right; decreased CWE on left; range of motion of left shoulder joint limited in flexion and abduction at about 90 degrees maximum; no preadmission shoulder limitations

Palpation: Trachea deviated to right; decreased CWE on left; range of motion of left shoulder joint limited in flexion and abduction at about 90 degrees maximum; no preadmission shoulder limitations

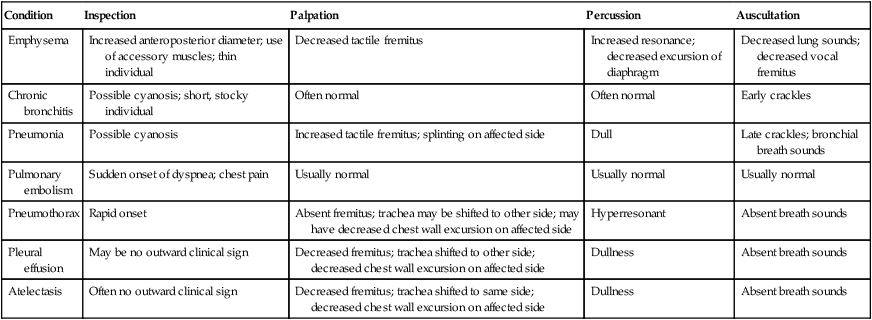

Table 15-3 presents differentiation of diagnoses by the elements of a chest physical examination.

Table 15-3

Differentiation of Common Pulmonary Conditions

| Condition | Inspection | Palpation | Percussion | Auscultation |

| Emphysema | Increased anteroposterior diameter; use of accessory muscles; thin individual | Decreased tactile fremitus | Increased resonance; decreased excursion of diaphragm | Decreased lung sounds; decreased vocal fremitus |

| Chronic bronchitis | Possible cyanosis; short, stocky individual | Often normal | Often normal | Early crackles |

| Pneumonia | Possible cyanosis | Increased tactile fremitus; splinting on affected side | Dull | Late crackles; bronchial breath sounds |

| Pulmonary embolism | Sudden onset of dyspnea; chest pain | Usually normal | Usually normal | Usually normal |

| Pneumothorax | Rapid onset | Absent fremitus; trachea may be shifted to other side; may have decreased chest wall excursion on affected side | Hyperresonant | Absent breath sounds |

| Pleural effusion | May be no outward clinical sign | Decreased fremitus; trachea shifted to other side; decreased chest wall excursion on affected side | Dullness | Absent breath sounds |

| Atelectasis | Often no outward clinical sign | Decreased fremitus; trachea shifted to same side; decreased chest wall excursion on affected side | Dullness | Absent breath sounds |

Modified with permission from Swartz MH: Textbook of physical diagnoses—History and examination, ed 2, Philadelphia, 1994, WB Saunders.