CHAPTER 32 Proximal Femoral Osteotomies in Adults for Secondary Osteoarthritis

Femoral Osteotomies for Adult Deformity

Surgical technique

Surgical Technique for Intertrochanteric Osteotomy

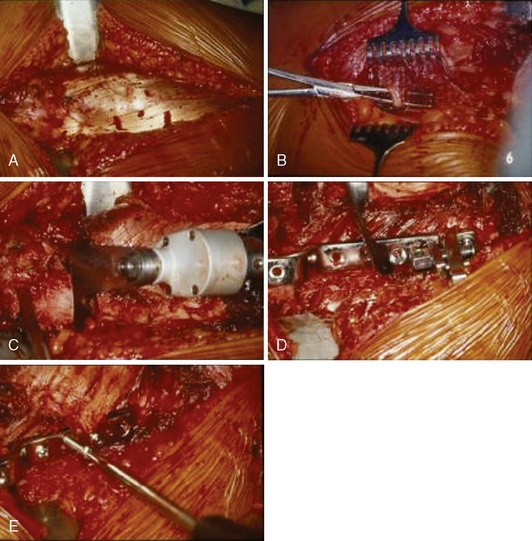

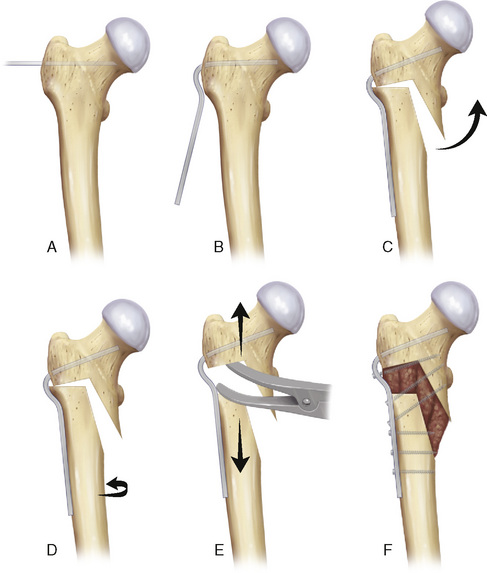

A standard lateral approach is used for all intertrochanteric osteotomies. The vastus lateralis is exposed by incising the fascia lata and reflected with Hohmann retractors to visualize the lateral femur (Figure 32-1, A). The vastus lateralis is sharply removed in the avascular plane from the vastus ridge. The vastus lateralis is detached from the intermuscular septum by blunt dissection, which allows for a wide inspection of the upper femur. Several perforating branches of the profunda femoral artery traverse the vastus lateralis and should be ligated correctly to avoid a postoperative hematoma; care should be taken so that the blunt dissection does not damage these vessels (see Figure 32-1, B). If it is necessary to inspect the hip joint, the approach can be extended proximally (i.e., the Watson-Jones approach), and the joint capsule can be opened to inspect the joint. The joint capsule is not routinely opened but rather only opened when indicated (e.g., for hump resection in a post-SCFE deformity). The linea aspera is decorticated. The seating chisel is inserted in the correct position, and the rotation is marked by placing a K-wire on each side of the planned osteotomy. Before this osteotomy is made, the seating chisel should be pulled back approximately 1 cm. An osteotomy parallel to the seating chisel is then made just proximal to the lesser trochanter (see Figure 32-1, C). Depending on the desired correction, a full or half wedge is removed to allow for the calculated varus–valgus or flexion–extension correction. During the osteotomy, blunt Hohmann retractors are placed around the femur to protect the femoral vessels and the femoral nerve. The definitive fixation is performed under compression with the classic AO (arbeitsgemeinschaft fur osteosynthesefragen) 90-degree or 100-degree blade plate, with different offsets that range from 10 mm to 20 mm. For cases in which extreme valgization is needed (e.g., for the treatment of femoral neck nonunions), a double-angled 120-degree or 130-degree blade plate can be used. For specific cases (e.g., intertrochanteric lengthening), a condylar plate is the preferred option. For all of our intertrochanteric osteotomies that involve the use of more or less right-angled blade plates, we performed the fixation under compression with the use of the AO compression device (see Figure 32-1, D and E). With the use of lateral compression, even open-wedge osteotomies heal without problems.

