Principles of Practice

SECTION 1 PRINCIPLES OF PRACTICE

SECTION 2 ETHICS AND THE BUSINESS OF ORTHOPAEDICS

III. Referrals and Ownership of Medical Services

IV. Relationship with Industry

section 1 Principles of Practice

A Orthopaedic practice involves managing relationships among the following:

1. Medical ethics of patient care

2. Business realities of medical practice

3. Legal environment that involves complex and changing laws

B Conflicts of interest among ethical medical care, business goals, and legal considerations can arise. Wherever a conflict of interest arises, it must be resolved in the best interest of the patient.

C The physician-patient relationship is the central focus of all ethical concerns.

D Documents have been developed by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) with the help of other organizations to outline ethical principles of medicine and orthopaedic surgery (http://www.aaos.org/about/papers/ethics.asp):

1. Medical Professionalism in the New Millennium: A Physician Charter (2002)

2. Principles of Medical Ethics and Professionalism in Orthopaedic Surgery (2002)

3. AAOS Standards of Professionalism (http://www3.aaos.org/member/profcomp/sop.cfm)

4. Guide to Professionalism and Ethics in the Practice of Orthopaedic Surgery (2011)

5. Code of Ethics and Professionalism for Orthopaedic Surgeons (2009)

E Most documents are aspirational.

F AAOS Standards of Professionalism are unique in that they represent the minimal level of acceptable conduct.

G Nonadherence to these principles can result in the loss of membership.

II PRINCIPLES OF ETHICS AND PROFESSIONALISM

A Ethics is the discipline dealing with the principles or moral values that govern relationships between and among individuals and defines what the orthopaedic surgeon ought to do.

B Key elements of the AAOS Code of Ethics and Professionalism for Orthopaedic Surgeons (2009):

1. The physician-patient relationship is the “central focus of all ethical concerns.”

2. Conduct of the orthopaedic surgeon must have the following goals:

Emphasize the patient’s best interests

Emphasize the patient’s best interests

Provide “competent and compassionate care”

Provide “competent and compassionate care”

Obey the law and maintain professional dignity and discipline

Obey the law and maintain professional dignity and discipline

3. Conflicts of interest are common

They must be resolved in the best interest of the patient.

They must be resolved in the best interest of the patient.

Relationships with industry and ownership of medical facilities are the most common areas of conflict and are best managed with full disclosure.

Relationships with industry and ownership of medical facilities are the most common areas of conflict and are best managed with full disclosure.

4. The other sections of the code address additional important issues.

C Medical Professionalism in the New Millennium: A Physician Charter (2002)

1. The AAOS adopted the charter crafted by physicians throughout the industrialized world who were concerned about changes in health care delivery systems that threaten the values of professionalism.

Three fundamental principles of professionalism define the basis of the contract between the field of medicine and society:

Three fundamental principles of professionalism define the basis of the contract between the field of medicine and society:

2. The charter also defines a set of 10 professional responsibilities that apply to physicians.

Professional competence: Individual commitment and the profession must strive to ensure that its members are competent.

Professional competence: Individual commitment and the profession must strive to ensure that its members are competent.

Honesty with patients: Good information must be provided before and after treatment, especially with unanticipated outcomes.

Honesty with patients: Good information must be provided before and after treatment, especially with unanticipated outcomes.

Patient confidentiality: Privacy reinforces trust in the profession, but it may have to be disregarded if the patient endangers other people.

Patient confidentiality: Privacy reinforces trust in the profession, but it may have to be disregarded if the patient endangers other people.

Appropriate relations: Patients must never be exploited for sexual or financial advantage.

Appropriate relations: Patients must never be exploited for sexual or financial advantage.

Improving the quality of care: Physicians must maintain knowledge, reduce errors, and create mechanisms to improve care.

Improving the quality of care: Physicians must maintain knowledge, reduce errors, and create mechanisms to improve care.

Improving access to care: Physicians should reduce barriers to access that are based on laws, education, and finances.

Improving access to care: Physicians should reduce barriers to access that are based on laws, education, and finances.

Just distribution of finite resources: Physicians should promote the wise and cost effective use of limited resources.

Just distribution of finite resources: Physicians should promote the wise and cost effective use of limited resources.

Scientific knowledge: Physicians should promote research and create new knowledge and use it appropriately.

Scientific knowledge: Physicians should promote research and create new knowledge and use it appropriately.

Managing conflicts of interest: Physicians must recognize and disclose to patients and to public when reporting results of clinical trials or guidelines.

Managing conflicts of interest: Physicians must recognize and disclose to patients and to public when reporting results of clinical trials or guidelines.

Professional responsibilities: Physicians must work collaboratively and participate in self-regulating and self-disciplining other members of profession.

Professional responsibilities: Physicians must work collaboratively and participate in self-regulating and self-disciplining other members of profession.

D Standards of professionalism represent the mandatory minimum levels of acceptable conduct for orthopaedic surgeons (http://www3.aaos.org/member/profcomp/sop.cfm).

1. Providing musculoskeletal services to patients (2008):

Responsibility to the patient is paramount.

Responsibility to the patient is paramount.

Provide equal treatment of patients regardless of race, color, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, religion, or national origin.

Provide equal treatment of patients regardless of race, color, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, religion, or national origin.

Provide needed and appropriate care or refer to a qualified alternative provider.

Provide needed and appropriate care or refer to a qualified alternative provider.

Present pertinent medical facts and obtain informed consent.

Present pertinent medical facts and obtain informed consent.

Advocate for the patient and provide the most appropriate care.

Advocate for the patient and provide the most appropriate care.

Safeguard patient confidentiality and privacy.

Safeguard patient confidentiality and privacy.

Maintain appropriate relations with patients.

Maintain appropriate relations with patients.

Respect a patient’s request for additional opinions.

Respect a patient’s request for additional opinions.

Pursue lifelong scientific and medical learning.

Pursue lifelong scientific and medical learning.

Provide services and use techniques only for which he or she is qualified by personal education, training, or experience.

Provide services and use techniques only for which he or she is qualified by personal education, training, or experience.

If impaired by substance abuse, seek professional care and limit or cease practice as directed.

If impaired by substance abuse, seek professional care and limit or cease practice as directed.

If impaired by mental or physical disability, seek professional care and limit or cease practice as directed.

If impaired by mental or physical disability, seek professional care and limit or cease practice as directed.

Disclose to the patient any conflict of interest, financial or otherwise, that may influence care.

Disclose to the patient any conflict of interest, financial or otherwise, that may influence care.

Do not enter into a relationship in which the surgeon pays for the right to care for patients with musculoskeletal disorders.

Do not enter into a relationship in which the surgeon pays for the right to care for patients with musculoskeletal disorders.

Make a reasonable effort to ensure that the academic institution, hospital, or employer does not pay for the right to care for patients.

Make a reasonable effort to ensure that the academic institution, hospital, or employer does not pay for the right to care for patients.

Do not couple a marketing agreement or provision services, supplies, equipment, or personnel with required patient referrals.

Do not couple a marketing agreement or provision services, supplies, equipment, or personnel with required patient referrals.

2. Professional relationships (2005)

Responsibility to the patient is paramount.

Responsibility to the patient is paramount.

Maintain fairness, respect, and confidentiality with colleagues and other professionals.

