Presentation of the Patient with Pulmonary Disease

Dyspnea

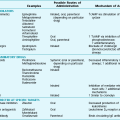

The differential diagnosis includes a broad range of disorders that result in dyspnea (Table 2-1). The disorders can be separated into the major categories of respiratory disease and cardiovascular disease. Dyspnea may be present in the absence of underlying respiratory or cardiovascular disease in conditions associated with increased respiratory drive, such as hyperthyroidism, or in metabolic disorders, such as mitochondrial myopathies. In addition, dyspnea may have an anxiety-related or psychosomatic origin.

Table 2-1

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF DYSPNEA

RESPIRATORY DISEASE

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE

INCREASED RESPIRATORY DRIVE

DISORDERS OF OXIDATIVE METABOLISM

ANXIETY/PSYCHOSOMATIC ORIGIN

The first major category consists of disorders at many levels of the respiratory system (airways, pulmonary parenchyma, pulmonary vasculature, pleura, and bellows) that can cause dyspnea. Airway diseases that cause dyspnea result primarily from obstruction to airflow, occurring anywhere from the upper airway to the large, medium, and small intrathoracic bronchi and bronchioles. Upper airway obstruction, which is defined here as obstruction above or including the vocal cords, is caused primarily by foreign bodies, tumors, edema (e.g., with anaphylaxis), and stenosis. A clue to upper airway obstruction is the presence of disproportionate difficulty during inspiration and an audible prolonged gasping sound called inspiratory stridor. The pathophysiology of upper airway obstruction is discussed in Chapter 7.

Airways below the level of the vocal cords, from the trachea down to the small bronchioles, are more commonly involved with disorders that produce dyspnea. An isolated problem, such as an airway tumor, usually does not by itself cause dyspnea unless it occurs in the trachea or a major bronchus. In contrast, diseases such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease have widespread effects throughout the tracheobronchial tree, with airway narrowing resulting from spasm, edema, secretions, or loss of radial support (see Chapter 4). With this type of obstruction, difficulty with expiration generally predominates over that with inspiration, and the physical findings associated with obstruction (wheezing, prolongation of airflow) are more prominent on expiration.

The term bellows is used here for the final category of respiratory-related disorders causing dyspnea. It refers to the pump system that works under the control of a central nervous system generator to expand the lungs and allow airflow. This pump system includes a variety of muscles (primarily but not exclusively diaphragm and intercostal) and the chest wall. Primary disease affecting the muscles, their nerve supply, or neuromuscular interaction, including polymyositis, myasthenia gravis, and Guillain-Barré syndrome, may result in dyspnea. Deformity of the chest wall, particularly kyphoscoliosis, produces dyspnea by several pathophysiologic mechanisms, primarily through increased work of breathing. Disorders of the respiratory bellows are discussed in Chapter 19.

Cough

The major causes of cough are listed in Table 2-2. Cough commonly results from an airway irritant, regardless of whether the person has respiratory system disease. The most common inhaled irritant is cigarette smoke. Noxious fumes, dusts, and chemicals also stimulate irritant receptors and result in cough. Secretions resulting from postnasal drip are a particularly common cause of cough, presumably triggering the symptom via stimulation of laryngeal cough receptors. Aspiration of gastric contents or upper airway secretions, which amounts to “inhalation” of liquid or solid material, can result in cough, the cause of which may be unrecognized if the aspiration has not been clinically apparent. In the case of gastroesophageal reflux, in which gastric acid flows retrograde into the esophagus, cough is due not only to aspiration of gastric contents from the esophagus or pharynx into the tracheobronchial tree, but also to reflex mechanisms triggered by acid entry into the lower esophagus and mediated by the vagal nerve.

