Chapter 487 Principles of Diagnosis

Signs and Symptoms

The symptoms and signs of cancer are variable and nonspecific in pediatric patients. The types of cancer that occur during the first 20 yr of life vary dramatically as a function of age—more so than at any other comparable age range (Chapter 485). Unlike cancers in adults, childhood cancers usually originate from the deeper, visceral structures and from the parenchyma of organs rather than from the epithelial layers that line the ducts and glands of organs and compose the skin. In children, dissemination of disease at diagnosis is common, and presenting symptoms or signs are often caused by systemic involvement. Pain was one of the initial presenting symptoms in more than 50% of children with cancer in one study. Infants and young children cannot express or localize their symptoms well. Another factor is the variability in the physiology and biology of the host related to growth and development during infancy, childhood, and adolescence.

Although there is no clearly established set of warning signs of cancer in young people, the most common cancers in children suggest some guidelines that may be helpful in early recognition of signs and symptoms of cancer (Tables 487-1, 487-2, 487-3). Most of the symptoms and signs are not specific and might represent other possibilities in a differential diagnosis. Nonetheless, these hints encompass the common cancers of childhood and have been very useful in early detection.

| SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS | SIGNIFICANCE | EXAMPLE |

|---|---|---|

| HEMATOLOGIC | ||

| Pallor, anemia | Bone marrow infiltration | Leukemia, neuroblastoma |

| Petechiae, thrombocytopenia | Bone marrow infiltration | Leukemia, neuroblastoma |

| Fever, persistent or recurrent infection, neutropenia | Bone marrow infiltration | Leukemia, neuroblastoma |

| SYSTEMIC | ||

| Bone pain, limp, arthralgia | Primary bone tumor, metastasis to bone | Osteosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, leukemia, neuroblastoma |

| Fever of unknown origin, weight loss, night sweats | Lymphoma | Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma |

| Painless lymphadenopathy | Lymphoma, metastatic solid tumor | Leukemia, Hodgkin lymphoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, Burkitt lymphoma, thyroid carcinoma |

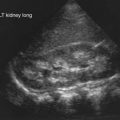

| Abdominal mass | Adrenal, renal, or lymphoid tumor | Neuroblastoma, Wilms tumor, lymphoma |

| Hypertension | Renal or adrenal tumor | Neuroblastoma, pheochromocytoma, Wilms tumor |

| Diarrhea | Vasoactive intestinal polypeptide | Neuroblastoma, ganglioneuroma |

| Soft tissue mass | Local or metastatic tumor | Ewing sarcoma, osteosarcoma, neuroblastoma, thyroid carcinoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis |

| Diabetes insipidus, galactorrhea, poor growth | Neuroendocrine involvement of hypothalamus or pituitary gland | Adenoma, craniopharyngioma, prolactinoma, Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis |

| Emesis, visual disturbances, ataxia, headache, papilledema, cranial nerve palsies | Increased intracranial pressure | Primary brain tumor; metastasis |

| OPHTHALMOLOGIC SIGNS | ||

| Leukokoria (white pupil) | Retinal mass | Retinoblastoma |

| Periorbital ecchymosis | Metastasis | Neuroblastoma |

| Miosis, ptosis, heterochromia | Horner syndrome: compression of cervical sympathetic nerves | Neuroblastoma |

| Opsomyoclonus, ataxia | Neurotransmitters? Autoimmunity? | Neuroblastoma |

| Exophthalmos, proptosis | Orbital tumor | Rhabdomyosarcoma, lymphoma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis |

| THORACIC MASS | ||

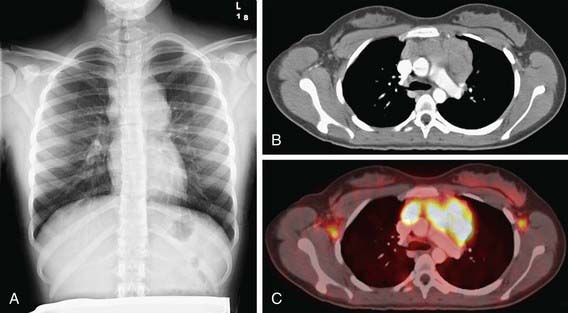

| Cough, stridor, pneumonia, tracheal-bronchial compression; superior vena cava syndrome | Anterior mediastinal | Germ cell tumor, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, Hodgkin lymphoma |

| Vertebral or nerve root compression; dysphagia | Posterior mediastinal | Neuroblastoma, neuroenteric cyst |

Modified from Kliegman RM, Marcdante KJ, Jenson HB, et al, editors: Nelson essentials of pediatrics, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2006, WB Saunders, p 729.

