CHAPTER 58 Principles of vitreoretinal surgery

Techniques and technologies

Robert Machemer, the inventor of pars plana vitrectomy, wrote his seminal monograph in 19751, having done more than 500 vitrectomies at that time: ‘Pars plana vitrectomy is not an easy type of surgery. Some formal or informal training with an experienced vitreous surgeon is highly recommended.’ Bearing this in mind, it is clear that this chapter cannot teach vitreoretinal surgeons in practical terms. It should help, however, to deliver a basis to understand the principle techniques of current vitreoretinal surgery. This might be of advice in numerous clinical situations occurring during vitreoretinal surgery – a procedure simply called ‘vitrectomy’.

History and concept of vitreoretinal surgery

Fifteen years after his first publication on vitreous removal in a closed system, Machemer wrote, ‘the next step was treatment of the retina itself. It takes an unconventional mind to break major taboos …2.’ It was Machemer himself who previously broke with the greatest taboo. When he left Germany to join the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, vitreous removal was thought of subsequently resulting in phthisis. In Miami, Machemer came across Kasner whose revolutionary clinical work of the 1960s has proved that an eye can also function without the vitreous3. Machemer and Parel developed the vitreous infusion suction cutter (VISC), a 17-gauge instrument which combined suction, cutting, infusion, and illumination properties in one handpiece4. For the first time, it was possible to remove vitreous hemorrhage obscuring the optical axis, which otherwise had to be left untreated5,6. The VISC, however, required a 2.7 mm sclerotomy, and the turbulence the infusion caused at the tip of the vitrectomy port made selective removal of the vitreous difficult. O’Malley and Heintz separated the infusion line from the vitrectomy probe and opened a third sclerotomy for additional instruments, thereby creating the 20-gauge three-port approach which still serves as a standard for vitrectomy almost 40 years later7. At the same time, and in collaboration with Oertli instruments (Berneck, Switzerland), Klöti in Zürich developed the ‘Klöti’-stripper for vitreous removal, which is still in daily use in many vitreoretinal services over the world8,9.

The new and spectacular technique of vitrectomy seemed to offer the solution for all problems in the vitreous cavity2. Not only was the optical axis cleared of vitreous opacities, but also the retina itself could now be approached. Epiretinal membranes were removed, and traction was released from the retina10. In the mid-1970s, however, it gradually became more obvious that the expectations pinned on vitrectomy especially regarding the treatment of complicated forms of retinal detachment could not be fulfilled. At the same time, Scott in Cambridge used silicone oil as a tamponade of otherwise untreatable retinal breaks, a technique initially introduced by Cibis11–14. As a logical consequence of development, also knowing Machemer’s approach, Haut in Paris combined both techniques, i.e. vitrectomy and silicone oil as an internal tamponade, and the combination of vitreous removal with traction release and silicone oil tamponade has become the method of choice in the treatment of complicated forms of retinal detachment2,15.

Fundamental principles, indications, and goals of surgery

Vitreous removal is the main goal of vitrectomy. It clears the optical axis and provides access to the retina. Vitreoretinal traction is released by vitreous removal which therefore should be as complete as possible. Vitreoretinal pathology such as epiretinal membranes can then be approached and removed. Subretinal fluid can be drained via the retinal tear if present or through a drainage retinotomy. Endolaser photocoagulation can be applied, and an appropriate tamponade is filled into the vitreous cavity at the end of the procedure. Indications for vitrectomy are summarized in Box 58.1.

Surgical approach

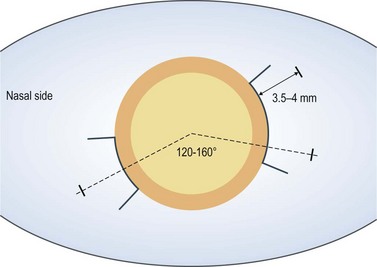

For 20-gauge vitrectomy, a conjunctival incision is performed at the limbus both nasally and temporally (Fig. 58.1). Episcleral vessels are cauterized. A microvitreoretinal (MVR) blade is kept perpendicular to the sclera at 3.5–4 mm distance from the limbus as mentioned above. Care is taken to aim toward the midvitreous cavity to reduce the risk of hitting the lens or damaging the retina. The infusion cannula is typically placed inferotemorally. Therefore, a 7-0 Vicryl suture on a spatulated needle is placed in a mattress fashion at the sclerotomy site. A slip knot is tied and holds the infusion line in place. At the end of vitrectomy, the slip knot is loosened and the same mattress suture is used to close the sclerotomy.