Maintain fairness, respect, and confidentiality with colleagues and other professionals.

Act in a professional manner with colleagues and other professionals.

Act in a professional manner with colleagues and other professionals.

Work collaboratively to reduce medical errors, increase patient safety, and improve outcomes.

Work collaboratively to reduce medical errors, increase patient safety, and improve outcomes.

3. Orthopaedic expert witness testimony (2010)

Provide fair and impartial opinions.

Provide fair and impartial opinions.

Evaluate care by standards of time, place, and context as delivered.

Evaluate care by standards of time, place, and context as delivered.

Do not condemn standard care or condone substandard care.

Do not condemn standard care or condone substandard care.

Explain the basis for any opinion that varies from standard.

Explain the basis for any opinion that varies from standard.

Seek and review all pertinent records.

Seek and review all pertinent records.

Have knowledge and experience, and respond accurately to questions.

Have knowledge and experience, and respond accurately to questions.

Have current valid, unrestricted license to practice medicine.

Have current valid, unrestricted license to practice medicine.

Have current board certification in orthopaedic surgery (i.e., American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery).

Have current board certification in orthopaedic surgery (i.e., American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery).

Have an active practice or familiarity with current practices to warrant expert designation.

Have an active practice or familiarity with current practices to warrant expert designation.

Accurately represent credentials, qualifications, experience, or background.

Accurately represent credentials, qualifications, experience, or background.

Fees should not be contingent on outcome.

Fees should not be contingent on outcome.

Expect reasonable compensation that is based on expertise, time, and effort needed to address issue.

Expect reasonable compensation that is based on expertise, time, and effort needed to address issue.

4. Research and academic responsibilities (2006)

Responsibility to patient is paramount.

Responsibility to patient is paramount.

Seek peer review, and follow regulations.

Seek peer review, and follow regulations.

Be truthful with patients and colleagues.

Be truthful with patients and colleagues.

Report fraudulent or deceptive research.

Report fraudulent or deceptive research.

Claim credit only if substantial contributions made.

Claim credit only if substantial contributions made.

Give credit when presenting other’s ideas, language, data, graphics, or scientific protocols.

Give credit when presenting other’s ideas, language, data, graphics, or scientific protocols.

Make significant contributions when publishing manuscripts.

Make significant contributions when publishing manuscripts.

Disclose existence of duplicate publications.

Disclose existence of duplicate publications.

Include and credit or acknowledge all substantial contributors.

Include and credit or acknowledge all substantial contributors.

5. Advertising by Orthopaedic Surgeons (2007)

Advertising must not suggest any of the following:

Advertising must not suggest any of the following:

Do not use false or misleading statements.

Do not use false or misleading statements.

Use no misleading representation about ability to provide medical treatment.

Use no misleading representation about ability to provide medical treatment.

Use no false or misleading images or photographs.

Use no false or misleading images or photographs.

Use no misrepresentations that communicate a false degree of relief, safety, effectiveness, or benefits of treatment.

Use no misrepresentations that communicate a false degree of relief, safety, effectiveness, or benefits of treatment.

Surgeons will be held responsible for any violations of their office or public relations firms retained.

Surgeons will be held responsible for any violations of their office or public relations firms retained.

Surgeons will make efforts to ensure that advertisements by academic institutions, hospitals, and private practices are not false or misleading.

Surgeons will make efforts to ensure that advertisements by academic institutions, hospitals, and private practices are not false or misleading.

Advertisements shall abide by state and federal laws and regulations related to professional credentials.

Advertisements shall abide by state and federal laws and regulations related to professional credentials.

Provide no false or misleading certification levels.

Provide no false or misleading certification levels.

Provide no false or misleading representation of procedure volume or academic appointments orassociations.

Provide no false or misleading representation of procedure volume or academic appointments orassociations.

Provide no false or misleading statements regarding development or study of surgical procedures.

Provide no false or misleading statements regarding development or study of surgical procedures.

6. Orthopaedist-Industry Conflicts of Interest (2007)

Surgeons shall regard their responsibility to the patient as paramount

Surgeons shall regard their responsibility to the patient as paramount

Surgeons shall prescribe drugs, devices and treatments on the basis of medical considerations, regardless of benefit from industry.

Surgeons shall prescribe drugs, devices and treatments on the basis of medical considerations, regardless of benefit from industry.

Surgeons shall be subject to discipline by AAOS Professional Compliance Program if convicted of federal or state conflict-of-interest laws.

Surgeons shall be subject to discipline by AAOS Professional Compliance Program if convicted of federal or state conflict-of-interest laws.

Surgeons shall resolve conflicts of interest in the best interest of the patient, respecting the patient’s autonomy.

Surgeons shall resolve conflicts of interest in the best interest of the patient, respecting the patient’s autonomy.

Surgeons shall notify the patient when withdrawing from a patient-physician relationship if a conflict cannot be resolved in the best interest of the patient.

Surgeons shall notify the patient when withdrawing from a patient-physician relationship if a conflict cannot be resolved in the best interest of the patient.

Surgeons shall decline subsidies or support from industry except gifts of $100 or less, medical textbooks, or educational material for patients.

Surgeons shall decline subsidies or support from industry except gifts of $100 or less, medical textbooks, or educational material for patients.

Surgeons shall disclose any relationship with an industry to colleagues, institution, and other entities.

Surgeons shall disclose any relationship with an industry to colleagues, institution, and other entities.

Surgeons shall disclose to patients any financial arrangement, including royalties, stock options, and consulting arrangements with an industry.

Surgeons shall disclose to patients any financial arrangement, including royalties, stock options, and consulting arrangements with an industry.

Surgeons shall refuse any direct financial inducement to use a particular implant, device, or drug.

Surgeons shall refuse any direct financial inducement to use a particular implant, device, or drug.

Surgeons shall enter into consulting agreements with industry only when agreements are made in advance in writing and have the following features:

Surgeons shall enter into consulting agreements with industry only when agreements are made in advance in writing and have the following features:

They include documentation of an actual need for the service.

They include documentation of an actual need for the service.

They include proof that the service was provided.

They include proof that the service was provided.

They include evidence that physician reimbursement for consulting services is consistent with fair market value.

They include evidence that physician reimbursement for consulting services is consistent with fair market value.

They are not based on the volume or value of business that the physician generates.

They are not based on the volume or value of business that the physician generates.

Surgeons shall participate only in meetings that are conducted in clinical, educational, or conference settings conducive to the effective exchange of information.

Surgeons shall participate only in meetings that are conducted in clinical, educational, or conference settings conducive to the effective exchange of information.

Surgeons shall accept no financial support to attend social functions with no educational element.

Surgeons shall accept no financial support to attend social functions with no educational element.

Surgeons shall accept no financial support to attend continuing medical education (CME) events except in the following situations:

Surgeons shall accept no financial support to attend continuing medical education (CME) events except in the following situations:

As residents and fellows when selected by and paid by their training institution or CME sponsor.

As residents and fellows when selected by and paid by their training institution or CME sponsor.

As faculty members of CME programs are allowed honoraria, travel and lodging expenses, and meals from sponsor.

As faculty members of CME programs are allowed honoraria, travel and lodging expenses, and meals from sponsor.