Table 487-3 UNCOMMON SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF CANCER IN CHILDREN

RELATED DIRECTLY TO TUMOR

NOT RELATED DIRECTLY TO TUMOR GROWTH

Modified from Vietti TJ, Steuber CP: Clinical assessment and differential diagnosis of the child with suspected cancer. In Pizzo PA, Poplack DG, editors: Principles and practice of pediatric oncology, ed 4, Philadelphia, 2002, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, pp 149–160.

Physical Examination

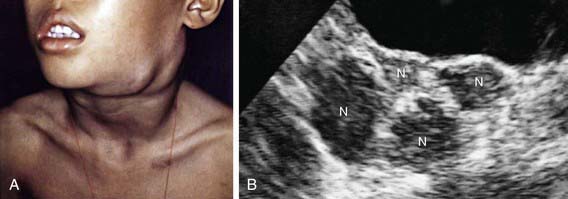

Physical examination findings in a child with malignancy are dependent on whether the cancer is systemic (see Table 487-2) or localized. The cancers most common in children involve the lymphohematopoietic system. When the bone marrow is compromised by malignancy (e.g., leukemia, disseminated neuroblastoma), typical findings include pallor from anemia, bleeding, petechiae, or purpura from thrombocytopenia or coagulopathy; cellulitis or other localized infection from leukopenia; skin nodules (especially in infants) and hepatosplenomegaly from malignant leukocytosis. Abnormalities found in lymphatic malignancies include peripheral adenopathy (Fig. 487-1) and signs of superior vena cava syndrome from an anterior mediastinal mass (Fig. 487-2) including respiratory distress, and facial and neck plethora and edema. Enlargement of cervical lymph nodes is common in children, but when persistent, progressive, and painless it often suggests lymphoma. In particular, supraclavicular adenopathy suggests underlying malignancy.

Abnormalities of the central nervous system that can indicate cancer include decreased level of consciousness, cranial nerve palsies, ataxia, afebrile seizures, ptosis, decreased visual activity, neuroendocrine deficits, and increased intracranial pressure, which may be diagnosed by the presence of papilledema (Fig. 487-3). Any focal neurologic deficit in the motor or sensory system, especially a decrease in cranial nerve function, should prompt further investigation for malignancy.

Figure 487-3 Papilledema on funduscopic examination.

(From Sinniah D, D’Angio GJ, Chatten J, et al: Atlas of pediatric oncology, London, 1996, Arnold.)

Ophthalmologic presentation of malignancy includes a white pupillary reflex (Fig. 487-4) rather than the usual red reflection from incident light. A white pupillary reflex is essentially pathognomonic for retinoblastoma, although some benign conditions can mimic this finding. Proptosis can be produced by rhabdomyosarcoma, neuroblastoma, lymphoma, and Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Horner syndrome, iris heterochromia, and opsoclonus-myoclonus all suggest a diagnosis of neuroblastoma.

Age-Related Manifestations

Because various types of cancer in children occur at specific ages, the physician should tailor the history and physical examination based on the age of the child. The embryonal tumors, including neuroblastoma, Wilms tumor, retinoblastoma, hepatoblastoma, and rhabdomyosarcoma, usually occur during the first 2 yr of life (see Fig. 485-4). From 1-4 yr of age, acute lymphoblastic leukemia peaks in incidence. Brain tumors have a peak incidence in the first decade of life. Non-Hodgkin lymphomas are uncommon earlier than 5 years of age and steadily increase thereafter. During adolescence, bone tumors, Hodgkin disease, and the gonadal and soft tissue sarcomas predominate. Hence, for infants and toddlers, special attention should be paid to the possibility of embryonal and intra-abdominal tumors. Preschool-aged and early school-aged children showing compatible signs and symptoms should be specifically evaluated for leukemia. School-aged children might present with lymphoma or with brain tumors. Adolescents require assessment for bone and soft tissue sarcomas and gonadal malignancies, as well as for Hodgkin lymphoma.

Early Detection

Early symptoms of leukemia may be limited to prolonged or unexplained low-grade fever or bone and joint pain. Blood counts with two or more cell lines abnormal might indicate the need for bone marrow examination, even when leukemic blast cells are not seen in the blood smear (see Tables 487-1 and 487-2).

