chapter 4 Principles of herbal medicine

INTRODUCTION

Throughout human history, people have relied on nature to provide their basic needs. Plants in particular have been a source of clothing, shelter, food, flavours and fragrances. Importantly, plants have also formed the basis of numerous traditional medicinal systems around the world, including Ayurveda (Indian), traditional Chinese medicine, Unani (Persian) and European. Herbs used within these healing systems have given rise to many of the drugs used in contemporary Western medical practice and continue to be a source of therapeutic medicines for many people (see Table 4.1). While many of the time-honoured attributes of herbal medicines have been confirmed with scientific testing and have proved to be significant and still extremely useful, others have proved to be erroneous.

TABLE 4.1 Examples of pharmaceutical drugs derived from plants

| Drug | Herb |

|---|---|

| Aspirin | Meadowsweet |

| Atropine | Atropa belladonna |

| Caffeine | Camellia sinensis |

| Cocaine | Erythroxylum coca |

| Colchicine | Autumn crocus |

| Digoxin | Digitalis purpurea |

| Ephedrine | Ephedra sinica |

| Morphine | Papaver somniferum |

| Pilocarpine | Pilocarpus species |

| Paclitaxel | Pacific yew |

| Theophylline | Theobroma cacao and others |

| Vincristine | Madagascar periwinkle |

Today, herbal medicine (or phytomedicine) can be broadly defined as both the science and the art of using botanical medicines to prevent and treat illness, and the study and investigation of these medicines.1 The term phytotherapy is used to describe the therapeutic application of herbal medicines, and was first coined by the French physician Henri Leclerc (1870–1955), who published numerous essays on the use of medicinal plants.2 Herbal medicine has come a long way since the days of ancient ‘herbalism’, especially in regards to growing and manufacturing techniques, quality control and the steady accumulation of scientific evidence to elucidate mechanisms of action, efficacy and safety.

HERBS, DRUGS AND PHYTOCHEMICALS

Botanical medicines are chemically complex substances with many different constituents. For example, a herbal medicine may contain mucilage, essential oils, macro- and micronutrients such as fats and carbohydrates, proteins and enzymes. They also contain many other phytochemicals such as secondary metabolites, which form the plant’s natural defence against herbivores, pathogens, insect attack and microbial decomposition, or are produced in response to injury or infection or used for signalling and growth regulation. Secondary metabolites are important in herbal medicine as they are often the constituents responsible for producing the herb’s main therapeutic effects. Examples of secondary metabolites are tannins, isoflavones, saponins, flavonoids, glycosides, coumarins, bitters and phyto-oestrogens.3

It can be tempting to adopt a reductionist approach and attribute a herb’s activity to one particular active constituent; however, this is rarely the case as the herb’s pharmacological activity depends on the composition of the whole extract. Other constituents, even those with no direct physiological effect, may influence the uptake, distribution, metabolism and excretion of other components. Furthermore, this background matrix may affect the solubility, stability and bioavailability of any given compound.

CLINICAL RELEVANCE

St John’s wort has been used as a treatment for neuralgic conditions since the time of Ancient Greece and as a treatment for psychiatric disorders since the time of Paracelsus.4 It was traditionally used as a tea, an aqueous extract, and it is included in the national pharmacopoeias of many European countries. In 2005 a Cochrane systematic review of 37 clinical trials, including 26 comparisons with placebos and 14 comparisons with synthetic antidepressant drugs, confirmed its effectiveness for mild to moderate depression, thereby providing strong support for one of its main traditional uses.5

St John’s wort contains several active constituents, but it is generally accepted that the hyperforin and hypericin constituents are chiefly responsible for its antidepressant and anxiolytic effects.1 In the past 5 years, researchers have identified that an extract devoid of both hypericin and hyperforin still has antidepressant effects, suggesting that other constituents in the extract are also pharmacologically active.6 Current research has identified several new active constituents, but others remain elusive. In addition, several other components previously considered devoid of activity have been found to alter the pharmacokinetics of key active constituents. For example, procyanidin B2 and hyperoside increase the oral bioavailability of hypericin by 58% and 34% respectively.7 Therefore, current scientific knowledge has demonstrated that the total extract has to be considered the active substance, and that the herb’s pharmacological effects cannot be described as simply due to one or two active constituents.

