5

Psychocutaneous Disorders

Introduction

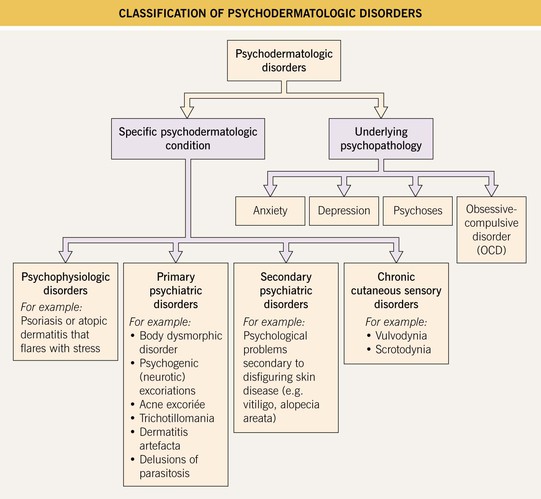

• Psychodermatologic disorders can be classified in two ways: (1) by the specific psychodermatologic condition or (2) by the underlying psychopathology (Fig. 5.1).

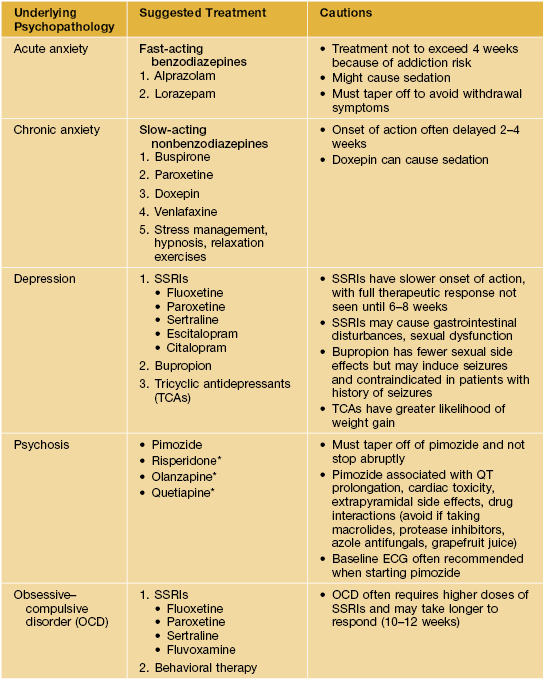

• Treatment is simplified by basing the choice of psychotropic medication or therapy on the underlying psychopathology (Table 5.1).

Table 5.1

Common psychotropic medications used in dermatology.

* Increasing frequency of use because of lower risk of tardive dyskinesia, compared with pimozide.

SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

The More Common Primary Psychiatric Disorders Seen in Dermatology

Body Dysmorphic Disorder

• On a psychiatric spectrum from obsessional to delusional.

• Mean age of onset is 30–35 years; females = males; present in up to 10–15% of dermatologic patients.

• Patients usually concerned with nose, mouth, hair, breasts, or genitalia.

• Consider and assess for this diagnosis in patients seeking multiple cosmetic procedures.

Psychogenic (Neurotic) Excoriations

• A conscious, repetitive, uncontrollable desire to pick, rub, or scratch skin.

• Most common in middle-age; females > males.

• Favors scalp, face, upper back, extensor forearms, shins, buttocks.

• Lesions usually in all stages of evolution: erosions (prurigo simplex), deep circular or linear ulcerations with hypertrophic borders, hypo- or hyperpigmented scars (Fig. 5.2); admixed well-healed scars point to chronicity.

Fig. 5.2 Psychogenic (neurotic) excoriations. Deep, angulated, unnatural-shaped ulceration on the chin. Courtesy, Kalman Watsky, MD.

• DDx: (1) underlying causes of primary pruritus (see Chapter 4); (2) underlying primary cutaneous disorder (e.g., folliculitis).

Acne Excoriée

Trichotillomania

• Defined as hair loss from a patient’s repetitive self-pulling of hair.

• Most helpful to approach the patient by age of onset, in terms of discussing prognosis and treatment.

• Peak onset ages 8–12 years; females > males.

• Most commonly scalp hair, but also eyebrows, eyelashes, or pubic hair.

• Classically see hairs of varying lengths distributed within the area of alopecia; uninvolved areas are normal (Fig. 5.4).

• Sometimes associated ritualistic behavior or trichophagy.

• DDx: other causes of non-scarring alopecia (e.g., alopecia areata, tinea capitis).

Cutting (Self-Injury)

Dermatitis Artefacta

• Rare disorder; majority of patients suffer from borderline personality disorder; may have underlying depression and/or anxiety.

• Onset typically in adolescence or young adulthood; females >> males.

• Lesions often appear in easy-to-reach areas and appear in bizarre shapes and configurations; may employ outside instruments (Fig. 5.5).

Fig. 5.5 Dermatitis artefacta. A ‘Bizarre’ and unnatural appearance of the skin with angulated borders, possibly created with a sharp instrument. B Lesions in multiple stages of evolution, from circular, crusted erosions to ‘bizarre-shaped’ erosions on the mid-shin to hyperpigmented scars. This teenage girl denied knowing how the lesions developed or having any role in the process. C Scars from cigarette burns. D Unusual, linear, hypertrophic scars resulting from self-carving with a sharp instrument. A, Courtesy, John Koo, MD; C, Courtesy, Ronald P. Rapini, MD; D, Courtesy, M. Joyce Rico, MD.

Delusions of Parasitosis

• This delusion is ‘encapsulated’ and other mental functions are usually intact.

• Typical onset is in the mid 50s–60s.

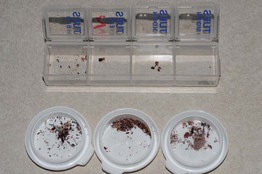

• Patients often bring in bits of skin, lint, and other specimens to prove the existence of the supposed parasites (Fig. 5.6).

Fig. 5.6 Delusions of parasitosis. Samples of alleged ‘parasites’ brought in by a patient (‘matchbox sign’). Courtesy, Kalman Watsky, MD.

• Often experience ‘formication,’ which is a cutaneous sensation of crawling, biting, and/or stinging.

• DDx: (1) legitimate primary dermatologic disorder; (2) true formication without delusion; (3) formication plus delusion, related to substance abuse (e.g., methamphetamines); (4) delusional ideation (i.e., mentally fixated but not completely inflexible).

• Rx: establish rapport with patient first; pimozide or atypical antipsychotics.

For further information see Ch. 7. From Dermatology, Third Edition.