14

Premenstrual syndrome

Introduction

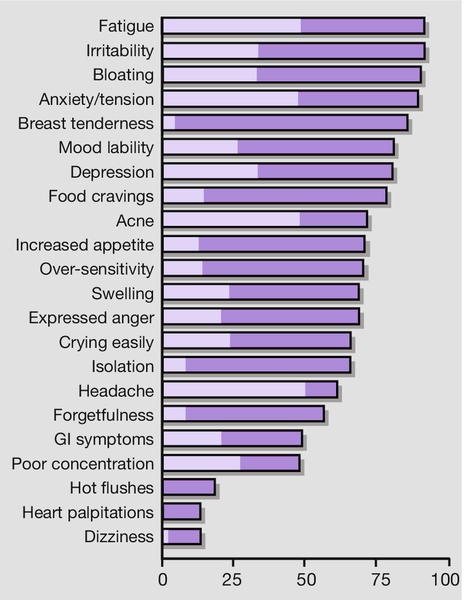

Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) can usefully be defined as ‘a condition manifesting with physical, behavioural and psychological symptoms in the absence of organic or psychiatric disease, which regularly occurs during the luteal phase of each ovarian cycle and which disappears or significantly regresses by the end of menstruation’. PMS is considered severe if it impairs work, relationships or usual activities. Some observers note that as many as 95% of women suffer mild symptoms, and between 5% and 10% of women have symptoms severe enough to disrupt their lives, principally in the 2 weeks leading up to the start of menstruation.

Over 150 symptoms have been attributed to PMS, but particularly:

![]() mood changes/irritability

mood changes/irritability

![]() abdominal bloatedness

abdominal bloatedness

![]() breast tenderness (cyclical mastalgia)

breast tenderness (cyclical mastalgia)

![]() headaches

headaches

![]() oedema.

oedema.

Aetiology

The aetiology of PMS remains largely unknown. Ovulatory cycles are generally considered to be a necessary prerequisite. Many hypotheses have considered whether there might be abnormal levels of specific hormones, and research has focused on progesterone, oestrogen, adrenocorticotrophic hormone, vasopressin, luteinizing hormone, prolactin and thyroid-stimulating hormone. There is no consistent evidence that any of these are abnormal in PMS, but there are suggestions that it is the changing patterns of hormone levels, rather than the absolute levels, which is important. There may be an abnormality in levels of neurotransmitter function, particularly serotonin, and this is discussed further under ‘Management’, below.

Clinical presentation

As there are no specific biochemical tests for PMS, the diagnosis is dependent on a prospective charting of symptoms to confirm that there is a true exacerbation in the luteal phase when compared with the follicular phase of the cycle (Fig. 14.1). A simple calendar record of the presence or absence of a woman’s three principal symptoms and days of menstruation is appropriate. There are numerous specific criteria; many of them research tools which are not necessarily always applied strictly to clinical practice. An example of one of these is shown in Box 14.1.

GI, gastrointestinal.

Differential diagnosis

Symptoms that can be worse in the follicular phase are not attributable to PMS. Other conditions such as endometriosis, migraine headaches, depression and anxiety disorders are exacerbated premenstrually, but again should not be confused with the more specific diagnosis of PMS. Perimenopausal mood changes are usually non-cyclical and in these circumstances a serum follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) measurement should be considered. A normal FSH level does not exclude the menopause, but the investigation may be of particular value in those who have had a hysterectomy with ovarian conservation (since there is no menstruation), or those who have a levonorgestrel intrauterine system in situ.

The breast pain of PMS is usually cyclical, bilateral and poorly localized, and ‘lumpiness’ is common. By contrast, non-cyclical breast pain is precisely localized and rarely bilateral.

In those with abdominal swelling, it is important to consider intra-abdominal pathology such as ovarian cysts or ascites. The abdominal bloating of PMS is rapidly relieved by the onset of menstruation, perhaps owing to the relaxing effect of progesterone on smooth muscle or to comparative stasis of the gut in response to morphine-like endorphins. Hypothyroidism and anaemia should be considered in those complaining predominantly of fatigue. The characteristics of endogenous depression are different to those of the mood changes and irritability commonly observed in PMS, but, since both conditions are relatively common, it is not unusual to encounter both in the same woman.

