Pulmonary Complications in the Immunocompromised Host

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS)

Infectious Complications of AIDS

Pneumocystis jiroveci Pneumonia

A general discussion of Pneumocystis as a respiratory pathogen was given in Chapter 25. In patients with AIDS, onset of the disease is often more indolent than in immunosuppressed patients without AIDS. Fever, cough, and dyspnea are the usual symptoms bringing the patient to medical attention. The typical chest radiograph shows diffuse interstitial or alveolar infiltrates. Often the lung fields look hazy, a pattern that may be difficult to characterize specifically as either interstitial or alveolar and commonly described as looking like “ground glass” (see Fig. 25-3). However, atypical radiographic presentations are clearly recognized with documented Pneumocystis pneumonia, including even the finding of a normal chest radiograph. High-resolution computed tomographic (CT) scanning is particularly sensitive for demonstrating subtle changes associated with Pneumocystis pneumonia and generally shows abnormal results even in patients with a normal chest radiograph.

Fungal Infection

Histoplasmosis and coccidioidomycosis, fungal infections that occur in specific endemic regions, are described in detail in Chapter 25. In patients with AIDS, pulmonary involvement with these organisms is most commonly a manifestation of disseminated disease that resulted either from reactivation of previous disease or from progressive primary infection. Consequently, histoplasmosis and coccidioidomycosis are seen primarily but not exclusively in their respective endemic areas. As is the case in patients without AIDS, amphotericin B (or an oral azole such as itraconazole) is the primary agent used to treat either of these infections.

Noninfectious Complications of AIDS

Pulmonary Vascular Disease

A number of cases of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) in patients with HIV infection have been reported. Although the association is believed to be a true rather than a coincidental relationship, no clear mechanistic or pathophysiologic explanation is known. The histopathology and clinical features are typically similar to those of idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (IPAH), but the disease may have a more rapid progression than is generally seen in patients without HIV infection. Treatment is similar to that of IPAH (see Chapter 14), but use of endothelin-1 receptor antagonists is frequently problematic because of concomitant hepatic disease or concerns about drug interactions. Antiretroviral therapy is generally indicated as part of the therapeutic approach.

Pulmonary Complications in Non-HIV Immunocompromised Patients

Organ Transplant Recipients

Solid Organ Transplantation

Lung transplantation is increasingly performed to treat a variety of end-stage lung diseases (see Chapter 29). In addition to the effects of immunosuppressive medications, the immunologic milieu in the transplanted lung is quite abnormal, leading to an increased risk of pulmonary infections of a variety of types. The propensity of specific organisms to cause infections in the post–lung transplant period varies somewhat during the time course following transplantation.

Primary Immunodeficiencies

Primary immunodeficiencies are genetic disorders that result in dysfunction of one or more limbs of the immune response. Antibody deficiencies may be due to conditions such as X-linked agammaglobulinemia, common variable immunodeficiency, or immunoglobulin (Ig)G subclass deficiencies, and the diagnosis is usually confirmed by quantitative measurement of immunoglobulins. Patients with antibody deficiencies may suffer from recurrent sinopulmonary infections, most commonly from encapsulated bacteria such as S. pneumoniae and H. influenzae. Increased rates of infection with Mycoplasma pneumoniae have also been reported. Diffuse bronchiectasis may develop as a result of repeated infections (see Chapter 7), and if the bronchiectasis is sufficiently severe, hypoxemia and cor pulmonale may ultimately ensue. Amelioration of many manifestations of antibody deficiencies may be possible by regular administration of intravenous human IgG.

Diagnostic Evaluation of Pulmonary Infiltrates in Non-HIV Immunocompromised Patients

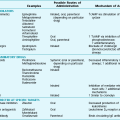

The spectrum of infectious and noninfectious causes of pulmonary infiltrates in the immunosuppressed host is given in Table 26-1. Although fungi and other relatively unusual types of organisms are commonly thought to be the major causes of infiltrates in patients receiving treatment for malignancy, bacterial pneumonia is actually the most frequent problem in this setting. Neutropenia is the primary predisposing factor for bacterial pneumonias, which frequently are due to gram-negative rods or Staphylococcus.

