37

Prematurity

Aetiology and predisposing factors

Identifying women at increased risk of pre-term birth

Prevention of the onset of pre-term labour

Diagnosis and management of pre-term labour

Introduction

Prematurity is defined as delivery between 24 and 37 weeks’ gestation and occurs in 6–10% of births. There is often no apparent predisposing cause for pre-term labour (idiopathic) but it is recognized to be more common with multiple pregnancy, antepartum haemorrhage, fetal growth restriction, cervical incompetence, amnionitis, congenital uterine anomaly, polyhydramnios and systemic maternal infection. Almost one-third of pre-term births in the UK are iatrogenic following deliberate medical intervention when the risk of continuing the pregnancy for either the mother or the fetus outweighs the risks of prematurity.

To be born prematurely is a potentially serious hazard. Fetal morbidity and mortality rates are inversely proportional to the maturity of organ systems, especially the lungs, brain and gastrointestinal tract. Prematurity especially before 33 weeks’ gestation is the leading cause of perinatal morbidity and mortality. It is exceptional to survive if delivered before 24 weeks’ gestation, especially without significant disability. In the most recent UK perinatal mortality report from the Centre for Maternal and Child Enquiries (CMACE 2011), 67% of neonatal deaths in 2009 occurred under 37 weeks’ gestation. Of those infants who survive, 10% will suffer some form of long-term disability requiring additional needs, and a greater number may suffer from lesser developmental or behavioural problems; these proportions are higher with earlier gestational age.

Research into mechanisms involved in pre-term delivery and its prevention has been relatively unsuccessful to date; as a result, prematurity is currently one of the most challenging problems facing both obstetricians and paediatricians.

Definitions

Pre-term – a gestation of less than 37 completed weeks

Very pre-term – a gestation of less than 32 completed weeks

Pre-term labour – regular uterine contractions accompanied by effacement and dilatation of the cervix after 20 weeks and before 37 completed weeks

Pre-term pre-labour rupture of the membranes (PPROM) – rupture of the fetal membranes before 37 completed weeks and before the onset of labour

Low birth weight (LBW) – birth weight of less than 2501 g. It is important to note that low-birth-weight infants may be pre-term or growth restricted or both (p. 35)

Very low birth weight (VLBW) – birth weight of less than 1501 g

Extremely low birth weight (ELBW) – birth weight of less than 1000 g

Perinatal mortality rates – see Chapter 48.

Aetiology and predisposing factors

The incidence of pre-term birth is 6–10% (Table 37.1) and approximately 1.5% will deliver before 32 weeks. Although only 0.5% deliver before 28 weeks, this latter group accounts for two-thirds of the neonatal deaths.

Table 37.1

Aetiology of pre-term delivery

| Spontaneous labour, cause unknown | 35% |

| Elective delivery (iatrogenic), e.g. maternal hypertension, fetal growth problems, antepartum haemorrhage | 25% |

| Pre-term premature ruptured membranes | 25% |

| Multiple pregnancy | 15% |

The aetiological factors that trigger spontaneous pre-term labour are largely unknown, but may be mediated through cytokines and prostaglandins. In some instances, it is related to increased uterine size or to other hormonal factors. Infection has been implicated in pre-term delivery and it may be that bacterial toxins initiate an inflammatory process in the chorioamniotic membranes, which in turn release prostaglandins. Bacteria may damage membranes by direct protease action, or by stimulating production of immune mediators like 5-hydroxytryptamine, which stimulate smooth muscle cells. None of these postulated mechanisms satisfactorily explains every case of pre-term labour and the aetiology is therefore considered to be multifactorial.

Identifying women at increased risk of pre-term birth

A number of techniques or strategies have been proposed to identify pregnancies at increased risk of pre-term birth. They include clinical risk scoring, bacteriological assessment of the vagina, cervical assessment and the measurement of fetal fibronectin (Ffn).

