CHAPTER 7 Preoperative care

Choosing the Operation

Choosing the optimum surgical procedure is a crucial first step in the preoperative care of patients. All management options should be carefully considered after full and thorough assessment of the patient’s gynaecological as well as other coexisting medical conditions. All treatment options should be explored including no treatment, non-surgical alternatives or more conservative surgery. For example, a patient requesting sterilization should be informed about reversible long-term contraception, and she and her partner should be informed about vasectomy. Likewise, a patient requesting hysterectomy for menorrhagia should be informed of the reversible progestogen-releasing intrauterine system or less invasive endometrial ablation. It is the clinician’s duty to make the patient fully aware of all her options. All the pros and cons and implications of various treatments as well as no treatment should be fully explained to patients. The final decision on the optimum treatment should be mutually agreed between the surgeon and the patient, taking into consideration her wishes and social circumstances (General Medical Council 2008). Quite often, patients do not remember all the information given to them verbally during their consultation. It is therefore important to hand them printed leaflets containing more detailed information on their intended procedure, as well as other relevant treatments. These should also be available in languages other than English depending on the local demographics. With the availability of information on the Internet, patients are very likely to read up on their intended procedures from various unknown Internet sources. Clinicians should therefore direct their patients towards trusted websites offering unbiased information, such as that of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists which provides specific information leaflets for patients.

Consent

Valid consent

It is a legal requirement and an ethical principle to obtain valid consent before starting any treatment or investigation. Although verbal consent is acceptable for most investigations and medical treatments, it is necessary to obtain written and signed consent before any surgical intervention under anaesthesia, with the exception of some emergency situations. For consent to be valid, it must be given voluntarily by an appropriately informed person (either the patient or someone with parental responsibility if the patient is under 16 years of age) who has the capacity to consent to the intervention. The woman must be informed regarding the nature of her condition. Written information should be given, especially as patients are often admitted on the day of surgery and have less time to ask questions. As discussed above, the patient must also be aware of the alternatives to surgery and the option of no treatment. The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, the General Medical Council and the Department of Health all place importance and have provided guidance on valid consent (Department of Health 2001, General Medical Council 2008, Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists 2008a).

Consent and operative risks

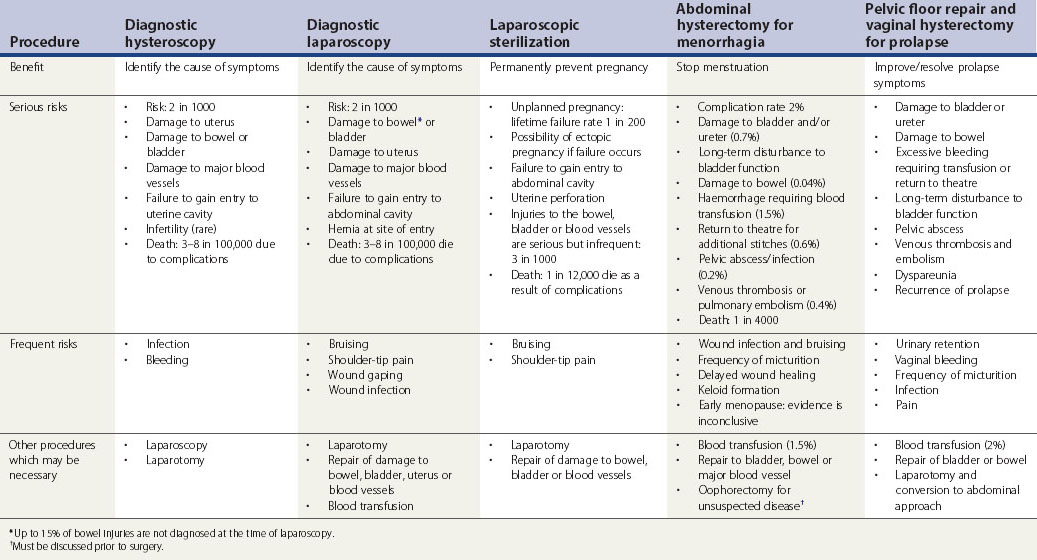

Patients should be informed of frequent and established serious adverse outcomes related to the procedure. The likelihood of complications associated with the intended surgical procedure should be presented in a fashion comprehensible to the patient. The discussion should include all possible intraoperative risks as well as short- and long-term postoperative complications. Table 7.1 summarizes the risks associated with common gynaecological operations as detailed by the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (2004a–c, 2008a–d).