In the late 1990s, the extraction method used by some commercial producers was modified, resulting in higher hyperforin concentrations than previously seen.8 A St John’s wort extract known as LI 160 is one of these higher-hyperforin types. Since this time, numerous reports and studies have identified pharmacokinetic drug interactions with St John’s wort based on its ability to induce cytochromes and P-glycoprotein, and the hyperforin constituent has been identified as the key constituent responsible for these induction effects.1 Meanwhile, studies with low-hyperforin St John’s wort preparations, such as Ze 117, have not found evidence of the same interactions.8 Unfortunately, the distinction between preparations is not well appreciated in the literature and many reference texts fail to mention this important point.

QUALITY CONTROL AND PRODUCT REGULATION

In Australia there is an international best-practice, risk-based regulatory system for both complementary and pharmaceutical medicines.1 The Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care delegates responsibility for the regulation of complementary medicines to the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA), which has an office dedicated to this role (Office of Complementary Medicines). The TGA is responsible for product quality, safety, claims, registration, post-marketing monitoring and setting standards for manufacturing. All herbal products manufactured commercially in Australia must be produced according to the code of Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP). In 1997, the Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister for Health and Family Services established a new ministerial advisory committee, the Complementary Medicines Evaluation Committee (CMEC), which advises the TGA and government on the regulation of complementary medicines.

In 2004, Health Canada officially added a new term to the global list of synonyms for dietary supplements: natural health products (NHP), with the release of its Natural Health Products Regulations (the NHP regulations). The regulations are applicable to the sale, manufacture, packaging, labelling, importation, distribution and storage of NHP, and are administered by the recently formed Natural Health Products Directorate (NHPD) within Health Canada. Herbal medicines fall into the NHP category. One of the main components of the NHP regulations is product licensing. Under the new regulations, all NHP are required to undergo pre-market review to obtain a product licence and a corresponding Natural Product Number (NPN). In addition to providing data on the safety, efficacy and quality of NHP ingredients, each manufacturer applying for a product licence must provide information regarding the site of manufacture, packaging, labelling, distribution or importation, with corresponding site licence (SL) numbers, acquired through the submission of a site licence application (SLA). A site licence provides some assurance that current good manufacturing practice is being undertaken.9

In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has treated dietary supplements, such as herbal medicines, as foods since 1994 with the enactment of the Dietary Supplement Health Education Act (DSHEA). The DSHEA resulted from a grassroots campaign protesting against the ongoing efforts of the FDA to regulate dietary supplements as drugs, not foods. The DSHEA led to the existence of two sets of regulatory standards, one for foods (including dietary supplements) and the other for drugs (medicines). It also transferred to manufacturers the responsibility for ensuring product safety and the requirement that any therapeutic claims be substantiated by adequate evidence.10

Regulation of herbal products differs substantially between Australia, Canada and the United States in that, under the DSHEA, a manufacturer is not required to obtain approval from the FDA prior to marketing its product, although other provisions must be satisfied to ensure a reasonable expectation of safety. Because the FDA has no regulatory control over what products are on the market, it can only remove a dietary supplement from the market if it can prove that the product has violated the regulations governing product safety, information and labelling, or claims after the product reaches the market. To withdraw a product, the FDA must also prove that the product places the consumer at ‘significant or unreasonable risk’.10

Unlike Australia, Canada and the United States, in several European countries botanical medicines have always been part of mainstream medicine and therefore have been included in the regulations of each country from the beginning. Herbal medicines fall within the scope of the European Directive 2001/83/CE, but there is still little harmonisation between countries in regards to regulation.11 In some European Union (EU) countries, herbal products are sold as foods, or incorporated in functional/fortified foods or as food supplements, meaning that no medicinal claims are made, whereas in other EU countries these preparations are registered by full or simplified registration procedures. In some countries, the medicinal product status is automatically linked to pharmacy-only status.12 For example, in Germany, almost all botanical medicines are considered medicinal agents and require medical authorisation. In the United Kingdom, some herbal medicines require registration under the Traditional Herbal Medicinal Products Directive or full medicines authorisation, whereas others considered not medicinal by function are permitted in supplements and foods.12