Surgeons shall accept only tuition, travel accommodations, and modest hospitality when attending industry-sponsored non-CME events.

Surgeons shall accept only tuition, travel accommodations, and modest hospitality when attending industry-sponsored non-CME events.

Surgeons shall accept no financial support for guests or other persons who have no professional interest in attending meetings.

Surgeons shall accept no financial support for guests or other persons who have no professional interest in attending meetings.

Surgeons shall disclose any financial relationship with regard to procedure or device when reporting clinical research and experience.

Surgeons shall disclose any financial relationship with regard to procedure or device when reporting clinical research and experience.

Surgeons shall truthfully report research results with no bias from funding sources, regardless of positive or negative findings.

Surgeons shall truthfully report research results with no bias from funding sources, regardless of positive or negative findings.

III CHILD, ELDER, AND SPOUSAL ABUSE

1. Each year, intentional violence claims 20,000 lives, is responsible for more than 300,000 hospitalizations, and causes millions of injuries.

2. It is estimated that 1.4 million children in the United States suffer some form of maltreatment each year. As many as 2000 children die each year from abuse.

1. The U.S. Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act of 1974 requires orthopaedic surgeons to report all suspected cases of child abuse to local authorities.

2. Failure to report suspected child abuse might result in state disciplinary actions.

Child protective services and social workers should be alerted, and the events and home circumstances should be investigated.

Child protective services and social workers should be alerted, and the events and home circumstances should be investigated.

These statutes provide legal immunity for physicians who report such cases, provided that they act in good faith, even if the information is protected by the physician-patient privilege.

These statutes provide legal immunity for physicians who report such cases, provided that they act in good faith, even if the information is protected by the physician-patient privilege.

1. Elder abuse has been estimated to affect 2 million older Americans each year.

2. A 1989 Congressional study indicated that 1 of every 25 Americans older than 65 years suffers some serious form of abuse, neglect, or exploitation.

3. Many states have provided legislation to protect from liability the physicians who report elder abuse.

4. Risk factors for elder abuse include increasing age, functional disability, cognitive impairment, and higher rates of child abuse within the regional population. Gender is not a risk factor.

1. One in four women experience domestic violence. Women account for 85% of the victims of intimate partner violence (men only about 15%).

2. The reporting of suspected spousal abuse is not required, and there is a corresponding absence of legal protection for physicians.

3. A physician may encourage a patient to seek self-protection. If the physician believes that an individual is truly incapable of self-protection, a court order may be obtained to permit reporting.

4. Risk factors for spousal abuse include pregnancy, women’s age of 19 to 29 years in households earning less than $10,000/year, and African-American race with low socioeconomic status.

A Importance of diversity: The understanding of the value of diversity in race, gender, creed, and sexual orientation is increasing in all areas of life.

1. It is essential to be sensitive to diversity issues with regard to colleagues in orthopaedic surgery and medicine, professionals in fields of allied medicine, and patients.

2. Other important aspects of diversity and nondiscrimination include obesity, psychiatric disease, income class, physical disability, and the status of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.

B Treatment decisions should not be made on any basis that would constitute illegal discrimination.

1. To include but not limited to race, color, gender, sexual orientation, religion, or national origin (AAOS Standards of Professionalism)

C Sensitivity to diversity issues is an increasingly important aspect of professionalism.

1. Each practitioner must examine the attitudes, preconceptions, and emotions in this dimension that are exhibited in the workplace.

2. Practitioners must be aware of how speech and behaviors might be perceived by other people of different backgrounds.

3. It is possible for the actions of someone with good intentions to be interpreted as threatening or derogatory by other people of different backgrounds.

1. Avoiding sexual misconduct is an important aspect of professionalism in relationships with patients, coworkers, staff, and colleagues.

2. Sexual relationships, even if consensual, between individuals in a professional supervisor-trainee relationship create the potential for sexual exploitation and the loss of objectivity.

B Sexual harassment in employment

1. Quid pro quo: Harassment is directly linked to employment or advancement.

2. Hostile environment harassment: Actual sexual advances are not necessary to create a hostile work environment.

Verbal or physical conduct (e.g., gestures, innuendo, humor, pictures) of a sexual nature may be interpreted as harassment.

Verbal or physical conduct (e.g., gestures, innuendo, humor, pictures) of a sexual nature may be interpreted as harassment.

General gender-based hostility that promotes a hostile environment in the workplace may be interpreted as harassment.

General gender-based hostility that promotes a hostile environment in the workplace may be interpreted as harassment.

3. “Reasonable woman” test is the adopted standard for offensive behavior. If a “reasonable woman” would have found the behavior objectionable, then harassment may have occurred.

4. Individuals in medical training programs are considered employees of the school that is training them. This status allows them to pursue harassment claims under the Civil Rights Act.

C Sexual misconduct in the patient care setting

1. Sexual misconduct with patients is a form of exploitation.

2. Such misconduct is unethical and may represent malpractice or even criminal acts of assault. Courts have maintained that a patient is unable to give meaningful consent to sexual or romantic advances by a physician. Physicians are encouraged to report instances of sexual misconduct by their colleagues.

3. Many states have laws prohibiting physicians from pursuing relationships with current or former patients.

4. The physician-patient relationship must be terminated before any romantic interest can be pursued between the two persons involved.

4. Even then, it may still be unethical if the physician exploits certain confidences, trust, or emotions learned while serving as the patient’s physician.

“Impairment” can include chemical impairment, dependence, misconduct, or incompetence.

A A surgeon (resident, fellow, or attending physician) who discovers impairment in a colleague or supervisor has the responsibility to ensure that the problem is identified and treated.

B Mechanisms exist for the proper identification and treatment of the impaired physician. Misconduct can be reported to state and local agencies.

C When reporting such incidences, the practitioner must be sure to act in good faith with reasonable evidence.

D When a patient is at risk for immediate harm, the practitioner should assert authority to relieve the impaired physician of the patient’s care and address the problem with the senior hospital staff as soon as possible.

1. Patient care skills—including the provision of “compassionate, appropriate, and effective” care—should be mastered.

2. Medical knowledge (biomedical, clinical, and cognate sciences) must be assimilated and applied to patient care.

3. Practice-based learning includes improving patient care with investigation and the appraisal of scientific evidence.

4. Interpersonal and communication skills facilitate effective and compassionate exchange of information with patients, families, and health professionals.

5. Professionalism consists of handling responsibilities while adhering to ethical principles and considering diversity issues in patient care and social services.

6. System-based practice is aided by an awareness of the larger context of medical decisions at the levels of the social, economic, and information systems.

B Residency and Guidelines of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education

Implemented by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education to address impaired performance with long duty hours

Implemented by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education to address impaired performance with long duty hours

Failure to comply can result in probation or suspension of residency accreditation.

Failure to comply can result in probation or suspension of residency accreditation.

Defined as clinical (patient care), academic, and administrative work, including time on call.

Defined as clinical (patient care), academic, and administrative work, including time on call.

Duty hours must be 80 hours or less per week averaged over a 4-week period. A 10% increase may be allowed by programs when the education value is justified by special circumstances.

Duty hours must be 80 hours or less per week averaged over a 4-week period. A 10% increase may be allowed by programs when the education value is justified by special circumstances.

One day in seven must be taken off, averaged over a 4-week period.

