4

Pruritus and Dysesthesia

Pruritus

Etiologies

• May arise secondary to a number of conditions:

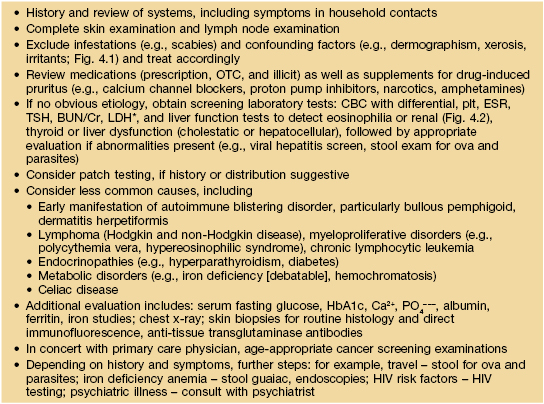

– Dermatologic disorders (Table 4.1).

Table 4.1

Common dermatologic diseases with pruritus as a major symptom.

BP, bullous pemphigoid; DH, dermatitis herpetiformis.

– Allergic or hypersensitivity syndromes.

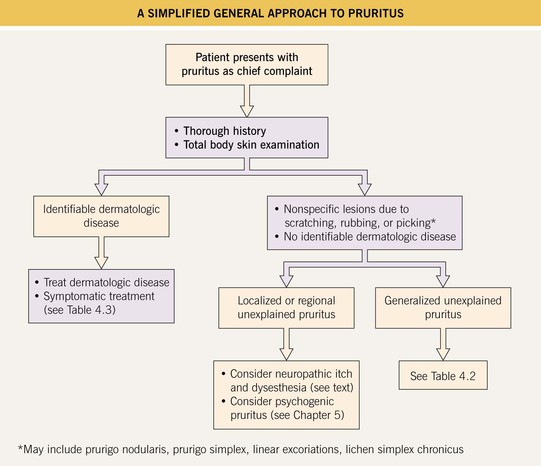

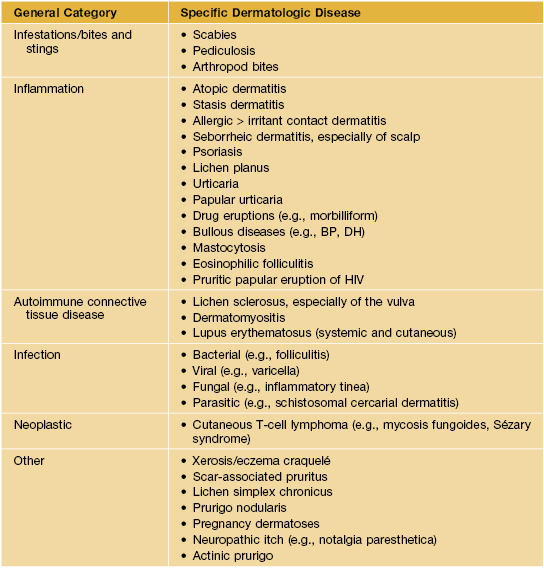

– Systemic diseases (10–25%) and malignancies (Table 4.2; Figs. 4.1 and 4.2).

Table 4.2

Approach to the patient with generalized pruritus and no obvious specific skin disease.

* LDH is often used in a manner similar to an ESR, especially in patients with lymphoma.

BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CBC, complete blood count; Cr, creatinine; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; LDH, lactic dehydrogenase; OTC, over-the-counter; plt, platelets; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone.

Fig. 4.1 Extreme xerosis associated with pruritus in an HIV-infected patient. Courtesy, Elke Weisshaar, MD and Jeffrey D. Bernhard, MD.

Fig. 4.2 Xerosis and pruritus in a patient with chronic renal failure on hemodialysis. There are a few papules of acquired perforating dermatosis admixed with the scratch marks. Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD.

– Toxins associated with kidney or liver dysfunction.

– Neurologic disorders (see text below).

– Psychiatric conditions (see Chapter 5).

• Most patients with pruritus due to an underlying dermatologic disorder present with characteristic or diagnostic skin lesions (e.g., dermatitis of the flexures in atopic dermatitis; see Table 4.1).

