Chapter 396 Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (Immotile Cilia Syndrome)

Normal Ciliary Ultrastructure and Function

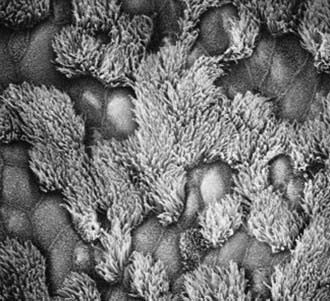

The upper and lower respiratory tracts are continuously exposed to inhaled pathogens, and local defenses have evolved to protect the airway. The respiratory epithelium in the nasopharynx, middle ear, paranasal sinuses, and larger airways are lined by a ciliated, pseudostratified columnar epithelium that is essential for mucociliary clearance (Fig. 396-1). Motile cilia are hairlike organelles that move fluids, mucus, and inhaled particulates vectorially from conducting airways, paranasal sinuses, and eustachian tubes.

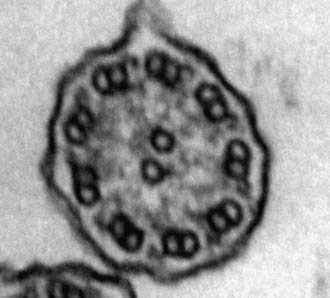

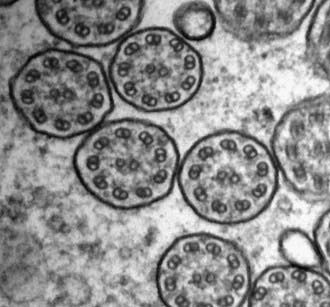

A mature ciliated epithelial cell has approximately 200 uniform motile cilia that are functionally and anatomically oriented in the same direction, moving with intracellular and intercellular synchrony. Anchored by a basal body to the apical cytoplasm and extending from the cell surface into the extracellular space, each cilium is a complex, specialized structure, composed of roughly 250 proteins. It contains a cylinder of microtubule doublets, arranged around a central pair of microtubules (Fig. 396-2), the characteristic “9+2” arrangement as viewed by cross-sectional views on electron microscopy. Multiple, different adenosine triphosphatases (ATPases), called dyneins, serve as “motors” of the cilium. Attached to the microtubules as distinct inner and outer dynein arms, dyneins cleave ATP to promote microtubule sliding, which is converted into bending. Nexin links and radial spokes act to restrict the degree of sliding between microtubules, allowing the cilium to bend.

A third distinct classification of cilia also exists, but only during embryonic development. These nodal cilia have a “9+0” microtubule arrangement similar to that of primary cilia, but they exhibit rotational movement, resulting in leftward flow of extracellular fluid that establishes body sidedness. Nodal cilia defects result in left-right body orientation abnormalities, such as situs ambiguus (Chapter 425.11).

Clinical Manifestations of Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (Table 396-1)

Table 396-1 CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS OF PRIMARY CILIARY DYSKINESIA

RESPIRATORY TRACT

Lung

Middle Ear

Paranasal Sinuses

GENITOURINARY TRACT

Male and female infertility

LEFT-RIGHT ORIENTATION DEFECTS

CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM

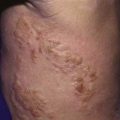

Most patients with PCD present in the newborn period shortly after birth with respiratory distress, which manifests as tachypnea, hypoxemia, or even respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation. The association of respiratory distress in term neonates with PCD has been underappreciated. Chronic cough and persistent rhinosinusitis have frequently been present since early infancy. In relation to upper respiratory involvement, the infant may have poor feeding and growth delays, similar to the effects of cystic fibrosis (Chapter 395), which can confound the diagnosis. Indeed, the upper respiratory tract is almost universally involved in PCD. Inadequate innate mucus clearance manifests as chronic sinusitis (Chapter 372) and nasal polyposis. Middle ear disease is common, with varying degrees of chronic otitis media leading to conductive hearing loss and myringotomy tube placement, which is often complicated by recurrent otorrhea.