Consent for additional procedures

It is always good practice to discuss, and include in the consent, any possible additional procedures that may be required during the intended operation. Generally, any additional surgical treatment which has not previously been discussed with the woman should not be performed, even if this means a second operation (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists 2008a). One must not exceed the scope of authority given by the woman, except in a life-threatening emergency. There are three different situations where an additional procedure may be necessary during the course of an elective surgery. Firstly, when a minor pathology related to the patient’s symptoms is detected such as endometriosis or adhesions in women undergoing laparoscopy for pelvic pain or infertility. In this situation, treatment can be performed if the patient has been made aware of this possibility and has consented for additional minor treatment. The second situation arises when a more complex disease is detected such as a pelvic mass, suspicious looking ovary, severe endometriosis or severe adhesions. Surgery in these situations should be deferred to a second operation after adequate counselling of the patient. In particular, oophorectomy for unexpected disease detected at surgery should not normally be performed without previous consent. The third situation involves intraoperative complications such as injury to the bowel or urinary tract that could lead to serious consequences if left untreated. Corrective surgery must proceed in these cases, and full explanation should be given as soon as practical following surgery.

Who should obtain the consent?

It is the responsibility of the clinician undertaking the surgical procedure to obtain consent. However, if this is not possible, it may be delegated to another doctor who is adequately trained and has sufficient knowledge of the procedure to be performed (General Medical Council 2008). The consent, however, remains the responsibility of the surgeon performing the operation. The clinician obtaining the consent should see the patient on her own first, for at least part of the consultation. She should then be allowed the company of a trusted friend or relative for support if she wishes. If consent is taken on the day of surgery, enough time should be allowed for discussion (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists 2008a).

Additional consents

Duration of consent

The consent will remain valid indefinitely unless withdrawn. However, if new information is available between the consent and the procedure (e.g. new evidence of risk or new treatment options), the doctor should inform the patient and reconfirm the consent. It is also wise to refresh the consent form if there is a significant amount of time between consent and the intervention (Department of Health 2001).

Consent of special groups of patients

Jehovah’s Witnesses

Jehovah’s Witnesses are an Adventist sect of Christianity founded in the USA in the late 19th Century. They believe that accepting a blood transfusion, even autologous blood transfusions in which one’s own blood is stored for later transfusion, is a sin. This includes red blood cells, white blood cells, platelets and plasma. Jehovah’s Witnesses are aware of the possible risk to life in refusing blood transfusion and they take full responsibility for this. It is important to respect their wishes and to consider alternative measures to blood transfusion. There are special consent forms for Jehovah’s Witnesses’ refusal of blood products, stating clearly that this may result in the death of the patient. They also specify what blood fractions they might accept (e.g. interferons, interleukins, albumin, clotting factors or erythropoietin) as well as any blood salvage procedures, such as cell saver that recycles and cleans blood from a patient and redirects it to the patient’s body. More information can be found on the official website of Jehovah’s Witnesses (www.watchtower.org).

Adults without capacity

The Mental Capacity Act 2005

Certain procedures such as sterilization, management of menorrhagia and abortion do occasionally arise in women with severe learning disabilities who lack capacity to consent. They give special concern about the best interests and human rights of the person who lacks capacity. They can be referred to court if there is any doubt that the procedure is the most appropriate therapeutic recourse. The least invasive and reversible option should always be favoured (Department of Health 2001).

Children and young people

Finally, refusal of treatment by a competent child and persons with parental responsibility for a child can be over-ruled by a court if this is in the best interests of the child (Department of Health 2001).