The classification of Ginkgo biloba in different countries provides a further example: in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands, Ginkgo biloba can be sold as a food supplement; in Germany and France it is a registered OTC medicine; in Ireland it is available as ‘prescription only’.12

HERBAL SAFETY AND ADVERSE REACTIONS

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines an adverse drug reaction (ADR) as a ‘response to a medicine which is noxious and unintended that occurs at doses normally used in humans’. When two medicines interact in a way that produces an unwanted effect, this is also referred to as an adverse drug reaction. Factors associated with an increased likelihood of developing an ADR to a drug or herbal medicine include: advanced age, polypharmacy, dementia or confusion, history of atopic disease, prolonged and frequent therapy, and compromised hepatic and/or renal function.1

Herbal adverse effects can be categorised in a similar way to pharmaceutical medicines and are mainly type A or type B reactions. Type A reactions are anticipated and predictable reactions and tend to be dose related. A herbal example is halitosis and dyspepsia caused by garlic, and a pharmaceutical example is bleeding caused by warfarin or hepatotoxicity from paracetamol. Type B reactions are idiosyncratic and uncommon, difficult to predict and not dose related. They tend to have higher morbidity and mortality than Type A reactions and are often immunologically mediated.13 A herbal example is hepatotoxicity caused by black cohosh, and a pharmaceutical example is interstitial nephritis with the use of NSAIDs.

EVIDENCE AND SCIENTIFIC VALIDATION

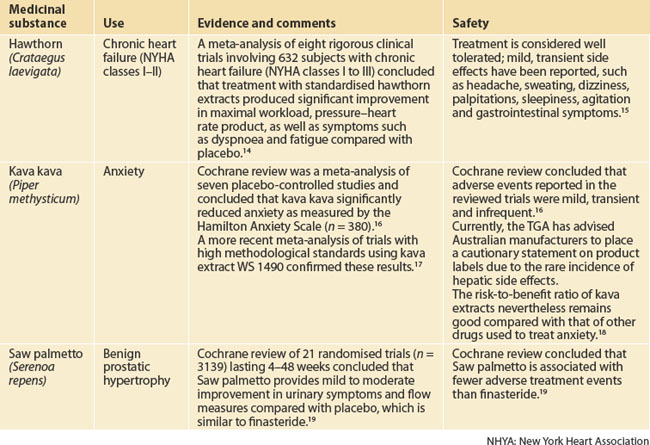

Over the past 40 years, scientific evidence has extended the traditional evidence base and enabled a better understanding of phytomedicines to emerge. Research has been conducted to isolate and identify key active constituents in botanical medicines and their mechanisms of action. This field of enquiry is appropriately termed phytochemistry. Efficacy and safety studies have also been conducted and there is now good evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analyses (including Cochrane reviews) of randomised controlled trials for the efficacy of certain standardised herbal extracts. Three examples are provided in Table 4.2.

Until recently, most phytomedicine research was conducted in Europe and Asia, where there is a rich tradition of use. Research in this area in the United States remained stagnant until the 1990s, when rapid growth and public interest in phytotherapy motivated the government to start dedicating more funds to research. Interestingly, by 1997, the Office of Alternative Medicine in the United States was renamed the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM), indicating greater acceptance of therapeutic approaches such as phytotherapy.20 Notwithstanding these efforts, a relative lack of resources, infrastructure, government funding and financial incentives for investment in non-patentable medicines research has impeded herbal research worldwide.

Phytomedicine research in Australia continues to struggle due to a severe lack of funds despite its enormous public popularity. In 2007 the Australian Government earmarked $5 million for complementary medicine research via a National Health and Medical Research Council special call. Over 140 submissions were made, indicating enormous interest among researchers. In the same year, the National Institute of Complementary Medicine (NICM) was created using seed money provided by the Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing together with the New South Wales Office for Science and Medical Research (OSMR) (www.nicm.org.au). The aim of the NICM was to build the capacity of complementary medicine research across Australia, effectively connecting complementary medicine researchers and professionals with the broader research community, industry and other stakeholders, to provide strategic focus and foster excellence in research. However, funding was suspended in 2009.

