Principles of Infection Prevention and Control

After reading this chapter you will be able to:

Define health care–associated infections and state how often they occur.

Define health care–associated infections and state how often they occur.

Describe why infection prevention is important in respiratory care.

Describe why infection prevention is important in respiratory care.

Identify and describe the three elements that must be present for transmission of infection within a health care setting.

Identify and describe the three elements that must be present for transmission of infection within a health care setting.

List the factors associated with an increased risk of a patient acquiring a nosocomial infection.

List the factors associated with an increased risk of a patient acquiring a nosocomial infection.

State the three major routes for transmission of human sources of pathogens in the health care environment.

State the three major routes for transmission of human sources of pathogens in the health care environment.

Describe strategies to control the spread of infection in the hospital.

Describe strategies to control the spread of infection in the hospital.

Describe how to select and apply chemical disinfectants for processing respiratory care equipment.

Describe how to select and apply chemical disinfectants for processing respiratory care equipment.

Describe equipment-handling procedures that help prevent the spread of pathogens.

Describe equipment-handling procedures that help prevent the spread of pathogens.

State when to use general barrier measures during patient care.

State when to use general barrier measures during patient care.

Health care–associated infections (HAIs) are infections that patients acquire during the course of medical treatment. In 2002, there were an estimated 1.7 million HAIs in U.S. hospitals accounting for 99,000 excess deaths.1 Approximately 5% of all patients admitted to a hospital develop an HAI, and 15% of HAIs are pneumonias.2,3 Approximately 25% of patients undergoing mechanical ventilation develop pneumonia as a complication, and approximately 30% of these patients die as a result of lung infection.4

The seminal Institute of Medicine report identified that medical errors may be the fifth leading cause of death in the United States, with up to 100,000 deaths annually.3 At the present time, there is increasing legislative and regulatory interest in patient safety, including a focus on HAIs. Health care professionals are giving increased attention to handwashing and protecting patients against infection. The emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in China in 2002 and global spread with outbreaks in health care settings and transmission to large numbers of health care personnel and patients underscore the importance of consistent adherence to infection control precautions. Similarly, infection control practices were tested in 2009 by pandemic H1N1 influenza A, reinforcing the reality that new challenges continually arise.

Spread of Infection

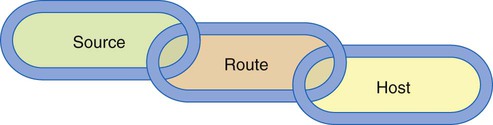

Three elements must be present for transmission of infection within a health care setting: (1) a source (or reservoir) of pathogens, (2) a susceptible host, and (3) a route of transmission for the pathogen (Figure 4-1).2

Susceptible Hosts

Hospital-acquired or nosocomial infections are infections that are acquired in the hospital. The high incidence of nosocomial gram-negative bacterial pneumonia is associated with factors that promote colonization of the pharynx with these organisms. Gram-negative colonization dramatically increases in critically ill patients, which increases the likelihood of the development of these pneumonias.4 Most nosocomial pneumonias occur in surgical patients, especially patients who have had chest or abdominal procedures. In these patients, normal swallowing and clearance mechanisms are impaired, allowing bacteria to enter and remain in the lower respiratory tract. Intubations, anesthesia, surgical pain, and use of narcotics and sedatives impair host defenses further. The risk of pneumonia is not the same for all surgical patients. Patients at the highest risk include elderly patients, severely obese patients, patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or a history of smoking, and patients with an artificial airway in place for long periods.5

Modes of Transmission

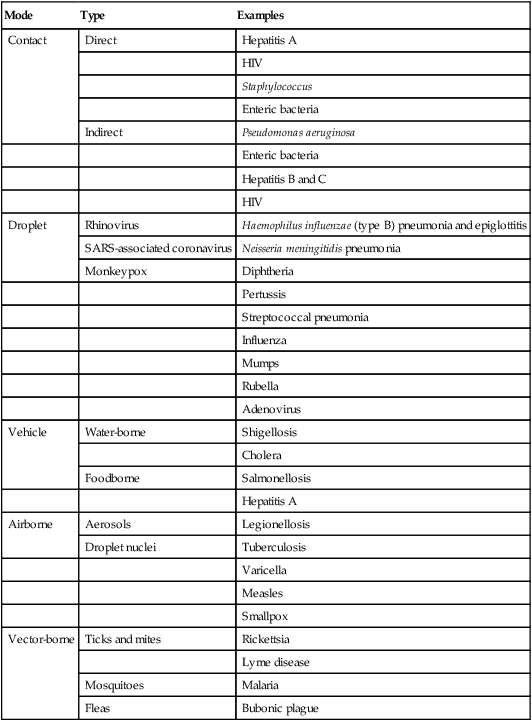

The three major routes for transmission of human sources of pathogens in the health care environment are contact (direct and indirect), respiratory droplets, and airborne droplet nuclei (respirable particles <5 µm). Table 4-1 provides examples of the common transmission routes for selected microorganisms.6