One day in seven must be taken off, averaged over a 4-week period.

Time on call must be no more than 1 day per every 3 days in house; there must also be a 10-hour period off duty between daily clinical duties or after being on call.

Time on call must be no more than 1 day per every 3 days in house; there must also be a 10-hour period off duty between daily clinical duties or after being on call.

Results of early evaluations of “new” duty hours have raised concern about patient safety with regard to decreased continuity of care.

Results of early evaluations of “new” duty hours have raised concern about patient safety with regard to decreased continuity of care.

C Maintenance of certification

1. Practicing orthopaedic surgeons should strive to continually improve performance.

2. Formal education beyond a surgeon’s practice is essential.

3. The American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery established a 10-year cycle:

Formal orthopaedic American Medical Association (AMA) Physician’s Recognition Award (PRA) category 1 CME credits.

Formal orthopaedic American Medical Association (AMA) Physician’s Recognition Award (PRA) category 1 CME credits.

A Research is considered “ethical” when the primary goal is to improve methods of detection or treatment of illness.

B It should be designed to produce useful, reproducible information.

C Studies should not be redundant or serve to further the interests of individuals or institutions, financially or professionally.

D Results should be reported honestly, accurately, and in a timely manner. Misrepresentation or falsifying data is unethical.

E Withholding critical information in order to protect financial interests may create an ethical conflict and jeopardize patient care.

F Sponsorship by industry has represented a potential conflict of interest or bias:

1. Specific ethical problems arise with this type of research funding.

2. However, significant developments have been made possible by their involvement, and this form of cooperative effort is gaining acceptance.

G Informed consent: Human research subjects must provide voluntary, informed consent before participating in any research protocol.

1. Their medical care must not be contingent on their participation, and they must be allowed to withdraw from the study at any time without penalty.

2. Each subject must be able to demonstrate understanding of the information and the ability to make a responsible decision.

3. The decision must be voluntary and not the result of undue pressure or influence. Consent can be voluntary and informed only when the following criteria are met:

1. According to the AAOS, the humane use of animals in research is justified in order to enhance the quality of life of both humans and animals.

2. The use of animals is ethical only when no suitable alternatives are available.

3. Experimental protocols should minimize the number of animals used, avoid abuse, and maintain all appropriate standards of animal care.

4. The approval of the Animal Care and Use Committee of the AAOS is mandatory.

I Responsibilities of the principal investigator and coauthors

1. The principal investigator remains responsible for all aspects of the research project, even when duties have been delegated to other people.

2. The principal investigator is also responsible for accurately representing the efforts of individuals or agencies involved in the research and citing contributions from other researchers or publications.

3. The coauthors must have made a significant contribution to the design of, collection of data for, and formation of the research project.

4. Each coauthor should sign an affidavit stating that he or she has reviewed the manuscript of the research report and agrees with all the results and conclusions presented therein before its publication.

5. Resident research should be conducted under the supervision of an attending surgeon. However, the attending surgeon must contribute to the work in actual fact or in a consultative capacity.

6. Scientific publications convey information that affects other research and the direct care of patients.

7. If an error in scientific method or failure to replicate results is found, the principal investigator is responsible for accurately reporting it.

J Ethical guidelines for human research are based on the duty of a physician to “promote and safeguard the health of the people.”

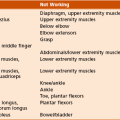

IX IMPAIRMENT, DISABILITY, AND HANDICAP

1. Loss of use or derangement of any body part, system, or function (e.g., muscle weakness, incontinence, pain, loss of joint motion, loss of body part)

2. Impairments are determined by the physician on the basis of the objective results of a physical examination.

3. In permanent impairment, the impairment has become static or well stabilized and is not likely to remit despite maximum medical treatment.

B Disability: loss of an individual’s capacity to meet personal, social, or occupational demands because of impairment

1. The gap between what a person can do and what she or he needs or wants to do

2. A disability renders a person unable to perform any kind of substantial gainful work, in view of the individual’s age, education, and work experience.

3. Permanent disability is disability that has become static or well established and is not likely to change despite medical or rehabilitative measures.

4. The provisions of the Americans with Disabilities Act apply to organizations in the private sector that employ 25 or more employees.

Accommodation refers to workplace modifications that enable a disabled employee to meet the job demands required of other workers.

Accommodation refers to workplace modifications that enable a disabled employee to meet the job demands required of other workers.

Under the Americans with Disabilities Act, the identification of an individual as having a disability does not depend on the results of a medical examination.

Under the Americans with Disabilities Act, the identification of an individual as having a disability does not depend on the results of a medical examination.

An individual may be identified as having a disability if there is a record of an impairment that has substantially limited one or more major life activities.

An individual may be identified as having a disability if there is a record of an impairment that has substantially limited one or more major life activities.

C Handicap: related to, but different from, the concepts of disability and impairment

1. Under federal law, an individual is handicapped if impairment substantially limits one or more of the activities of daily living.

A surgeon who loses a hand has an impairment and will be disabled in terms of the ability to operate.

A surgeon who loses a hand has an impairment and will be disabled in terms of the ability to operate.

However, the surgeon may be fully capable of being the chief of a hospital medical staff and may not be at all disabled with regard to that occupation.

However, the surgeon may be fully capable of being the chief of a hospital medical staff and may not be at all disabled with regard to that occupation.

The surgeon has a handicap that impairs his ability to tie shoelaces or cut steak.

The surgeon has a handicap that impairs his ability to tie shoelaces or cut steak.

section 2 Ethics and the Business of Orthopaedics

These issues best managed with full disclosure.

A When a surgeon’s financial or ownership interest in a durable medical goods provider, imaging center, surgery center, or other health care facility is not immediately obvious, the surgeon must disclose this information.

B Disclosure is important with regard to intellectual property, royalties, and devices as well.

A “Unbundling” is to bill individually for services that are properly considered a part of the “global service” package.

B For example, a surgeon does not bill separately for office visits that are ordinarily scheduled for routine postsurgical follow-up for a period of 90 days.

III REFERRALS AND OWNERSHIP OF MEDICAL SERVICES

A The Stark laws* continue to be reinterpreted and modified but apply to physicians who serve Medicare and Medicaid patients.

B Designated health services include most diagnostic and therapeutic services relevant to orthopaedic surgery.

C The Stark laws prohibit the referral of patients to entities with which the referring physician or immediate family member has a financial relationship.

D Exceptions exist for “in-house ancillary services” that are within a surgeon’s own practice. These services play specific roles.

IV RELATIONSHIP WITH INDUSTRY†

A Conflict of interest must be resolved in the best interest of the patient.

1. The surgeon’s role is to select the best possible orthopaedic hardware, medication, or treatment for a particular patient’s needs.

B Consulting and intellectual property and relationship with industry

1. This relationship has been described as being of four types:

Type I: A surgeon possesses intellectual property rights.

Type I: A surgeon possesses intellectual property rights.

Type II: A consulting agreement is based on specific expertise.

Type II: A consulting agreement is based on specific expertise.

Type III: A surgeon is compensated for product promotional activities—often an ethical violation.

Type III: A surgeon is compensated for product promotional activities—often an ethical violation.

Type IV: A surgeon is provided benefits in exchange for product use—always an ethical violation.

