CHAPTER 398 Pregnancy and the Vascular Lesion

A cerebrovascular lesion in the setting of pregnancy presents a unique neurosurgical dilemma in which the health of two patients—mother and child—are at stake. Cerebrovascular disorders during pregnancy and the puerperium are infrequent but can be devastating to the mother and fetus. The precise incidence of cerebrovascular disease during pregnancy is uncertain; estimates range from 0.3 to 9 per 100,000 deliveries.1–3 Of maternal deaths, however, 12% to 80% are due to cerebrovascular disease.4–6 Cerebrovascular disease during pregnancy results in higher maternal and fetal mortality and morbidity rates than in nonpregnant women of the same age.5,7,8

Stroke

Stroke is defined by the World Health Organization as a “neurological deficit of cerebrovascular cause that persists beyond 24 hours or is interrupted by death within 24 hours.” Estimates of the incidence of cerebral infarction in pregnant women vary widely and range from 0.004% to 0.2% of all deliveries.4 The risk for stroke in a pregnant patient is 13 times higher than in an age-matched nonpregnant patient and can be attributed to a variety of causes. The most common causes of stroke in pregnancy are arterial occlusion, venous thrombosis, and preeclampsia/eclampsia.9,10 Hypertension is a major underlying factor for the development of these conditions and subsequent stroke.10

Arterial embolism or thrombosis accounts for 60% to 80% of cases of ischemic stroke during pregnancy.11 Stroke secondary to arterial occlusion tends to occur during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy and during the first week after delivery.11 This gestational pattern corresponds to appearance of the hypercoagulable state in the latter stages of pregnancy and the puerperium.

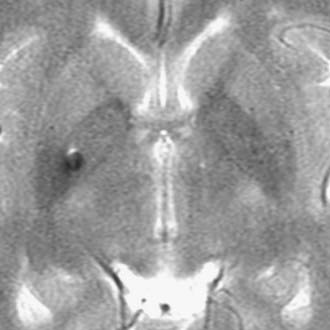

All patients suspected of having an ischemic stroke should undergo a thorough radiologic and laboratory investigation. Computed tomography (CT) is a good initial study to exclude hemorrhagic stroke and can identify some cases of ischemic stroke, depending on the region of the brain affected and the length of time since arterial occlusion. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has greater sensitivity and resolution than CT. Angiography can be useful, particularly when intra-arterial thrombolytic treatment is anticipated. Helpful initial laboratory investigations include a complete blood count, electrolytes, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, coagulation studies, and urinalysis. When a cardiac source is suspected, a chest radiograph, electrocardiogram, and echocardiogram should be obtained. Transesophageal echocardiography is superior to transthoracic echocardiography and is safe for pregnant patients.12 Carotid duplex ultrasound and magnetic resonance angiography are noninvasive techniques for investigating extracranial carotid disease.

Intracranial venous thrombosis occurs at an estimated incidence of 1 in 2500 to 1 in 10,000 deliveries13 and accounts for 20% to 40% of cases of ischemic stroke during pregnancy.11 It is more common in pregnant women than in nonpregnant women.14 This disorder tends to develop in multiparous women 3 days to 4 weeks after childbirth, with most cases occurring in the second or third postpartum week.11,13,15–18 Intracranial venous thrombosis during pregnancy is less common, with just a quarter of cases occurring during actual pregnancy as opposed to after pregnancy.13,14,19–21 Most cases are idiopathic,21 although many systemic conditions can predispose to intracranial venous thrombosis. Venous sinus thrombosis is thought to arise as a result of the hypercoagulable state of pregnancy, in addition to alterations in cerebral vessel walls.22,23

More than 70% of cases involve occlusion of multiple venous sinuses or cerebral veins.24 Cortical veins are involved more commonly than deep cerebral and cerebellar veins.21 Headache is the most common initial symptom.25 Other common clinical findings are nausea and vomiting, seizures, focal neurological deficits, fever, and altered mental status.21

The diagnosis of intracranial venous thrombosis is based on clinical findings and radiologic studies. Imaging modalities such as CT, MRI, and angiography are useful. Investigation of possible predisposing factors with tests such as coagulation studies is important. When the diagnosis is confirmed, management begins with adequate hydration and treatment of elevated intracranial pressure, hydrocephalus, and seizures.21 Treatment options for intracranial venous thrombosis include high doses of heparin (1000 IU/hr to start; activated partial thromboplastin time >1.5 to 2 times control) and endovascular fibrinolysis followed by heparinization and surgical thrombectomy.21 Einhaupl and colleagues found that patients receiving intravenous heparin for intracranial venous thrombosis had significantly better neurological outcomes and mortality rates than did patients receiving placebo treatment.26 Underlying predisposing disorders, such as sinusitis, must also be treated.21