TABLE 4-1

Routes of Infectious Disease Transmission

| Mode | Type | Examples |

| Contact | Direct | Hepatitis A |

| HIV | ||

| Staphylococcus | ||

| Enteric bacteria | ||

| Indirect | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | |

| Enteric bacteria | ||

| Hepatitis B and C | ||

| HIV | ||

| Droplet | Rhinovirus | Haemophilus influenzae (type B) pneumonia and epiglottitis |

| SARS-associated coronavirus | ||

| Neisseria meningitidis pneumonia | ||

| Monkeypox | Diphtheria | |

| Pertussis | ||

| Streptococcal pneumonia | ||

| Influenza | ||

| Mumps | ||

| Rubella | ||

| Adenovirus | ||

| Vehicle | Water-borne | Shigellosis |

| Cholera | ||

| Foodborne | Salmonellosis | |

| Hepatitis A | ||

| Airborne | Aerosols | Legionellosis |

| Droplet nuclei | Tuberculosis | |

| Varicella | ||

| Measles | ||

| Smallpox | ||

| Vector-borne | Ticks and mites | Rickettsia |

| Lyme disease | ||

| Mosquitoes | Malaria | |

| Fleas | Bubonic plague |

Droplet Transmission

Droplet transmission is a form of contact transmission, but the mechanism of transfer of the pathogen is distinct, and additional prevention measures are required. Organisms that are transmitted by respiratory droplets include influenza and Neisseria meningitidis. Respiratory droplets are generated when an infected individual discharges large contaminated liquid droplets into the air by coughing, sneezing, or talking. Respiratory droplets are also generated during procedures such as suctioning, bronchoscopy, and cough induction. Transmission occurs when infectious droplets are propelled (usually ≤3 feet through the air) and are deposited on another person’s mouth or nose. Using the distance of 3 feet or less as a threshold for donning a mask has been effective in preventing transmission of infectious agents. However, experimental studies with smallpox and investigations of outbreaks of SARS suggest that droplets from infected patients rarely are able to reach a person 6 feet away.7 A distance of 3 feet or less around the patient is considered a short distance and is not used as a criterion for deciding when a mask should be donned to protect from exposure. Current Health Care Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC) guidelines state it may be prudent to don a mask when within 6 feet of a patient or on entry into the room of a patient who is on droplet isolation.6

Airborne Transmission

Airborne transmission occurs via the spread of airborne droplet nuclei. These are small particles (≤5 µm) of evaporated droplets containing infectious microorganisms that can remain suspended in air for long periods. Microorganisms carried in this manner may be dispersed widely by air currents because of their small size and inhaled by susceptible hosts over a longer distance from the source patient compared with droplet transmission. Examples of pathogens transmitted via the airborne route include Mycobacterium tuberculosis, varicella-zoster virus (chickenpox), and rubeola virus (measles). Airborne transmission of variola (smallpox) has been documented, and airborne transmission of SARS, monkeypox, and viral hemorrhagic fever virus has been reported, although it has not been proved conclusively.6

Special air handling and ventilation and respiratory protection are required to prevent airborne transmission because microorganisms may remain suspended in air and be widely dispersed by air currents before contacting a susceptible host. In addition to airborne infection isolation rooms, personal respiratory protection with National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH)–approved N-95 or higher respirators is required to prevent airborne transmission.6 A surgical mask, used for droplet precautions, is insufficient.

Miscellaneous Types of Aerosol Transmission

Three novel categories of aerosol transmission have been proposed following investigations of SARS transmission, as follows6:

Obligate transmission: Under natural conditions, disease occurs after transmission of the microorganism through small-particle aerosols.

Preferential transmission: Natural infection results from transmission through multiple routes, but small-particle aerosols predominate.

Opportunistic transmission: Microorganisms that cause disease through other routes but under certain environmental conditions may be transmitted via fine-particle aerosol (e.g., SARS transmission via an aerosol plume that originated from sewage in the Amoy Gardens housing complex).7

Infection Prevention Strategies

Creating a Safe Culture

Decreasing Host Susceptibility

Decreasing inherent host susceptibility to infection is the most difficult and least feasible approach to infection control. Hospital efforts at this level focus mainly on employee immunization and chemoprophylaxis. Certain immunizations are recommended for susceptible health care personnel to decrease the risk of infection and the potential for transmission to patients and coworkers within the health care facility. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) mandates that employers offer hepatitis B vaccination. Vaccinations of health care workers in the absence of evidence of immunity against varicella, rubella, and measles should be encouraged.8 In addition, health care personnel in facilities that care for young infants and children should receive the adult acellular pertussis vaccine. Health care personnel without medical contraindications should also receive an annual influenza vaccination.9

Antimicrobial agents and topical antiseptics may be used to prevent outbreaks of selected pathogens. Postexposure chemoprophylaxis is recommended under defined circumstances for Bordetella pertussis (whooping cough), N. meningitidis (meningococcal meningitis), Bacillus anthracis (anthrax), influenza virus, HIV, and group A streptococci.6