Potential Pitfalls and Considerations for Intertrochanteric Osteotomy

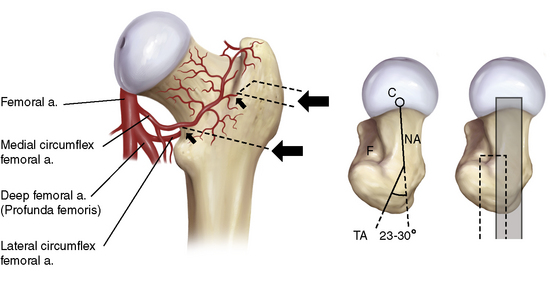

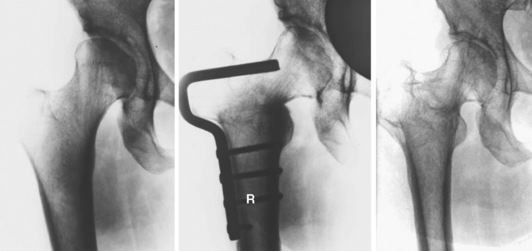

In addition, the placement of the seating chisel or blade plate can cause problems. The occurrence of AVN caused by the osteotomy is a worry. The vascular supply of the femoral head is provided by branches of the dorsal circumflex artery, which can be damaged in the intertrochanteric fossa if the femoral neck is perforated by the seating chisel. This can be avoided with the correct placement of the seating chisel (Figure 32-2).

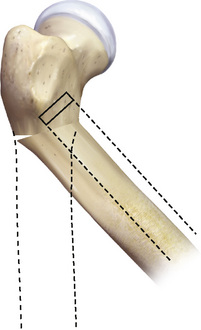

When flexion or extension is added to the osteotomy, the position of the femur after the osteotomy should be anticipated when planning the placement of the blade plate. For example, a seating chisel that is inserted too far anteriorly cannot be fixed properly to the femur after a flexion osteotomy (Figure 32-3).