Preoperative Assessment

Risk assessment

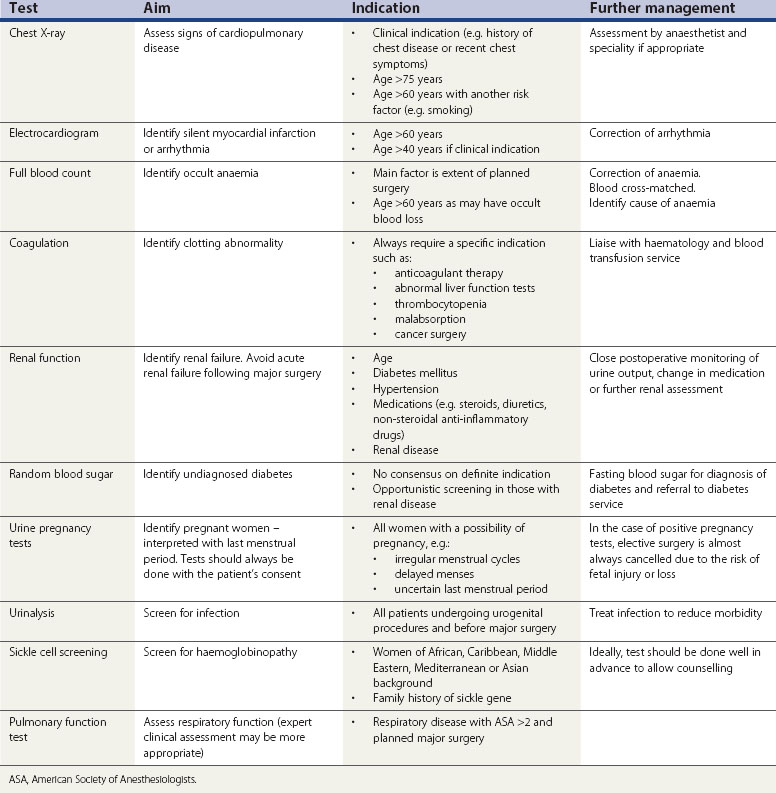

One should start with a thorough assessment of the patient’s risk by way of a full medical and surgical history followed by general examination. This will determine which patients require further investigations. Routine preoperative testing of healthy individuals is of little benefit. Guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2003) conclude that no routine laboratory testing or screening is necessary for preoperative evaluation unless there is a relevant clinical indication. Preoperative testing is a substantial drain on NHS resources, and substantial savings can be achieved by eliminating unnecessary investigations (Munro et al 1997). False-positive results may also cause unnecessary anxiety and result in additional investigations causing a delay in surgery. The indications and aims of common preoperative tests are shown in Table 7.2.

Purpose of preoperative risk assessment

Assessing patients’ suitability for day surgery

Risk assessment of obese patients

The prevalence of obesity is increasing in the Western world. Obesity is defined as a body mass index (BMI) of more than 30 kg/m2 and morbid obesity is defined as a BMI of more than 40 kg/m2. Although absolute BMI should not be used as a sole indicator for suitability for surgery or its location, it is the most useful currently available measure of risk. People who are mildly obese pose few additional problems, but those who are morbidly obese have increased health risks associated with surgery. Table 7.3 summarizes common comorbidities in obese patients. They require extra time and early communication before surgery regarding scheduling of surgery, provision for sufficient operative time, resources and personnel (Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland 2007).

| Respiratory |

Preoperative Preparation

Thromboprophylaxis

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) kills 25,000 people per year in England. This is more than breast cancer or road traffic accidents. The incidence of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) in gynaecological surgery with no prophylaxis is 16% and the incidence of symptomatic pulmonary embolism (PE) is 1%. VTE usually occurs 1–2 weeks following surgery. DVT is commonly asymptomatic but may result in sudden death from PE or long-term morbidity secondary to venous insufficiency and post-thrombotic syndrome (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence 2007).

In order to minimize the risk of VTE in patients undergoing surgery, each patient should be assessed carefully for individual risk factors. Box 7.1 details patient-related risk factors for VTE.

Ample hydration and early mobilization

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2007) has recommended thromboprophylaxis regimens for gynaecological surgery. Mechanical prophylaxis should be used in all patients with no risk factors for VTE. Pharmacological prophylaxis should be considered in the presence of any risk factors for VTE.

Pharmacological prophylaxis

Pharmacological prophylaxis should be considered in patients undergoing surgery in the presence of any additional risk factors, as summarized in Box 7.1. Low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) should be offered in preference to unfractionated heparin. Fondaparinux can be offered as an alternative, within its licensed indications.

