Chapter 190 Psychosocial Aspects and Work-Related Issues Regarding Lumbar Degenerative Disc Disease

Over previous centuries, back pain was poorly understood, and the affected, unfortunate patients were left to go about life and deal with their pain. More recently, it was proposed that pain was a direct indication of tissue injury and that repair of the injuring mechanism would relieve the pain. It is now understood that some components of low back disability may be a manifestation of actual physical pain, but the vast majority of this may be due to the psychological reaction to pain. In his review in 1991, Waddell1 considered the history of low back pain and disability. Interestingly, the first reported case of low back pain was from the Edwin Smith papyrus in 1500 bce, and not much has changed about back pain since then. The first idea that back pain came from spine and nervous system dysfunction came from Brown in 1828.2 After the industrial revolution, the concept of back pain due to injury became quite popular.3 Changes in the law allowed individuals to benefit from compensation due to work injuries. By 1915, King4 declared that “pain in the back as a result of injury is the most frequent affection for which compensation is demanded from the casualty company.” This has certainly been expanded since that time, and low back pain continues to be one of the most common reasons for loss of work today.

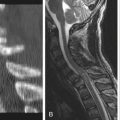

The history of the development of various specialties in the medical profession also tells an interesting story with regard to low back pain. Development of the fields of orthopaedics and neurosurgery in the early 20th century has had a great impact on the role of back pain as a disease process today. As orthopaedics advanced as a specialty, the concept of rest for treatment of back pain came about. Prior to this, patients who had pain remained at work, and the concept of pain as a disability was unheard of. This was followed by the discovery of the ruptured disc by Mixter and Barr5 in 1934, which led to the revolutionary treatment of low back pain and sciatica with surgery. This trend has remained today with much controversy surrounding the treatment of back pain and discogenic disease by surgical means.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Studies regarding the epidemiology of low back pain are highly variable. This is not surprising—it is a condition that is highly specific to each individual patient. Survey studies are difficult because one patient’s perception of pain may be quite different than that of another. The incidence of developing a new episode of back pain has been estimated as low as 4% and as high as 93%.6–9 On the basis of larger longitudinal studies, this incidence has been estimated to be much lower, between 3% and 5% for episodes where patients sought medical attention. The incidence of back pain that did not require professional medical care was much higher, at 30%.7 Prevalence is difficult to study due to variance among study populations and the different factors that may affect the development of low back pain. Studies estimate that 15% to 20% of adults experience memorable low back pain within 1 year and up to 80% experience such pain over a lifetime.10–13

In terms of age, back problems do not necessarily occur more frequently during the third to fifth decades. When they do, however, they are certainly more often related to claimed disability during this period. These are the prime working years, where low back pain leads to the greatest disability and days off work. Interestingly, the symptoms of low back pain do not become worse with age-related degeneration of intervertebral discs.1,14–17 Back pain in the elderly is thought to be one of the most important factors to affect the individual state of health.18 Similar to younger adults, the prevalence of back pain in patients older than 65 years of age is 13% to 49%,19 but this pain seems to be more episodic and intermittent with a lesser occurrence of chronic pain.20 Despite the relatively high prevalence of abnormal curvature of the spine in adolescents, the chance of these children presenting with low back pain is quite low. Some studies suggest that the peak age for development of back pain in children is 13 to 14 years and that beyond this age, the risk factors for developing back pain in adults also apply in children.21–23

Risk factors for the development of low back pain are demographic, physical, socioeconomic, psychological, and occupational factors. Many studies of these risk factors are small and include only self-reports of the variables. A review by Hildebrandt discusses 55 personal factors and 24 occupational factors that have been linked to low back pain.24 Many studies have looked at the relationship between socioeconomic status and level of education and the development of back pain. The association seems to be not so much with the incidence of pain but with the ability to adjust to pain. The incidence of disability from back pain appears to be 22 to 25 times higher in patients with less than 7 years of education compared with those with college degrees.25

Observations Regarding Low Back Pain and Disability

First, it is important to differentiate between pain and disability. Both are related in that they are generally subjectively relayed by the patient and are not viewed the same in any two patients. There is no objective measure for either of these disorders. Disability is related to the patient’s perceptions and attitudes about pain26,27 and may be based on avoidance based on previous painful experiences.1,28,29 Many people live with low back pain, and few patients view this condition as a disability.