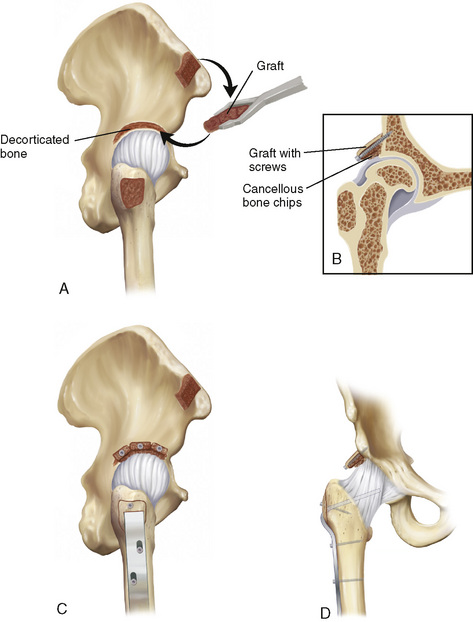

Surgical Technique for Shelf Plasty

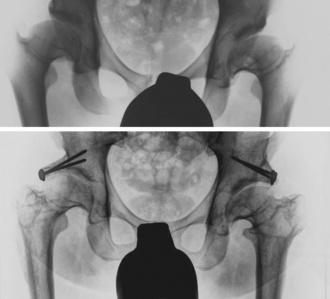

For every procedure, an anterolateral approach was used that was similar to that used with a regular intertrochanteric osteotomy. The gluteal muscles are released with the use of an extracapsular osteotomy of the major trochanter. A cancellous–cortical bone graft is harvested from the ipsilateral interior iliac crest; this graft is bent into two or three blocks and predrilled for screw fixation. The joint capsule remains intact, but it is thinned on the superolateral side until head motion is visible. The supra-acetabular iliac bone is decorticated, and the prepared bone graft is fixated with 3.5-mm or 4.5-mm lag screws, with the patient’s leg in the calculated adduction or abduction position. When the function is tested in adduction, the graft should show plastic deformity. Some cancellous bone is pressed between the thinned joint capsule and the bone graft. A temporary screw fixation of the major trochanter is performed, if necessary, in combination with a distalization procedure (Figure 32-4). We performed distalization when the tip of the major trochanter was positioned higher than the center of rotation of the femoral head after correction. An intertrochanteric osteotomy is then performed in accordance with the standard AO technique; this technique is described earlier in this chapter.

Surgical Technique for Intertrochanteric Lengthening

When an adequate correction is obtained with the use of the previously described technique for an intertrochanteric osteotomy, the blade plate is temporarily held in place by a Verbrugge clamp. A laminar bone spreader is inserted into the osteotomy and opened until the desired lengthening is achieved. The blade plate glides beneath the Verbrugge clamp, thus allowing for lengthening but maintaining the correction. Instead of a laminar bone spreader, it is also possible to use an AO femoral distractor to achieve lengthening. Lengthening up to 3.5 cm can be safely performed without overstretching the nerves. The gap that is created at the intertrochanteric level is filled with corticocancellous bone graft from the iliac crest in combination with cancellous grafts along the decorticated linea aspera. After fixing the blade plate with 4.5-mm cortical screws, one or two of the distal screws are directed cephalad and should be fixated in the proximal fragment, thus creating extra stability (Figure 32-5).

Coxa Valga (Antetorta) and Dysplasia

Deformities such as coxa valga (antetorta) and acetabular dysplasia often coexist. For hips in which the main deformity is on the acetabular side, an acetabulum realigning procedure should be the first choice, and, if necessary, it can be combined with a femoral osteotomy. In these cases, there is a relatively shallow and steep acetabulum that results in a decreased contact surface between the acetabulum and the femoral head (Figure 32-6). Isolated correction of the femoral side cannot solve this problem of containment fully and will fail to eliminate the dislocation force present. Thus, the osteotomy is doomed to fail. However, with some hip deformities, the main deformity lies on the femoral side, with only a mild acetabular dysplasia; the acetabulum might be shallow but not too steep. A varus osteotomy may improve the contact area between the femoral head and the acetabulum in these types of hips and possibly eliminate the dislocating force that is present. Good and long-lasting results may occur. This will not be the case if a fixed subluxation is present, because the weight-bearing surface and the dislocating forces are not altered, thus making the expected results of an intertrochanteric osteotomy poor. The improvement of containment can be judged preoperatively from an abduction correction view. However, currently no objective measurements exist to decide whether an acetabular realigning osteotomy or an intertrochanteric osteotomy is the preferred treatment for specific patients.

Legg-Calvé-Perthes Disease

Osteoarthritic changes develop in adulthood in 50% of patients with these hip deformities. It is most likely that these arthritic changes are caused by an acetabulofemoral incongruency. The origin of this incongruency lies in the fact that the deformed femoral head does not completely fit into the acetabulum. The aim of surgical intervention should be the early correction of this incongruency. The main theory that explains the development of osteoarthritis in these hips is the hinging of the femoral head on the edge of the acetabulum. The best known is the “hinge on abduction,” in which the lateral part of the femoral head hinges on the lateral part of the acetabulum. In these types of hips, a valgus extension osteotomy should be the preferred treatment to eliminate both the causative factor and the contractures that are present by realigning the leg. In hips, after Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, in which the containment of the femoral head is not complete after osteotomy, adding an acetabular shelf plasty can produce excellent results (Figure 32-7). In some cases, valgization alone is not sufficient to restore the function of the abductors as a result of the relatively high position of the major trochanter. In these cases, a simultaneous distalization of the major trochanter is advised.