A large percentage of HAIs are due to device-related infections, including ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), catheter-related bloodstream infection, and catheter-associated urinary tract infection. The best way to decrease host susceptibility to a device-related infection is first to limit device use and second to ensure that devices are placed and maintained appropriately. Prevention bundles—defined as the use of multiple different evidence-based best practices to prevent device-related infection—have been shown to decrease the incidence of HAIs significantly.10,11 Boxes 4-1 and 4-2 list the components of the central line bundle for vascular catheter placement and the VAP bundle. Institutions should be committed to these processes of care, and individual health care workers should be familiar with these practices and execute them on a routine basis.12,13

Interrupting Transmission

General sanitation measures and equipment processing have limits. To prevent the spread of infections between patients and to keep themselves healthy, health care personnel also must take measures to stop infection. There are two tiers of HICPAC and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) transmission precautions: standard precautions and transmission-based precautions.6

Standard Precautions

The application of standard precautions by health care personnel during patient care depends on the nature of the interaction and the extent of anticipated blood, body fluid, or pathogen contact. For some patient care situations, only gloves are required. In other cases, gloves, gowns, and face shield may be required. Box 4-3 describes standard precautions, including hand hygiene; use of gloves, masks, and eye protection; equipment handling; and patient placement.

Hand Hygiene

The importance of hand hygiene to reduce the transmission of infectious agents cannot be overemphasized and is an essential element of standard precautions.14 Hand hygiene includes handwashing with either plain or antiseptic-containing soap and water for at least 15 seconds and the use of alcohol-based products (gels, rinses, and foams) containing an emollient that does not require the use of water. In the absence of visible soiling of hands, approved alcohol-based products are preferred over antimicrobial or plain soap and water because of their superior microbicidal activity, reduced drying of skin, and convenience. The quality of performing hand hygiene can be affected by the type and length of fingernails and by wearing jewelry. Artificial fingernails and extenders are discouraged because of their association with infections.14 Figure 4-2 illustrates the proper technique for handwashing.

Gloves

Gloves protect both patients and health care workers from exposure to pathogens that may be carried on the hands of health care workers. Gloves protect caregivers from contamination when contacting blood, body fluids, secretions, excretions, mucous membranes, and nonintact skin of patients and when handling or touching visibly or potentially contaminated patient care equipment and environmental surfaces.14

Respiratory Protection

Respiratory protection (use of NIOSH-approved N-95 or higher level respirator) is intended for diseases (e.g., M. tuberculosis, SARS, smallpox) that could be transmitted through the airborne route.6 The term respiratory protection has a regulatory context that includes components of a program required by OSHA to protect workers: (1) medical clearance to wear a respirator, (2) provision and use of appropriate NIOSH-approved fit-tested respirators, and (3) education in respirator use. Information on types of respirators can be found at www.cdc.gov/niosh/npptl/respirators/respsars.html.

Gowns, Aprons, and Protective Apparel

Isolation gowns and other apparel (aprons, leg coverings, boots, or shoe covers) also provide barrier protection and can prevent the contamination of clothing and exposed body areas from blood and body fluid contact and transmissible pathogens (e.g., respiratory syncytial virus and Clostridium difficile). Selection of protective apparel is dictated by the nature of the interaction of the health care worker with the patient, including anticipated degree of body contact with infectious material.6 In most instances, gowns are worn only if contact with blood and body fluid is likely. Clinical coats and jackets worn over clothing are not considered protective apparel. Isolation gowns should always be donned with gloves and other protective equipment as indicated. As with gloves and masks, a gown should be worn only once and then discarded. In most situations, aseptically clean, freshly laundered, or disposable gowns are satisfactory.

The emergence of SARS and the ongoing concerns for pandemic infection have led to a strategy of preventing transmission of respiratory infections at the first point of contact within a health care setting (e.g., physician’s office) termed respiratory hygiene/cough etiquette that is intended to be incorporated into infection control practices as one component of standard precautions.6 The elements of respiratory hygiene/cough etiquette include (1) education of health care personnel, patients, and visitors; (2) posted signs in language appropriate to the population served with instructions for patients and accompanying family members or friends; (3) source control measures (covering the mouth and nose with a tissue when coughing or placing a surgical mask on a coughing person when possible); (4) hand hygiene after contact with respiratory secretions; and (5) spatial separation (≥3 feet from persons with respiratory infections in common waiting areas).

Transmission-Based Precautions

Transmission-based precautions are for patients who are known or suspected to be infected with pathogens that require additional control measures to prevent transmission. There are three categories of transmission-based precautions: contact precautions, droplet precautions, and airborne infection isolation. Whether used singularly or in combination, these precautions are always used in addition to standard precautions.6

Contact precautions are intended to reduce the risk of transmission by direct or indirect contact with the patient or the patient’s environment. Contact precautions intend for spatial separation of infected or colonized patients (≥3 feet between beds), and health care personnel and visitors wear gowns and gloves for all interactions that may involve contact with the patient or the patient’s environment. Contact precautions are most commonly employed to decrease the spread of multidrug-resistant organisms such as C. difficile. Contact precautions are described in Box 4-4.