Antibiotic prophylaxis

Surgical infections include infections of surgical wounds or tissues involved in the operation, occurring within 30 days of surgery. They prolong hospital stay and are an important outcome measure for surgical procedures. Surgical infections are caused by direct contact from surgical instruments or hands, from air contaminated with bacteria or by the patient’s endogenous flora of the operation site. Additional risk factors for surgical site infections are shown in Table 7.4. The most causative organisms are Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes and enterococci.

| Patient related | Operation related |

|---|---|

| Extremes of age | Length of operation |

| Poor nutritional state | Skin antisepsis |

| Obesity | Preoperative skin shaving |

| Diabetes mellitus | Inadequate sterilization of equipment |

| Smoking | Poor surgical technique and tissue handling |

| Coexisting infection | |

| Bacterial colonization (e.g. methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus) | |

| Immunosuppression | |

| Prolonged hospital stay |

Prophylactic antibiotics should ideally be given intravenously at anaesthetic induction or no more than 30 min before. This should ensure the maximum blood concentration at the time of skin incision and entry to the genitourinary tract when blood contamination occurs. If given too early, antibiotics could increase the resistance among colonizing organisms. On the other hand, late administration of prophylactic antibiotics will reduce their efficacy, especially if given more than 3 h after the start of the procedure. A single-dose prophylactic antibiotic is effective. Multiple doses may be necessary when surgery is prolonged and where there is a major blood loss of more than 1.5 l requiring fluid resuscitation, which results in reduction of the antibiotic concentration. Prolonged use of prophylactic antibiotics for more than 24 h should be avoided as it could result in an increase in resistant organisms (Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network 2008).

A system of classification for operative wounds based on the degree of microbial contamination was developed by the US National Research Council group in 1964 (Berard and Gandon 1964, Culver et al 1991). Four wound classes with an increasing risk of surgical site infection were described: clean, clean-contaminated, contaminated and dirty (Table 7.5). Most gynaecological procedures fall into the ‘clean-contaminated’ category. Hence, prophylactic antibiotics are highly recommended for certain procedures. However, the final decision rests with the surgeon who should assess the risks and benefits for that patient. There is good research evidence supporting the use of prophylactic antibiotics for vaginal and abdominal hysterectomy with a significant reduction in the incidence of febrile morbidity, pelvic infection and wound infection.

Table 7.5 Wound classification and risk of infection

| Classification | Description | Infective risk |

|---|---|---|

| Clean |

Urine and respiratory infection

Prophylactic antibiotics are not recommended for the sole prevention of respiratory or urinary tract infections. Although meta-analyses do show a significant reduction in the incidence of urinary tract infection, the results for respiratory tract infection are equivocal. Patients at higher risk of a urinary tract infection (e.g. elderly women and those with indwelling catheters) are more likely to develop bacterial resistance and C. difficile due to prophylactic antibiotics (Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network 2008).

Antibiotic prophylaxis against infective endocarditis

Infective endocarditis is a rare condition affecting less than one in 10,000 cases, but with significant morbidity and mortality of up to 20% (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence 2008). It is inflammation of the myocardium, which occurs following bacteraemia in a patient with a predisposing cardiac condition. Pathogens are likely to be commensal organisms, the most common being Streptococcus viridans, S. aureus and enterococci (Gould et al 2006). Up to 75% of cases of infective endocarditis occur without a preceding interventional or dental procedure to account for bacteraemia. Furthermore, there is no consistent association between having an interventional procedure and infective endocarditis. Antibiotic prophylaxis has been shown to reduce the incidence of bacteraemia following an interventional procedure, but does not eliminate it (Bhattacharya et al 1995). The clinical effectiveness of prophylactic antibiotics remains to be proven.

There is not enough evidence in the literature to show an increased risk of infective endocarditis in women undergoing genitourinary procedures. The large number of gynaecological procedures undertaken would mean that the risks of antibiotic prophylaxis against infective endocarditis (e.g. anaphylaxis and bacterial resistance) might outweigh the benefit. The British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy states that there are no good epidemiological data on the impact of bacteraemia from non-dental procedures on the risk of developing infective endocarditis (Gould et al 2006). Likewise, the current guidelines of the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2008) suggest that antibiotic prophylaxis is not recommended for people undergoing genitourinary tract procedures.