Results and outcomes

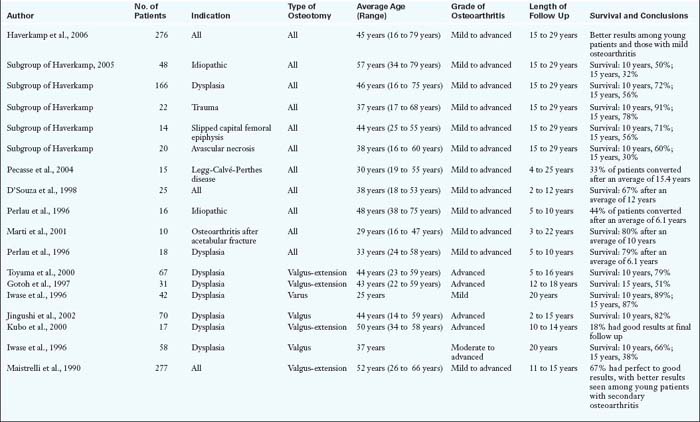

The use of intertrochanteric osteotomies appears to be declining in current clinical practice. It seems that many orthopedic surgeons consider it to be a historic operation that has lost its place for the current treatment of hip disorders. This is probably the result of several retrospective studies that reported poor overall results for intertrochanteric osteotomies. However, these studies also included older patients and hips with advanced osteoarthritis. If the results from these studies are critically screened, certain hip conditions in selected patient groups can be isolated. In these isolated cases, good and long-lasting results were reported. It is important to realize this, because not all patients with osteoarthritis are identical, and it is our goal to identify those patients who could be helped by joint-preserving surgery. These patients generally seem to be younger patients with early secondary osteoarthritis caused by a correctable biomechanical factor (Table 32-1).

Annotated references and suggested readings

D’Souza S.R., Sadiq S., New A.M., Northmore-Ball M.D. Proximal femoral osteotomy as the primary operation for young adults who have osteoarthrosis of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am.. 1998 Oc;80(10):1428-1438.

Eijer H., Myers S.R., Ganz R. Anterior femoroacetabular impingement after femoral neck fractures. J Orthop Trauma.. 2001;15:475-481.

Ganz R., Parvizi J., Beck M., Leunig M., Notzli H., Siebenrock K.A. Femoroacetabular impingement: a cause for osteoarthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res.. 2003;417:112-120.

Girdlestone G.R. Discussion on the late results of operation for chronic painful hip. Proc R Soc Med.. 1926;19(Sect Orthop):48-49.

Gotoh E., Inao S., Okamoto T., Ando M. Valgus-extension osteotomy for advanced osteoarthritis in dysplastic hips. Results at 12 to 18 years. J Bone Joint Surg Br.. 1997 Ju;79(4):609-615.

Haverkamp D., de Jong P.T., Marti R.K. Intertrochanteric osteotomies do not impair long-term outcome of subsequent cemented total hip arthroplasties. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;444:154-160. Mar

Haverkamp D., Eijer H., Patt T.W., Marti R.K. Multidirectional intertrochanteric osteotomy for primary and secondary osteoarthritis—results after 15 to 29 years. Int Orthop.. 2006;30(1):15-20. Feb

Haverkamp D., Marti RK. Intertrochanteric osteotomy combined with acetabular shelfplasty in young patients with severe deformity of the femoral head and secondary osteoarthritis. A long-term follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Br.. 2005;87:25-31.

Iwase T., Hasegawa Y., Kawamoto K., Iwasada S., Yamada K., Iwata H. Twenty years’ followup of intertrochanteric osteotomy for treatment of the dysplastic hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. (331); 1996 Oc:245-255.

Jacobs M.A., Hungerford D.S., Krackow K.A. Intertrochanteric osteotomy for avascular necrosis of the femoral head. J Bone Joint Surg Br.. 1989;71:200-204.

The indication for intertrochanteric osteotomies in AVN is described combined with results..