THE PRACTICE OF WESTERN HERBAL MEDICINE

Western herbal medicine is the main form of phytotherapy practised today by herbalists in the United States, Europe, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. It is built on European and Greco-Roman healthcare traditions and can be traced back to prominent physicians such as Dioscorides, Hippocrates and Galen. Over the past century, with greater cross-cultural exchange, the European influence in Western herbal medicine practice has lessened and there has been some adoption of herbal medicines and practices from other continents. The popular immune-modulating herb Echinacea and the menopausal treatment black cohosh are two examples of this cross-cultural exchange, having emanated from the North American Indians. With today’s increased ease of global communication and transport, the continued exchange of ideas and medicines with other cultures keeps broadening the practice of Western phytotherapy. It is now commonplace to find herbs such as Korean ginseng from Asia, Echinacea from North America, tea tree from Australia, chamomile from Germany and Andrographis from India sitting together in a herbalist’s dispensary.

PHILOSOPHY AND THE HERBALIST’S APPROACH

Medical herbalists are trained in basic sciences such as anatomy, physiology and biochemistry, basic pharmacology and clinical diagnosis in order to enable a comprehensive history to be taken, identifying symptoms and underlying disease. According to an Australian workforce survey, 85% of naturopaths and Western herbalists also hold first aid certification and approximately 90% regularly attend continuing education seminars.21 The same survey identified that nearly 40% of practitioners use Western diagnostic tests such as pathology and radiology to guide their clinical practice and nearly two-thirds perform physical examinations. In addition, most use traditional naturopathic diagnostic assessments.

Source: NHAA22

In Australia, the knowledge and practice of herbal medicine has been preserved and nurtured mainly by Western herbalists. In fact, the National Herbalists Association of Australia (NHAA) has represented medical herbalists since 1920. Today, the association is widely recognised as setting industry standards for education in medical herbalism. It has a constitution and a code of ethics, liaises with private health funds to ensure reimbursement of patient fees for its accredited practitioners and continues to advocate professional registration by government bodies. Clinicians are encouraged to check whether herbal practitioners to whom they refer have undergone accredited courses. Further information can be found by contacting the association or accessing the website (www.nhaa.org.au).

HOW PHYTOTHERAPY INTEGRATES WITH GENERAL PRACTICE

Surveys conducted in the Western world consistently report on the popularity of herbal medicines.23–26 This means that general practitioners are coming into contact with an increasing number of patients taking or enquiring about herbs. From this perspective, it is important for clinicians to become familiar with commonly used botanical medicines so they can provide an informed opinion on their safety and efficacy. In addition, the practice of evidence-based medicine demands that treatment decisions be based on the best available evidence. As a consequence, when there is evidence to support the efficacy and safety of a herbal extract, it should also be considered in the treatment plan. As a starting point, Table 4.3 provides a list of 20 over-the-counter (OTC) herbal medicines that GPs should become familiar with. The list is based on popularity and does not include all OTC phytomedicines supported by evidence.

TABLE 4.3 Popular phytomedicines that all GPs should become familiar with

| Common name of herb (Latin name) | Indications/uses |

|---|---|

| Bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus) | Ocular symptoms/disease: preventing and treating diabetic retinopathy, poor night vision, light adaptation and photophobia |

| Black cohosh (Cimicifuga racemosa or Actea racemosa) | Menopausal symptoms, premenstrual syndrome |

| Chaste tree (Vitex agnus-castus) | Premenstrual syndrome, menstrual irregularities |

| Cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon) | Prevention of urinary tract infection |

| Devil’s claw (Harpagophytum procumbens) | Symptomatic relief in osteoarthritis, non-specific lower back pain |

| Echinacea (Echinacea angustifolia and Echinacea purpurea) | Immune modulation, viral upper respiratory tract infections, wound healing (topical) |

| Feverfew (Tanacetum parthenium) | Migraine prophylaxis |

| Ginger (Zingiber officinalis) | Prevention and treatment of motion sickness, morning sickness |

| Ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba) | Dementia, intermittent claudication and poor peripheral circulation |

| Guarana (Paullinia cupana) | Central nervous system stimulant |

| St John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum) | Mild to moderate depression |

