Preoperative evaluation of the patient with cardiac disease for noncardiac operations

Defining comorbid conditions

The clinician needs to identify any active cardiac conditions (Table 106-1) or clinical risk factors that have been associated with adverse outcomes. Active cardiac conditions are defined as unstable coronary syndromes, decompensated systolic or diastolic heart failure, significant arrhythmias, and severe valvular heart disease. Clinical risk factors are independent risk factors that are associated with poor outcomes and include history of ischemic heart disease (suggestive history, symptoms, or Q waves on electrocardiogram), history of prior or compensated heart failure (suggestive history, symptoms, or examination findings), history of stroke or transient ischemic attack, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, and renal insufficiency (serum creatinine concentration >2 mg/dL).

Table 106-1

Active Cardiac Conditions That Mandate Preoperative* Evaluation and Treatment

| Condition | Examples |

| Unstable coronary syndromes | Unstable or severe angina† (CCS class III or IV)‡ Recent MI§ |

| Decompensated HF (NYHA functional class IV; worsening or new-onset HF) | |

| Significant arrhythmias | High-grade AV block Mobitz type II AV block Third-degree AV block Symptomatic ventricular arrhythmias Supraventricular arrhythmias, including AF, with uncontrolled ventricular rate (HR >100 beats/min at rest) Symptomatic bradycardia Newly recognized ventricular tachycardia |

| Severe valvular disease | Severe aortic stenosis (mean pressure gradient >40 mm Hg, aortic valve area <1.0 cm2, or symptomatic Symptomatic mitral stenosis (progressive dyspnea on exertion, exertional presyncope, or HF) |

*Before noncardiac operations.

†According to Campeau L. Letter: Grading of angina pectoris. Circulation. 1976;54:522-523.

‡May include “stable” angina in patients who are sedentary.

§The American College of Cardiology (ACC) National Database Library defines “recent” myocardial infarction (MI) as occurring >7 days but ≤30 days previously.

Reprinted, with permission, from Fleisher L, Beckman J, Brown K, et al. ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and care for noncardiac surgery: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:e159-241.

Assessing surgical risk

Evaluation of surgical risk is crucial. Surgical procedures have been classified as low-risk, intermediate-risk, and high-risk vascular operations (Table 106-2). Understandably, procedures with differing levels of stress (alterations in heart rate, blood pressure, intravascular volume, blood loss, and pain) are associated with differing levels of morbidity and mortality risks. Ophthalmologic and superficial procedures represent the lowest risk and very rarely result in morbidity and death. The intermediate-risk category (includes endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair and carotid endarterectomy) represents procedures with associated morbidity and mortality risks that vary depending upon the surgical location and extent of procedure. Major vascular procedures are the highest risk procedures and mandate further investigation. In the revised ACC/AHA guidelines, vascular surgery is now the only surgical category listed as high risk or generally associated with a greater than 5% risk of perioperative cardiac complications.

Table 106-2

Surgical Risk* Stratification for Patients with Preexisting Cardiac Disease

| Level of Risk | Procedure Examples |

| High (vascular procedures)† | Aortic and other vascular operations Peripheral vascular operations |

| Intermediate‡ | Intraperitoneal and intrathoracic operations Carotid endarterectomy Head and neck operation Orthopedic operations Prostate operations |

| Low§ | Endoscopic procedures Superficial procedures Cataract operations Breast operations Ambulatory operations |

*Combined incidence of cardiac death and nonfatal myocardial infarction.

†Reported cardiac risk often >5%.

‡Reported cardiac risk generally 1%-5%.

§Reported cardiac risk generally <1%. These procedures do not generally require further preoperative cardiac testing.

