CHAPTER 27 Premenstrual syndrome

Introduction

Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) refers to somatic and psychological symptoms which occur in relation to the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. Most women of reproductive age will have some symptoms related to the premenstrual phase of the cycle. These are usually very mild and are physiological. Only when the symptoms cause significant disruption to normal functioning are they considered to be PMS. The term ‘premenstrual dysphoric disorder’ (PMDD) is also used and this represents the severe, predominantly psychological form of PMS. It is estimated that 3–8% of women of reproductive age experience debilitating symptoms leading to functional or psychological impairment (Angst et al 2001, Wittchen et al 2002). PMS and PMDD can be debilitating conditions. The impact on society and women’s lives can be very high and comparable to major depressive disorder (Pearlstein et al 2000, Halbriech et al 2003).

Definition

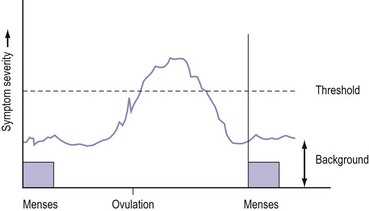

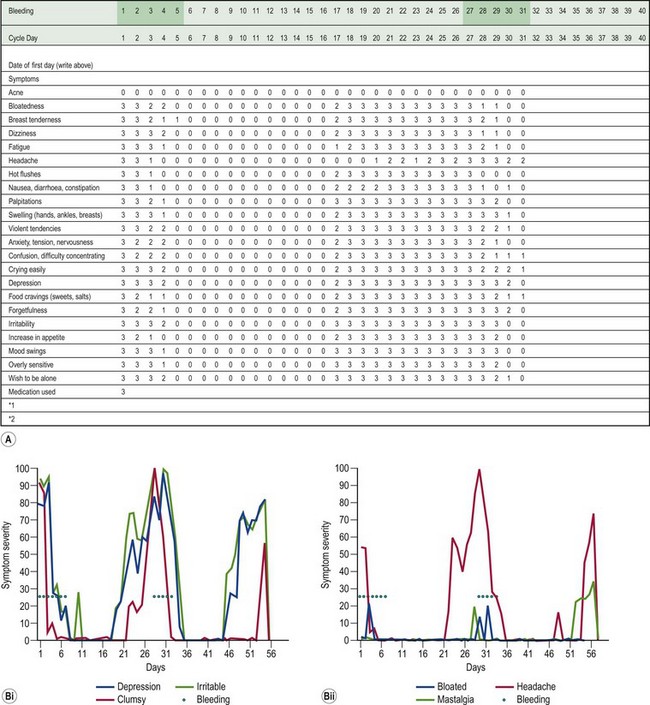

PMS is characterized by symptoms or clusters of symptoms that are associated with the premenstrual phase of the cycle, are recurrent, and are severe enough to cause impairment and distress (Halbriech et al 2007). Any symptom or cluster of symptoms qualify as PMS if they occur during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, are alleviated shortly following menses, and are not merely an exacerbation of other underlying conditions. PMDD has similar but separate criteria (Table 27.1, Figures 27.1 and 27.2)

| Type | Definition |

|---|---|

| Physiological premenstrual symptoms | Symptoms occur in the luteal phase of the cycle but are so mild that they are not troublesome. |

| Premenstrual syndrome | PMS symptoms leading up to menstruation and completely relieved by the end of menstruation. |

| Mild | Does not interfere with personal/social and professional life. |

| Moderate | Interferes with personal/social and professional life but still able to function and interact, maybe suboptimally. |

| Severe | Unable to interact personally/socially/professionally, withdraws from social and professional activities (treatment resistant). |

| Premenstrual dysphoric disorder | Currently considered as research criteria, not yet in general use outside the USA, but increasingly addressed in Europe and other countries. This definition of the severe psychological end of the PMS spectrum has been devised by the American Psychiatric Association. |

| Premenstrual exaggeration | Background psychopathology, physical, medical or other condition which worsens premenstrually with incomplete relief of symptoms when menstruation ends. |

| Misattribution | Underlying physical, psychological or psychiatric disorder wrongly labelled as PMS by general practitioner, nurse, gynaecologist, other specialist or patient. |

Adapted from Royal College Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Management of Premenstrual Syndrome. Green-top guidelines no. 48. London : RCOG, 2007. Available at: http://www.rcog.org.uk/womens-health/clinical-guidance/management-premenstrual-syndrome-green-top-48 (Accessed: Feb 2010).

Symptoms

A woman has PMS if she complains of psychological or somatic symptoms, or both, recurring specifically during the luteal phase of the cycle and resolving by the end of menstruation (Ismail and O’Brien 2005). This separates PMS from psychiatric disorders. The symptoms should be confirmed prospectively by daily ratings during the last two consecutive cycles. This prospective rating is best achieved using the Daily Record of Severity of Problems form (Table 27.2, Box 27.1).

