CHAPTER 17 Procedures for Benign Anorectal Disease

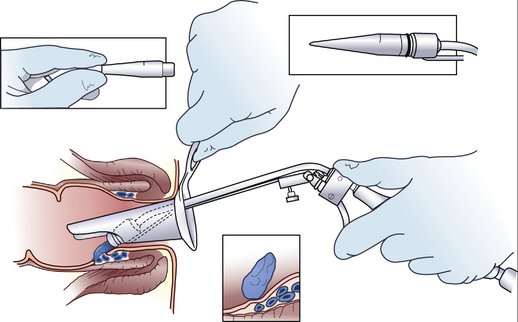

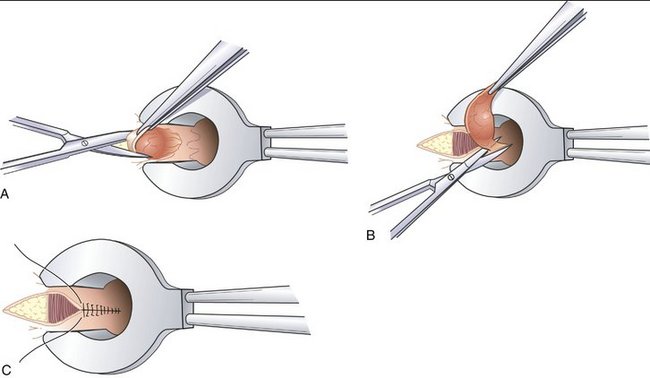

HEMORRHOIDS

INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION

COMPONENTS OF THE PROCEDURE AND APPLIED ANATOMY

COMPLICATIONS

ANORECTAL ABSCESS

BACKGROUND

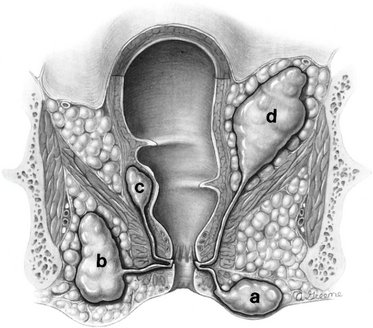

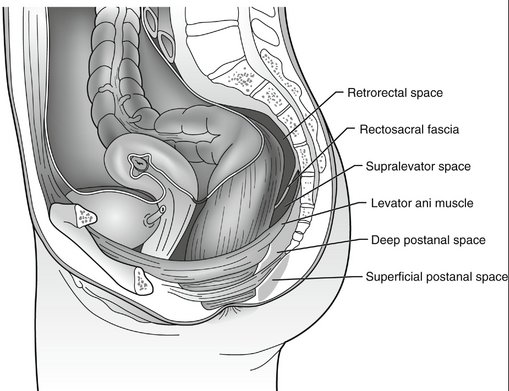

The majority of anorectal abscesses result from infection originating in the anal crypts located at the dentate line. Abscesses are classified as perianal (60%), ischiorectal (20%), intersphincteric (10%), or supralevator (9%), depending on their location (Fig. 17-4). Deep postanal space abscesses represent a particular challenge. The deep postanal space is protected from view by the sacrum, and abscesses originating in this cavity may track circumferentially into the ischiorectal, intersphincteric, or supralevator space before they are diagnosed (Fig. 17-5). This pattern of spread results in what is known as a horseshoe abscess.

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION

COMPONENTS OF THE PROCEDURE AND APPLIED ANATOMY

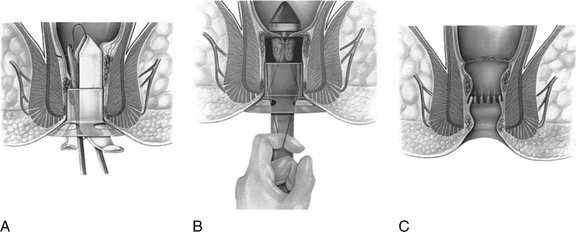

ANORECTAL FISTULAE

BACKGROUND

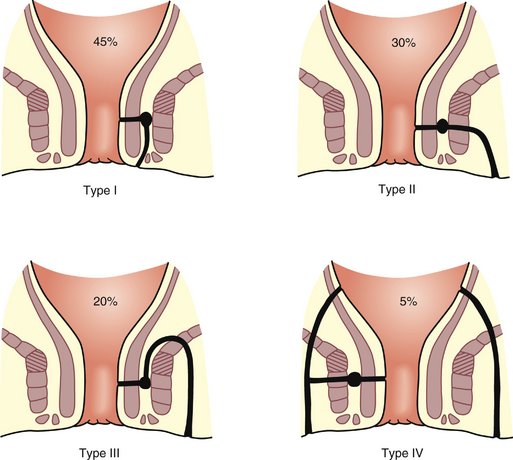

A fistula is defined as the abnormal communication between two epithelial-lined surfaces. Most anorectal fistulae begin as abscesses of the anal crypts. The offending organisms are almost always enteric bacteria. A communication between the epithelial surface of the perianal region and the infected anal crypt may form spontaneously or iatrogenically after surgical drainage. Anorectal fistulae are classified by the anatomic relationship of the tract to the anal sphincters as intersphincteric, trans-sphincteric, suprasphincteric, or extrasphincteric (Fig. 17-6).

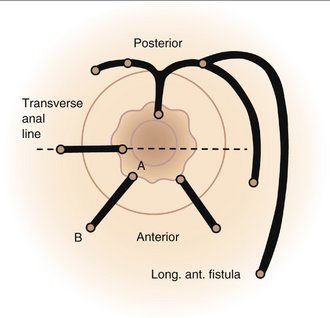

The path of fistulae generally follows Goodsall’s rule (Fig. 17-7), which states that posterior external openings communicate with the anal canal at the posterior midline through a curved tract, whereas anterior external openings communicate directly with the closest anal crypt along a straight path. Multiple anterior external openings typically have separate internal openings. Multiple posterior external openings usually have a common posterior midline internal opening.

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION

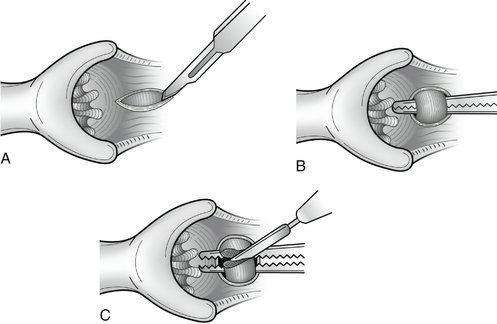

COMPONENTS OF THE PROCEDURE AND APPLIED ANATOMY

FISSURE IN ANO

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION

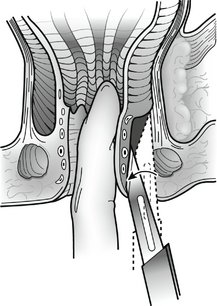

COMPONENTS OF THE PROCEDURE AND APPLIED ANATOMY

Cameron JL. Current Surgical Therapy, 8th ed. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2004.

Kleighley MRB. Anorectal disorders. In: Fischer JE, Bland KI, editors. Mastery of Surgery. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007:1609-1627.

Nelson H. Anus. In: Townsend CM, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL, editors. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery: The Biological Basis of Modern Surgical Practice. 17th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004:1483-1512.