It is also useful to discuss the difference between acute and chronic pain. Acute pain often bears a close relationship to an inciting event and may be thought to stem directly from tissue injury. Chronic pain, on the other hand, is often a behavioral adaptation of an individual who may or may not have had an initial injury. This bears very little relationship to physical injury and is very difficult to treat by medical and surgical means. The failed back syndrome is indeed closely related to this concept. Chronic pain becomes a syndrome of emotional distress, depression, and disease conviction.1 If these patients are taken to surgery under the misconception that their pain is actually related to tissue injury, they are virtually never cured and are often made worse. Surgery in these patients also plays into the “sick role” and gives them further reason to take time off work and to claim that they are disabled. These patients often clog pain clinics and spine clinics and place a heavy burden on the health-care system.

Despite low back pain and sciatica taking center stage in many medical circles today, there is no evidence that the biology of the problem has changed at all over the years. Back pain is the same as it always has been. It is low back disability that is a new concept. Ninety percent of patients with low back pain become better within 6 weeks in spite of technologically advanced medical and surgical care, or interestingly, no care at all.1,15,30,31 This is likely a product of the explosion in the size and complexity of the health-care systems of Western countries and individuals’ perceptions that the abilities of modern health care should be able to end pain. Physicians bear some responsibility in this regard because it is they who certify patients with pain to be excused from work, thereby feeding into the concept of low back disability.

Perhaps the most referenced expert to publish on low back pain and disability is Gordon Waddell. In his book The Back Pain Revolution,32 he discusses his time spent in Oman. At the time of his writing, Oman was an emerging, primarily developing country. In the mid-1980s, new oil money soon brought modern medical treatments to this country. At the time, patients with back pain flooded into the newly established clinics seeking treatment for their pain. These patients had very similar problems with similar etiology to patients in developed Western countries. The interesting part is that nearly none of them were off work or “disabled” as a result of their pain. Waddell’s observation was that the patients who were able to escape the confines of their country to have “modern” medical procedures in other countries became disabled after surgery at a much higher rate than those who did not have access to modern medical care. This is another illustration that suggests that low back pain is nothing new but that low back disability is largely a product of modern Western medicine.

Breakdown of the Disease Model of Illness

Chronic low back pain probably is better considered in the context of a different disease model, the biopsychosocial model. This model stresses the integration of the mind-body continuum, which has been proposed by philosophers since before science was born. This suggests that it is not only the responsibility of the physician to treat the body but also to assist the patient in adjusting to their illness and coping with it mentally. The gate theory of pain and experience with psychosurgery both support the assertion that pain perception requires both sensory and emotional components and can be modified by mental, emotional, or sensory mechanisms.33

These concepts are very solidly related to the diagnosis and treatment of low back pain. As it turns out, many patients are not satisfied with an office visit without the establishment of a diagnosis based on real pathology. Disc disease has become so popular and common, and patients may be given the nominal diagnosis of disc prolapse without any signs of nerve root compression or radiographic evidence. It is not long until this nominal diagnosis is confused with real disease pathology, and the patient receives the label of discogenic low back pain. These patients may eventually end up being treated with surgery and then bouncing from clinic to clinic when this operation fails. Clinics are clogged with these patients, making it difficult to care for patients with real pathology. Making matters worse, patients often go from clinic to clinic until a diagnosis is made, leaving an incentive for physicians to make nominal diagnoses or risk losing patients. Indeed, a large study of the indications for spinal surgery in the mid-1980s showed that surgical decision making was often driven by duration and severity of pain and disability, patients’ illness behavior, and failure of conservative treatment.34 As might be expected, the success rate for surgical treatment based on a nominal diagnosis is at best 30% to 40%. Interestingly, nearly every study in the past 50 years has shown that the presence of a psychiatric disease as an extremely poor predictor for good surgical outcome.1,35–43 Thus, the responsible surgeon must use the history and physical examination to tease out signs of psychiatric imbalance and consider this carefully prior to proceeding with surgery.