Type IV: A surgeon is provided benefits in exchange for product use—always an ethical violation.

A Consultation implies that the treating physician retains care for the patient; it is unethical for the consulting physician to solicit the care of a patient.

B Referral implies that the treating physician desires to share the care of the patient with a specific service.

C Transfer by the treating physician implies complete transfer of care to an accepting physician. All transfers must be made with the consent of the patient.

D Second opinions secured by third-party payers before authorization of procedures are usually governed by contractual agreements.

E Orthopaedic surgeons providing a second opinion are ethically responsible to inform the patient of all relevant facts, including instances in which surgeon error may have led to the current circumstances. However, there is no legal requirement to provide this information.

VI INSURANCE AND REIMBURSEMENT

A Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services are federal agencies that administer public health programs in the United States.

B Public health care programs were initiated as part of the Social Security Amendments of 1965 and have become some of the most important economic entities in modern health care.

C Medicare is a federal health care insurance system for individuals 65 years of age and older.

D Medicaid is a federally funded but state-administered health care insurance system for certain low-income and other individuals.

E Insurance and reimbursement tools

1. Relative value units (RVUs): system through which physicians are reimbursed for patient care.

RVUs are assigned to patient care activities in the clinic, operating room, emergency room, or interventional suite.

RVUs are assigned to patient care activities in the clinic, operating room, emergency room, or interventional suite.

The total RVU for patient care is based on the following:

The total RVU for patient care is based on the following:

Work (time, intensity, effort: about 50% of value)

Work (time, intensity, effort: about 50% of value)

Practice expense (overhead, staffing: about 45%)

Practice expense (overhead, staffing: about 45%)

Professional liability insurance (regional malpractice costs: about 5%)

Professional liability insurance (regional malpractice costs: about 5%)

The geographic practice cost index (GPCI) adjusts RVU payments by regional differences in cost of living, liability exposure, and political influences.

The geographic practice cost index (GPCI) adjusts RVU payments by regional differences in cost of living, liability exposure, and political influences.

The RVU calculation for thousands of codes and procedures is complex.

The RVU calculation for thousands of codes and procedures is complex.

Both government and physician groups throughout the AMA are represented in determining updates.

Both government and physician groups throughout the AMA are represented in determining updates.

2. Diagnosis-related groups (DRGs): system by which hospitals are reimbursed for patient care.

For example, DRG 209 represents hospitalization that includes total knee and total hip arthroplasty.

For example, DRG 209 represents hospitalization that includes total knee and total hip arthroplasty.

3. Gain-sharing: an incentive plan in which both surgeon and hospital are encouraged to increase efficiency and lower costs

The high, and increasing, cost of implants is often the first target of these programs.

The high, and increasing, cost of implants is often the first target of these programs.

Ethical concerns and legality of gain-sharing are frequently discussed by the powerful stakeholders, including implant manufacturers and hospitals.

Ethical concerns and legality of gain-sharing are frequently discussed by the powerful stakeholders, including implant manufacturers and hospitals.

4. Pay for performance (P4P): a trend in reimbursement and quality assurance whose goal is to reimburse efforts to standardize patient care

Government, private insurers, or professional organizations define quality measures.

Government, private insurers, or professional organizations define quality measures.

The time when measures are met may entitle surgeons, hospitals, or both to increase payments or to avoid fines.

The time when measures are met may entitle surgeons, hospitals, or both to increase payments or to avoid fines.

Quality measures include either process of care goals (e.g., preoperative prophylactic antibiotic orders) or outcome measurements (e.g., decrease rates of infection).

Quality measures include either process of care goals (e.g., preoperative prophylactic antibiotic orders) or outcome measurements (e.g., decrease rates of infection).

A Wide-ranging, unpredictable, and frequently difficult-to-treat pathologic processes in patients who display assorted levels of compliance

B Economic components, including higher percentages of underinsured patients

C Markedly smaller payer reimbursements in the presence of unrelenting increases in overhead costs

D Night calls, which may interfere with a productive elective schedule during the day

E Attitudes of younger surgeons toward work

F Lifestyle issues and changing perception of parental duties in modern two-income families

G Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA): places the responsibility to provide emergency services on the hospital

1. EMTALA laws govern how hospitals treat and transfer patients presenting with unstable medical conditions.

These laws are sometimes called “antidumping” laws.

These laws are sometimes called “antidumping” laws.

In general, hospitals must evaluate any patient and “stabilize” an unstable medical condition, regardless of the patient’s ability to pay.

In general, hospitals must evaluate any patient and “stabilize” an unstable medical condition, regardless of the patient’s ability to pay.

2. EMTALA applies to hospitals that provide emergency services to Medicare and Medicaid patients and applies to nearly all hospitals.

The regulations apply to all patients at such hospitals, not just Medicare patients.

The regulations apply to all patients at such hospitals, not just Medicare patients.

Any patient who comes to the emergency room requesting treatment must receive a screening examination to identify a possible emergency condition.

Any patient who comes to the emergency room requesting treatment must receive a screening examination to identify a possible emergency condition.

A patient in whom an emergency condition exists must receive treatment until the condition is “stabilized” or until transfer or discharge is unlikely to result in deterioration of the condition.

A patient in whom an emergency condition exists must receive treatment until the condition is “stabilized” or until transfer or discharge is unlikely to result in deterioration of the condition.

Once the patient’s condition is stabilized, the patient may be transferred if the benefits of transfer outweigh the risks (documented) and the receiving institution accepts the transfer.

Once the patient’s condition is stabilized, the patient may be transferred if the benefits of transfer outweigh the risks (documented) and the receiving institution accepts the transfer.

3. EMTALA does not force orthopaedists to provide emergency services or to be on call.

Orthopaedists in every community have a responsibility to ensure that emergency patients receive appropriate and timely musculoskeletal care.

Orthopaedists in every community have a responsibility to ensure that emergency patients receive appropriate and timely musculoskeletal care.

Local strategies must be employed by the orthopaedic surgeons and hospitals in each community.

Local strategies must be employed by the orthopaedic surgeons and hospitals in each community.

Surgeons may be in violation of EMTALA in the following situations:

Surgeons may be in violation of EMTALA in the following situations:

4. EMTALA does force hospitals to provide emergency care to patients.

Hospitals may fulfill their obligation by contracts with physicians or groups of physicians or by requirements in the hospital bylaws.

Hospitals may fulfill their obligation by contracts with physicians or groups of physicians or by requirements in the hospital bylaws.

A growing trend exists for hospitals to hire surgeons directly, to pay for care that surgeons provide to uninsured patients, or to provide a stipend for covering the hospital’s obligation.

A growing trend exists for hospitals to hire surgeons directly, to pay for care that surgeons provide to uninsured patients, or to provide a stipend for covering the hospital’s obligation.

According to the AAOS position, hospitals are obligated to assume a portion of the growing costs of providing emergency care.

According to the AAOS position, hospitals are obligated to assume a portion of the growing costs of providing emergency care.

5. The law is unclear in scenarios involving follow-up care.

An “on-call” orthopaedist who either sees the patient or formulates a plan of care without seeing the patient has established a relationship.

An “on-call” orthopaedist who either sees the patient or formulates a plan of care without seeing the patient has established a relationship.