Mortality rates of 33% for intracranial venous thrombosis have been reported15; however, neurological outcomes in survivors are usually good.21 Srinivasan found that 59% of patients recovered without significant neurological disability.15

Another entity that has been described as a cause of stroke is postpartum cerebral angiopathy (PCA).27 PCA is a disorder of blood vessels in recently pregnant patients that can be subdivided into three categories. Primary PCA occurs without a known etiology. Secondary PCA results from medications, particularly ergot derivatives. Tertiary PCA occurs in the setting of eclampsia. Angiography in patients with PCA reveals irregular narrowing of affected blood vessels.

Generally, the risk for stroke in a pregnant patient is at its peak during delivery.28 Specifically, the risk is greatest 2 days before delivery and 1 day after; there has also been found to be an increased occurrence of stroke 6 weeks after delivery.29 Other studies have identified racial differences in pregnancy-related stroke, with an increased incidence in patients of Asian descent.30

Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

Epidemiology

Generally speaking, intracranial hemorrhage can be either intracerebral (ICH) or subarachnoid (SAH). SAH accounts for approximately half the cases of intracranial hemorrhage in pregnant patients.16 The majority of SAH is from aneurysms, although a small proportion can be secondary to AVMs (discussed later).31 Other reported causes of SAH during pregnancy include mycotic aneurysms,32 postpartum angiopathy,33 and unidentifiable causes.34

The incidence of spontaneous SAH during pregnancy ranges from 0.01% to 0.05% of all pregnancies.6,8,35 This equates to 1 per 10,000, which is five times higher than in nonpregnant patients.9 Dias and Sekhar found the mean age for pregnant patients with aneurysmal hemorrhage to be 29.4 years and the mean gestational age to be 30.5 weeks.8 SAH accounts for approximately 5% of maternal mortality, a figure that has stayed consistent over time, and it is at least the third most common nonobstetric cause of maternal death.36–39 In some regions, SAH is the leading cause of nonobstetric maternal death.40 The overall mortality rate is 35%, which is comparable to that in the nonpregnant population.8

Certain periods of pregnancy confer an increased risk for aneurysmal rupture. The second and third trimesters of pregnancy are associated with an elevated risk for rupture because of the increase in cardiac output that takes place after the first trimester.41,42 This risk peaks at 30 to 34 weeks’ gestation.8 Aneurysmal rupture is also more common during the actual time of labor and delivery, presumably because of the hypertensive nature of childbirth.37

The menstrual and reproductive characteristics of the patient likewise play a role in the risk for aneurysmal rupture. SAH has been found to affect primiparous women more than multiparous women,42 but also the other way around.43 Okamoto and coworkers found that nulligravidity conferred a fourfold increased risk for aneurysmal SAH.44 In that same study, patients with earlier menarche (defined as onset before the age of 13 years) had a threefold increased risk. In a Taiwanese cohort, older age at first pregnancy and earlier pregnancies were risk factors.45 Contrarily, another study found that older age at first pregnancy was protective.46

Further research is needed to understand the endocrinology underlying aneurysms and pregnancy inasmuch as clinical studies have been inconclusive. Some studies have found increased parity to confer a long-term protective effect on the risk for SAH,47 whereas other data have shown an increased risk for hemorrhage with increasing parity.48 In addition, the use of hormone replacement therapy has been found to be protective against SAH.46

Management

The risk for recurrent bleeding during the remainder of pregnancy in patients with an untreated aneurysm is 33% to 50%,49,50 with a maternal mortality rate of 50% to 68%.49,51,52 In an analysis of 118 pregnant patients with aneurysmal SAH, Dias and Sekhar found that surgical treatment of a ruptured aneurysm was associated with significantly lower maternal and fetal mortality rates than was conservative treatment.8 Thus, management of aneurysmal SAH in pregnant patients should be the same as in patients who are not pregnant23,42,53,54 (i.e., the ruptured aneurysm should be treated). Unruptured aneurysms should be treated if they are symptomatic or enlarging.54 Afterward, the pregnancy can be allowed to progress to term. Such an approach of treatment of the aneurysm followed by delivery of the child has been found to result in good outcomes for both patients.55 In more complicated cases, however, it has been argued that treatment of the aneurysm should follow delivery of the child via cesarean section.56

The optimum mode of delivering a child in a patient with a treated or untreated aneurysm is debatable. Mosiewicz and associates assert that vaginal delivery is preferred by most clinicians, with just three indications for cesarean section: (1) if the clinical state of the mother is severe, (2) if the aneurysm is diagnosed at the time of labor, and (3) if the interval between labor and treatment of the aneurysm is less than 8 days.42 In contrast, Zukiel and colleagues argue that every pregnant patient with SAH should deliver via cesarean section.31 Such discrepancies in the approach to management suggest that each case is unique and should be individualized.