Table 27.2 Commonly reported symptoms in women with premenstrual syndrome

| Psychological symptoms | Irritability, depression, crying/tearfulness, anxiety, tension, mood swings, lack of concentration, confusion, forgetfulness, unsociableness, restlessness, temper outbursts/anger, sadness/blues, loneliness. |

| Pain symptoms | Headache/migraine, breast tenderness/soreness/pain/swelling (collectively know as ‘premenstrual mastalgia’), back pain, abdominal cramps, general pain. |

| Bloatedness | Weight gain, abdominal bloating, oedema of extremities (arms and legs), abdominal swelling and water retention. |

| Appetite symptoms | Increased appetite, food cravings, nausea. |

| Behavioural symptoms | Fatigue, dizziness, sleep/insomnia, decreased efficiency, accident prone, sexual interest changes, increased energy, tiredness. |

Diagnostic criteria for premenstrual syndrome

An international multidisciplinary group of experts who evaluated the definitions of PMS/PMDD recommended the following diagnostic criteria (Halbriech et al 2007):

Aetiology and Pathophysiology

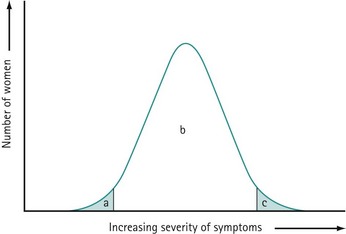

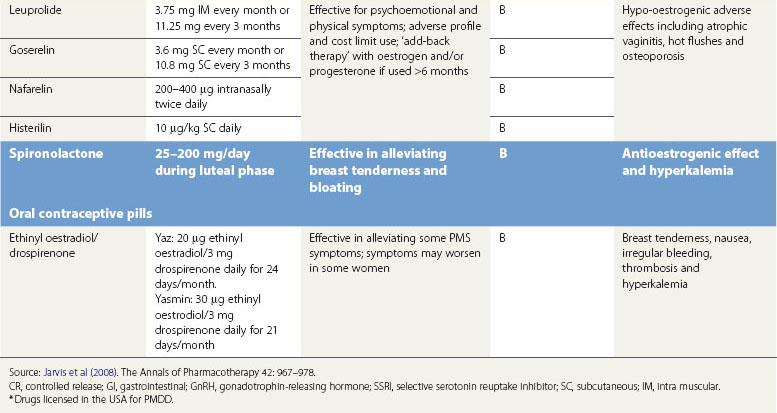

The precise aetiology of PMS/PMDD is unknown. Various theories have been suggested. The current evidence suggests the possibility that both ovarian hormonal and neuroendocrine factors contribute to PMS/PMDD. The majority of women of reproductive age experience mild symptoms which are not troublesome and do not interfere with their daily activities. This should be considered as physiological rather than pathological (Figure 27.3).

Figure 27.3 Aetiological theories which have been proposed for premenstrual syndrome/premenstrual dysphoric disorder.

Ovarian hormones

PMS only occurs in women of reproductive age during the luteal phase of the cycle; symptoms classically disappear when ovulation is absent. PMS is absent before puberty, during pregnancy and following the menopause. Suppression of ovulation with gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues (Hussain et al 1992) or following bilateral oophorectomy typically eliminates the symptoms. Conversely, postmenopausal women on sequential combined hormone replacement therapy can redevelop PMS-/PMDD-like symptoms during the progestogen phase of therapy (Hammarback et al 1985).

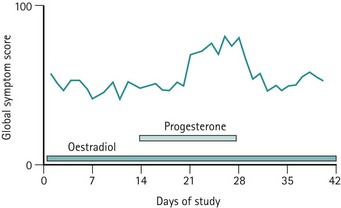

Previously, it was believed that hormonal or progesterone imbalances during ovulatory cycles may trigger the symptoms. However, administration of progesterone during this phase does not abolish symptoms (Wyatt et al 2001), and differences in oestrogen or progesterone levels have not been demonstrated between PMS patients and asymptomatic controls. Alternative hypotheses include the proposal that symptoms may be triggered by a preovulatory peak in oestradiol level or a postovulatory increase in progesterone level (Magos et al 1986, Schmidt et al 1998). These hypotheses do not explain why some women only develop symptoms in the late luteal phase.

As there is no clear evidence to implicate different levels of oestrogen or progesterone in inducing PMS, an attractive and convincing theory, partially supported by good evidence, is that an enhanced responsiveness or sensitivity exists to normal levels of these fluctuating hormones (Yonkers et al 2008) (Figures 27.4 and 27.5).

Serotonergic system

Studies undertaken on the rat model demonstrate that serotonin receptor concentrations vary with changes in oestrogen and progesterone levels (Biegen et al 1980). Serotonin depletion affects the sex-steroid-dependent behaviour; this suggests that the role of serotonin is to modulate behavioural changes by interacting with serotonin transmission, which has been demonstrated in studies performed on rodents (Carlsson and Carlsson 1988, Rubinow et al 1998) and non-human primates (Bethea et al 2002).

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin receptor agonists (Landén et al 2001), serotonin precursors (Steinberg et al 1999) and serotonin-enhancing agents effectively dampen premenstrual symptoms. Impairment of serotonin transmission by serotonin receptor antagonists (Roca et al 2002) or a tryptophan-free diet provokes symptoms (Menkes et al 1994). Women with PMS have a low platelet concentration of serotonin and this concentration varies during the menstrual cycle (Ashby et al 1998). This suggests that serotonin may play an important role in the pathophysiology of PMS/PMDD.