The ‘risk scoring’ is based on the recognized risk factors available from the maternal obstetric, gynaecological and medical histories together with smoking status, body weight and socioeconomic status. The strongest of these is a history of previous pre-term birth but this is clearly not applicable to first-time mothers. Other recognized associations are presented in Box 37.1. Unfortunately, the performance of these scoring systems has been poor, with sensitivities quoted as less than 40%, but the system at least serves to highlight the potentially avoidable factors such as urinary tract infections, vaginal infections, smoking, drugs and chaotic lifestyle.

Screening for and treating vaginal infection has been considered as a mechanism to identify and treat those at high risk of pre-term labour. Conflicting results have been demonstrated. Bacterial vaginosis, which is present in 10–20% of pregnant women, is associated with a doubling of the risk of pre-term delivery if identified in the third trimester, but a five-fold increased risk if identified in the first or early second trimester. Unfortunately, clinical trials have not demonstrated that treating bacterial vaginosis reduces the risk of pre-term labour. It is reasonable to treat bacterial vaginosis identified in early pregnancy, in those considered to have other risk factors for pre-term labour.

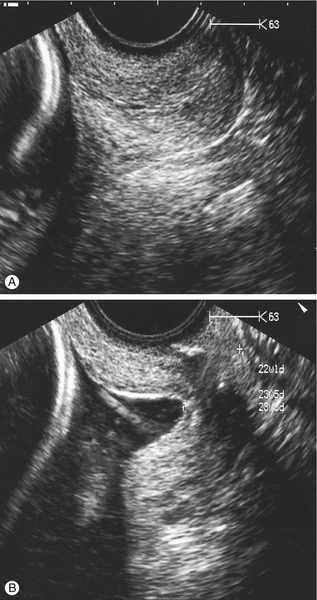

More recently, interest has focused on transvaginal ultrasound in measurement of the cervix. A normal cervical length is between 34 and 40 mm and there should be no funnelling at the internal os (Fig. 37.1). A cervical length < 15 mm at 23 weeks occurs in < 2% of pregnancies but accounts for 90% of those who will deliver before 28 weeks. The risk of spontaneous pre-term labour at less than 34 weeks’ gestation with a cervical length < 15 mm is 34%, rising to 78% if cervical length is < 5 mm.

Fig. 37.1Cervical length as measured by transvaginal scan.

(A) Normal. (B) There is shortening of the cervix and funnelling at the internal os. Note the transvaginal cervical suture in situ.

Fetal fibronectin (Ffn) is an adhesion molecule involved in maintaining the integrity of the choriodecidual extracellular matrix. It is usually not detectable on a high vaginal swab of cervicovaginal secretions after 20 weeks until term or membrane rupture, but if it is found to be present, it implies disruption of the extracellular matrix or an inflammatory process. The presence of Ffn at 23 weeks predicts 60% of spontaneous pre-term births at < 28 weeks in unselected pregnancies but the positive predictive ability is low, making it unsuitable for risk categorization in asymptomatic pregnancies. On the other hand, a negative Ffn result may provide reassurance about a lower probability of pre-term labour, and may guide decisions about the timing of corticosteroid administration or in-utero transfer.

Prevention of the onset of pre-term labour

Antibiotics

Evidence suggests that screening for and treating asymptomatic bacteriuria can reduce the risk of pre-term labour. Evidence with regards to screening for and treating vaginal organisms is more controversial. As noted above, although meta-analyses have suggested that organisms such as those causing bacterial vaginosis can be treated effectively with antibiotics, evidence does not demonstrate an effect on reducing pre-term delivery rates. Some studies have suggested that, in low-risk women, if such organisms are detected early in pregnancy, e.g. first trimester, then benefit can be gained by treating with clindamycin either vaginally or orally. It has been proposed that the demonstrated lack of effect of antibiotics in treating and preventing pre-term labour is because of introduction of treatment after intrauterine bacterial colonization and the subsequent inflammatory cascade have already become established.

Progesterone

Progesterone supplementation may reduce the risk of pre-term birth. Potential mechanisms are reduced gap-junction formation, oxytocin antagonism (leading to relaxation of smooth muscle), maintenance of cervical integrity and antiinflammatory effects. Progesterone is administered intramuscularly, vaginally or rectally, and is usually commenced around 20 weeks. Selecting the group of women who will benefit from progesterone supplementation is the subject of active research but women with a singleton pregnancy, and previous pre-term birth and/or a short cervix appear to benefit.