Work-Related Issues

Since complaints of low back pain hit a peak during the working years, it is essential to discuss this process as it relates to time off work. First, this problem is most prominent in the group of patients with chronic low back pain. In a study by Volinn et al., 2% of workers eligible for industrial insurance filed a claim for back pain in 1 year. Of those, 12% were off work for 90 days or more, consuming more than 88% of the wage and medical compensation paid by insurance.44 This same study found that the complaints of back sprain and pain were closely related to workplace dissatisfaction and monotonous job tasks. The medical costs largely involved surgery and hospital stays for “medical back problems.” One study of Medicare patients found that 71% of these “medical back” hospitalizations were inappropriate.45 In a review of low back pain and health care utilization, Volinn et al. suggest that the level of both cognitive and economic investment in low back pain drives therapy.46 Only when further knowledge and education of outcomes regarding the treatment of low back pain become available, and third party payers invoke more stringent guidelines for what will and will not be reimbursed, will the trends in surgical and medical management change.

Indeed, there is no good evidence in the literature that rest improves low back pain or even sciatica. This is a somewhat difficult area to study without a high degree of bias, and as one might expect, the major studies are methodologically flawed. Even in the majority of these studies, it was found that shorter periods of rest were more beneficial (or less harmful) than longer periods.1 Along with these findings, there have been no studies to suggest that activity worsens pain or tissue injury in the absence of a known lesion. Many of these patients continue to complain of the same degree of pain whether or not they are performing their daily activities. It is clear that prolonged rest is harmful to both body (bone demineralization,47 cardiac deconditioning,48,49 and loss of muscle strength) and mind (depression and anhedonia).50,51 The physician who prescribes to the patients with low back pain has clearly done them no favors.

Similarly to the notion that an individual’s back pain can affect his or her job, the characteristics of the job can affect the back pain. A study by Boos et al. showed that the characteristics of one’s job (listlessness, job satisfaction, working in shifts) were more likely than MRI to identify disc abnormalities and to predict whether one would seek medical treatment.52 Similarly, these factors also are useful in predicting which patients are likely not to be working at follow-up.

All of these issues have opened up much controversy and academic thought to litigation and workers compensation in the current health-care system. In the present system, compensation is largely tied to the presence of physical examination findings and imaging confirmation of disc herniation. Some studies suggest that psychological factors may also be tied in to the selection of patients for workers compensation benefits and that patients with emotional instability may be less likely to receive compensation.53 There is decent evidence to suggest that patients who receive time-limited workers compensation as opposed to long-term disability are more likely to return to work and have a good outcome.54 Another study by Atlas et al. also revealed that patients who were receiving workers compensation at baseline prior to their low back disability were more likely to be receiving long-term disability benefits than those who were not (27% vs. 7%), and they were also slightly less likely to be working at 4-year follow-up.55 This correlates with the earlier assertion that time off work and prolonged compensation benefits allow patients to more easily adopt the sick role.

Summary

We advocate a multidisciplinary approach in the spine clinic that involves spine surgeons, occupational therapists, physical therapists, mental health professionals, sports medicine specialists, and social workers. Using this method, appropriate surgical candidates can be selected, and the remainder of patients can be funneled into a low back training program. This program allows them to become empowered and take control and initiative in their disease and avoids their “shopping” around to other clinics. Only by addressing all of these issues can care for patients with low back pain be adequate and efficient.

Jamison R.N., Matt D.A., Parris W.C. Effects of time-limited vs. unlimited compensation on pain behavior and treatment outcome in low back pain patients. J Psychosom Res. 1988;32:277-283.

Melzack R., Wall P.D. Pain mechanisms: a new theory. Science. 1965;150:971-979.

Volinn E., Turczyn K.M., Loeser J.D. Theories of back pain and health care utilization. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 1991;2:739-748.

Volinn E., Van Koevering D., Loeser J.D. Back sprain in industry. The role of socioeconomic factors in chronicity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1991;16:542-548.

Waddell G., Morris E.W., Di Paola M.P., et al. A concept of illness tested as an improved basis for surgical decisions in low-back disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1986;11:712-719.

Waddell G. Low back disability. A syndrome of Western civilization. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 1991;2:719-738.

Waddell G. The back pain revolution, ed 2. London: Elsevier; 2004.

1. Waddell G. Low back disability. A syndrome of Western civilization. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 1991;2:719-738.