There is limited research on the genetics of serotonin in PMDD, but there does appear to be a difference in specific serotonin receptor polymorphism in PMDD sufferers (Dhingra et al 2007).

The GABAergic system

The GABA transmitter is a major inhibitory system in the central nervous system. GABA levels are low in the plasma and cerebrospinal fluid of individuals with mood disorders (Brambilla et al 2003). GABA levels have also been found to be decreased in women with PMDD during the late luteal phase compared with normal women whose plasma levels increase from the midfollicular phase (Halbriech et al 1996).

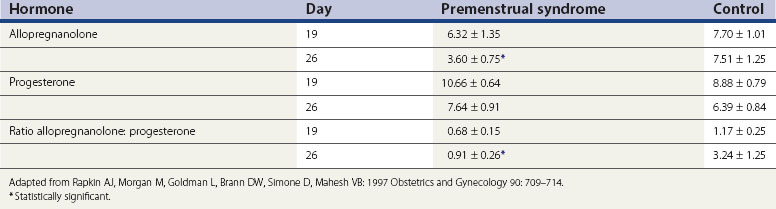

Allopregnanolone is a metabolite of progesterone, and levels vary in parallel with progesterone levels during the menstrual cycle (Genazzani et al 1998). In women with PMS, allopregnanolone levels are low in the follicular and luteal phases (Rapkin et al 1997, Bicíková et al 1998). Allopregnanolone is a positive modulator of the GABA receptor and a potent neurotransmitter with effects on mood, behaviour and cognitive function. Allopregnanolone has a bimodal effect on mood symptoms similar to benzodiazepines, barbiturates and alcohol. However, in some women with PMS, the plasma levels of allopregnanolone are low, suggesting that GABA receptor dysfunction might play a role in these women (Girdler et al 2001) (Table 27.3).

Theories related to sodium and fluid retention

Women with PMS report various somatic symptoms in the form of breast tenderness, bloating and swelling. Studies have failed to demonstrate weight gain, changes in abdominal dimensions, or any true water or sodium retention, even in women who experience bloatedness (Faratian et al 1984). There is no evidence to suggest that a shift in premenstrual water and electrolytes occurs; this is paralleled by a lack of similar changes in the hormones which influence potassium and water transport, such as components of atrial natriuretic peptide and the renin–angiotensin system. Studies have consistently shown that evidence is lacking to support this hypothesis.

Prolactin

Box 27.2 Differential diagnoses of PMS

Psychiatric disorders

Other causes of breast symptoms

Other causes of abdominal bloatedness and water retention

Non-Pharmacological Treatments

Lifestyle modifications

In women with mild-to-moderate symptoms, lifestyle modifications including dietary changes, exercise and cognitive behavioural therapies (CBT) may be enough to improve the symptoms. Dietary modifications in the form of reduced intake of caffeine, salt and refined sugars, a low glycaemic index diet and smaller meals may improve irritability, insomnia, fluid retention, breast tenderness, bloating and weight gain (Rapkin 2003, Kaur et al 2004). Increased intake of complex carbohydrates in the form of drink supplements decreases mood changes; this may be due to an increase in tryptophan, a precursor to serotonin (Sayegh et al 1995, Rapkin 2003). Exercise significantly improves mood and lethargy by increasing the release of endorphins (Aganoff and Boyle 1994). However, the evidence is quite limited for the effectiveness of most of these interventions.

Psychological interventions

In one series, women were offered eight sessions of CBT resulting in good outcomes (Slade 1989). Treatment was focused on identification of triggers and stresses associated with negative emotions, problem solving, relaxation and CBT to clarify attributions to the symptoms. Relaxation therapy was found to be superior to daily PMS symptom monitoring alone, or taking time out to read, in terms of comparative symptomatic approach (Goodale et al 1990). CBT combined with lifestyle changes is more effective in improving mood and PMS symptoms (Christensen AP et al 1995).

One randomized trial compared 10 sessions of CBT with SSRI (fluoxetine 20 mg/day) and both combined (Hunter et al 2002). There was significant improvement in all groups of symptom measures and the percentage of women fulfilling the PMDD criteria post treatment. Both treatments were equally effective at the end of 6 months; however, 1-year follow-up revealed that women who had undergone CBT maintained the improvement compared with women who had been on fluoxetine. Women with depressed mood responded poorly to both treatments, but learning active behavioural coping strategies had a good outcome at 1-year follow-up.

Vitamin or non-medical approaches

Vitamin B6 and pyridoxine

There are no well-designed randomized controlled studies to support the recommendation of any form of vitamin or herbal supplementation. A systematic review of five randomized controlled studies and one intervention study showed limited evidence for vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) supplementation in inadequate studies (Williams et al 2005). Pyridoxine 50–100 mg/day may improve premenstrual depressive symptoms provided that prescribed, daily doses do not exceed 100 mg to avoid the risk of peripheral neuropathy. Due to the poor quality of studies, pyridoxine alone cannot be recommended for treatment, although vitamin B6 and pyridoxine may have some benefit as an adjunct to treat depressive symptoms (pyridoxine is a cofactor necessary for the metabolic conversion of tryptophan to neuropeptides such as serotonin).