This does not constitute a clear obligation to provide follow-up care under EMTALA once the patient’s condition has been stabilized.

This does not constitute a clear obligation to provide follow-up care under EMTALA once the patient’s condition has been stabilized.

However, the law may be interpreted in different ways, and the orthopaedist may have some obligation for ongoing care regardless of the patient’s ability to pay.

However, the law may be interpreted in different ways, and the orthopaedist may have some obligation for ongoing care regardless of the patient’s ability to pay.

It is in the best interests of the hospital, the orthopaedic surgeon, and the community to provide adequate compensation for unfunded care from the emergency room.

It is in the best interests of the hospital, the orthopaedic surgeon, and the community to provide adequate compensation for unfunded care from the emergency room.

section 3 Ethics and Medicolegal Issues

A Informed consent is a process (not simply a document) representing an exchange of information that results in the selection of and agreement to undergo a specific form of treatment.

B Without proper consent from a patient or a patient’s family, the surgeon may be guilty of an assault, battery, or trespass against the patient.

C Most litigation results from unexpected consequences of a procedure.

D Properly informed patients are aware of, and have decided to accept, both the potential for benefits and the risks.

E The attending surgeon should explain to patient (or legal representative) in layperson’s terms the following information:

1. The patient’s diagnosis and the nature of the condition or illness necessitating intervention

2. The nature and purpose of the proposed treatment or procedural plan

3. The risks and complications of the treatment or procedure

4. Options or alternatives (including no treatment), with their associated risks and complications

5. The probability of success (no guarantee of success should be expressed or implied)

F In elective cases, informed consent should ideally be obtained by the physician in the office setting several days before surgery.

G A patient (or legal representative) must have adequate decision-making capacity.

H A professional translator should be present for patients who do not speak the same language as the physician. Avoid using a family member for translation whenever possible.

I If a patient lacks the ability to make decisions, informed consent may be obtained by a legal guardian or, in situations deemed medically necessary, by a physician.

J Special rules about informed consent apply in cases of emergencies and to minors.

1. A medical emergency concerns an unconscious or incapacitated person with a life- or limb-threatening condition that necessitates immediate medical attention.

Treatment can proceed without informed consent; as soon as is practical, the reason for treatment should be documented.

Treatment can proceed without informed consent; as soon as is practical, the reason for treatment should be documented.

2. Consent rules for minors vary greatly from state to state. The surgeon must be aware of the rules that apply locally.

K Documentation of consent is usually in the form of a hospital “permit” and a summary note in the patient’s record (which constitute so-called double consent).

L Standards of disclosure: The degree of disclosure varies among the states, and the courts have developed two standards that may be applied.

1. Professional or reasonable physician standard: used by most states, based on what is customary practice in a specific medical community for surgeons to divulge to their patients.

2. Patient viewpoint standard: based on the level of information that a “reasonable person” would want to know in a similar circumstance. (This viewpoint has received some preference in courts.)

“Physician-patient relationship has a contractual basis and is based on confidentiality, trust, and honesty” (AAOS Code of Medical Ethics).

A Both the patient and the orthopaedic surgeon are free to enter or discontinue the relationship within any existing constraints of a contract with a third party.

B An orthopaedic surgeon has an obligation to render care only for the conditions that he or she is competent to treat.

1. The contract starts when a physician actually sees a patient in an office visit or hospital consultation.

2. Orthopaedic surgeons do have an obligation to adhere to the “standard of care,” although this concept is hard to define precisely:

What a “reasonable” orthopaedic surgeon might do under similar circumstances

What a “reasonable” orthopaedic surgeon might do under similar circumstances

Often considered to be regional or local in nature, but several legal cases have been decided on the notion of a national standard of care.

Often considered to be regional or local in nature, but several legal cases have been decided on the notion of a national standard of care.

A complex concept that is often determined on a case-by-case basis

A complex concept that is often determined on a case-by-case basis

It is not ethical or legal to offer substandard care to a patient who is perceived as undesirable.

It is not ethical or legal to offer substandard care to a patient who is perceived as undesirable.

A physician is not required to provide therapy that is found to be ethically inappropriate or medically ineffective.

A physician is not required to provide therapy that is found to be ethically inappropriate or medically ineffective.

3. Terminating the physician-patient contract: Once a relationship has been established, it is expected that the relationship will continue except under certain circumstances:

Physicians must always provide emergency treatment to patients.

Physicians must always provide emergency treatment to patients.

Physicians may terminate the relationship for patients who can no longer pay for services, as long as an alternative source of care can be identified.

Physicians may terminate the relationship for patients who can no longer pay for services, as long as an alternative source of care can be identified.

When an alternative source cannot be identified, caution must be exercised in terminating the relationship.

When an alternative source cannot be identified, caution must be exercised in terminating the relationship.

Even for nonemergency care, there is debate over whether an orthopaedist may terminate care because of a patient’s inability to pay.

Even for nonemergency care, there is debate over whether an orthopaedist may terminate care because of a patient’s inability to pay.

Identifying an alternative source of care is best accomplished in writing and should provide the patient with ample time to establish care with the new provider.

Identifying an alternative source of care is best accomplished in writing and should provide the patient with ample time to establish care with the new provider.

This situation also applies if an orthopaedic surgeon withdraws from a managed care contract or no longer accepts an insurance plan.

This situation also applies if an orthopaedic surgeon withdraws from a managed care contract or no longer accepts an insurance plan.

Medical records should be forwarded to the accepting physician, including a medical history and a summary of the treatment rendered.

Medical records should be forwarded to the accepting physician, including a medical history and a summary of the treatment rendered.

Wrongful termination of the physician-patient relationship consists of four basic elements:

Wrongful termination of the physician-patient relationship consists of four basic elements:

The physician-patient relationship must be established.

The physician-patient relationship must be established.

Patient must have a reasonable expectation that care will be provided.

Patient must have a reasonable expectation that care will be provided.

Patient must have a medical need that necessitates medical attention, the absence of which will result in harm or injury.

Patient must have a medical need that necessitates medical attention, the absence of which will result in harm or injury.

Causation must be established. The failure to provide care must produce injury or harm.

Causation must be established. The failure to provide care must produce injury or harm.

Abandonment may take many forms.

Abandonment may take many forms.

Inadequate follow-up for common complications to be recognized

Inadequate follow-up for common complications to be recognized

Failure to provide an appointment to an established patient, even if the patient has not paid previous bills, has missed other appointments, has been noncompliant, or has sought interim care from another provider

Failure to provide an appointment to an established patient, even if the patient has not paid previous bills, has missed other appointments, has been noncompliant, or has sought interim care from another provider

Premature discharge from an inpatient setting

Premature discharge from an inpatient setting

Failure to allow the patient the opportunity to seek care elsewhere when physician has illness, personal conflict, or vacation

Failure to allow the patient the opportunity to seek care elsewhere when physician has illness, personal conflict, or vacation

If a patient does not appear for important follow-up appointments, a certified letter should be sent instructing him or her to attend follow-up appointments.

If a patient does not appear for important follow-up appointments, a certified letter should be sent instructing him or her to attend follow-up appointments.

5. Scope of practice: “An orthopaedic surgeon should practice only within the scope of his or her personal education, training, and experience” (AAOS Code of Medical Ethics).