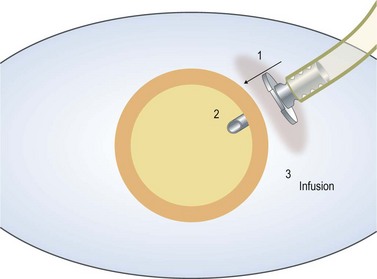

Care should be taken to ensure that the infusion line enters the vitreous cavity, and not the suprachoroidal space. The infusion cannula must be visualized through the dilated pupil by rotating the eye away from the surgeon while the infusion line is grasped and gently pushed toward the central vitreous cavity. Once the position of the infusion cannula has been confirmed, the infusion is turned on (Fig. 58.2).

Fundamental principles of vitreous removal

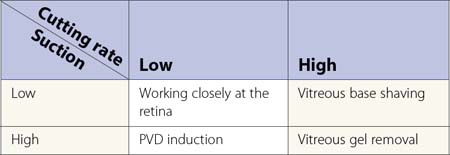

Steve Charles developed an engineering approach to vitreoretinal surgery16. It is highly recommended to read his articles to get an understanding of some fundamental principles regarding the engineering aspects of vitreoretinal surgery. It is noteworthy, however, that in previous years one had to choose between high cutting rates associated with lower flow rates, and low cutting rates allowing high aspiration volume. Recent developments in pump systems and improved cutter design have made surgery more effective for the surgeon and safer for patient.

In my personal experience, three principles are of utmost importance:

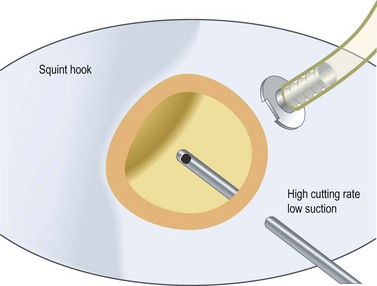

Induction of posterior vitreous detachment

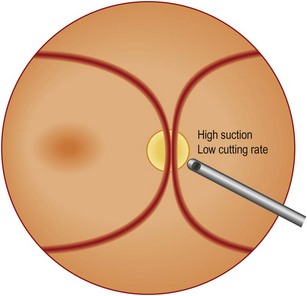

Surgery of the vitreoretinal interface

Internal limiting membrane (ILM) peeling

There has been some debate on the use of dyes for better visualization of the ILM. There is no doubt that, given a special dye is definitely non-toxic, it helps a lot in removing the ILM completely. However, care should be taken to use any dye available as this may cause permanent functional impairment, and any attempt should be made to minimize both illuminance and surgical time spent at the macula17,18.

Reattachment of the retina

Perfluorocarbon liquids (PFCLs) are fluorinated synthetic liquids containing carbon–fluoride bonds. With specific gravities around 2, PFCLs are denser than water, allowing hydrokinetic manipulation of the retina19. They are immiscible with water and are optically clear. The surface tension of PFCLs in water is high, providing an effective tamponading effect and preventing the liquid from passing through a retinal tear into the subretinal space, given no residual traction is present at the retina. Assisted by gravity, the PFCLs fill the vitreous cavity in a posterior-to-anterior fashion, tamponading the retina against the retinal pigment epithelium. This forces the subretinal fluid to pass through the peripheral tear into the vitreous cavity.

There are several important issues to remember when PFCLs are employed:

Retinotomy and retinectomy

Relaxing retinotomy is primarily a procedure of last resort when the retina fails to relax sufficiently to permit reattachment, even after apparently complete removal of the vitreous and all epiretinal and subretinal membranes. Retinotomy (incising the retina) and retinectomy (excising the retina) are indicated only when retinal contraction cannot be relieved adequately by membrane dissection20,21. The main indications for retinotomy are PVR, proliferative diabetic retinopathy, giant retinal tears, and retinal incarceration due to penetrating trauma or surgically induced by previous vitrectomy at the sclerotomy site.