Endovascular techniques for treating aneurysms have been used and reported increasingly in pregnant patients, with good outcomes in both the mother and fetus.57–59

Outcomes

In most series, maternal mortality rates from SAH range from 30% to 50%,7,8 but rates as high as 83% have been reported.60 Dias and Sekhar found the overall maternal mortality rate from aneurysmal SAH to be 35%,8 similar to that in the nonpregnant population. The fetal mortality rate was 17%. The maternal mortality rate after SAH varies directly with clinical (Hunt and Hess) grade, with a peak reached at Hunt and Hess grade V.8 The maternal mortality rate in patients undergoing antepartum surgery for ruptured aneurysms (11%) was significantly lower than that for patients not undergoing surgery (63%).8 The fetal mortality rate was significantly better after surgery (5%) than without surgery (27%).8

Arteriovenous Malformations

The literature on AVMs in the setting of pregnancy is less extensive than that for aneurysmal SAH. AVMs account for 21% to 48% of hemorrhages during pregnancy and the puerperium.6,8,61,62 Whether pregnancy confers an increased risk for AVM rupture is controversial.23 Some authors have found an increased risk for rupture and attributed such findings to the augmented cardiac output associated with pregnancy38,63; however, others do not find such an increased risk.64 In untreated, ruptured AVMs, Sadasivan and colleagues found the incidence of rebleeding to be 27%.65

Management

Management of AVMs during pregnancy follows the principle of intervening only if needed. Sadasivan and associates propose the practice of operating on the AVM only in emergency situations; in stable patients, delivery of the child should come first.65 Given the hypertensive nature of natural childbirth, most authors advocate obstetric management via cesarean section.63,66

Other Vascular Lesions

Metastatic Choriocarcinoma

Metastatic choriocarcinoma is a rare cause of ICH and oncotic intracranial aneurysms. Choriocarcinoma is a form of gestational trophoblastic neoplasia and is the most malignant tumor associated with pregnancy67; it occurs in about 1 in 20,000 pregnancies.68 The mechanism of metastasis is hematogenous and is based on the ability of normal chorionic tissue to penetrate the uterine wall in search of blood vessels to nourish the fetus. In the cerebral vasculature, trophoblasts infiltrate the vessels just as they would in the uterus. Damaged vessels may thrombose, form an embolus, or weaken the vessel wall and form an aneurysm or varicosity.67,69 Metastatic choriocarcinoma in the brain has a high rate of spontaneous hemorrhage, second only to metastatic melanoma67; at autopsy, most metastatic brain lesions are found to be hemorrhagic.70 Intracranial hemorrhage is the mode of manifestation in two thirds of cerebral metastases.71

Intracranial hemorrhage secondary to metastatic choriocarcinoma may be intracerebral, subdural, or subarachnoid72; however, it is uncommon for a patient to harbor multiple intracranial vascular disorders.72,73 ICH can be located at any site in the brain where metastases have occurred. Oncotic aneurysms usually develop at distal sites in the distribution of the middle cerebral artery.73,74 The aneurysms can be single or multiple, large or small, and smooth or irregular.75 Typically, the aneurysms are fusiform.76 Intracranial hemorrhage is treated by craniotomy and clot evacuation. Oncotic aneurysms should be clipped or excised67,72,75 because they have a tendency to rehemorrhage77 or to cause thrombosis of the distal artery.78 A combination of radiation therapy and multiagent chemotherapy is recommended for patients with choriocarcinoma brain metastases; these patients have an overall survival rate of 18%.79

Postpartum Cerebral Vasospasm

Cerebral vasospasm is a rare complication of pregnancy and usually occurs during the postpartum period and for 3 weeks after delivery. The cause is not understood, but evidence indicates that postpartum vasospasm is a variant of eclampsia.80 Clinical findings include severe headache, fluctuating neurological deficits, and stroke.81 Hyperdynamic therapy combined with nimodipine may be an effective treatment of this disorder.80