Management

Women with mild PMS do not usually need medical treatment and may be helped by reassurance and information. General health measures such as improved diet with a low glycaemic index, increased exercise, self-relaxation, and reducing smoking and drinking might be helpful. Some women find self-help groups supportive, while others choose yoga or hypnosis. Treatment can be aimed at the symptoms, or at a hypothesized underlying cause.

Symptomatic treatment

A number of symptomatic treatments are in use, although the evidence supporting their effectiveness is limited. Those with premenstrual bloatedness can be treated in the same way as those with irritable bowel syndrome, and those with oedema may respond to a diuretic. Breast tenderness can also be treated with diuretics, as well as with bromocriptine or low-dose danazol. Mood changes are considered in more detail below.

Treatment aimed at the hypothesized underlying cause

A wide variety of medical treatments have been considered, many of which are still in current use. Close scrutiny, however, reveals that only a limited number of these are of proven value, and the treatment modalities are classified this way in Box 14.2. The ‘probably effective’ group consists of treatments demonstrated to be effective by good-sized trials, usually randomized placebo-controlled trials. The use of a placebo arm is particularly important in PMS research, as most placebo treatments demonstrate symptom improvements of around 30%. Treatments classified as ‘probably not effective’ have also been examined in well-conducted studies, and no significant benefit has been demonstrated over placebo. The ‘may be effective’ group includes therapies in which studies have been inconclusive, often because of small patient numbers. The three groups will be considered in more detail below.

Probably not effective

Progesterone or progestogens

The rationale for the use of progesterone or progestogens in the management of PMS is based on the unsubstantiated premise that there is a progesterone deficiency. Although initial data suggest there to be abnormal concentrations of metabolites of progesterone (pregnenolone and allopregnenolone), there is no consistent evidence that low concentrations of progesterone are found in women with PMS; overviews of randomized trials do not suggest any useful clinical benefit. However, intramuscular depot progestogen may be helpful due to its anovulatory effect (see later).

Evening primrose oil

The hypothesis is that there is a deficiency in essential fatty acids, particularly gamolenic acid, leading to low levels of prostaglandin E1 and therefore premenstrual symptoms. Evening primrose oil contains essential fatty acids, including gamolenic acid, and is available in many countries without a prescription. It is heavily promoted as an effective treatment for a range of conditions, including PMS, and it appears to have minimal side-effects. Trials demonstrate marginal, if any, clinical improvement, principally in the relief of mastalgia.

May be effective

Diet

The usual recommendations are for a reduction in salt, sugar, alcohol and caffeine, and an increase in meals with a low glycaemic index. It is suggested that an increased carbohydrate intake increases serotonergic activity, which in turn improves symptoms.

Exercise

Aerobic activity leads to increased endorphin levels, which are recognized to improve mood, and several studies suggest there may be some benefit in the treatment of PMS.

Psychological approach

Techniques aimed at reducing stress may be beneficial. Cognitive behavioural therapy, which encourages relaxation, and the use of ‘coping skills’ may also be helpful. A clinical psychology service should ideally be made available to women with severe disease.

Complementary therapy

Studies have explored the use of homeopathy, dietary supplementation, relaxation, massage, reflexology, chiropractic therapy and biofeedback. While there were some positive findings, there is no compelling evidence to support any of these therapies. Agnus Castus may be of benefit, but there is no standard quality-controlled preparation available. St John’s Wort has the potential for significant interaction with conventional medicines, including SSRIs and hormonal contraception. Despite the lack of an evidence base, these complementary therapies should be discussed as possible treatment options as part of an integrated treatment plan.

Vitamin B6 (pyridoxine)

It has been suggested that treatment with pyridoxine, the active form of which is a coenzyme in amino acid metabolism, may act by correcting some deficiency within the hypothalamus. Pyridoxine is involved particularly in the metabolism of dopamine and serotonin, low levels of which lead to high levels of prolactin and aldosterone, possibly explaining the fluid retention experienced in PMS. It may also account for some of the psychological symptoms attributable to alterations in neurotransmitter levels.

Vitamin B6 is taken daily, and this can be on a continuous basis or during the second half of the menstrual cycle. Placebo-controlled randomized trials do not demonstrate any meaningful benefit of B6 in PMS. There are safety concerns with its use since doses > 200 mg/day are associated with peripheral neuropathy.