| Hawthorn (Crataegus oxycantha) | Heart failure (NYHA classes I–III) |

| Horse chestnut (Aesculus hippocastanum) | Chronic venous insufficiency |

| Kava kava (Piper methysticum) | Anxiety |

| Peppermint (Mentha piperita) | Irritable bowel syndrome, dyspepsia |

| Saw palmetto or serenoa (Sabal serrulata or Serenoa repens) | Symptomatic relief in benign prostatic hypertrophy |

| Slippery elm (Ulmus rubra) | Symptomatic relief of gastritis, dyspepsia, gastric reflux, peptic ulcers, irritable bowel syndrome and Crohn’s disease |

| St Mary’s thistle (Silybum marianum) | Prevent liver injury |

| Tea tree oil (Melaleuca alternifolia) | Topical infections |

| Valerian (Valeriana officinalis) | Anxiety, insomnia |

NHYA: New York Heart Association

TALKING WITH PATIENTS ABOUT HERBAL MEDICINES

Studies indicate that most patients using complementary medicines (including herbal medicines) do not routinely disclose this information to their medical practitioner. In the United States, Eisenberg and colleagues identified that, in 1990, only 39.8% of complementary medicine users disclosed their use to physicians, and in 1997 this figure was 38.5%, suggesting that disclosure had remained poor.25 Many other surveys have had similar findings. One review of patients attending medical clinics identified non-disclosure rates of 23–72%.27 In all 12 studies reviewed, the same three themes were consistently reported as barriers to communication: patient concern about eliciting a negative response from the physician; the patient’s perception that their medical practitioner did not need to know about complementary medicine use because they would be unable to contribute useful information; and lack of clinician enquiry.

Lack of patient disclosure combined with lack of practitioner enquiry results in a ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ culture in which communication barriers are continually reinforced.28 Not only is this situation potentially dangerous, it is also a missed opportunity for practitioners to learn from patients about their reasons for using herbal medicines, whether the treatment has been effective or ineffective, and other details about their healthcare beliefs.

NEXT STEPS

Ideally, you should also notify the following:

PRESCRIBING HERBAL MEDICINES

Patients should be provided with instructions about where they can find the particular product prescribed, how to take and store the medicine, and what they should expect. It is worth discussing a sensible time frame for trialling a herbal medicine so that expectations are realistic and management can be modified if the treatment is not effective. Once again, information about this can be found in clinical trials and good reference texts. For example, herbs such as Ginkgo biloba for mild dementia require a trial of at least 3 months, whereas ginger treatment should alleviate nausea within 1 hour. Box 4.2 provides a summary of these steps.

BOX 4.2 Rational use of herbal medicines: the prescribing steps

BOX 4.1 Reasons to consider using herbal medicines in practice

adapted from Braun & Cohen1

As with good food and good wine, the quality of commercially prepared herbal medicines will vary, as will the price. Learning about different company philosophies and products takes time but will help clinicians to become more confident prescribers. Most importantly, look for opportunities to learn more about herbal medicines from credible sources and become familiar with accredited medical herbalists and pharmacists who have additional herbal medicine training.

Blumenthal M, editor. Herbal medicine: expanded commission E monographs. American Botanical Society Publishers, 2000. The English translation of the official German herbal monographs, with some additional information and commentary.

Blumenthal M. ABC clinical guide to herbs. Austin: Amercian Botanical Council, 2003.

Bone K, Mills S. Principles and practice of phytotherapy. Churchill Livingstone, 2000. Detailed information about phytotherapeutics, herbal philosophy and phytochemistry, with additional monographs.

Braun L, Cohen M. Herbs and natural supplements: an evidence-based guide. 3rd edn. Sydney: Elsevier Australia, 2009. Comprehensive, evidence-based information about 130 complementary medicines popular in Australia and New Zealand, and detailed drug–herb interaction charts.

Gurib-Fakim A. Medicinal plants: traditions of yesterday and drugs of tomorrow. Mol Aspects Med. 2006;27(1):1-93.

Murray M. The healing power of herbs. 2nd edn. California: Prima Press, 1995.

National Herbalists Association of Australia. http://www.nhaa.org.au.