A Crisis and reform: It is commonly accepted that there is an ongoing crisis in medical liability that threatens the well-being of patients and physicians alike.

1. States whose politicians have reformed policies are rewarded with increasing numbers of physicians.

B Malpractice: negligence by a health care provider that results in injury to a patient

1. Malpractice suit: a civil action filed by a patient alleging that a physician’s negligence resulted in an injury for which the patient desires compensation

2. Issues with physician-patient communication are frequently cited as the most common factor in the initiation of a malpractice lawsuit.

3. In general, if an error is discovered by the surgeon (such as use of an incorrect implant), it should be disclosed to the patient.

4. Femur fractures (particularly pediatric fractures), followed by tibia fractures, are the orthopaedic conditions that most commonly result in malpractice suits. Displacement of an intervertebral disk is third most common, but it has the highest indemnity, both total and average.

5. The law requires proof of the allegation by a preponderance of the evidence.

C Negligence: the result of failure to exercise the degree of diligence and care that a reasonable and prudent person would exercise under the same or similar conditions. Medical negligence comprises four elements: duty, breach of duty, causation, and damages.

1. Duty begins when the surgeon offers to treat the patient and the patient accepts the offer.

The duty of the physician is to provide care equal to the same standard of care ordinarily executed by surgeons in the same medical specialty.

The duty of the physician is to provide care equal to the same standard of care ordinarily executed by surgeons in the same medical specialty.

There is no particular “institution” standard of care; the standard of care is usually established by expert testimony.

There is no particular “institution” standard of care; the standard of care is usually established by expert testimony.

Validity of testimony: The testimony must be nonpartisan, scientifically correct, and clinically accurate.

Validity of testimony: The testimony must be nonpartisan, scientifically correct, and clinically accurate.

Basis for testimony must be documented (personal experience, clinical references, and currently accepted orthopaedic opinion).

Basis for testimony must be documented (personal experience, clinical references, and currently accepted orthopaedic opinion).

Ethics and requirements to testify (see earlier discussion of Standards of Professionalism, Orthopaedic Expert Witness Testimony):

Ethics and requirements to testify (see earlier discussion of Standards of Professionalism, Orthopaedic Expert Witness Testimony):

Reasonable compensation commensurate with time and expertise is acceptable; compensation based on the outcome of the litigation is unethical.

Reasonable compensation commensurate with time and expertise is acceptable; compensation based on the outcome of the litigation is unethical.

Res ipsa loquitur (“the thing speaks for itself”): Certain cases do not require expert testimony.

Res ipsa loquitur (“the thing speaks for itself”): Certain cases do not require expert testimony.

When surgery is performed at the wrong site, when surgical equipment is inadvertently left inside the patient, and when a physician fails to attend to a patient in distress who complains persistently.

When surgery is performed at the wrong site, when surgical equipment is inadvertently left inside the patient, and when a physician fails to attend to a patient in distress who complains persistently.

Residents and fellows are held to the same standard of care as that for board-certified orthopaedists.

Residents and fellows are held to the same standard of care as that for board-certified orthopaedists.

2. Breach of duty: when action or failure to act deviates from the standard of care

Breach of duty takes the form of an act of commission (doing what should not have been done) or an act of omission (failing to do what should have been done).

Breach of duty takes the form of an act of commission (doing what should not have been done) or an act of omission (failing to do what should have been done).

3. Causation: when failure to meet the standard of care was the direct cause of the patient’s injuries

4. Damages: monies awarded as compensation for injuries sustained as the result of medical negligence

Special damages are actual expenses, such as medical or rehabilitative expenses and lost wages.

Special damages are actual expenses, such as medical or rehabilitative expenses and lost wages.

General damages, or noneconomic losses, are awards for pain and suffering, disfigurement, and other adverse outcomes.

General damages, or noneconomic losses, are awards for pain and suffering, disfigurement, and other adverse outcomes.

Punitive or exemplary damages serve as a penalty for blatant disregard or incompetence. (Seldom awarded in medical malpractice cases.)

Punitive or exemplary damages serve as a penalty for blatant disregard or incompetence. (Seldom awarded in medical malpractice cases.)

Ad quod damnum clause specifies the amount of money sought for damages in a suit. (not allowed in some states)

Ad quod damnum clause specifies the amount of money sought for damages in a suit. (not allowed in some states)

D Comparative negligence doctrine awards damages that are based on the percentage of responsibility for the result by each party.

E Contributory negligence bars the recovery of damages if there was negligence on the part of the plaintiff.

F Modified comparative fault bars the recovery of damages if the plaintiff’s contributory negligence exceeds 50%.

G Bad faith action: When a claim is filed and an action pursued regardless of the lack of reasonable grounds for filing the claim. In these circumstances, the physician may countersue for damages.

H Statute of limitations: time limit for plaintiff to file a malpractice suit

1. In general, 2 years (the time limit varies by state)

2. For minors, generally 2 years from the time of the incident or until the individual’s eighteenth birthday.

I Discovery: the process by which both parties find out about each other’s cases and is a period of information gathering

1. Occurrence coverage covers claims resulting from action that occurs during the coverage period of policy, regardless of when the claim is filed.

Very expensive; coverage extends even after physician stops work (i.e., so-called tail insurance is included).

Very expensive; coverage extends even after physician stops work (i.e., so-called tail insurance is included).

2. Claims-made coverage covers claims resulting from action that occurs during the policy period that are reported during policy period.

1. Tail coverage is a separate policy that covers the physician for all claims made for actions occurring during the period of coverage; this essentially constitutes an occurrence policy.

2. Prior-act coverage protects the insured physician from potential claims resulting from events for which claims have yet to be filed.

3. Locum tenens coverage provides extended insurance coverage to a physician who temporarily replaces the policyholder.

4. Slot coverage covers duties encountered during practice in a specific position through which several physicians may rotate.

C Policies may have specific restrictions or exclusions

1. Some policies cover only direct patient care.

2. Activities such as peer review, quality assurance, and utilization review may be covered by the insurance policy or a health care contract.

3. Nearly all policies for residents and fellows have an exclusion for moonlighting.

Ensure that your employer provides such coverage, or purchase professional liability insurance in your own behalf.

Ensure that your employer provides such coverage, or purchase professional liability insurance in your own behalf.

4. Hold harmless clause is a contractual statement that attempts to shift liability from the employer to the physician. Insurance carriers do not generally cover this contractual obligation.

D Surcharging or experience rating: Insurance plans may assess points against a physician on the basis of the number of claims filed and the dollar amounts awarded on behalf of the insured.

E Good Samaritan Act: This act grants legal immunity for actions performed in good faith by persons at the scene of an emergency.

1. Legal immunity is not given if the action constitutes gross, willful, or wanton neglect.

2. It does not extend to care given in expectation of payment by persons who routinely render care in an emergency room or by the patient’s admitting, attending, or treating physician.

F The AAOS recommends that a resident or fellow make a point of obtaining evidence of insurance for each year of residency and saving this evidence in personal files.

V LIABILITY STATUS OF RESIDENTS AND FELLOWS

A Residents and fellows are licensed physicians who function as employees while in a training or educational program.

B This creates a special relationship between them and their patients and supervisors.