Droplet precautions are used to prevent a form of contact transmission that occurs when droplets are propelled short distances (≤3 feet through the air). Droplets are often generated with coughing, sneezing, suctioning, bronchoscopy, and cough induction. Health care personnel and visitors should don a mask during all interactions that may involve contact with such patients. Droplet precautions are employed for patients with presumed or confirmed infection with organisms known to be transmitted by respiratory droplets such as influenza. Droplet precautions are described in Box 4-5. Precautions for use when performing cough-inducing and aerosol-producing procedures are described in Box 4-6.

Airborne Infection Isolation

AI refers to isolation techniques intended to reduce the risk of selected infectious agents transmitted by “small droplets” of aerosol particles (e.g., M. tuberculosis).6 Persons who enter an AI room must wear respiratory protection (an NIOSH-approved N-95 or higher respirator). Patients should be placed in a single-patient AI room that is equipped with special air handling and ventilation capacity that meets the American Institute of Architects/Facility Guidelines Institute standards (monitored negative pressure relative to surrounding area, two air exchanges per hour, and air exhausted directly to the outside or recirculated through high-efficiency particulate air/aerosol [HEPA] filtration). In settings where AI cannot be implemented because of limited resources, one should implement physical separation, mask patients, and provide respiratory protection for health care personnel to reduce the likelihood of airborne transmission. Box 4-7 describes airborne precautions that should be used in addition to standard precautions.

Protective Environment

A specialized engineering approach to protect highly immunocompromised patients is a protective environment. A protective environment is used for patients with allogeneic hematologic stem cell transplants to minimize fungal spore counts in the air.15 The rationale for such controls has been studies showing outbreaks of aspergillosis associated with construction. Air quality for patients with hematologic stem cell transplants is improved through a combination of environmental controls that include (1) HEPA filtration of incoming air, (2) directed room airflow, (3) positive room air pressure relative to the corridor, (4) well-sealed rooms to prevent infiltration of outside air, (5) ventilation to provide 12 or more air changes per hour, (6) strategies to reduce dust, and (7) prohibition of dried and fresh flowers and potted plants in rooms.

Transport of Infected Patients

By limiting the transport of patients with contagious disease, the risk of cross infection can be reduced. However, infected patients sometimes do need to be transported, and when that occurs, the patient needs to wear appropriate barrier protection (mask, gown, impervious dressings) consistent with the route and risk for transmission.6 Health care personnel receiving the patient need to be notified of the patient’s impending arrival and what infection control measures are required.

Disinfection and Sterilization

Medical instruments are used in tens of millions of procedures in the United States every year. When properly performed, cleaning, disinfection, and sterilization procedures can reduce the risk of infection associated with the use of invasive and noninvasive medical instruments. Although a detailed review of disinfection and sterilization is beyond the scope of this chapter, overall principles are discussed, particularly as they pertain to the use of bronchoscopes. The interested reader is referred to detailed guidance available from the CDC.16 Table 4-2 lists definitions of the steps involved in equipment reprocessing.

TABLE 4-2

Equipment Processing Definitions

| Term | Definition |

| Cleaning | Removal of all foreign material (e.g., soil, organic material) from objects |

| Disinfection (general term) | Inactivation of most pathogenic organisms, excluding spores |

| Disinfection, low-level | Inactivation of most bacteria, some viruses, and fungi, without destruction of resistant microorganisms such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis or bacterial spores |

| Disinfection, intermediate-level | Inactivation of all vegetative bacteria, most viruses, most fungi, and M. tuberculosis, without destruction of bacterial spores |

| Disinfection, high-level | Inactivation of all microorganisms except bacterial spores (with sufficient exposure times, spores may also be destroyed) |

| Sterilization | Complete destruction of all forms of microbial life |

Bronchoscopes routinely become contaminated with high levels of organisms during a procedure because of the body cavities in which they are used. The benefits of these medical devices are numerous; however, proper reprocessing is crucial because numerous outbreaks and pseudooutbreaks owing to improper procedures have been described. Individuals responsible for bronchoscope reprocessing should receive initial and annual training, and their competency should be ensured. The five key components to bronchoscope reprocessing are cleaning, disinfecting, rinsing, drying, and storage (Box 4-8).16 Automated bronchoscope reprocessors (ABRs) offer many advantages over manual disinfection because they automate several steps. Regardless of whether disinfection is done manually or with an ABR, personnel responsible for this task need to ensure reprocessing is done per device manufacturer and reprocessor guidelines with products approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Spaulding Approach to Disinfection and Sterilization of Patient Care Equipment