2. Brown T. On irritation of the spinal nerves. Glasgow Med J. 1828;1:131-160.

3. Erichsen J.E. On railway and other injuries of the nervous system: six lectures on certain obscure injuries of the nervous system commonly met with as a result of shock to the body received in collisions in railways. London: Walton & Maberly; 1866.

4. King H.D. Injuries of the back from a medical legal standpoint. Texas State J Med. 1915;11:442-445.

5. Mixter W.J., Barr J.S. Rupture of the intervertebral disc with involvement of the spinal canal. N Engl J Med. 1934;211:210-215.

6. Rubin D.I. Epidemiology and risk factors for spine pain. Neurol Clin. 2007;25:353-371.

7. Papageorgiou A.C., Croft P.R., Thomas E., et al. Influence of previous pain experience on the episode incidence of low back pain: results from the South Manchester Back Pain Study. Pain. 1996;66:181-185.

8. Cassidy J.D., Cote P., Carroll L.J., Kristman V. Incidence and course of low back pain episodes in the general population. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30:2817-2823.

9. Waxman R., Tennant A., Helliwell P. A prospective follow-up study of low back pain in the community. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25:2085-2090.

10. Andersson G.B. Epidemiology of low back pain. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl. 1998;281:28-31.

11. Lawrence R.C., Helmick C.G., Arnett F.C., et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and selected musculoskeletal disorders in the United States. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:778-799.

12. Hestbaek L., Leboeuf-Yde C., Manniche C. Low back pain: what is the long-term course? A review of studies of general patient populations. Eur Spine J. 2003;12:149-165.

13. Walker B.F. The prevalence of low back pain: a systematic review of the literature from 1966 to 1998. J Spinal Disord. 2000;13:205-217.

14. Fullenlove T.M., Williams A.J. Comparative roentgen findings in symptomatic and asymptomatic backs. Radiology. 1957;68:572-574.

15. Horal J. The clinical appearance of low back disorders in the city of Gothenburg, Sweden. Comparisons of incapacitated probands with matched controls. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl. 1969;118:1-109.

16. La Rocca H., Macnab I. Value of pre-employment radiographic assessment of the lumbar spine. Can Med Assoc J. 1969;101:49-54.

17. Splithoff C.A. Lumbosacral junction; roentgenographic comparison of patients with and without backaches. JAMA. 1953;152:1610-1613.

18. Cooper J.K., Kohlmann T. Factors associated with health status of older Americans. Age Ageing. 2001;30:495-501.

19. Bressler H.B., Keyes W.J., Rochon P.A., et al. The prevalence of low back pain in the elderly. A systematic review of the literature. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1999;24:1813-1819.

20. Hartvigsen J., Christensen K., Frederiksen H. Back and neck pain exhibit many common features in old age: a population-based study of 4,486 Danish twins 70-102 years of age. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004;29:576-580.

21. Salminen J.J., Erkintalo M., Laine M., et al. Low back pain in the young. A prospective three-year follow-up study of subjects with and without low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995;20:2101-2107. discussion 2108

22. Fairbank J.C., Pynsent P.B., Van Poortvliet J.A., et al. Influence of anthropometric factors and joint laxity in the incidence of adolescent back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1984;9:461-464.

23. Burton A.K., Clarke R.D., McClune T.D., et al. The natural history of low back pain in adolescents. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996;21:2323-2328.

24. Hildebrandt V.H. A review of epidemiological risk factors on risk factors of low back pain. In: Buckle P., editor. Musculo-skeletal disorders at work. London: Taylor & Francis; 1987:9-16.

25. Goubert L., Crombez G., De Bourdeaudhuij I. Low back pain, disability and back pain myths in a community sample: prevalence and interrelationships. Eur J Pain. 2004;8:385-394.

26. Melzack R. The McGill Pain Questionnaire: major properties and scoring methods. Pain. 1975;1:277-299.

27. Waddell G., Main C.J., Morris E.W., et al. Chronic low-back pain, psychologic distress, and illness behavior. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1984;9:209-213.

28. Lethem J., Slade P.D., Troup J.D., Bentley G. Outline of a fear-avoidance model of exaggerated pain perception—I. Behav Res Ther. 1983;21:401-408.

29. Troup J.D., Foreman T.K., Baxter C.E., Brown D. 1987 Volvo award in clinical sciences. The perception of back pain and the role of psychophysical tests of lifting capacity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1987;12:645-657.