Weight loss

As discussed above, obesity is a major risk factor and is associated with an increase in the incidence of most surgical complications in gynaecological patients. In addition, obesity increases the technical difficulty and prolongs surgery. Obese women should therefore be strongly encouraged to reduce their weight before their planned surgery. However, preoperative weight loss must be controlled and preferably supervised as obese patients often have poor nutritional status, despite their excess weight. A very low calorie diet can be dangerous and may cause cardiac arrhythmias or even sudden death. Women who have undergone bariatric surgery could develop malabsorption. A supervised exercise programme may be best to help with weight loss, exercise tolerance and glucose tolerance (Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland 2007).

Smoking cessation

Smokers have a substantially increased risk of intra- and postoperative complications. They are three to six times more likely to have intraoperative pulmonary complications and postoperative wound infections. Preoperative assessment is a good opportunity to offer smoking cessation intervention, as the patient may be more motivated. This approach has been shown to be effective in reducing preoperative smoking. However, whether or not smoking cessation of such short duration would lead to decreased operative complication rates remains to be determined (Møller and Villebro 2005).

Bowel preparation

Bowel preparation may be considered before gynaecological operations in patients with complex pelvic diseases involving the bowel, such as severe endometriosis, extensive adhesions or malignancy. In such cases, bowel preparation may be necessary if bowel surgery is anticipated or to provide better access for the surgeon. However, a large randomized trial investigating the value of preoperative bowel preparation in patients undergoing bowel resection and anastomosis showed no significant difference in the rate of anastomosis breakdown in women who received mechanical bowel preparation compared with those who did not (Contant et al 2007). However, patients experiencing anastomotic breakdown were less likely to develop an abscess if they had bowel preparation.

Bowel preparation has not been shown to improve the view of the operating field during laparoscopy. Furthermore, it may add to the patient’s inconvenience and discomfort during her preoperative hospital stay (Muzzi et al 2006, Lijoi et al 2009).

Additional medications prior to gynaecological surgery

Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone analogues

Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues can be used before fibroid surgery and endometrial ablation. GnRH analogues taken for 3–4 months prior to fibroid surgery (myomectomy or hysterectomy) have been shown to decrease uterine and fibroid size, and to improve menhorrhagia after surgery; and to reduce intraoperative blood loss, thereby improving pre- and postoperative haemoglobin levels. In reducing the fibroid size, GnRH analogues can also decrease the rate of vertical abdominal incisions, and reduce the operating time and hospital stay. However, these benefits of GnRH analogues should be balanced against their associated side-effects such as menopausal symptoms (Lethaby et al 2002).

GnRH analogues may also be of value in women undergoing endometrial ablation or resection to help thin out the endometrium. An alternative approach is to perform the procedure shortly after cessation of menstruation when the endometrium is at its thinnest. GnRH analogues are associated with shorter surgery time and increased rate of postoperative amenorrhoea with endometrial resection. However, this benefit does not seem to last in the long term and does not extend to second-generation ablation treatments (Sowter et al 2002)

Misoprostol

Misoprostol is the most commonly used cervical priming agent worldwide. The most common use is in first-trimester abortion or for surgical management of miscarriage. It is effective in cervical softening and dilatation before surgery. However, there is not enough evidence to conclude that misoprostol is necessary to reduce complications such as cervical laceration. An alternative is Laminaria, although this requires administration to the endocervix via a speculum. Misoprostol can be administered vaginally and sublingually with similar effect, although the sublingual route has more side-effects. It can also be given orally but needs to be administered up to 12 h before surgery (Allen and Goldberg 2007).

Pre-existing medications

Oral contraception

The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists advises that the COCP should ideally be discontinued at least 4 weeks prior to major surgery where immobilization is expected. Discontinuation of the COCP has been shown to reduce the postoperative VTE rate from 1% to 0.5%. This small absolute risk reduction must be balanced against the risks of discontinuing an effective contraception with the risk of unplanned pregnancy (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists 2004a). Table 7.6 shows the World Health Organization’s recommendations for contraceptive use in surgery.