C Disclosure to patients: Failure to inform a patient of residency or fellow status may result in claims of fraud, deceit, misrepresentation, assault, battery, and lack of informed consent.

1. Residents and fellows are responsible for their own actions.

2. Supervisors may be held accountable for the actions of the residents and fellows. This is known as vicarious liability.

3. Respondeat superior (“Let the master answer”): This doctrine is also known as “borrowed servant” or the “captain of the ship.”

An agency relationship is established by the fact that the resident or fellow has been authorized to act for or represent the supervising physician.

An agency relationship is established by the fact that the resident or fellow has been authorized to act for or represent the supervising physician.

While the resident or fellow is an agent for the supervisor, all acts of the relationship are considered to be under the direction of the supervisor.

While the resident or fellow is an agent for the supervisor, all acts of the relationship are considered to be under the direction of the supervisor.

This relationship is independent of the specific employer of the resident or fellow.

This relationship is independent of the specific employer of the resident or fellow.

4. Residents and fellows are held to the same standard of care as a fully trained, practicing orthopaedist, regardless of their level of training.

E The AAOS recommends that residents and fellows retain permanent documentation regarding the resolution of any adverse decision in which they may be named.

F Adverse decisions are reported to the National Practitioner Data Bank, and the resulting information is made available to all health care facilities, as is information about any pending litigation.

G Documentation regarding the individual cases and information on the resolution of adverse decisions is necessary when the resident or fellow seeks privileges at any health care facility.

These are a systematic documentation of a patient’s individual medical history and care.

A Primary purpose: to allow continuity of care and communication between providers

B Whether used in legal proceedings or not, the medical record is a legal document.

C It is a business and administrative document justifying appropriate reimbursement when available.

D The following statements cover several legal and practical aspects of the medical record:

1. The data in medical records belong to the patient (who may request copies at reasonable cost).

2. Medical records represent the best defense in a malpractice lawsuit.

Medical records must be maintained for 7 years after the last date of treatment.

Medical records must be maintained for 7 years after the last date of treatment.

Medical records are confidential and, without the patient’s written approval, cannot be reproduced or discussed with parties not involved in treating the patient.

Medical records are confidential and, without the patient’s written approval, cannot be reproduced or discussed with parties not involved in treating the patient.

3. Accurate and complete medical records protect both the patient and physician from errors and misinterpretations. Records should be characterized as follows:

Well-documented, detailing the history, observations, reasons for the treatment provided, and patient noncompliance

Well-documented, detailing the history, observations, reasons for the treatment provided, and patient noncompliance

Accurate and should properly identify the patient

Accurate and should properly identify the patient

A logical sequence of the events and factors affecting treatment decisions

A logical sequence of the events and factors affecting treatment decisions

An outline of the treatment plan, including the risks, benefits, and alternatives

An outline of the treatment plan, including the risks, benefits, and alternatives

Free from editorial comments or casual criticism of the patient or other health care providers

Free from editorial comments or casual criticism of the patient or other health care providers

4. Medical records should never be altered.

All corrections should be made by amendments. These amendments should accurately reflect the reason for correction and be placed after the last entry.

All corrections should be made by amendments. These amendments should accurately reflect the reason for correction and be placed after the last entry.

An errant entry should be lined through so that it remains legible. The reason for the correction, the date, the time, and the physician’s initials must be included.

An errant entry should be lined through so that it remains legible. The reason for the correction, the date, the time, and the physician’s initials must be included.

Removing or obscuring an entry shatters credibility and is indefensible.

Removing or obscuring an entry shatters credibility and is indefensible.

Attempts to supplement or clarify entries after notification of a lawsuit constitute tampering.

Attempts to supplement or clarify entries after notification of a lawsuit constitute tampering.

5. On notification of a complaint or lawsuit, the medical records should be secured, inventoried, and copied.

Copies of the medical record must be made available to the patient or the attorney in a reasonable amount of time.

Copies of the medical record must be made available to the patient or the attorney in a reasonable amount of time.

The medical record must not be withheld as ransom for outstanding bills.

The medical record must not be withheld as ransom for outstanding bills.

6. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA): federal security and privacy laws that regulate the disclosure of a patient’s personal medical records

Practices must develop specific policies on the use of private patient information.

Practices must develop specific policies on the use of private patient information.

In order for practices to release the private information, patients must sign notices that describe the policies.

In order for practices to release the private information, patients must sign notices that describe the policies.

Patients must authorize the release of their medical information before the information is released to a business for purposes not related to their health care (e.g., life insurer, bank, marketing firm).

Patients must authorize the release of their medical information before the information is released to a business for purposes not related to their health care (e.g., life insurer, bank, marketing firm).

Testable Concepts

Section 1 Principles of Practice

• Advertising must not suggest that treatment is without risk or that one treatment is appropriate for all patients. Misrepresentations that that communicate a false degree of relief, safety, effectiveness, or benefits of treatment (e.g., “pain-free surgery”) must not be made.

• Financial support to attend CME events is restricted to faculty members only. They are permitted to accept only tuition, travel accommodations, and modest hospitality when attending industry-sponsored non-CME events.

• The reporting of abuse varies by age and type.

• Child abuse must be reported in all states, and failure to report may result in state disciplinary actions. Legal immunity is also provided for such reporting.

• However, the reporting of suspected spousal abuse is not required, and there is a corresponding absence of legal protection for physicians who report it.

• Requirements for reporting elder abuse are inconsistent; only some states mandate reporting. Provision of legal immunity is also inconsistent.

• A surgeon (resident, fellow, or attending physician) who discovers impairment in a colleague or supervisor has the responsibility to ensure that the problem is identified and treated. When a patient is at risk for immediate harm, the surgeon should assert authority to relieve the impaired physician of the patient care and address the problem with the senior hospital staff as soon as possible.

Section 2 Ethics and the Business of Orthopaedics

• When a surgeon’s financial or ownership interest in a durable medical goods provider, imaging center, surgery center, or other health care facility is not immediately obvious, the surgeon must disclose this information.

• Disclosure is important with regard to intellectual property, royalties, and device.

• Orthopaedic surgeons providing a second opinion are ethically responsible to inform the patient of all relevant facts, including instances in which surgeon error may have led to the current circumstances. However, there is no legal requirement to provide this information.

• EMTALA places the responsibility to provide emergency services on the hospital. It does not force orthopaedists to provide emergency services.

• A patient in whom an emergency condition exists must receive treatment until the condition is “stabilized” or until transfer or discharge is unlikely to result in deterioration of the condition.

• Once the patient’s condition is stabilized, the patient may be transferred if the benefits of transfer outweigh the risks (documented) and the receiving institution accepts the transfer.

Section 3 Ethics and Medicolegal Issues

• In elective cases, informed consent should ideally be obtained by the physician in the office setting several days before surgery.

• A professional translator should be present for patients who do not speak the same language as the physician. Avoid using a family member for translation whenever possible.

• In general, consent for treatment of minors is obtained from the parent or guardian for all conditions except emergencies.

• A medical emergency concerns an unconscious or incapacitated person with a life- or limb-threatening condition that necessitates immediate medical attention. Treatment can proceed without informed consent; as soon as is practical, the reason for treatment should be documented.

• Issues with physician-patient communication are frequently cited at the most common factor in the initiation of a malpractice lawsuit.