• In primary pruritus and secondary pruritus NOT due to an underlying dermatologic disorder, the lesions are usually nonspecific (e.g., linear excoriations [Fig. 4.3], prurigo simplex, prurigo nodularis [Fig. 4.4]).

Fig. 4.3 Linear excoriations on the leg. Although this patient had atopic dermatitis, similar lesions can be seen in patients with ‘primary’ or ‘idiopathic’ pruritus. Courtesy, Elke Weisshaar, MD and Jeffrey D. Bernhard, MD.

Diagnostic Pearls

• Sparing of the mid upper back, an area of patient-hand inaccessibility (‘butterfly sign’) (Fig. 4.5), is suggestive of pruritus NOT associated with a dermatologic disorder; note, however, this sign is not seen in those who use back scratchers or similar devices.

Approach to the Patient with Pruritus

Management of Pruritus

• General treatment measures for pruritus are outlined in Table 4.3.

Table 4.3

Treatment for pruritus/dysesthesia – general measures.

SNRIs, selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors; SSRIs, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; TCAs, tricyclic antidepressants.

Classic Clinical Findings from Chronic Pruritus

Lichen Simplex Chronicus (LSC)

• Skin-colored to pink or hyperpigmented plaques with exaggerated skin lines and a leathery appearance due to repeated, often habitual, scratching or rubbing (Fig. 4.7).

Fig. 4.7 Lichen simplex chronicus of the lateral neck. Note the increased skin markings. Use of topical corticosteroids can lead to a shiny appearance and a rim of hypopigmentation. Courtesy, Elke Weisshaar, MD and Jeffrey D. Bernhard, MD.

• Favors the posterior neck and occipital scalp (Fig. 4.8), anogenital region (Fig. 4.9), and ankles as well as the extensor surface of the forearms and shins.

Fig. 4.8 Lichen simplex chronicus of the posterior neck. The increased skin markings have been likened to the bark of a tree. Courtesy, Ronald P. Rapini, MD.

Fig. 4.9 Lichen simplex chronicus of the scrotum. Secondary pigmentary changes are seen more commonly in darkly pigmented skin. Courtesy, Louis A. Fragola, Jr., MD.

• LSC may be superimposed upon a specific cutaneous disorder, most commonly atopic dermatitis.

• Rx: potent topical CS, often under occlusion (e.g., hydrocolloid dressings), can be helpful.

• Other Rx: intralesional CS or use of an office-applied dressing (e.g., Unna boot) may be required.

Prurigo Nodularis

• Degree of pruritus can vary from moderate to intense.

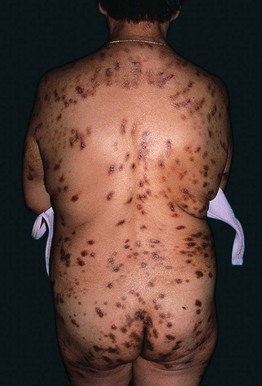

• Lesions usually favor the extensor surfaces of the extremities (see Fig. 4.4), upper back, and buttocks, but they can be widespread in easily reachable areas (Fig. 4.10).

Fig. 4.10 Widespread prurigo nodularis. This patient had underlying atopic dermatitis. Courtesy, Elke Weisshaar, MD and Jeffrey D. Bernhard, MD.

• Rx: depending on the number of lesions, varies from superpotent topical or intralesional CS to phototherapy (UVB [broadband or narrowband] or PUVA) and thalidomide.

• If no underlying reversible disorder is detected (see Table 4.2), prurigo nodularis can be difficult to treat.

Neurologic Etiologies of Pruritus and Dysesthesia

Neuropathic Itch

• CNS-related neuropathic itch syndromes involve abnormalities of the brain.

• Patients with neuropathic itch often present first to a dermatologist.

Trigeminal Trophic Syndrome (TTS)

• Classically involves the nasal ala and typically results from impingement or damage to the sensory portion of the trigeminal nerve (Figs. 4.11 and 4.12).