Table 2-2

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF COUGH

AIRWAY IRRITANTS

AIRWAYS DISEASE

PARENCHYMAL DISEASE

CONGESTIVE HEART FAILURE

MISCELLANEOUS

In clinical practice, cough is often divided into three major temporal categories: acute, subacute, or chronic, depending on the duration of the symptom. Acute cough, defined by a duration of less than 3 weeks, is most commonly due to an acute viral infection of the respiratory tract, such as the common cold. Subacute cough is defined by a duration of 3 to 8 weeks, and chronic cough lasts 8 or more weeks. Whereas chronic bronchitis is a particularly frequent cause of cough in smokers, common causes of either subacute or chronic cough in nonsmokers are postnasal drip (also called upper airway cough syndrome), gastroesophageal reflux, and asthma. An important subacute cough is postinfectious cough that lasts for more than 3 weeks following an upper respiratory tract infection. It often is due to persistent airway inflammation, postnasal drip, or bronchial hyperresponsiveness (as seen with asthma). In all cases, however, the clinician must keep in mind the broader differential diagnosis of cough outlined in Table 2-2, recognizing that cough may be a marker and the initial presenting symptom of a more serious disease, such as carcinoma of the lung.

Hemoptysis

The major causes of hemoptysis can be divided into three categories based on location: airways, pulmonary parenchyma, and vasculature (Table 2-3). Airway disease is the most common cause, with bronchitis, bronchiectasis, and bronchogenic carcinoma leading the list. Bronchial carcinoid tumor (formerly called bronchial adenoma), a less common neoplasm with variable malignant potential, also originates in the airway and may cause hemoptysis. In patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, hemoptysis may be due to endobronchial (and/or pulmonary parenchymal) involvement with Kaposi sarcoma.

Table 2-3

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF HEMOPTYSIS

AIRWAYS DISEASE

Bronchial carcinoid tumor (bronchial adenoma)

Other endobronchial tumors (Kaposi sarcoma, metastatic carcinoma)

PARENCHYMAL DISEASE

VASCULAR DISEASE

MISCELLANEOUS/RARE CAUSES

Parenchymal causes of hemoptysis frequently are infectious in nature: tuberculosis, lung abscess, pneumonia, and localized fungal infection (generally attributable to Aspergillus organisms), termed mycetoma (“fungus ball”) or aspergilloma. Rarer causes of parenchymal hemorrhage are Goodpasture syndrome, idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis, and Wegener granulomatosis, some of which are discussed in Chapter 11.

Chest Pain

A variety of disorders originating in the mediastinum may result in pain; they may or may not be associated with additional problems in the lung itself. These disorders of the mediastinum are discussed in Chapter 16.

Harver, A, Mahler, DA, Schwartzstein, RM, et al. Descriptors of breathlessness in healthy individuals: distinct and separable constructs. Chest. 2000;118:679–690.

Heinicke, K, Taivassalo, T, Wyrick, P, et al. Exertional dyspnea in mitochondrial myopathy: clinical features and physiological mechanisms. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2011;301:R873–874.

Lenfant, C. Chest pain of cardiac and noncardiac origin. Metabolism. 2010;59(Suppl 1):S41–S46.

Luce, JM, Luce, JA. Management of dyspnea in patients with far-advanced lung disease. JAMA. 2001;285:1331–1337.

Mahler, DA, Selecky, PA, Harrod, CG, et al. American College of Chest Physicians consensus statement on the management of dyspnea in patients with advanced lung or heart disease. Chest. 2010;137:674–691.

Muroi, Y, Undem, BJ. Targeting peripheral afferent nerve terminals for cough and dyspnea. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2011;11:254–264.

Nausherwan, KB, Lee, LY. Mechanisms of dyspnea. Chest. 2010;138:1196–1201.

O’Donnell, DE, Ora, J, Webb, KA, et al. Mechanisms of activity-related dyspnea in pulmonary diseases. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2009;167:116–132.

Parshall, MB, Schwartzstein, RM, Adams, L, et al. An official American Thoracic Society statement: Update on the mechanisms, assessment, and management of dyspnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:435–452.

Scano, G, Stendardi, L, Grazzini, M. Understanding dyspnea by its language. Eur Respir J. 2005;25:380–385.