Calcium

In a single study, calcium supplementation 600 mg twice daily during the luteal phase of the cycle was shown to reduce emotional and physical symptoms of PMS/PMDD by the second or third treatment cycle (Thys-Jacobs et al 1998).

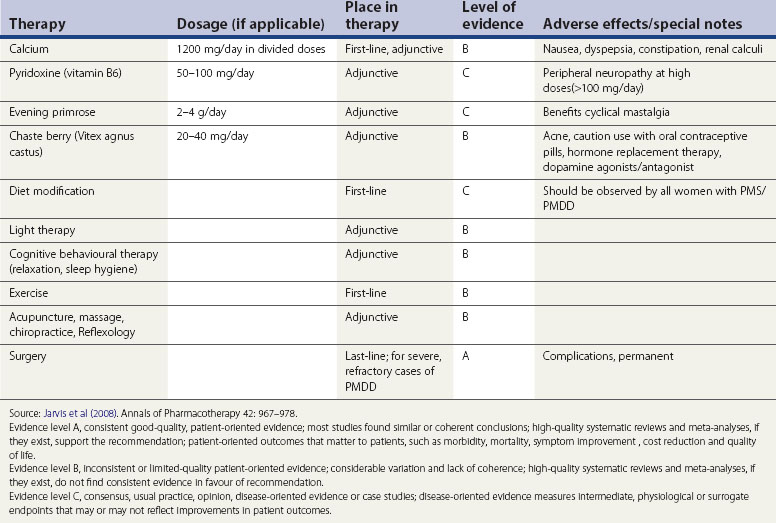

Alternative therapy

Various treatments in the form of massage, biofeedback, acupuncture and reflexology have been proposed but none of these have been proven to be effective. Double-blind randomized and crossover studies for light therapy did not provide conclusive evidence, and there are safety issues to be taken into account before embarking on this form of treatment (Lam et al 1999) (Table 27.4)

Pharmacological Treatments

Progesterone

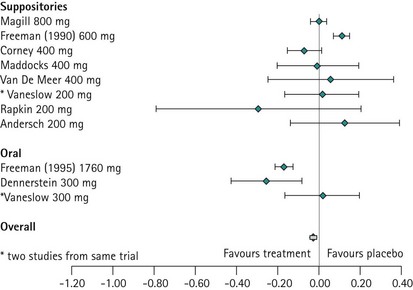

The evidence from the meta-analysis and systematic review of 10 randomized controlled trials clearly demonstrates that progesterone is not effective in treating PMS (Wyatt et al 2001). This is not surprising when one considers that progesterone deficiency has never been demonstrated in women with PMS, and when it is appreciated that the administration of sequential hormone replacement therapy to postmenopausal women commonly results in the development of mood changes similar to PMS during the progesterone phase of therapy (Hammarback et al 1985). Progesterone is not recommended in the management of PMS, although progesterone and progestogens are the only licensed products for the management of PMS in the UK (Figure 27.7).

Oestrogen

Oestrogen is effective at suppressing ovulation at doses of 100–200 µg (transdermal patches) (Smith et al 1995, Watson et al 1989). As unopposed oestrogen can cause endometrial hyperplasia and carcinoma, cyclical progestogen should also be administered (Paterson ME et al 1980). Progesterone administration can induce PMS symptoms, thereby limiting the efficacy of oestrogen. In women who are intolerant to cyclical progesterone, a shorter duration of 7 days is adequate to prevent endometrial hyperplasia (Studd 2008). A simple regimen is for progestogen to be administered on the first 7 days of each calendar month. A withdrawal bleed occurs on approximately the 10th day of the calendar month.

In women who are intolerant to oral progestogen or who have irregular or heavy bleeding, the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system will usually be beneficial, providing endometrial protection and possibly amenorrhoea without producing PMS-like side-effects (Sitruk-Ware 2007). In some women, levonorgestrel can be absorbed systemically in the first months of therapy until the endometrium becomes atrophic. This is to be expected, and doctors and patients need to be forewarned, particularly of its transient nature.

Oral contraceptive pills

Newer OCPs contain the progestin drospirenone. This is a derivative of spironolactone and has similar antimineralocorticoid and antiandrogenic properties. A systematic review of all randomized controlled trials comparing the combined OCPs containing drospirenone with a placebo or other OCPs for their effect on PMS concluded that drospirenone 3 mg plus ethinyl oestradiol 20 µg may help to treat PMS in women with PMDD (Lopez et al 2008). The drospirenone group had a greater decrease in impairment of productivity, social activities and relationships. Little effect was found on less severe symptoms when comparing drospirenone plus oestrogen with another combined oral contraceptive. A 6-month study showed fewer symptoms with drosiprenone, while a 2-year trial found the groups to be similar. Two OCPs, Yaz and Yasmin, containing drospirenone have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of PMDD but are not approved in Europe or the UK. FDA approval gives the manufacturer permission to make claims about the effectiveness of these OCPs for ‘treating PMDD in women who require oral contraception’. It highlights the fact that the effectiveness beyond three cycles is unknown.