Choice of tamponade

In case of air and longer-acting gas such as sulfur hexafluoride (SF6), perfluoroethan (C2F6), and perfluoropropane (C3F8), the high surface tension between the gas bubble and fluid prevents vitreous fluid from entering a retinal break22. This allows the retinal pigment epithelium to absorb the subretinal fluid, reattaching the retina23. All these gases are inert in the vitreous cavity, but the longer-acting gases in their pure form will expand as dissolved air from the bloodstream will enter the gas-filled vitreous cavity to equilibrate more rapidly than the gas can be absorbed24. As a consequence, and because of the relatively inelastic sclera, the intraocular pressure will increase. If a complete filling of the vitreous cavity is wanted at the end of vitrectomy, a non-expanding mixture of gas has to be chosen to avoid a marked pressure rise (Table 58.2).

Ultimately, however, each gas is absorbed into the bloodstream, at various time intervals. Absorption of an intraocular gas bubble is approximated by a first-order exponential decay equation. This means that the bubble volume decreases by 50% for each half-life25.

Silicone oil

Unlike other vitreous substitutes, silicone oil may remain in the eye almost permanently. Silicone oil is a term used for a group of clear inert hydrophobic polymer compounds based on siloxane chemistry26. The viscosity is determined by the lengths of the polymer, ranging from 1000 to 12 500 cSt. Silicone oil has a density of 0.975 – less than that of water – and thus floats on vitreous fluid. Its refractive index is 1.4035, which is slightly higher than that of the vitreous (1.33). The interfacial tension of silicone oil is high (40 dyn/cm2), but less than that of the interface between gas and water (70 dyn/cm2).

The complications of the use of silicone oil are mainly related to its migration into the anterior chamber. This may especially occur in pseudophakic patients with zonulolysis and in aphakic eyes, and cause keratopathy if left untreated. Aphakic eyes need an inferior peripheral iridectomy to enable the aqueous to pass from the posterior chamber to the anterior chamber when the silicone oil occludes the pupil27. Aphakic patients should be advised not to stay in supine position to avoid the oil entering the anterior chamber.

Current developments

Over the last several years, there has been a major shift in how vitreoretinal surgery is performed. In 2002, 25-gauge vitrectomy was introduced, and in 2003, Eckardt promoted 23-gauge vitrectomy28,29. Both approaches allow for transconjunctival sutureless vitrectomy, associated with increased patient comfort and reduced operating times. While early 25 g instrumentation was limited by excessive flexibility, subsequent generations became more rigid. However, when instruments comparable to 20 g systems are needed, 23 g systems clearly show advantages compared with 25 g, facilitating manipulation of the eye during surgery and shaving of the peripheral vitreous gel.

The most recent achievement in vitreoretinal surgery is the combination of pharmacology and vitrectomy, or even replacing vitrectomy by an intravitreal injection30. Mainly plasmin and microplasmin (ocriplasmin) have shown their potential to create PVD and to liquefy the vitreous gel31. Several clinical studies were undertaken to investigate the concept of pharmacology-assisted vitrectomy32. These studies show that a reasonable number of macular hole patients won’t need vitrectomy any more, as vitreofoveal adhesion can be cleared by a simple intravitreal injection, with subsequent macular hole closure. It remains to be defined in the future which patients are eligible for this type of treatment, and which will still need vitrectomy.

Drug delivery systems will also change our current treatment modalities. Given their minimally invasive nature, vitreoretinal diseases may be treated earlier before advanced stages of disease have developed. This is of special importance in diabetic retinopathy and in proliferative vitreoretinopathy where visual function remains limited, despite anatomical success. Induction of PVD at an early disease stage may prevent further deterioration by relieving traction and by enhancing vitreous oxygen levels, and neuroprotective agents may hold the promise of maintaining or even improving visual function when mechanical manipulation of the retina has reached its limit33. The next step in vitrectomy is improving retinal function by introducing pharmacological means.

1 Machemer R. Vitrectomy, a pars plana approach. New York, San Francisco, London: Grune & Stratton; 1975.

2 Zivojnovic R. Silicone Oil in Vitreoretinal Surgery. Dordrecht: Martinus Nijhoff/Dr W. Junk Publishers; 1987.

3 Kasner D, Miller GR, Taylor WH, et al. Surgical treatment of amyloidosis of the vitreous. Trans Am Acad Ophthslmol Otolaryngol. 1968;72(3):410-418.

4 Machemer R, Parel JM, Buettner H. A new concept for vitreous surgery. I. Instrumentation. Am J Ophthalmol. 1972;73(1):1-7.