In 1968, Spaulding published his approach to disinfection and sterilization, which was based on the degree of risk of infection involved in the use of the item in patient care.17 The three categories he described were critical, semicritical, and noncritical (Table 4-3). Critical items are categorized based on the high risk of infection if such an item is contaminated with pathogens, including bacterial spores (e.g., items that enter sterile tissue or the vascular system). Critical devices enter normally sterile tissues. Most of these items should be purchased sterile or be sterilized, by steam sterilization if possible. Semicritical items come into contact with mucous membranes or nonintact skin; this includes most respiratory equipment. These items should be free of all microorganisms before use (bacterial spores may be present). Semicritical items require at least high-level disinfection using chemical disinfectants. Noncritical items come into contact with intact skin (an effective barrier to most microbes) but not mucous membranes. Most noncritical reusable devices may be decontaminated where they are used (e.g., bedpans, patient bed rails).

TABLE 4-3

Processing of Medical Equipment According to Infection Risk Categories

| Category | Description | Examples | Processing |

| Critical | Devices introduced into the bloodstream or other parts of the body | Surgical devices | Sterilization |

| Intravascular catheters | |||

| Implants | |||

| Heart-lung bypass components | |||

| Dialysis components | |||

| Bronchoscope forceps/brushes | |||

| Semicritical | Devices that directly or indirectly contact mucous membranes | Bronchoscopes Oral, nasal, and tracheal airways |

High-level disinfection |

| Ventilator circuits/humidifiers | |||

| PFT mouthpieces and tubing | |||

| Nebulizers and their reservoirs | |||

| Resuscitation bags | |||

| Laryngoscope blades/stylets | |||

| Pressure, gas, or temperature probes | |||

| Noncritical | Devices that touch only intact skin or do not contact patient | Face masks | Detergent washing |

| Blood pressure cuffs | Low- to intermediate-level disinfection | ||

| Ventilators |

PFT, Pulmonary function testing.

Modified from Chatburn RL, Kallstrom TJ, Bajasouzian S: A comparison of acetic acid with a quartinary ammonium compound for disinfection of hand-held nebulizers. Resp Care 34:98-109, 1989.

Cleaning

Medical equipment must be cleaned and maintained according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Noncritical items, such as commodes, intravenous pumps, and ventilator surfaces, must be thoroughly cleaned and disinfected before use with another patient. Cleaning is the first step in all equipment processing. Cleaning involves removing dirt and organic material from equipment, usually by washing (see Table 4-3).16 Failure to clean equipment properly can render all subsequent processing efforts ineffective. Cleaning should occur in a designated facility with separate dirty and clean areas. Before being cleaned, the equipment should be disassembled and examined for worn parts. Complete disassembly helps ensure good exposure to the cleaning agent. After disassembly, the parts should be placed in a clean basin filled with hot water and soap, detergent, or enzymatic cleaners.

Disinfection

Disinfection describes a process that destroys the vegetative form of all pathogenic organisms on an inanimate object except bacterial spores. By definition, disinfection differs from sterilization by its lack of sporicidal activity.16 However, a few disinfectants kill spores with prolonged exposure times (hours) and are called chemical sterilants. Disinfection can involve either physical or chemical methods. The most common physical method of disinfection is pasteurization. Many chemical methods are used to disinfect respiratory care equipment.

Chemical Disinfection

Chemical disinfection involves the application of chemical solutions to contaminated surfaces or equipment. For disinfection, the equipment is immersed in the solution. After a set “contact” time, the equipment is removed, rinsed in sterile water (to remove toxic residues), and dried. Equipment must be handled aseptically, with sterile gloves and towels, to prevent recontamination during subsequent reassembly and packaging. The FDA provides a list of cleared chemical disinfectants that can be used for high-level disinfection of medical devices. Cleared agents include agents that are 2.4% or greater glutaraldehyde, 0.55% ortho-phthaladehyde (OPA), 0.95% glutaraldehyde with 1.64% phenolphenate, 7.35% hydrogen peroxide with 0.23% peracetic acid, 1.0% hydrogen peroxide with 0.08% peracetic acid, and 7.5% hydrogen peroxide.16 The choice of agent is dictated by device and in many cases recommendations of the ABR manufacturer.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency groups disinfectants based on whether the product label claims “limited,” “general,” or “hospital” disinfection.16 Numerous disinfectants are used alone or in combination in the health care setting, including alcohol, chlorine and chlorine products, glutaraldehyde, iodophors, phenolics, quaternary ammonium compounds, peracetic acid, and hydrogen peroxide. In most cases, a given product is designed for a specific purpose and should be used in a certain manner; the label should be read carefully. Table 4-4, excerpted from the CDC guideline for sterilization and disinfection, summarizes common chemical disinfectants and their activity against various pathogens.16 Health care facilities should select disinfectant agents that best meet their overall needs. Recommendations for the amount, dilution, and contact time of disinfectants should be followed. A comprehensive overview of disinfectants in the hospital can be found in the updated CDC guidelines for disinfection and sterilization in health care facilities.16