Table 26-1

CAUSES OF PULMONARY INFILTRATES IN THE IMMUNOCOMPROMISED HOST

INFECTIONS

Bacteria

Viruses

Fungi

Protozoa

Toxoplasma gondii (rare)

PULMONARY EFFECTS OF THERAPY

Pulmonary hemorrhage

Heart failure

Disseminated malignancy

Nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis (no defined etiology)

Common noninfectious diagnoses are interstitial lung diseases due to side effects of radiation therapy or a variety of chemotherapeutic agents (see Chapter 10). Among lung transplant recipients, development of pulmonary infiltrates and fever is highly suggestive of an infectious pneumonia, although acute lung transplant rejection can present in a similar fashion. Heart failure (often secondary to cardiac toxicity from chemotherapeutic agents), pulmonary dissemination of the underlying malignancy, and hemorrhage into the pulmonary parenchyma are other causes of infiltrates that can closely mimic infectious etiologies. In many circumstances, an interstitial inflammatory process can be proved histologically, but no definite cause can be identified. These cases often are diagnosed as nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis, with the realization that neither the pathology nor the clinical history provides a specific etiologic diagnosis.

Infectious Pulmonary Complications of HIV Infection

Anandaiah, A, Dheda, K, Keane, J, et al. Novel developments in the epidemic of human immunodeficiency virus and tuberculosis coinfection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:987–997.

Baughman, RP. Cytomegalovirus: the monster in the closet? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156:1–2.

Beck, JM, Rosen, MJ, Peavy, HH. Pulmonary complications of HIV infection. Report of the fourth NHLBI workshop. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:2120–2126.

Boiselle, PM, Crans, CA, Kaplan, MA, et al. The changing face of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in AIDS patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;172:1301–1309.

Bozzette, SA, Finkelstein, DM, Spector, SA, et al. A randomized trial of three antipneumocystis agents in patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:693–699.

Burman, WJ, Jones, BE. Treatment of HIV-related tuberculosis in the era of effective antiretroviral therapy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:7–12.

Girard, P-M. Discontinuing Pneumocystis carinii prophylaxis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:222–223.

Hirschtick, RE, Glassroth, J, Jordan, MC, et al. Bacterial pneumonia in persons infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:845–851.

Hull, MW, Phillips, P, Montaner, JS. Changing global epidemiology of pulmonary manifestations of HIV/AIDS. Chest. 2008;134:1287–1298.

Johnson, MD, Decker, CF. Tuberculosis and HIV infection. Dis Mon. 2006;52:420–427.

Kovacs, JA, Gill, VJ, Meshnick, S, et al. New insights into transmission, diagnosis, and drug treatment of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. JAMA. 2001;286:2450–2460.

Kovacs, JA, Masur, H. Prophylaxis against opportunistic infections in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1416–1429.

Masur, H, Kaplan, JE, Holmes, KK. editors: Guidelines for preventing opportunistic infections among HIV-infected persons—2002. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:435–477.

Minamoto, GY, Rosenberg, AS. Fungal infections in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Med Clin North Am. 1997;81:381–409.

Rigsby, MO, Curtis, AM. Pulmonary disease from nontuberculous mycobacteria in patients with human immunodeficiency virus. Chest. 1994;106:913–919.

Rosen, MJ, Narasimhan, M. Critical care of immunocompromised patients: human immunodeficiency virus. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(9 Suppl):S245–S250.

Thomas, CF, Limper, AH. Pneumocystis pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2487–2498.

Wolff, AJ, O’Donnell, AE. Pulmonary manifestations of HIV infection in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Chest. 2001;120:1888–1893.

Noninfectious Complications of HIV Infection

Aboulafia, DM. The epidemiologic, pathologic, and clinical features of AIDS-associated pulmonary Kaposi’s sarcoma. Chest. 2000;117:1128–1145.

Barnett, CF, Hsue, PY, Machado, RF. Pulmonary hypertension: an increasingly recognized complication of hereditary hemolytic anemias and HIV infection. JAMA. 2008;299:324–331.