Table 7.6 World Health Organization eligibility criteria for contraceptive use in surgery

| Contraceptive | Type of surgery | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Combined oral contraceptive pill | Minor surgery | Unrestricted use |

| Major surgery without immobilization | Benefits outweighs risk | |

| Major surgery with prolonged immobilization | Unacceptable risk | |

| Progestogen-only pill | All surgery | Benefits outweigh risk |

KEY POINTS

Allen RH, Goldberg AB. Cervical dilation before first-trimester surgical abortion (<14 weeks gestation). Contraception. 2007;76:139-156.

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. Perioperative Management of the Morbidly Obese Patient. London: AAGBI; 2007.

Berard F, Gandon J. Postoperative wound infections: the influence of ultraviolet irradiation of the operating room and of various other factors. Annals of Surgery. 1964;160(Suppl 1):1-192.

Bhattacharya S, Parkin DE, Reid TMS, et al. A prospective randomised study of the effects of prophylactic antibiotics on the incidence of bacteraemia following hysteroscopic surgery. European Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1995;63:37-40.

Contant CM, Hop WC, Van’t Sant HP, et al. Mechanical bowel preparation for elective colorectal surgery: a multicentre randomized trial. The Lancet. 2007;370:2112-2117.

Culver DH, Horan TC, Gaines RP, et al. Surgical wound infection rates by wound class, operative procedure and patient risk. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance system. American Journal of Medicine. 1991;91:152S-157S.

Department of Health. Reference Guide to Consent for Examination or treatment. London: DoH; 2001.

Department of Health. Day Surgery Operational Guide — Waiting, Booking and Choice. London: DoH; 2002.

General Medical Council. Consent: Patients and Doctors Making Decisions Together. London: GMC; 2008.

Gould FK, Elliott TSJ, Foweraker J, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of endocarditis: report of the Working Party of the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2006;58:896-898.

Lethaby A, Vollenhoven B, Sowter M. Efficacy of pre-operative gonadotrophin hormone releasing analogues for women with uterine fibroids undergoing hysterectomy or myomectomy: a systematic review. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2002;109:1097-1108.

Lijoi D, Ferrero S, Mistrangelo E, et al. Bowel preparation before laparoscopic gynaecological surgery in benign conditions using a 1-week low fibre diet: a surgeon blind, randomized and controlled trial. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2009;280:713-718.

Møller AM, Villebro N 2005 Interventions for pre-operative smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 3: CD002294.

Munro J, Booth A, Nicholl J. Routine pre-operative testing: a systematic review of the evidence. Health Technology Assessment. 1997;1(i–iv):1-62.

Muzzi L, Bellati F, Zullo MA, et al. Mechanical bowel preparation before gynaecologic laparoscopy: a randomized, single-blind controlled trial. Fertility and Sterility. 2006;85:689-693.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, developed by the National Collaborating Centre for Acute Care 2003 The Use of Routine Pre-operative Tests for Elective Surgery. NICE, London.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Clinical Guidance Clinical Guideline 46. Venous Thromboembolism: Reducing the Risk of Venous Thromboembolism (Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism) in Inpatients Undergoing Surgery. London: National Collaborating Centre for Acute Care; 2007.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Clinical Guideline 64. Prophylaxis Against Infective Endocarditis. Antimicrobial Prophylaxis Against Infective Endocarditis in Adults and Children Undergoing Interventional Procedures. London: NICE; 2008.

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Guideline Number 40. Venous Thromboembolism and Hormonal Contraception. London: RCOG; 2004.

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Consent Advice Number 4. Abdominal Hysterectomy for Heavy Periods. London: RCOG; 2004.

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Consent Advice Number 5. Pelvic Floor Repair and Vaginal Hysterectomy for Prolapse. London: RCOG; 2004.

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Clinical Governance Advice Number 6. Obtaining Valid Consent. London: RCOG; 2008.

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Consent Advice Number 1. Diagnostic Hysteroscopy Under General Anaesthesia. London: RCOG; 2008.

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Consent Advice Number 2. Laparoscopy. London: RCOG; 2008.

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Consent Advice Number 3. Laparoscopic Tubal Occlusion. London: RCOG; 2008.

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Guideline Number 104. Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Surgery. Edinburgh: SIGN; 2008.

Sowter MC, Lethaby A, Singala AA 2002 Pre-operative endometrial thinning agents before endometrial destruction for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2: CD001124.