Evaluating functional status

Assessment of functional status in the patient with cardiovascular and pulmonary disease is critical, because O2 uptake is considered to be the best measure of cardiovascular reserve and exercise capacity. Functional status is measured using metabolic equivalents (METS) (Table 106-3). One MET represents the O2 consumption of a person at rest (3-5 mL·kg−1·min−1). A functional capacity of 4 METs is considered the minimum requirement for a patient undergoing a major surgical procedure. Consequently, patients who are unable to meet a minimum 4-MET demand during daily activities are at higher risk for developing perioperative cardiovascular and pulmonary complications. Those patients with multiple medical comorbid conditions that limit activity will need to be formally tested to objectively determine cardiopulmonary reserve.

Table 106-3

Energy Requirement for Various Activities

| Energy Expenditure | Can You . . . |

| 1 MET ↓ |

Take care of yourself? Eat, dress, or use the toilet? Walk indoors around the house? Walk a block or two on level ground at 2 to 3 mph (3.2 to 4.8 kph)? |

| 4 METs ↓ |

Do light work around the house, like dusting or doing dishes? Climb a flight of stairs or walk up a hill? Walk on level ground at 4 mph (6.4 kph)? Run a short distance? Do heavy work around the house, like scrubbing floors or lifting or moving heavy furniture? |

| >10 METs | Participate in moderate recreational activities, like golf, bowling, dancing, doubles tennis, or throwing a football or baseball? |

kph, Kilometers per hour; MET, metabolic equivalent; mph, miles per hour.

Reprinted, with permission, from Fleisher L, Beckman J, Brown K, et al. ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and care for noncardiac surgery: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:e159-241.

Applying the revised american college of cardiology/american heart association guidelines

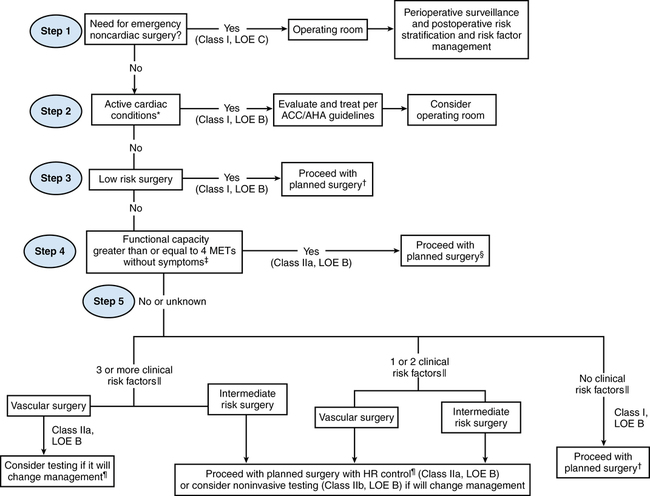

Once the clinician has performed a history and examination, the new 5-step ACC/AHA approach can then be utilized for risk stratification and determination of the need for additional cardiac testing (Figure 106-1).

Step 1. Is the noncardiac operation emergent? If so, the patient is taken to the operating room without delay, with the focus being appropriate intraoperative and postoperative cardiac surveillance.

Step 2. Is an active cardiac condition identified? If so, this mandates cardiology consultation and further diagnostic testing.

Step 3. Is the operation low risk? Recognizing that the risk for perioperative cardiac complications in low-risk operations is less than 1% even in high-risk patients, the guidelines state that the patient may proceed to surgery without further testing.

Step 4. If the patient demonstrates good functional capacity (being able to perform >4 METS of activity without cardiopulmonary symptoms) the patient may proceed to surgery.

Step 5. Patients with poor or indeterminate functional capacity for intermediate-risk or high-risk procedures must undergo an additional evaluation. The key issue here is the number of clinical predictors (derived from the Revised Cardiac Risk Index): patients with no clinical risk factors may proceed to surgery. Patients with one or two risk factors may proceed to surgery with heart rate control; noninvasive testing may be considered only if it will change management. Patients with three or more clinical risk factors warrant more scrutiny. These patients scheduled for vascular operations should be considered for noninvasive testing—if it will change management. On the other hand, even those with three or more risk factors scheduled for intermediate-risk operations should proceed to surgery with perioperative heart rate control. Noninvasive testing for this group should, again, be considered only if it will change management.