Mass screening for children with malignancy is not feasible. A screening program to detect early-stage neuroblastoma was successful in documenting more cases of the disease, but it had no impact on overall outcome. However, certain children are at increased risk for cancer and require an individualized plan to ensure early detection of malignancy. Selected examples include children with certain chromosome abnormalities, such as Down syndrome, Klinefelter syndrome, WAGR syndrome (Wilms tumor, aniridia, genital abnormalities, and mental retardation); children with overgrowth syndromes, such as Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, and hemihypertrophy; children with certain inherited single-gene disorders, including retinoblastoma, p53 mutations (Li-Fraumeni syndrome), familial adenomatous polyposis, and neurofibromatosis. (See Table 486-2 for complete list.)

Ensuring the Diagnosis

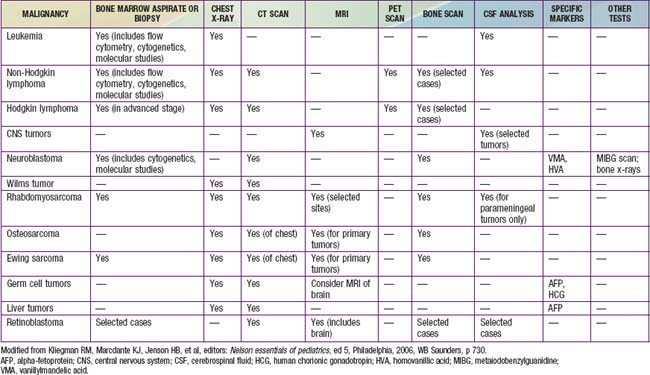

When a malignant neoplasm is suspected, the immediate goal is to confirm the diagnosis. A tentative diagnosis can often be established on the basis of the patient’s age, symptoms, and location of masses. Selected imaging techniques and tumor markers can facilitate the diagnostic approach (Table 487-4). Especially when a solid tumor is present, the pediatric oncologist, surgeon, and pathologist should work as a team to determine the site of biopsy, amount of tissue required, and whether fine-needle aspiration, percutaneous image-guided biopsy, incisional biopsy, or excisional biopsy and tumor resection are indicated. For selected situations, at the time of the initial diagnostic procedure, plans for bone marrow aspiration and biopsy and placement of central venous access may be appropriate.

Staging

Once a specific diagnosis is confirmed, studies to define the extent of the malignancy are necessary to determine prognosis and treatment. Table 487-4 outlines minimum evaluation for common pediatric malignancies. In addition, for many tumors (e.g., Wilms tumor, neuroblastoma, rhabdomyosarcoma) a surgical staging system is used. Surgical stage can be determined at the time of the initial diagnostic procedure or subsequently. For example, a patient who has abdominal surgery for possible Wilms tumor or neuroblastoma should have careful evaluation and biopsy of all adjacent lymph nodes. A child with rhabdomyosarcoma can require a subsequent biopsy of sentinel lymph nodes as determined by scintigraphy or dye injection adjacent to the primary tumor. The pathologist facilitates staging by examining margins of the specimen to determine residual tumor.

Bjornsson HT, Sigurdsson MI, Fallin MD, et al. Intra-individual change over time in DNA methylation with familial clustering. JAMA. 2008;299:2877-2883.

Blackburn E. Telomeres and telomerase: their mechanism of action and the effects of altering their functions. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:859-862.

Butel JS. Viral carcinogenesis: Revelation of molecular mechanisms and etiology of human disease. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:405-426.

Dong LM, Potter JD, White E, et al. Genetic susceptibility to cancer. JAMA. 2008;299:2423-2436.

Esteller M. Epigenetics in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1148-1158.

Foulkes WD. Inherited susceptibility to common cancers. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2143-2153.

Guillerman RP, Braverman RM, Parker BR. Imaging studies in the diagnosis and management of pediatric malignancies. In: Pizzo PA, Poplack DG, editors. Principles and practice of pediatric oncology. ed 5. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006:236-289. 2006

Malogolowkin M, Quinn JJ, Steuber CP, et al. Clinical assessment and differential diagnosis of the child with suspected cancer. In: Pizzo PA, Poplack DG, editors. Principles and practice of pediatric oncology. ed 5. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006:145-159. 2006

Reinhart B, Chaillet JR. Genomic imprinting: cis-acting sequences and regional control. Int Rev Cytol. 2005;243:173-213.

Sinniah D, D’Angio GJ, Chatten J, et al. Atlas of pediatric oncology. London: Arnold; 1996.

Triche TJ, Hicks J, Sorenson PHB. Diagnostic pathology of pediatric malignancies. In: Pizzo PA, Poplack DG, editors. Principles and practice of pediatric oncology,. ed 5. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006:185-235. 2006