Cervical cerclage

There is some evidence that elective cervical cerclage (Shirodkar suture, McDonald suture, see History box) performed in early second trimester is of benefit in those with a history of pre-term labour or mid-trimester pregnancy loss. A non-absorbable high-strength suture (Mersilene or similar) is inserted vaginally around the cervix under anaesthesia. It is removed electively between 36 and 37 weeks’ gestation or as an emergency if labour establishes beforehand (see Fig. 37.1). Transabdominal cervico-isthmic cerclage is a specialist procedure principally reserved those with for poor pregnancy outcome despite previous transvaginal cervical cerclage. This can be performed pre-conception by laparotomy or laparoscopy. Subsequent delivery is by elective caesarean and the suture is usually left in place for the benefit of any future pregnancies.

‘Rescue’ cerclage refers to the emergency use of a suture in early pre-term labour before or at the limit of viability where cervical incompetence is suspected. Careful selection criteria are employed since cerclage in the presence of clinical or subclinical infection can result in significant maternal morbidity with little advantage to the fetus.

Prophylactic tocolytics and bed rest are not effective interventions in the prevention of pre-term labour and delivery.

Diagnosis and management of pre-term labour

The definition of pre-term labour is similar to the diagnosis of labour at term: regular painful contractions associated with progressive cervical dilatation. Diagnosis may be difficult in the early stages because in most cases, regular painful contractions may not progress to established labour. Labour may also be insidious, or heralded by a ‘show’, bleeding or abruption. Objective assessment may be helpful: a negative Ffn test means that only around 1% of women will deliver within a week, permitting a high threshold for any interventions. Similarly, a cervical length of > 20 mm means that the contractions are likely to represent ‘false’ rather than ‘true’ pre-term labour.

Maternal well-being is assessed by seeking evidence of infection or haemorrhage. The white cell count may be raised in infection, as may the C-reactive protein. Vaginal swabs and urine should be sent for culture.

The fetus can be assessed with cardiotocography, and then ideally with ultrasound to evaluate liquor volume, presentation, placental site and any evidence of fetal abnormality. If pre-term delivery is likely, the paediatrician should be alerted and arrangements made for in-utero transfer if local facilities for resuscitation are insufficient.

Inhibition of pre-term labour

In view of the high morbidity and mortality associated with prematurity, an attempt may be made to stop pre-term labour, particularly at gestations less than 33 weeks. The use of drugs to suppress uterine activity (‘tocolysis’) may allow sufficient delay for a course of steroids to be administered, or an in-utero transfer to take place, but whether this delay translates into an improvement for the baby in the long term, remains unproven. As no tocolytic drug has been shown to reduce perinatal mortality or neonatal morbidity, it is also reasonable to use no tocolysis. Contraindications are listed in Box 37.2.

The most commonly used tocolytics are discussed below. If the decision is made to use a tocolytic drug, nifedipine and atosiban appear to have comparable effectiveness in delaying delivery, with fewer maternal adverse effects and less risk of rare serious adverse events than alternatives such as indometacin. Nifedipine is also considerably less expensive. There is little information about the long-term growth and development of the fetus exposed to any of these.

Nifedipine

This calcium-channel blocker inhibits inward calcium flow across cell membranes. The side-effects of dizziness, hypotension, flushing and headache are all related to peripheral dilatation, but serious adverse effects are rare. There seem to be no obvious adverse fetal effects provided there is no precipitous fall in maternal blood pressure resulting in uterine underperfusion.

Cyclo-oxygenase inhibitors

Most experience in this group of drugs is with indometacin. It inhibits cyclo-oxygenase, the enzyme which converts fatty acids into prostaglandin endoperoxidases, and it thereby reduces prostaglandin production. Indometacin may lead to maternal gastrointestinal irritation, headaches and dizziness but, in contrast to the beta-sympathomimetics, the main risks are to the fetus. The patency of the ductus arteriosus is prostaglandin-dependent and ductal constriction has been demonstrated in human fetuses from as early as 27 weeks’ gestation in response to these drugs. Significant adverse neonatal effects have not been convincingly demonstrated, however, but caution is nonetheless advised.