Impaired mucociliary clearance of the lower respiratory tract leads to chronic cough secondary to recurrent pneumonia or bronchitis. Bacterial cultures of sputum or bronchial aspirates commonly yield nontypable Haemophilus influenzae (Chapter 186), Staphylococcus aureus (Chapter 174.1), Streptococcus pneumoniae (Chapter 175), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Chapter 197.1). Persistent airway infection and inflammation lead to bronchiectasis, even in preschool children. Clubbing is a sign of long-standing pulmonary involvement.

Retinitis pigmentosa has been linked with PCD. Intraflagellar transport proteins are essential for photoreceptor assembly, and when mutated, lead to their apoptosis within the retinal pigment epithelium (Chapter 622). X-linked retinitis pigmentosa has been associated with recurrent respiratory infections in families with RPGR gene mutations.

Diagnosis of Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia

Transmission electron microscopy is the current gold standard to assess ultrastructural defects within the cilium. Curettage from the nasal epithelium or bronchial brushing can provide an adequate specimen for review. Identification of a discrete, consistent defect in any aspect of the ciliary structure with concurrent phenotypic features is sufficient to make the diagnosis. Shortening or absence of dynein arms is the most common abnormality seen in PCD, accounting for 90% of cases with defined ultrastructural defects (Fig. 396-3). Other axonemal changes consistent with PCD include microtubular transposition, radial spoke and nexin link defects, and ciliary agenesis. Unfortunately, ultrastructural examination of cilia as a diagnostic test for PCD has significant drawbacks. Careful interpretation of the ultrastructural findings is necessary, because nonspecific, secondary changes may be seen in relation to exposure to environmental pollutants or infection. Ciliary defects can be acquired. Acute airway infection or inflammation can result in ultrastructural changes (compound cilia or blebs). Ciliary disorientation has also been proposed as a form of primary ciliary dyskinesia, but this phenomenon may be the result of airway injury. Frequently, the diagnosis of PCD can be delayed or missed because of inadequate tissue collection or sample processing as well as the lack of an experienced pathologist who can distinguish between primary and acquired ciliary defects. Several reviews have advocated culturing of airway epithelial cells and allowing the secondary changes to resolve. Nevertheless, the presence of normal axonemal ultrastructure does not exclude PCD.

Another approach exploits the observation that nasal nitric oxide (NO) concentrations are reduced in subjects with PCD. Because nasal NO measurements are relatively easy to perform and noninvasive, this method is a promising screen for PCD in patients >5 yr of age, provided that cystic fibrosis has been excluded (Chapter 395). Few studies in younger children have been reported, and the accuracy of nasal NO measurements in infants has not been established.

Bush A, Chodhari R, Collins N, et al. Primary ciliary dyskinesia: current state of the art. Arch Dis Child. 2007;92:1136-1140.

Bush A, Cole P, Hariri M, et al. Primary ciliary dyskinesia: diagnosis and standards of care. Eur Respir J. 1998;12:982-988.

Ibanez-Tallon I, Heintz N, Omran H. To beat or not to beat: roles of cilia in development and disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:R27-R35.

Kennedy MP, Omran H, Leigh MW, et al. Congenital heart disease and other heterotaxic defects in a large cohort of patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Circulation. 2007;115:2814-2821.

Knowles MR, Boucher RC. Mucus clearance as a primary innate defense mechanism for mammalian airways. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:571-577.

Leigh MW, Pittman JE, Carson JL, et al. Clinical and genetic aspects of primary ciliary dyskinesia and Kartagener syndrome. Genet Med. 2009;11:473-487.

Lie H, Ferkol T. Primary ciliary dyskinesia: recent advances in pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. Drugs. 2007;67:1883-1892.

Noone PG, Leigh MW, Sannuti A, et al. Primary ciliary dyskinesia: diagnostic and phenotypic features. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:459-467.