Bazot, M, Cadranel, J, Benayoun, S, et al. Primary pulmonary AIDS-related lymphoma. Radiographic and CT findings. Chest. 1999;116:1282–1286.

Cadranel, J, Mayaud, C. Intrathoracic Kaposi’s sarcoma in patients with AIDS. Thorax. 1995;50:407–414.

Mehta, NJ, Khan, IA, Mehta, RN, et al. HIV-related pulmonary hypertension. Analytic review of 131 cases. Chest. 2000;118:1133–1141.

Mesa, RA, Edell, ES, Dunn, WF, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus infection and pulmonary hypertension: two new cases and a review of 86 reported cases. Mayo Clin Proc. 1998;73:37–45.

Stebbing, J, Sanitt, A, Nelson, M, et al. A prognostic index for AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Lancet. 2006;367:1495–1502.

Pulmonary Disease Associated with Non-HIV Immunodeficiency

Ahmad, S, Shlobin, OA, Nathan, SD. Pulmonary complications of lung transplantation. Chest. 2011;139:402–411.

Crum, NF, Lederman, ER, Wallace, MR. Infections associated with tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonists. Medicine (Baltimore). 2005;84:291–302.

Dukes, RJ, Rosenow, EC, III., Hermans, PE. Pulmonary manifestations of hypogammaglobulinemia. Thorax. 1978;33:603–607.

Edgar, JD. T cell immunodeficiency. J Clin Pathol. 2008;61:988–993.

Eslamy, HK, Newman, B. Pneumonia in normal and immunocompromised children: an overview and update. Radiol Clin North Am. 2011;49:895–920.

Fishman, JA. Infection in solid-organ transplant recipients. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2601–2614.

Kang, EM, Marciano, BE, DeRavin, S, et al. Chronic granulomatous disease: overview and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:1319–1326.

Kotloff, RM, Thabut, G. Lung transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:159–171.

Mayaud, C, Cadranel, J. A persistent challenge: the diagnosis of respiratory disease in the non-AIDS immunocompromised host. Thorax. 2000;55:511–517.

Panoskaltsis-Mortari, A, Griese, M, Madtes, DK, et al. American Thoracic Society Committee on Idiopathic Pneumonia Syndrome: An official American Thoracic Society research statement: noninfectious lung injury after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: idiopathic pneumonia syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:1262–1279.

Perfect, JR. The impact of the host on fungal infections. Am J Med. 2012;125(1 Suppl):S39–S51.

Ramos-Casals, M, Perez-Alvarez, R, Perez-de-Lis, M, et al. BIOGEAS Study Group: Pulmonary disorders induced by monoclonal antibodies in patients with rheumatologic autoimmune diseases. Am J Med. 2011;124:386–394.

Rañó, A, Agusti, C, Sibila, O, et al. Pulmonary infections in non-HIV-immunocompromised patients. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2005;11:213–217.

Rosenow, EC, III., Wilson, WR, Cockerill, FR, III. Pulmonary disease in the immunocompromised host: I. Mayo Clin Proc. 1985;60:473–487.

Shelhamer, JH, Gill, VJ, Quinn, TC, et al. The laboratory evaluation of opportunistic pulmonary infections. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124:585–599.

Talbot, EA, Hicks, CB. Opportunistic thoracic infections. Bacteria, viruses, and protozoa. Chest Surg Clin North Am. 1999;9:167–192.

Tsiodras, S, Samonis, G, Boumpas, DT, et al. Fungal infections complicating tumor necrosis factor alpha blockade therapy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:181–194.

Waite, S, Jeudy, J, White, CS. Acute lung infections in normal and immunocompromised hosts. Radiol Clin North Am. 2006;44:295–315.

Walsh, FW, Rolfe, MW, Rumbak, MJ. The initial pulmonary evaluation of the immunocompromised patient. Chest Surg Clin North Am. 1999;9:19–38.

Wilson, WR, Cockerill, FR, III., Rosenow, EC, III. Pulmonary disease in the immunocompromised host. II. Mayo Clin Proc. 1985;60:610–631.