1 Braun L, Cohen MM. Herbs and natural supplements: an evidence-based guide. 3rd edn. Sydney: Elsevier, 2009.

2 Weiss R. Herbal medicine. Stuttgart: Beaconsfield, 1991.

3 Mills S, Bone K. Principles and practice of phytotherapy. Sydney: Elsevier, 2000.

4 Blumenthal M, Goldberg A, Brinckmann J. Herbal medicine: expanded commission E monographs. American Botanical Council, 2000.

5 Linde K, Mulrow CD, Berner M, et al. St John’s wort for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;2:CD000448.

6 Butterweck V, Christoffel V, Nahrstedt A, et al. Step by step removal of hyperforin and hypericin: activity profile of different Hypericum preparations in behavioral models. Life Sci. 2003;73(5):627-639.

7 Butterweck V, Lieflander-Wulf U, Winterhoff H, et al. Plasma levels of hypericin in presence of procyanidin B2 and hyperoside: a pharmacokinetic study in rats. Planta Med. 2003;69(3):189-192.

8 Madabushi R, Frank B, Drewelow B, et al. Hyperforin in St John’s wort drug interactions. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;62(3):225-233.

9 Nestmann ER, Harwood M, Martyres S. An innovative model for regulating supplement products: natural health products in Canada. Toxicology. 2006;221(1):50-58.

10 Brownie S. The development of the US and Australian dietary supplement regulations: what are the implications for product quality? Complement Ther Med. 2005;13(3):191-198.

11 Silano M, De Vincenzi M, De Vincenzi A, et al. The new European legislation on traditional herbal medicines: main features and perspectives. Fitoterapia. 2004;75(2):107-116.

12 Gulati OP, Berry Ottaway P. Legislation relating to nutraceuticals in the European Union with a particular focus on botanical-sourced products. Toxicology. 2006;221(1):75-87.

13 Myers SP, Cheras PA. The other side of the coin: safety of complementary and alternative medicine. Med J Aust. 2004;181(4):222-225.

14 Pittler MH, Schmidt K, Ernst E. Hawthorn extract for treating chronic heart failure: meta-analysis of randomized trials. Am J Med. 2003;114(8):665-674.

15 Rigelsky JM, Sweet BV. Hawthorn: pharmacology and therapeutic uses. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2002;59(5):417-422.

16 Pittler MH, Ernst E. Kava extract for treating anxiety (Cochrane Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;1:CD003383.

17 Witte S, Loew D, Gaus W. Meta-analysis of the efficacy of the acetonic kava-kava extract WS 1490 in patients with non-psychotic anxiety disorders. Phytother Res. 2005;19(3):183-188.

18 Clouatre DL. Kava kava: examining new reports of toxicity. Toxicol Lett. 2004;150(1):85-96.

19 Wilt T, Ishani A, Mac DR. Serenoa repens for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;3:CD001423.

20 Marwick C. Alterations are ahead at the OAM. Office of Alternative Medicine. JAMA. 1998;280(18):1553-1554.

21 Bensoussan A, Myers SP, Wu SM, et al. Naturopathic and Western herbal medicine practice in Australia: a workforce survey. Complement Ther Med. 2004;12(1):17-27.

22 National Herbalists Association of Australia (NHAA). Online. Available www.nhaa.org.au, 3 January 2008.

23 MacLennan AH, Myers SP, Taylor AW. The continuing use of complementary and alternative medicine in South Australia: costs and beliefs in 2004. Med J Aust. 2006;184(1):27-31.

24 Xue C, Zhang L, Lin V, et al. Current usage of complementary and alternative medicine in Australia: a national population-based study. J Altern Complement Med. 2007;13(6):643-650.

25 Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990–1997: results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA. 1998;280(18):1569-1575.

26 Harris P, Rees R. The prevalence of complementary and alternative medicine use among the general population: a systematic review of the literature. Complement Ther Med. 2000;8(2):88-96.

27 Robinson A, McGrail MR. Disclosure of CAM use to medical practitioners: a review of qualitative and quantitative studies. Complement Ther Med. 2004;12(2/3):90-98.

28 Giveon SM, Liberman N, Klang S, et al. A survey of primary care physicians: perceptions of their patients’ use of complementary medicine. Complement Ther Med. 2003;11(4):254-260.