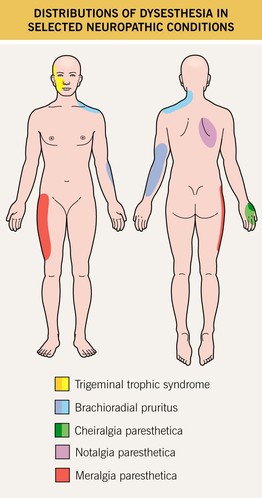

Fig. 4.11 Distributions of dysesthesia in selected neuropathic conditions. Cheiralgia paresthetica is caused by entrapment of the superficial branch of the radial nerve. Darker shades indicate more common areas of involvement. Courtesy, Karynne O. Duncan, MD.

Fig. 4.12 Trigeminal trophic syndrome. Erosions and ulcerations with hemorrhagic crusts favor the ala nasi (A, B). Obvious linear excoriations are seen in the second patient (B). Courtesy, Kalman Watsky, MD.

• Common inciting factors include iatrogenesis (ablation of the Gasserian ganglion to treat intractable trigeminal neuralgia), infection (varicella zoster virus [VZV], herpes simplex virus), stroke (infarction of the posterior cerebellar artery), CNS tumors or their resultant treatment.

Radiculopathies

• The abnormal sensation (e.g., pruritus or other dysesthesia) is perceived in the skin area that is innervated by the damaged SNR(s), and these areas are known as dermatomes (see Fig. 67.10).

• The evaluation of an unexplained radiculopathy should include a neurologic examination.

• If radiologic imaging is negative, electromyogram and nerve conduction studies can be considered.

• Several classic radiculopathies encountered in dermatology are (1) ‘shingles’ or post-herpetic neuralgia (PHN) or post-herpetic itch (PHI); (2) notalgia paresthetica; (3) brachioradial pruritus, and (4) meralgia paresthetica (Fig. 4.11).

Notalgia Paresthetica

• Presents with focal, intense pruritus of the upper back, most commonly along the medial scapular borders (see Fig. 4.11); sometimes the pruritus is accompanied by other dysesthesias (e.g., pain, burning).

• Often, a hyperpigmented patch that is a result of chronic rubbing is seen in the area of pruritus (Fig. 4.13).

Fig. 4.13 Notalgia paresthetica. A circumscribed area of hyperpigmentation on the left mid back (overlying the medial aspect of the scapula) due to chronic rubbing and scratching. The patient complained of significant pruritus in that area. An incidental café au lait macule is on the right mid back. Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD.

• Other Rx: topical anesthetics, gabapentin, and acupuncture.

Brachioradial Pruritus

• Chronic, intermittent pruritus or burning pain of the dorsolateral aspects of the forearms and elbows; sometimes more extensive area of involvement (e.g., shoulder region) (see Fig. 4.11).

• Most patients have photodamaged skin and degenerative cervical spine disease, with UV light exposure and heat serving as triggers.

• The patient can often precisely delineate the affected area with a marking pen, and within this area are excoriations, prurigo simplex lesions, and sometimes even scarring (Fig. 4.14).

Meralgia Paresthetica

Small Fiber Polyneuropathies (SFPN)

• Perhaps the most common cause of chronic pruritus in the following areas: bilateral feet; feet and legs; hands and legs; or other widespread bilateral areas of the body.

• If the diagnosis of SFPN is suspected based on history and neurologic examination, then potentially treatable causes should be identified, including.

– Fasting blood glucose, HbA1c (diabetes mellitus).

– CBC with differential and platelets (hematologic malignancies).

• For SFPN, there are two diagnostic tests:

Dysesthesia Syndromes

Burning Mouth Syndrome (Orodynia)

Burning Scalp Syndrome (Scalp Dysesthesia)

Dysesthetic Anogenital Syndromes

• When all typical secondary causes of anogenital pruritus and dysesthesia have been investigated and treated (e.g., candidiasis, fecal incontinence; see Chapter 60), and the patient still has symptoms, consider lumbosacral radiculopathy (imaging studies), dermographism (trial of oral antihistamines), and contact dermatitis (patch testing).

For further information see Ch. 6. From Dermatology, Third Edition.