TABLE 4-4

| HP (7.5%) | PA (0.2%) | Glut (≥2.0%) | OPA (0.55%) | HP/PA (7.35%/0.23%) | |

| HLD claim | 30 min at 20° C | NA | 20-90 min at 20°-25° C | 12 min at 20° C, 5 min at 25° C in AER | 15 min at 20° C |

| Sterilization claim | 6 hr at 20° C | 12 min at 50°-56° C | 10 hr at 20°-25° C | None | 3 hr at 20° C |

| Activation | No | No | Yes (alkaline glut) | No | No |

| Reuse lifea | 21 days | Single use | 14-30 days | 14 days | 14 days |

| Shelf life stabilityb | 2 yr | 6 mo | 2 yr | 2 yr | 2 yr |

| Disposable restrictions | None | None | Localc | Localc | None |

| Materials compatibility | Good | Good | Excellent | Excellent | No data |

| Monitor MECd | Yes (6%) | No | Yes (≥1.5%) | Yes (0.3% OPA) | No |

| Safety | Serious eye damage (safety glasses) | Serious eye and skin damage (conc soln)e | Respiratory | Eye irritant, stains skin | Eye damage |

| Processing | Manual or automated | Automated | Manual or automated | Manual or automated | Manual |

| Organic material resistance | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| OSHA exposure limit | 1 ppm TWA | None | Nonef | None | HP-1 ppm TWA |

| Cost profile (per cycle)g | + (manual), ++ (automated) | ++++ (automated) | + (manual), ++ (automated) | ++ (manual) | ++ (manual) |

aNumber of days a product can be reused as determined by reuse protocol.

bTime a product can remain in storage (unused).

cNo U.S. Environmental Protection Agency regulations, but some states and local authorities have additional restrictions.

dMinimum effective concentration (MEC) is the lowest concentration of active ingredients at which the product is still effective.

eConc soln, concentrated solution.

fThe ceiling limit recommended by the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists is 0.05 ppm.

gPer cycle cost profile considers cost of the processing solution (suggested list price to health care facilities in August 2001) and assumes maximum use life (e.g., 21 days for hydrogen peroxide, 14 days for glutaraldehyde), five reprocessing cycles per day, 1-gallon basin for manual processing, and 4-gallon tank for automated processing. + = least expensive; ++++ = most expensive.

Data from Rutala WA, Weber DJ and the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Guidelines for sterilization and disinfection in healthcare facilities, Atlanta, GA, 2008, www.edu.gov./hicpac/.pdf/guidelines.

Sterilization

Sterilization destroys all microorganisms on the surface of an article or in a fluid, which prevents transmission of pathogens associated with the use of that item. Both physical and chemical means can achieve sterilization. Physical methods include various forms of heat (steam) and ionizing radiation. Chemical methods of sterilization include low-temperature sterilization technologies such as ethylene oxide (EtO) gas. Table 4-5, excerpted from the CDC guideline for sterilization and disinfection, compares and contrasts the major methods of sterilization.16

TABLE 4-5

Advantages and Disadvantages of Accepted Methods for Equipment Sterilization

| Sterilization Method | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Steam | Nontoxic to patient, staff, environment Cycle easy to control and monitor Rapidly microbial Least affected by organic/inorganic soils among sterilization processes listed Rapid cycle time Penetrates medical packing, device lumens |

Deleterious for heat-sensitive instruments Microsurgical instruments damaged by repeated exposure May leave instruments wet, causing them to rust Potential for burns |

| Hydrogen peroxide gas plasma | Safe for the environment Leaves no toxic residuals Cycle time is 28-75 min (varies with model type) and no aeration necessary Used for heat- and moisture-sensitive items because process temperature <50° C Simple to operate, install (208 V outlet), and monitor Compatible with most medical devices Requires electrical outlet only |

Cellulose (paper), linens, and liquids cannot be processed Sterilization chamber size from 1.8-9.4 ft3 total volume (varies with model type) Some endoscopes or medical devices with long or narrow lumens cannot be processed at this time in the United States (see manufacturer’s recommendations for internal diameter and length restrictions) Requires synthetic packaging (polypropylene wraps, polyolefin pouches) and special container tray Hydrogen peroxide may be toxic at levels >1 ppm TWA |

| 100% EtO | Penetrates packaging materials, device lumens Single-dose cartridge and negative pressure chamber minimizes potential for gas leak and EtO exposure Simple to operate and monitor Compatible with most medical materials |

Requires aeration time to remove EtO residue Sterilization chamber size 4.0-7.9 ft3 total volume (varies with model type) EtO is toxic, a carcinogen, and flammable EtO emission regulation by states but catalytic cell removes 99.9% of EtO and converts it to CO2 and H2O EtO cartridges should be stored in flammable liquid storage cabinet Lengthy cycle/aeration time |

| EtO mixtures: 8.6% EtO/91.4% HCFC; 10% EtO/90% HCFC; 8.5% EtO/91.5% CO2 | Penetrates medical packaging and many plastics Compatible with most medical materials Cycle easy to control and monitor |