Danazol

Danazol has been shown to be effective when ovulation is suppressed. However, there are concerns about masculinizing side-effects. At a reduced dose (200 mg) in the luteal phase, danazol has been shown to be effective for cyclical mastalgia but not other symptoms (O’Brien and Abukhalil 1999).

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists

GnRH agonist analogues are the synthetic analogues of naturally occurring GnRH. When administered, they reduce the secretion of luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone, thereby causing anovulation with associated hypo-oestrogenization. GnRH agonists are effective in treating psychological, emotional and physical symptoms associated with ovarian steroid cycles (Brown et al 1994, Freeman et al 1997, Mezrow et al 1994).

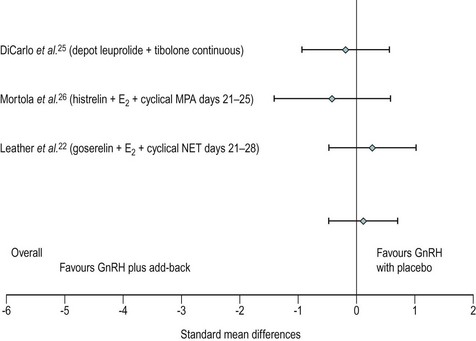

Many women do not tolerate the adverse effects, which are in the form of menopausal symptoms including flushes, insomnia, depression, headache and muscle aches. GnRH treatment should normally be limited to no more than 6 months to reduce the risk of reduction in bone mass. There is a likelihood of return of symptoms once the treatment is discontinued. In such women, the duration of therapy may be extended in certain circumstances by the addition of ‘add-back’ therapy which may be achieved using continuous daily conjugated oestrogen at a dose of 0.625 mg, oestradiol valerate 2 mg or transdermal oestradiol patches 50 µg along with progestogens such as medroxyprogesterone 5–10 mg. ‘Add-back’ with tibolone is also very useful (Leather et al 1999, Pickersgill 1998). In the small number of women requiring such long-term therapy, bone mineral density evaluation is required and advice on adequate calcium intake should be given (Figure 27.8).

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

Serotonergic neurotransmission plays an important role in the aetiology of PMS/PMDD. Serotonergic antidepressants, particularly SSRIs, have been demonstrated in several placebo-controlled studies to be significantly effective. SSRIs improve emotional and physical symptoms of PMDD, enhance psychosocial function and work performance, and improve quality of life (Pearlstein et al 2000, Wyatt et al 2002, Steiner et al 2006).

SSRIs can be administered using continuous, intermittent, semi-intermittent or symptom-onset strategies. Women with an irregular menstrual cycle or those who experience intolerable symptoms on discontinuation of treatment will benefit from a continuous daily SSRI dosing regimen. The continuous regimen may also help to improve somatic symptoms associated with PMDD in the long term (Luisi and Pawasauskas 2003).

SSRIs are well tolerated in the doses used for the treatment of PMDD. Headache, fatigue, insomnia, anxiety and sexual dysfunction are common symptoms associated with the continuous dose regimen (Wyatt et al 2004).

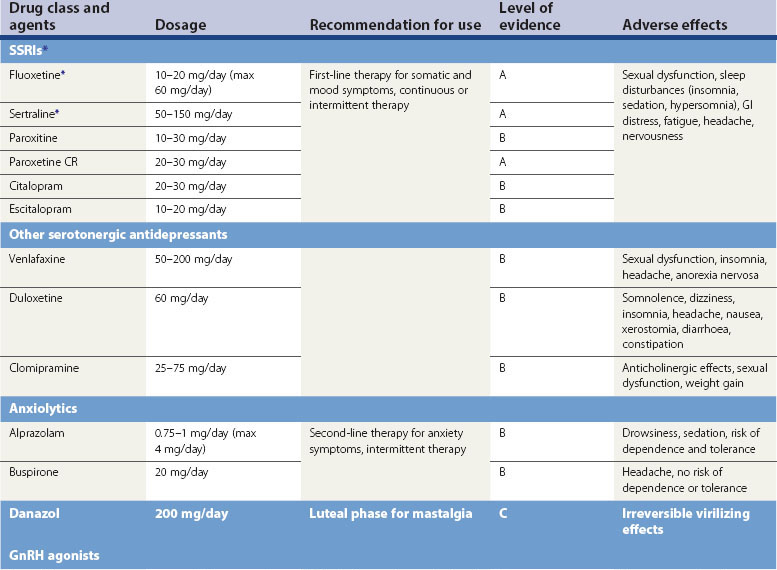

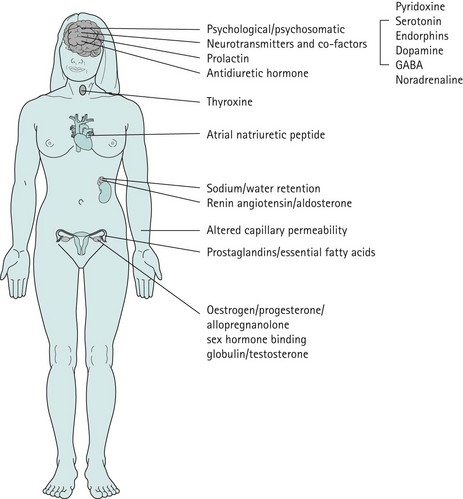

The US FDA has licensed various SSRIs for PMDD, but they are not licensed in the UK or Europe (Table 27.5).