Oxytocin antagonist

Atosiban is a synthetic competitive inhibitor of oxytocin which binds to and blocks myometrial oxytocin receptors and leads to an inhibition of intracellular calcium release. It has been shown to be as effective as ritodrine (a beta-sympathomimetic no longer manufactured), but has minimal maternal or fetal side-effects.

Beta-sympathomimetics

Salbutamol and terbutaline, which are chemically related to adrenaline (epinephrine) and noradrenaline (norepinephrine), cause stimulation of beta2-adrenergic receptors on myometrial cell membranes. This leads to a reduction in intracellular calcium concentrations and inhibition of the actin–myosin interaction necessary for smooth muscle contraction. Beta-sympathomimetics stimulate the sympathetic nervous system and side-effects are common, including maternal (and fetal) tachycardia, visual disturbances, skin flushing, nausea, vomiting, hypokalaemia and hyperglycaemia. Pulmonary oedema and arrhythmias may occur, and maternal deaths have been reported. However, with safer alternatives available, the main current use for beta-sympathomimetics is for short-term uterine relaxation during external cephalic version.

Pre-term pre-labour rupture of the membranes (PPROM)

This occurs in 2–3% of all pregnancies but in 20–50% of all spontaneous pre-term deliveries and is more likely with polyhydramnios, twins, and vaginal infection. If the mother does not establish in labour, the problem is one of balancing the increased risk of developing ascending chorioamnionitis leading to maternal and fetal morbidity, against the risks of prematurity and induction of labour.

The neonatal outcome is more guarded the earlier the membrane rupture occurs, on account of secondary pulmonary hypoplasia and severe skeletal deformities resulting from the absence of amniotic fluid (see Box 37.3). The amniotic fluid normally allows fetal movement and it circulates into the fetal lungs. Pulmonary hypoplasia occurs in 50% of cases with spontaneous membrane rupture before 20 weeks and in 3% after 24 weeks; reliable antenatal prediction of pulmonary hypoplasia remains elusive.

Chorioamnionitis is potentially extremely serious for both mother and baby, as both may develop rapid and overwhelming fatal sepsis. Infection supervenes after the membranes have ruptured in between 0.5% and 25% of cases, depending on criteria employed for diagnosis, and is more likely if vaginal examinations have been performed. Vaginal examinations are therefore contraindicated unless there is strong evidence of labour. It may be considered appropriate to carry out a sterile speculum examination to initially confirm the diagnosis, exclude cord prolapse and take a high vaginal swab (HVS). However an HVS is not a predictor of subsequent infection, the procedure may actually introduce infection, and in any case the membrane rupture may be a secondary process resulting from an already establishing infection.

The diagnosis of chorioamnionitis is suggested by maternal pyrexia, maternal and fetal tachycardia, abdominal pain, uterine tenderness, draining offensive liquor and raised blood inflammatory markers. It is also more likely if there has been a proven vaginal or urinary infection. It is therefore important to check the maternal temperature and inflammatory markers, and urine for infection. It should be noted that the white cell count rises after maternal steroid administration (see below), and C-reactive protein measurements are therefore preferred as a better predictor of infection.

Management of PPROM

Most mothers will establish in labour, with around 75% of those at 28 weeks’ gestation delivering within 7 days. There is again no evidence that tocolysis is beneficial in this group. For those who do not establish in labour, regular fetal monitoring is essential. It is considered acceptable practice to manage these women on an outpatient basis following an initial inpatient stay and the woman is advised to take her own temperature at home four times a day. Delivery around 34–35 weeks strikes the appropriate balance between maturity and risk of chorioamnionitis but it is important to individualize management. As there is such a high risk of per-term delivery, corticosteroids should be given if PPROM occurs at less than 36 weeks (see above). Prophylactic oral erythromycin (250 mg QID) for 10 days following membrane rupture has been shown to be associated with improved neonatal outcome when compared to placebo and is routinely recommended.