5 Machemer R, Norton EW. Vitrectomy, a pars plana approach. II. Clinical experience. 1972;10:178-185.

6 Machemer R, Norton EW. A new concept for vitreous surgery. Indications and results. 1972;74(6):1034-1056.

7 O’Malley C, Heintz RM. Vitrectomy via the pars plana: a new instrumentation system. Trans Pac Coast Otoophthalmol Soc Annu Meet. 1972;53:121-137.

8 Klöti R. [Vitrectomy. I. A new instrument for posterior vitrectomy]. Albrecht Von Graefes Arch Klin Exp Ophthalmol. 1973;187(2):161-170.

9 Klöti R. [Vitrectomy. II. Surgical technique with the vitreous stripper (author’s transl)]. Albrecht Von Graefes Arch Klin Exp Ophthalmol. 1973;189(2):125-135.

10 Kampik A, Kenyon KR, Michels RG, et al. Epiretinal and vitreous membranes. Comparative study of 56 cases. Arch Ophthalmol. 1981;99(8):1445-1454.

11 Cibis PA, Becker B, Okun E, et al. The use of liquid silicone in retinal detachment surgery. Arch Ophthalmol. 1962;68:590-599.

12 Cibis PA. Symposium: Present Status of Retinal Detachment Surgery. Vitreous Transfer and Silicone Injections. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1964;68:983-987.

13 Armaly MF. Ocular tolerance to silicones. I. Replacement of aqueous and vitreous by silicone fluids. Arch Ophthalmol. 1962;68:390-395.

14 Scott JD. The treatment of massive vitreous retraction by the separation of pre-retinal membranes using liquid silicone. Mod Probl Ophthalmol. 1975;15:185-190.

15 Haut J, Ullern M, Boulard ML, et al. [Use of intraocular silicone after vitrectomy as treatment of massive retractions of the vitreous body (preliminary note)]. Bull Soc Ophtalmol Fr. 1978;78(4–5):361-365.

16 Charles S. An engineering approach to vitreoretinal surgery. Retina. 2004;24(3):435-444.

17 Gandorfer A, Haritoglou C, Kampik A. Toxicity of indocyanine green in vitreoretinal surgery. Dev Ophthalmol. 2008;42:69-81.

18 Charles S. Illumination and phototoxicity issues in vitreoretinal surgery. Retina. 2008;28(1):1-4.

19 Chang S. Low viscosity liquid fluorochemicals in vitreous surgery. Am J Ophthalmol. 1987;103(1):38-43.

20 Machemer R. Retinotomy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1981;92(6):768-774.

21 Machemer R, McCuen BW2nd, de Juan EJr. Relaxing retinotomies and retinectomies. Am J Ophthalmol. 1986;102(1):7-12.

22 Norton EW. Intraocular gas in the management of selected retinal detachments. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1973;77(2):OP85-OP98.

23 Lincoff H, Mardirossian J, Lincoff A, et al. Intravitreal longevity of three perfluorocarbon gases. Arch Ophthalmol. 1980;98(9):1610-1611.

24 Chang S, Lincoff HA, Coleman DJ, et al. Perfluorocarbon gases in vitreous surgery. Ophthalmology. 1985;92(5):651-656.

25 Thompson JT. Kinetics of intraocular gases. Disappearance of air, sulfur hexafluoride, and perfluoropropane after pars plana vitrectomy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1989;107(5):687-691.

26 Gabel VP, Kampik A, Burkhardt J. Analysis of intraocularly applied silicone oils of various origins. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1987;225(3):160-162.

27 Ando F. Intraocular hypertension resulting from pupillary block by silicone oil. Am J Ophthalmol. 1985;99(1):87-88.

28 Au Eong KG, Fujii GY, de JEJr, et al. A new three-port cannular system for closed pars plana vitrectomy. Retina. 2002;22(1):130-132.

29 Eckardt C. Transconjunctival sutureless 23-gauge vitrectomy. Retina. 2005;25(2):208-211.

30 Gandorfer A. Objective of pharmacologic vitreolysis. Dev Ophthalmol. 2009;44:1-6.

31 Gandorfer A. Microplasmin-assisted vitrectomy. Dev Ophthalmol. 2009;44:26-30.

32 de Smet MD, Gandorfer A, Stalmans P, et al. Microplasmin intravitreal administration in patients with vitreomacular traction scheduled for vitrectomy: The MIVI I Trial. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(7):1349-1355.

33 Gandorfer A. [The need for pharmacology in vitreoretinal surgery SOE Lecture 2007]. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd. 2007;224(12):900-904.