Other antidepressants

Clomipramine, a tricyclic antidepressant with strong serotonergic activity, may be effective in treating severe PMDD (Sundblad et al 1993). Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, venlafaxine and duloxetine have been found to be more effective than placebo for the treatment of PMDD (Mazza et al 2008).

Spironolactone

Spironolactone, a potassium-sparing diuretic and aldosterone receptor antagonist, exhibits antimineralocorticoid and antiandrogenic effects and interferes with synthesis of testosterone (Wang et al 1995, Burnet et al 1991). At doses of 25–200 mg/day during the luteal phase, spironolactone can alleviate symptoms of weight gain, bloating and breast tenderness, and may also decrease negative mood and somatic scores despite the fact that there is no evidence of water retention.

Anxiolytic agents

Anxiety is common in PMS/PMDD; anxiolytic agents during the luteal phase of the cycle can be helpful in women with persistent anxiety despite treatment with SSRIs. Alprazolam at a dose of 0.25 mg three to four times per day during the luteal phase has been shown to be effective in double-blind, placebo-controlled trials for the treatment of premenstrual depression, irritability, hostility and social withdrawal (Berger and Presser 1994, Freeman et al 1995).

Surgery

In a small group of women who have not responded or are not able to tolerate the various medical treatments or combinations of medical treatment, surgical management in the form of hysterectomy with bilateral oopherectomy or bilateral removal of ovaries may be considered (Cronje et al 2004). Obviously, randomized trials are not possible in this form of treatment, but in open studies, 95% of carefully selected women who underwent bilateral oophorectomy and hysterectomy were shown to be very satisfied 4 years after surgery (Cronje et al 2004). These women require long-term hormone replacement therapy in the form of oestradiol; in these circumstances, it is unnecessary to give progestogen. No placebo-controlled studies have been published specifically to demonstrate the efficacy of bilateral oophorectomy alone for the management of PMS/PMDD. When bilateral oophorectomy is contemplated (with or without hysterectomy), most gynaecologists consider that a trial of a GnRH analogue for three cycles is advisable to demonstrate the potential efficacy of what is a very invasive procedure.

Conclusion

KEY POINTS

Aganoff JA, Boyle GJ. Aerobic exercise, mood status and menstrual cycle symptoms. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1994;38:183-192.

Andersch B. Bromocriptine and premenstrual symptoms: a survey of double blind trials. Obstetrical and Gynaecological Survey. 1983;38:643-646.

Angst J, Sellaro R, Merikangas KR, Endicott J. The epidemiology of premenstrual psychological symptoms. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2001;104:110-116.

Ashby CRJr, Carr LA, Cook CL, Steptoe MM, Franks DD. Alteration of platelet serotoninergic mechanism and monoamine oxidase activity in premenstrual syndrome. Biological Psychiatry. 1998;24:225-233.

Berger CP, Presser B. Alprazolam in the treatment of two subsamples of patients with late luteal phase dysphoric disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1994;84:379-385.

Bethea CL, Lu NZ, Gundlah C, Streicher JM. Diverse actions of ovarian steroids in the serotonin neural systems. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 2002;23:41-100.

Bicíková M, Dibbelt L, Hill M, Hampl R, Stárka L. Allopregnanolone in women with premenstrual syndrome. Hormone and Metabolic. Research. 1998;30:227-230.

Biegen A, Bercovtz H, Samuel D. Serotonin receptor concentration during the oestrous cycle of the rat. Brain Research1. 1980;87:221-225.

Brambilla P, Perez J, Barale F, Schettini G, Soares JC. GABAergic dysfunction in mood disorders. Molecular Psychiatry. 2003;8:721-731.

Brown CS, Ling FW, Andersen RN, Farmer RG, Arheart KL. Efficacy of depot leuprolide in premenstrual syndrome: effect of severity and type in controlled trial. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1994;84:779-786.

Burnet RB, Radden HS, Easterbrook EG, McKinnon RA. Premenstrual syndrome and spironolactone. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1991;31:366-368.

Carlsson M, Carlsson A. A regional study of sex differences in rat brain serotonin. Progress in Neuropsychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 1988;12:53-61.

Casper RF, Hearn MT. The effect of hysterectomy and bilateral oophorectomy in women with severe premenstrual syndrome. American Journal of Obstet rics and Gynecology. 1990;162:105-109.

Christensen AP, Oei TPS. The efficacy of cognitive behaviour therapy in treating premenstrual dysphoric changes. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1995;33:57-63.

Cronje WH, Vashisht A, Studd JW. Hysterectomy and bilateral oophorectomy for severe premenstrual syndrome. Human Reproduction. 2004;19:2152-2155.

Dhingra V, Magnay JL, O’Brien PM, Chapman G, Fryer AA, Ismail KM. Serotonin receptor 1A C (-1019) G polymorphism associated with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2007;110:788-792.