Delivery and optimizing neonatal outcome

Prematurity leads to neonatal morbidity and mortality through a number of mechanisms, despite advances in neonatal medicine, and interventions to reduce harm to the immature fetus ex-utero have been developed.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids should be administered to the mother if delivery before term is considered likely; among their many effects they cross the placenta and increase the amount of pulmonary surfactant produced by type II fetal pneumocytes. Betamethasone or dexamethasone 24 mg i.m. is given in divided doses over 24 h reducing the incidence of respiratory distress syndrome (hyaline membrane disease) by 44%. In addition, the incidence of intraventricular cerebral haemorrhage and neonatal death is reduced by 46% and 31%, respectively. There are also reductions in necrotizing enterocolitis and neonatal intensive care admission, and no adverse neurological or cognitive effects following steroid treatment have been demonstrated. There is no identifiable increase in the incidence of maternal or fetal infection, but steroids are contraindicated if there is active maternal sepsis. It is advisable to limit steroid administration to one ‘course’ during the pregnancy as there are some concerns regarding the effect repeated doses may have on the developing fetus, and there is no demonstrable benefit to the fetus with additional courses. Steroids can be used in women with insulin-dependent diabetes if required, but as they may precipitate ketoacidosis, tight control of blood glucose with a sliding-scale is recommended.

As described above, tocolysis can be used to delay delivery temporarily, and allow time for completion of a full steroid course, or an in-utero transfer if a higher level of neonatal care is anticipated than is available locally. Centres with advanced facilities for neonatal resuscitation can justifiably avoid tocolysis, and any inherent associated risks.

Prevention of infection

Ten days of oral erythromycin following PPROM has been shown to be of benefit to the fetus and is strongly recommended. Antibiotics for specific culture-proven infections are also known to prevent the development of systemic maternal infection and reduced pre-term delivery, and are also recommended. In pre-term labour, intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (penicillin or clindamycin) is recommended to reduce infection of the neonate with Group B Streptococcus (Streptococcus agalactiae) only in women known to be colonized.

Should a woman with PPROM develop clinical signs of chorioamnionitis, broad spectrum antibiotics should be administered and expediting delivery considered in both the maternal and fetal interest: the mother to remove the source of infection, and the baby to minimize the risk of sepsis and subsequent cerebral palsy.

Magnesium sulphate

Magnesium sulphate, as used in severe pre-eclampsia and eclampsia, has been noted to reduce the relative risk of cerebral palsy, especially at earlier gestations. A 30-week cut-off is often used to focus treatment on babies most likely to benefit, although smaller positive effects are seen up to 37 weeks.

Intrapartum monitoring

If labour continues or tocolysis is unsuccessful, then close monitoring is important as a pre-term fetus is more susceptible to intrapartum hypoxia and acidosis than is a fetus at term. Women in pre-term labour should be cared for on the labour ward with close monitoring of the fetus, usually in the form of a continuous CTG if the fetus is over 26 weeks gestation. Complications such as abnormal lie, cord prolapse, abruption and intrauterine infection are more common. Good communication with the paediatric team is needed to allow attendance and preparation for delivery.

Mode of delivery

The mode of delivery needs to be considered. While caesarean section may be indicated for an apparently compromised fetus, there is no evidence to support liberal use of caesarean section; indeed, pre-term delivery by caesarean section may lead to significant fetal trauma. The vaginal route is preferred for those with cephalic presentation and there is no evidence to support the routine advocacy of epidurals, forceps or episiotomy.

In the event that an assisted vaginal delivery is required, forceps are preferred over vacuum devices under 34 weeks to avoid the increased risk of cephalohaematoma, subgaleal haematoma and intraventricular haemorrhage. Delayed cord clamping should be undertaken if the condition of the baby permits to improve circulating volume and hence organ perfusion. Very pre-term babies are particularly susceptible to hypothermia and it is often helpful to place these babies quickly into a plastic bag to minimize this (Fig. 37.2).

There is uncertainty about the most appropriate route of delivery in those with breech presentation. In current clinical practice, most pre-term breeches before 26 weeks are delivered vaginally and many of those above this gestation are delivered by caesarean section.