Benich, JJ, 3rd., Carek, PJ. Evaluation of the patient with chronic cough. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84:887–892.

Birring, SS. Controversies in the evaluation and management of chronic cough. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:708–715.

Canning, BJ. Afferent nerves regulating the cough reflex: mechanisms and mediators of cough in disease. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2010;43:15–25.

Chummun, D, Lü, H, Qiu, Z. Empiric treatment of chronic cough in adults. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2011;32:193–197.

Cornia, PB, Hersh, AL, Lipsky, BA, et al. Does this coughing adolescent or adult patient have pertussis? JAMA. 2010;304:890–896.

Gibson, PG, Fujimara, M, Niimi, A. Eosinophilic bronchitis: clinical manifestations and implications for treatment. Thorax. 2002;57:178–182.

Irwin, RS, Baumann, MH, Bolser, DC, et al. Diagnosis and management of cough: executive summary. ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2006;129:1S–23S.

Irwin, RS. Unexplained cough in the adult. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2010;43:167–180.

Kwon, NH, Oh, MJ, Min, TH, et al. Causes and clinical features of subacute cough. Chest. 2006;129:1142–1147.

Mazzone, SB, McGovern, AE, Cole, LJ, et al. Central nervous system control of cough: pharmacological implications. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2011;11:265–271.

Muroi, Y, Undem, BJ. Targeting peripheral afferent nerve terminals for cough and dyspnea. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2011;11:254–264.

Smith, JA, Abdulqawi, R, Houghton, LA. GERD-related cough: pathophysiology and diagnostic approach. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2011;13:247–256.

Morice, AH, McGarvey, L, Pavord, I, Thoracic, British. Society Cough Guideline Group: BTS guidelines: recommendations for the management of cough in adults. Thorax. 2006;61(Suppl 1):i1–i24.

Andersen, PE. Imaging and interventional radiological treatment of hemoptysis. Acta Radiol. 2006;47:780–792.

Bidwell, JL, Pachner, RW. Hemoptysis: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72:1253–1260.

Chun, JY, Morgan, R, Belli, AM. Radiological management of hemoptysis: a comprehensive review of diagnostic imaging and bronchial arterial embolization. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2010;33:240–250.

Dudha, M, Lehrman, S, Aronow, WS, et al. Hemoptysis: diagnosis and treatment. Compr Ther. 2009;35:139–149.

Jean-Baptiste, E. Clinical assessment and management of massive hemoptysis. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:1642–1647.

Sakr, L, Dutau, H. Massive hemoptysis: an update on the role of bronchoscopy in diagnosis and management. Respiration. 2010;80:38–58.

Savale, L, Parrot, A, Khalil, A, et al. Cryptogenic hemoptysis: from a benign to a life-threatening pathologic vascular condition. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:1181–1185.

Branch, WT, Jr., McNeil, BJ. Analysis of the differential diagnosis and assessment of pleuritic chest pain in young adults. Am J Med. 1983;75:671–679.

Brims, FJ, Davies, HE, Lee, YC. Respiratory chest pain: diagnosis and treatment. Med Clin North Am. 2010;94:217–232.

Brown, AF, Cullen, L, Than, M. Future developments in chest pain diagnosis and management. Med Clin North Am. 2010;94:375–400.

Ebell, MH. Evaluation of chest pain in primary care patients. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83:603–605.

Goldberg, A, Litt, HI. Evaluation of the patient with acute chest pain. Radiol Clin North Am. 2010;48:745–755.

Lenfant, C. Chest pain of cardiac and noncardiac origin. Metabolism. 2010;59(Suppl 1):S41–S46.

Lee, TH, Goldman, L. Evaluation of the patient with acute chest pain. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1187–1195.

Winters, ME, Katzen, SM. Identifying chest pain emergencies in the primary care setting. Prim Care. 2006;33:625–642.

Yelland, M, Cayley, WE, Jr., Vach, W. An algorithm for the diagnosis and management of chest pain in primary care. Med Clin North Am. 2010;94:349–374.