Douglas S. Premenstrual syndrome. Evidence-based treatment in family practice. Canadian Family Physician. 2002;48:1789-1797.

Endicott J, Harrison W. Daily Record of Severity of Problems Form. Department of Research Assessment and Training. New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1990.

Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W. Daily Record of Severity of Problems: reliability and validity. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2006;9:41-49.

Faratian B, Gaspar A, O’Brien PM, Johnson IR, Filshie GM, Prescott P. Premenstrual syndrome: weight, abdominal size and perceived body image. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1984;50:200-204.

Freeman EW, Rickels K, Sondheimer SJ, et al. A double-blind trial of oral progesterone, alprazolam and placebo in treatment of severe premenstrual syndrome. Journal American Medical Assocication. 1995;274:51-57.

Freeman EW, Sondheimer SJ, Rickels K. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist in the treatment of premenstrual symptoms with and without ongoing dysphoria: a controlled study. Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1997;33:303-309.

Genazzani AR, Petraglia FL, Bernardi F, et al. Circulating levels of allopregnanolone levels in humans: gender, age and endocrine influences. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1998;83:2099-2103.

Girdler SS, Straneva PA, Light KC, Pedersen CA, Morrow AL. Allopregnanolone levels and reactivity to mental stress in premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2001;49:788-797.

Goldberg AP, Miller B. A scaled version of the general health questionnaire. Psychological Medicine. 1979;9:139-145.

Goodale IL, Domar AD, Benson H. Alleviation of premenstrual syndrome with the relaxation response. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1990;75:649-655.

Halbreich U, Petty F, Yonkers K, Kramer GL, Rush AJ, Bibi KW. Low plasma gamma-aminobutyric levels during the late luteal phase of women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;152:718-720.

Halbriech U, Borenstein J, Pearlstein T, Kahn LS. The prevalence, impairment, impact and burden of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMS/PMDD). Psychoendocrinology. 2003;28:1-23.

Halbriech U, Backstorm T, Eriksson E, et al. Clinical diagnostic criteria for premenstrual syndrome and guidelines for their quantification for research studies. Gynecological Endocrinology. 2007;23:123-130.

Hammarback S, Backstrom T, Hoist J, et al. Cyclical mood changes as in the premenstrual tension syndrome using sequential oestrogen — progestagen postmenopausal replacement therapy. Acta Obstetrica of Gynaecologica Scandinavica. 1985;64:393-397.

Harrison WM, Endicott J, Nee J. Treatment of premenstrual dysphoria with alprazolam: a controlled study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1990;47:270-275.

Henshaw C, O’Brien PMS, Foreman A, et al. An experimental model for PMS. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1993;25:713-719.

Hunter MS, Ussher J, Browne S, et al. Medical (fluoxetine) and psychological (cognitive behavioural therapy) treatments for premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD): a study of treatment processes. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2002;53:811-818.

Hussain SY, Massil JH, Matta WH, Shaw RW, O’Brien PM. Buserelin in premenstrual syndrome. Gynecological Endocrinology. 1992;6:57-64.

Ismail K, O’Brien S. Premenstrual syndrome. Current Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2005;15:25-30.

Jarvis CI, Lynch AM, Morin AK. Management strategies for premenstrual syndrome/premenstrual dysphoric disorder. The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 2008;42:967-978.

Kaur G, Gonsalves L, Thacker HL. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder: a review for the treating practitioner. Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 2004;71:303-305.

Khastgir G, Studd J, Holland N, Alaghband-Zadeh J, Sims TJ, Bailey AJ. Anabolic effect of long term oestrogen replacement on bone collagen in elderly postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Osteoporosis International. 2001;12:456-470.

Lam RW, Carter D, Misri S, Kuan AJ, Yatham LN, Zis AP. A controlled study of light therapy in women with late luteal phase dysphoric disorder. Psychiatry Research. 1999;86:185-192.

Landén M, Eriksson O, Sundblad C, Andersch B, Naessén T, Eriksson E. Compounds with affinity for serotonergic receptors in the treatment of premenstrual dysphoria: a comparison of buspirone, nefazodone and placebo. Psychopharmacology. 2001;155:292-298.

Leather AT, Studd JW, Watson NR, Holland EF. The treatment of severe premenstrual syndrome with goserelin with and without ‘add-back’ oestrogen therapy: a placebo controlled study. Gynecological. Endocrinology. 1999;13:48-55.

Lopez LM, Kaptein A, Helmerhorst FM 2008 Oral contraceptives containing drospirenone for premenstrual syndrome. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 1: CD006586.

Luisi AF, Pawasauskas JE. Treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23:1131-1140.

Magos AL, Brewster E, Singh R, O’Dowd T, Brincat M, Studd JW. The effects of norethisterone in postmenopausal women on oestrogen replacement therapy: a model for the premenstrual syndrome. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1986;93:1290-1296.

Mazza M, Harnic D, Catalano V, Janiri L, Bria P. Duloxetine for premenstrual dysphoric disorder: a pilot study. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 2008;9:517-521.

Menkes DB, Coates LA, Fawcett JB. Acute tryptophan depletion aggravates premenstrual syndrome. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1994;32:37-44.