Carotid-Cavernous Fistula

The spontaneous formation of a carotid-cavernous fistula is rarely associated with pregnancy and the puerperium.82–84 Hemodynamic changes, combined with alterations in blood vessel walls concomitant with pregnancy, may predispose to this lesion. The most common initial symptom is unilateral frontal headache, often accompanied by ipsilateral conjunctival injection and visual symptoms.85 This lesion tends to occur during the second half of pregnancy or the puerperium.85 The fistulas resolve spontaneously in 60% of cases,82 although successful treatment by embolization of the carotid artery has been reported.83

Pituitary Apoplexy

Severe shock around the time of delivery can lead to pituitary infarction and postpartum hypopituitarism (Sheehan’s syndrome). Stimulation of prolactin-secreting cells in the adenohypophysis during pregnancy causes enlargement of the pituitary, thereby putting it at risk for ischemia should severe hypotension occur. Infarction occurs in the region of the hypophyseal artery and rarely involves the neurohypophysis.85 Treatment consists of hormone replacement therapy.

Intracerebral Hemorrhage

Although some ICH is secondary to AVMs, others are spontaneous in nature. Non–AVM-related ICH accounts for 5% of maternal mortality36 and half of the cases of intracranial hemorrhage.16 Roughly a third of cases are associated with eclampsia.9,30

Moyamoya Disease

There have been a couple of cases of moyamoya disease manifested during pregnancy.41,86 Miyakawa and coauthors recommend elective cesarean section in such cases given that intracranial hemorrhage is associated with bearing down and active labor provokes hyperventilation-induced cerebral ischemia and hypertension.86

Amias AG. Cerebral vascular disease in pregnancy. I. Haemorrhage. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonw. 1970;77:100-120.

Barno A, Freeman DW. Maternal deaths due to spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1976;125:384-392.

Barrett JM, Van Hooydonk JE, Boehm FH. Pregnancy-related rupture of arterial aneurysms. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1982;37:557-566.

Dias MS, Sekhar LN. Intracranial hemorrhage from aneurysms and arteriovenous malformations during pregnancy and the puerperium. Neurosurgery. 1990;27:855-865.

Giannotta SL, Daniels J, Golde SH, et al. Ruptured intracranial aneurysms during pregnancy. A report of four cases. J Reprod Med. 1986;31:139-147.

Kizilkilic O, Albayram S, Adaletli I, et al. Endovascular treatment of ruptured intracranial aneurysms during pregnancy: report of three cases. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2003;268:325-328.

Maymon R, Fejgin M. Intracranial hemorrhage during pregnancy and puerperium. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1990;45:157-159.

Mhurchu CN, Anderson C, Jamrozik K, et al. Hormonal factors and risk of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: an international population-based, case-control study. Stroke. 2001;32:606-612.

Miller HJ, Hinkley CM. Berry aneurysms in pregnancy: a 10 year report. South Med J. 1970;63:279. passim

Minielly R, Yuzpe AA, Drake CG. Subarachnoid hemorrhage secondary to ruptured cerebral aneurysm in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1979;53:64-70.

Piotin M, de Souza Filho CB, Kothimbakam R, et al. Endovascular treatment of acutely ruptured intracranial aneurysms in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1261-1262.

Pool JL. Treatment of intracranial aneurysms during pregnancy. JAMA. 1965;192:209-214.

Riviello C, Ammannati F, Bordi L, et al. Pregnancy and subarachnoid hemorrhage: a case report. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2004;16:245-246.

Robinson JL, Hall CS, Sedzimir CB. Arteriovenous malformations, aneurysms, and pregnancy. J Neurosurg. 1974;41:63-70.

Robinson JL, Hall CJ, Sedzimir CB. Subarachnoid hemorrhage in pregnancy. J Neurosurg. 1972;36:27-33.

Roman H, Descargues G, Lopes M, et al. Subarachnoid hemorrhage due to cerebral aneurysmal rupture during pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2004;83:330-334.

Sadasivan B, Malik GM, Lee C, et al. Vascular malformations and pregnancy. Surg Neurol. 1990;33:305-313.

Selo-Ojeme DO, Marshman LA, Ikomi A, et al. Aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage in pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2004;116:131-143.

Stoodley MA, Macdonald RL, Weir BK. Pregnancy and intracranial aneurysms. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 1998;9:549-556.

Trivedi RA, Kirkpatrick PJ. Arteriovenous malformations of the cerebral circulation that rupture in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;23:484-489.