Jingushi S., Sugioka Y., Noguchi Y., Miura H., Iwamoto Y. Transtrochanteric valgus osteotomy for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the hip secondary to acetabular dysplasia. J Bone Joint Surg Br.. 2002 Ma;84(4):535-539.

Kubo T., Fujioka M., Yamazoe S., Ueshima K., Inoue S., Horii M., Ando K., Imai R., Hirasawa Y. Bombelli’s valgus-extension osteotomy for osteoarthritis due to acetabular dysplasia: results at 10 to 14 years. J Orthop Sci.. 2000;5(5):457-462.

Leunig M., Beck M., Dora C., Ganz R. Femoroacetabular impingement: trigger for the development of osteoarthritis. Orthopade.. 2006;35:77-84.

Maistrelli G.L., Gerundini M., Fusco U., Bombelli R., Bombelli M., Avai A. Valgus-extension osteotomy for osteoarthritis of the hip. Indications and long-term results. J Bone Joint Surg Br.. 1990 Ju;72(4):653-657.

Marti R.K., Chaldecott L.R., Kloen P. Intertrochanteric osteotomy for posttraumatic arthritis after acetabular fractures. J Orthop Trauma.. 2001;15:384-393.

Marti R.K., ten Holder E.J., Kloen P. Lengthening osteotomy at the intertrochanteric level with simultaneous correction of angular deformities. Int Orthop.. 2001;25:355-359.

McMurray T.P. Osteo-arthritis of the hip joint. 1939. Clin Orthop Relat Res.. 1990 De;261:3-10.

Millis M.B., Kim Y.J. Rationale of osteotomy and related procedures for hip preservation: a review. Clin Orthop.. 2002;405:108-121.

Muller M.E. Intertrochanteric osteotomy: indication, preoperative planning, technique. In: Schatzker J., editor. The intertrochanteric osteotomy. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1984:25-66.

Historically the book that everyone performing osteotomies should have read..

Pauwels F. Biomechanics of the normal and diseased hip. Theoretical foundation, technique and results of treatment: an atlas. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1976.

Pecasse G.A., Eijer H., Haverkamp D., Marti R.K. Intertrochanteric osteotomy in young adults for sequelae of Legg-Calve-Perthes’ disease—a long-term follow-up. Int Orthop.. 2004;28:44-47.

Perlau R., Wilson M.G., Poss R. Isolated proximal femoral osteotomy for treatment of residua of congenital dysplasia or idiopathic osteoarthrosis of the hip. Five- to ten-year results. J Bone Joint Surg Am.. 1996 Oc;78(10):1462-1467.

Reigstad A., Grønmark T. Osteoarthritis of the hip treated by intertrochanteric osteotomy. A long-term follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am.. 1984 Ja;66(1):1-6.

Santore R.F., Kantor S.R. Intertrochanteric femoral osteotomies for developmental and posttraumatic conditions. Instr Course Lect.. 2005;54:157-167.

This instructional course lecture gives a good summary of the current knowledge..

Sugioka Y. Transtrochanteric anterior rotational osteotomy of the femoral head in the treatment of osteonecrosis affecting the hip: a new osteotomy operation. Clin Orthop Relat Res.. 1978 Jan-Fe;130:191-201.

Toyama H., Endo N., Sofue M., Dohmae Y., Takahashi H.E. Relief from pain after Bombelli’s valgus-extension osteotomy, and effectiveness of the combined shelf operation. J Orthop Sci.. 2000;5(2):114-123.

Turgeon T.R., Phillips W., Kantor S.R., Santor R.F. The role of acetabular and femoral osteotomies in reconstructive surgery of the hip: 2005 and beyond. Clin Orthop Relat Res.. 2005;441:188-199.

Voss C. Coxarthrosis; the temporary hanging hip, a new procedure for operative treatment of painful hip in the aged and other chronic deforming diseases of the hip. Munch Med Wochenschr.. 1956 Jul 13;98(28):954-956.

Watson-Jones R., Robinson W.C. Arthrodesis of the osteoarthritic hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br.. 1956 Fe;38-B(1):353-377.