Some states (e.g., California, New York, Michigan) require EtO emission reduction of 90%-99.9% CFC (inert gas that eliminates explosive hazard) banned in 1995 Potential hazards to staff and patients Lengthy cycle/alteration time EtO is toxic, a carcinogen, and flammable |

| Peracetic acid | Rapid cycle time (30-45 min) Low temperature (50°-55° C) liquid immersion sterilization Environmentally friendly by-products Sterilant flows through endoscope, which facilitates salt, protein, and microbe removal |

Point-of-use system, no sterile storage Biologic indicator may be unsuitable for routine monitoring Used for immersible instruments only Some material incompatibility (e.g., aluminum anodized coating becomes dull) One scope or a small number of instruments processed in a cycle Potential for serious eye and skin damage (concentrated solution) with contact |

CFC, Chlorofluorocarbon; HCFC, hydrochlorofluorocarbon.

Data from Rutala WA, Weber DJ and the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Guidelines for sterilization and disinfection in healthcare facilities, Atlanta, GA, 2008, www.edu.gov./hicpac/.pdf/guidelines.

Medical devices that have contact with sterile body tissues or fluids are crucial items and should be sterile before use. If the object is heat resistant, steam sterilization is usually recommended. However, increases in the use of medical devices that are heat and moisture sensitive have necessitated the development of low-temperature sterilization technology. These include, but are not limited to, EtO, hydrogen peroxide gas plasma, and peracetic acid. A review of the commonly used sterilization technologies with a summary of advantages and disadvantages can be found in the updated CDC guidelines for disinfection and sterilization in health care facilities.16 Following is an overview of a few of these technologies.

Flash Sterilization

Flash “steam sterilization” is a modification of conventional steam sterilization in which the item is placed in an open tray or a specially designed container to allow for rapid penetration of steam.16 It is considered an acceptable practice for processing cleaned patient care items that cannot be packaged, sterilized, and stored before use. Its use only for reasons of convenience (e.g., to save time) should be discouraged.

Low-Temperature Sterilization Technologies

Low-temperature (<60° C) sterilants are needed for sterilizing temperature-sensitive and moisture-sensitive medical devices and equipment. Low-temperature sterilant technology includes EtO, hydrochlorofluorocarbon, hydrogen peroxide gas plasma, and peracetic acid.16 We review the most commonly used process—EtO.

EtO is a colorless, toxic gas and potent sterilizing agent. Because it is active at ambient temperatures and is harmless to rubber and plastics, EtO is a good sterilant for items that cannot be autoclaved. Similar to steam, EtO penetrates most packaging materials, permitting prewrapping. Were it not for its many hazards, EtO would be the ideal sterilant.18 Acute exposure to EtO gas can cause airway inflammation, nausea, diarrhea, headache, dizziness, and convulsions. Chronic exposure to the gas is associated with respiratory infections, anemia, and altered behavior. Residual EtO left on processed equipment can cause tissue inflammation and hemolysis. When combined with water, EtO forms ethylene glycol, which also can irritate tissues. Other potential problems include carcinogenic, mutagenic, and teratogenic effects. EtO concentrations greater than 3% are explosive.

Equipment Handling Procedures

Maintenance of In-Use Equipment

Nebulizers

Small volume medication nebulizers (SVNs) can also produce bacterial aerosols. SVNs have been associated with nosocomial pneumonia, including Legionnaires’ disease, resulting from either contaminated medications or contaminated tap water used to rinse the reservoir. Procedures designed to prevent nebulizers from spreading pathogens are presented in Box 4-9.

Ventilators and Ventilator Circuits

One way to address this problem is by reducing or eliminating circuit condensation. This reduction or elimination is easily achieved using heated wire circuits or a heat-and-moisture exchanger (HME). Evidence suggests that to prevent bacterial colonization, even if the HME remains free of secretions, the maximal duration that it may be used is 96 hours (4 days).19

Based on current knowledge, both the CDC and the American Association for Respiratory Care (AARC) developed guidelines addressing ventilator-associated infection control. Box 4-10 provides general procedures for minimizing nosocomial infection associated with ventilator use. Mechanical ventilation exposes the patient to the risk of VAP, and the frequency of circuit changes and the relationship to VAP have been investigated.20,21 Current guidelines suggest that ventilator circuits should not be changed routinely for infection control purposes; however, they should be changed when visibly soiled or malfunctioning.

Bag-Mask Devices

Bag-mask devices are a source for colonizing both the airways of intubated patients and the hands of medical personnel.22 Nondisposable bag-mask devices should be sterilized or high-level disinfected between patients. In addition, the exterior surface of any bag-mask device should be cleaned of visible debris and disinfected at least once a day.