30. Benn R.T., Wood P.H. Pain in the back: an attempt to estimate the size of the problem. Rheumatol Rehabil. 1975;14:121-128.

31. Rowe M.L. Low back pain in industry. A position paper. J Occup Med. 1969;11:161-169.

32. Waddell G. The back pain revolution, ed 2. London: Elsevier; 2004.

33. Melzack R., Wall P.D. Pain mechanisms: a new theory. Science. 1965;150:971-979.

34. Waddell G., Morris E.W., Di Paola M.P., et al. A concept of illness tested as an improved basis for surgical decisions in low-back disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1986;11:712-719.

35. Herron L., Turner J., Weiner P. A comparison of the Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory and the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory as predictors of successful treatment by lumbar laminectomy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1986;203:232-238.

36. Herron L.D., Turner J., Clancy S., Weiner P. The differential utility of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory. A predictor of outcome in lumbar laminectomy for disc herniation versus spinal stenosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1986;11:847-850.

37. Turner J.A., Herron L., Weiner P. Utility of the MMPI Pain Assessment Index in predicting outcome after lumbar surgery. J Clin Psychol. 1986;42:764-769.

38. Wiltse L.L., Rocchio P.D. Preoperative psychological tests as predictors of success of chemonucleolysis in the treatment of the low-back syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1975;57:478-483.

39. Brown T., Nemiah J.C., Barr J.S., Barry H.Jr. Psychologic factors in lowback pain. N Engl J Med. 1954;251:123-128.

40. Flynn R.J., Salomone P.R. Performance of the MMPI in predicting rehabilitation outcome: a discriminant analysis, double cross-validation assessment. Rehabil Lit. 1977;38:12-15.

41. Dzioba R.B., Doxey N.C. A prospective investigation into the orthopaedic and psychologic predictors of outcome of first lumbar surgery following industrial injury. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1984;9:614-623.

42. Oostdam E.M., Duivenvoorden H.J., Pondaag W. Predictive value of some psychological tests on the outcome of surgical intervention in low back pain patients. J Psychosom Res. 1981;25:227-235.

43. Pheasant H.C., Gilbert D., Goldfarb J., Herron L. The MMPI as a predictor of outcome in low-back surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1979;4:78-84.

44. Volinn E., Van Koevering D., Loeser J.D. Back sprain in industry. The role of socioeconomic factors in chronicity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1991;16:542-548.

45. Payne S.M. Targeting utilization review to diagnostic categories. QRB Qual Rev Bull. 1987;13:394-404.

46. Volinn E., Turczyn K.M., Loeser J.D. Theories of back pain and health care utilization. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 1991;2:739-748.

47. Hansson T., Sandstrom J., Roos B., et al. The bone mineral content of the lumbar spine in patients with chronic low-back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1985;10:158-160.

48. Mayer T.G., Gatchel R.J., Kishino N., et al. Objective assessment of spine function following industrial injury. A prospective study with comparison group and one-year follow-up. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1985;10:482-493.

49. Mayer T.G., Gatchel R.J., Kishino N., et al. A prospective short-term study of chronic low back pain patients utilizing novel objective functional measurement. Pain. 1986;25:53-68.

50. McGill C.M. Industrial back problems. A control program. J Occup Med. 1968;10:174-178.

51. Strang J.P. The chronic disability syndrome. In: Aronoff G., editor. Evaluation and treatment of chronic pain. Baltimore, MD: Urban & Schwarzenberg, 1985.

52. Boos N., Semmer N., Elfering A., et al. Natural history of individuals with asymptomatic disc abnormalities in magnetic resonance imaging: predictors of low back pain-related medical consultation and work incapacity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25:1484-1492.

53. Gallagher R.M., Williams R.A., Skelly J., et al. Workers’ compensation and return-to-work in low back pain. Pain. 1995;61:299-307.

54. Jamison R.N., Matt D.A., Parris W.C. Effects of time-limited vs unlimited compensation on pain behavior and treatment outcome in low back pain patients. J Psychosom Res. 1988;32:277-283.

55. Atlas S.J., Chang Y., Kammann E., et al. Long-term disability and return to work among patients who have a herniated lumbar disc: the effect of disability compensation. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 2000;82:4-15.