Mezrow G, Shoupe D, Spicer D, Lobo R, Leung B, Pike M. Depot leuprolide acetate with oestrogen and progestin add-back for long-term treatment of premenstrual syndrome. Fertility and Sterility. 1994;62:932-937.

O’Brien PM, Abukhalil IE. Randomised controlled trial of management of premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual mastalgia using luteal phase only danazol. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1999;180:18-23.

Paterson ME, Wade-Evans T, Sturdee DW, Thom MH, Studd JW. Endometrial disease after treatment with oestrogens and progestogens in the climactric. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 1980;280:822-824.

Pearlstein TB, Halbriech U, Batzed ED, et al. Psychosocial functioning in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder before and after treatment with sertraline or placebo. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2000;61:101-109.

Pickersgill A. GnRH agonist and add-back therapy: is there a perfect combination? BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1998;105:475-485.

Rapkin A. A review of treatment of premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2003;28(Suppl):39-53.

Rapkin AJ, Morgan M, Goldman L, Brann DW, Simone D, Mahesh VB. Progesterone metabolite allopregnanolone in women with premenstrual syndrome. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1997;90:709-714.

Roca CA, Schmidt PJ, Smith MJ, Danaceau MA, Murphy DL, Rubinow DR. Effects of metergoline on symptoms in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:1876-1881.

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Management of Premenstrual Syndrome. Green-top Guidelines No. 48. London: RCOG; 2007. Available at www.rcog.org.uk/resources/public/pdf/green_top48_pms.pdf

Rubinow DR, Schmidt PJ, Roca CA. Oestrogen serotonin interactions: implications for affective regulation. Biological Psychiatry. 1998;44:839-850.

Sayegh R, Schiff I, Wurtman J, Spiers P, McDermott J, Wurtman R. The effect of carbohydrate rich beverage on mood, appetite and cognitive function in women with premenstrual syndrome. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1995;86:520-528.

Schellenberg R. Treatment for the premenstrual syndrome with agnus castus fruit extract: prospective, randomised, placebo controlled study. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 2001;322:134-137.

Schmidt PJ, Nieman LK, Danaceau MA, Adams LF, Rubinow DR. Differential behavioral effects of gonadal steroids in women with and those without premenstrual syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine. 1998;338:209-216.

Sitruk-Ware R. The levonorgestrel intrauterine system for use of in peri- and postmenopausal women. Contraception. 2007;7(Supplement):S155-S160.

Slade P. Psychological therapy for premenstrual symptoms. Behavioural Psychotherapy. 1989;17:135-150.

Smith RN, Studd JW, Zamblera D, Holland EF. A randomised comparison over 8 months of 100 micrograms and 200 micrograms twice-weekly doses of transdermal oestradiol in the treatment of premenstrual syndrome. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1995;102:475-484.

Steinberg S, Annable L, Young S, Liyanage N. A placebo controlled trial of L-tryptophan in premenstrual dysphoria. Biological Psychiatry. 1999;45:313-320.

Steiner M, Brown E, Trzepacz P, et al. Fluoxetine improves functional work capacity in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2003;6:71-77.

Steiner M, Pearlstein T, Cohen LS, et al. Expert guidelines for the treatment of severe PMS, PMDD, and comorbidities: the role of SSRIs. Journal of Women’s Health. 2006;15:57-69.

Studd J. Suppression of cyclical ovarian function in the treatment of severe premenstrual syndrome/premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Gynaecology Forum. 2008;13:15-17.

Sundblad C, Hedberg MA, Eriksson E. Clomipramine administered during the luteal phase reduces the symptoms of premenstrual syndrome: a placebo-controlled trial. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1993;9:133-145.

Thys-Jacobs S, Starkey P, Bernstein D, Tian J. Calcium carbonate and the premenstrual syndrome: effects on premenstrual and menstrual symptoms. Premenstrual Syndrome Study Group. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1998;179:444-452.

Wang M, Hammarback S, Lindhe BA, Backstrom T. Treatment of premenstrual syndrome by spironolactone: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 1995;74:803-808.

Watson NR, Studd JW, Savvas M, Garnett T, Baber RJ. Treatment of severe premenstrual syndrome with oestradiol patches and cyclical oral norethisterone. The Lancet. 1989;2:730-732.

Williams AL, Cotter A, Sabina A, et al. The role of vitamin B-6 as treatment for depression: a systematic review. Family Practitioner. 2005;22:532-537.

Wittchen HU, Becker E, Lieb R, Krause P. Prevalence, incidence and stability of premenstrual dysphoric disorder in the community. Psychological Medicine. 2002;32:119-132.

Wyatt K, Dimmock P, Jones P, Obhrai M, O’Brien S. Efficacy of progesterone and progestogens in premenstrual syndrome: systematic review. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 2001;323:776-781.

Wyatt KM, Dimmock PW, Ismail KM, Jones PW, O’Brien PM. The effectiveness of GnRHa with and without add-back therapy in treating premenstrual syndrome: a meta analysis. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2004;111:585-593.

Yonkers KA, O’Brien PMS, Eriksson E. Premenstrual syndrome. The Lancet. 2008;371:1200-1210.