Probably effective

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)

PMS often presents with symptoms similar to those of anxiety and depression and this association has resulted in treatment with a variety of antidepressants. Reduced platelet uptake of serotonin and reduced levels in the blood of women with PMS during the luteal phase, have been used to imply a role for SSRIs in PMS treatment. Meta-analysis shows that SSRIs are effective, with around 60% of those with severe PMS reporting a reduction in physical and behavioural symptoms compared with around 30% of controls. This effectiveness is often apparent after only one or two cycles. Side-effects include insomnia, gastrointestinal disturbances, fatigue and loss of libido, but may be acceptable at the recommended low dose. Intermittent use in the luteal phase may be as effective as continuous daily dosing. A gradual rather than abrupt withdrawal of SSRIs is appropriate if the SSRI has been taken on a continuous basis, in order to avoid symptoms of withdrawal.

Ovarian suppression

Since the majority of PMS symptoms can be attributed to cyclical ovarian hormone production, the suppression of ovulation is a logical treatment option. The effectiveness of combined hormonal contraceptives (CHC) for the treatment of PMS is uncertain; some research suggests an improvement in symptoms, whereas other research suggests symptom exacerbation. Limited evidence supports the use of third-generation CHC containing drospirenone as the progestogen. It is logical to consider taking this CHC continuously. Depot medroxyprogesterone, a long-acting injectable progestogen, may also be helpful.

The synthetic androgen, danazol, suppresses ovulation and a relatively low dose of 200 mg twice daily is effective in improving the symptoms of mastalgia. Use of danazol is limited by its potential for irreversible virilization, and effective contraception should be used to avoid virilization of a female fetus.

Transdermal oestrogen (100 μg/day), by way of patches designed for hormone replacement therapy (HRT), is associated with an improvement in PMS symptoms. If the woman has not had a hysterectomy, a progestogen is required to avoid endometrial stimulation, hyperplasia and possible malignant transformation. The lowest dose of progestogen is appropriate; the levonorgestrel intrauterine system is particularly suitable, since the serum level of progestogen is very low, thus minimizing the risk of progestogenic side-effects (which may mimic/exacerbate PMS).

Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues are a highly effective way of suppressing ovarian function, and are therefore a highly effective treatment for severe refractory PMS. As oestrogen is suppressed to postmenopausal levels, however, the PMS symptoms may be replaced by menopausal ones, including hot flushes. These in turn can be minimized with the use of continuous combined ‘add-back’ HRT. A therapeutic trial of GnRH analogues with add-back HRT is often beneficial in clarifying the diagnosis and establishing that the woman can tolerate an HRT preparation should oophorectomy become appropriate (see below). GnRH analogues without add-back HRT are only licensed for 6 months of use because of the risks of osteoporosis and other side-effects associated with a premature menopause. Use beyond 6 months must include add-back HRT and regular measurement of bone density. Although generally accepted as a treatment option, GnRH analogues are not specifically licensed for use in PMS.

Bilateral oophorectomy

This is an effective treatment for PMS. It is, however, a surgical procedure and therefore not without significant short-term surgical risks. The procedure can usually be undertaken laparoscopically. There are also the longer-term risks of premature menopause if HRT is not taken postoperatively. This surgical option is therefore only suitable for those very likely to benefit from it, as suggested by a definite response to a GnRH analogue, and only in those who have completed their family. It is also reasonable not to opt for this procedure, if the natural menopause is likely to be occurring in the near future.

Individual management strategy

Given the large number of treatments advocated, it can be difficult to find a practical way through them. As PMS is usually a chronic condition, it is important to consider the side-effect profile of treatments that may be used over many years. Once the diagnosis is established by prospective symptom diary-keeping, it seems sensible to try those treatments with fewest significant side-effects, initially diet, regular aerobic exercise and techniques aimed at stress reduction. A significant proportion of women will benefit from these three tried together, and drug therapy can then be considered for those who do not improve sufficiently.

Appropriate first-line drug therapy includes low-dose SSRI or a third-generation CHC. The next stage is oestrogen patches or ovarian suppression with a GnRH analogue. Successful symptom improvement, however, leaves a dilemma, as continuous treatment is not appropriate. Long-term suppression with medroxyprogesterone acetate 3-monthly i.m. may be appropriate. Bilateral oophorectomy should be reserved for the severest cases, with a preoperative trial of GnRH analogue beforehand.