Suction Systems

Tracheal suctioning increases the risk of infection. Proper handwashing and gloving help minimize this risk. Although much has been made of the infection control advantages of ensheathed suction systems over open tracheal suction systems, evidence shows neither system to be clearly superior.4 To minimize the risk of cross contamination during suctioning with an open system, a fresh, sterile single-use catheter should be used on each patient. In addition, only sterile fluid should be used to remove secretions from the catheter. Last, both the suction collection tubing and collection canister should be changed between patients except in short-term care units, where only the collection tubing needs to be changed.

Oxygen Therapy Apparatus

Oxygen therapy devices pose much less risk than other in-use equipment but are still a potential infection hazard. In-use nondisposable oxygen humidifiers have a contamination rate of 33%. Conversely, prefilled, sterile disposable humidifiers present a negligible infection risk.23 On the basis of this knowledge, procedures that can help prevent oxygen therapy apparatus from spreading pathogens are outlined in Box 4-11.

Pulmonary Function Equipment

The inner parts of pulmonary function testing equipment are not a major source for spread of infection. However, contamination of external tubing, connectors, rebreathing valves, and mouthpieces can occur during testing. These components should be cleaned and subjected to high-level disinfection or sterilization between patients.4 The common practice of using HEPA filters to isolate the spirometer from the patient makes sense logically but has yet to be proven either effective or necessary in preventing nosocomial infection.

Other Respiratory Care Devices

Use of other respiratory care equipment, including oxygen analyzers, the hand-held bedside respirometer, and circuit probes, has been linked with hospital outbreaks of gram-negative bacterial infections.4 The most likely transmission route is direct patient-to-patient contact via either the device itself or the contaminated hands of caregivers. The best way to control this problem is with proper handwashing and sterilization or high-level disinfection of the devices between patients.

Processing Reusable Equipment

Respiratory Care Equipment

Several factors must be considered in selecting a processing method for reusable respiratory care equipment (Box 4-12). When a device’s risk category is known, its composition must be matched to the resources available for hospital disinfection and sterilization. In this manner, each reusable device undergoes the most effective and least costly processing approach available.

HAIs associated with bronchoscopes have been most commonly reported with M. tuberculosis, nontuberculosis mycobacteria, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.22 The most common reasons for transmission include failure to adhere to recommended cleaning and disinfection procedures, failure of automated endoscope reprocessors, and flaws in design. Flexible endoscopes are particularly difficult to disinfect, and meticulous cleaning must precede any sterilization or high-level disinfection process.

Disposable Equipment

Cost savings notwithstanding, many quality issues persist. Although disposable devices generally perform well, poor quality control remains a problem.23 Respiratory care managers need to evaluate carefully disposable devices being considered for bulk purchase before actual clinical use.24 To ensure reliability, this evaluation should include physical testing of multiple units of each model being assessed. Finally, bedside clinicians need to inspect carefully and confirm the operation of any disposable device before use.

Reusing high-cost, high-volume disposable equipment saves hospitals money. The practice of reusing devices labeled by the manufacturer for “single-use only” raises significant safety concerns and issues of negligence.25 The CDC recommends that single-use devices be considered for reuse only if there is good evidence that reprocessing poses no threat to the patient and does not alter the function of the device.4 Individuals responsible for reusing disposable equipment bear a significant burden of proof. Without such proof, users of reprocessed single-use devices may be transferring legal liability for the safe performance of the product from the manufacturer to themselves or their employer.26

Using Needles and Syringes

Needlestick injuries are a growing area of concern among health care personnel because accidental skin puncture with a contaminated sharp can transmit blood-borne pathogens such as hepatitis C and HIV to the health care worker.2 All health care workers should exercise extreme caution when handling any sharp instruments, including needles and syringes.

Surveillance for Hospital-Acquired Infections

Surveillance is an ongoing process of monitoring patients and health care personnel for acquisition of infection or colonization of pathogens, or both. It is one of the five key recommended components of an infection prevention program; the others are investigation, prevention, control, and reporting.2 Surveillance is a tool to provide HAI data on patients to provide outcome measurements either to ensure that there is no ongoing problem or to detect problems and intervene to prevent transmission of pathogens in the health care environment.

Generally, an infection prevention committee establishes surveillance policies, and an infection control nurse or epidemiologist administers them. The surveillance program may be centralized or decentralized (to the various service departments). The following principles should be a part of any infection prevention surveillance program2: (1) use of standard definitions for HAIs, (2) use of microbiology-based data (when available) including resistance patterns for pathogens of significance (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus), (3) establishment of risk stratification for infection risk when available (e.g., ventilator days, device days), (4) monitoring of results prospectively and identifying trends that indicate unusual rates of infection or transmission within the facility, and (5) provision of feedback to stakeholders within the institution (e.g., surgical site infection rates reported back to individual surgeons). It is also common for infection prevention programs to oversee hand hygiene and standard precautions adherence observations. Increasingly, data on adherence to infection prevention processes such as the VAP bundle and patient and health care influenza vaccination rates are available.