1 Sachs BP, Brown DA, Driscoll SG, et al. Maternal mortality in Massachusetts. Trends and prevention. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:667-672.

2 Sharshar T, Lamy C, Mas JL. Incidence and causes of strokes associated with pregnancy and puerperium. A study in public hospitals of Ile de France. Stroke in Pregnancy Study Group. Stroke. 1995;26:930-936.

3 Guyer B, Strobino DM, Ventura SJ, et al. Annual summary of vital statistics—1994. Pediatrics. 1995;96:1029-1039.

4 Wiebers DO, Whisnant JP. The incidence of stroke among pregnant women in Rochester, Minn, 1955 through 1979. JAMA. 1985;254:3055-3057.

5 Gibbs CE. Maternal death due to stroke. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1974;119:69-75.

6 Sawin P. Spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage in pregnancy and the puerperium. Neurosurgical Aspects of Pregnancy. 1996:85-99.

7 Barrett JM, Van Hooydonk JE, Boehm FH. Pregnancy-related rupture of arterial aneurysms. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1982;37:557-566.

8 Dias MS, Sekhar LN. Intracranial hemorrhage from aneurysms and arteriovenous malformations during pregnancy and the puerperium. Neurosurgery. 1990;27:855-865.

9 Fox MW, Harms RW, Davis DH. Selected neurologic complications of pregnancy. Mayo Clin Proc. 1990;65:1595-1618.

10 Vilela P, Duarte J, Goulao A. Cerebrovascular disease in pregnancy and puerperium. Acta Med Port. 2001;14:49-54.

11 Wiebers DO. Ischemic cerebrovascular complications of pregnancy. Arch Neurol. 1985;42:1106-1113.

12 Stoddard MF, Longaker RA, Vuocolo LM, et al. Transesophageal echocardiography in the pregnant patient. Am Heart J. 1992;124:785-787.

13 Bansal BC, Gupta RR, Prakash C. Stroke during pregnancy and puerperium in young females below the age of 40 years as a result of cerebral venous/venous sinus thrombosis. Jpn Heart J. 1980;21:171-183.

14 Jeng JS, Tang SC, Yip PK. Stroke in women of reproductive age: comparison between stroke related and unrelated to pregnancy. J Neurol Sci. 2004;221:25-29.

15 Srinivasan K. Cerebral venous and arterial thrombosis in pregnancy and puerperium. A study of 135 patients. Angiology. 1983;34:731-746.

16 Jaigobin C, Silver FL. Stroke and pregnancy. Stroke. 2000;31:2948-2951.

17 Estanol B, Rodriguez A, Conte G, et al. Intracranial venous thrombosis in young women. Stroke. 1979;10:680-684.

18 Imai WK, Everhart FRJr, Sanders JMJr. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis: report of a case and review of the literature. Pediatrics. 1982;70:965-970.

19 Fehr PE. Sagittal sinus thrombosis in early pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1982;59:7S-9S.

20 Lavin PJ, Bone I, Lamb JT, et al. Intracranial venous thrombosis in the first trimester of pregnancy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1978;41:726-729.

21 Hamilton M, Ziai W, Hull R. Venous thrombotic disorders in pregnancy. Neurosurgical Aspects of Pregnancy. 1996:101-134.

22 Biller J, Adams HPJr. Cerebrovascular disorders associated with pregnancy. Am Fam Physician. 1986;33:125-132.

23 Mas JL, Lamy C. Stroke in pregnancy and the puerperium. J Neurol. 1998;245:305-313.

24 Bousser MG, Chiras J, Bories J, et al. Cerebral venous thrombosis—a review of 38 cases. Stroke. 1985;16:199-213.

25 Galan HL, McDowell AB, Johnson PR, et al. Puerperal cerebral venous thrombosis associated with decreased free protein S: a case report. J Reprod Med. 1995;40:859-862.

26 Einhaupl KM, Villringer A, Meister W, et al. Heparin treatment in sinus venous thrombosis. Lancet. 1991;338:597-600.

27 Sengoku R, Iguchi Y, Yaguchi H, et al. A case of postpartum cerebral angiopathy with intracranial hemorrhage and subarachnoid hemorrhage immediately after delivery. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 2005;45:376-379.

28 Salonen Ros H, Lichtenstein P, Bellocco R, et al. Increased risks of circulatory diseases in late pregnancy and puerperium. Epidemiology. 2001;12:456-460.

29 Helms AK, Kittner SJ. Pregnancy and stroke. CNS Spectr. 2005;10:580-587.

30 Jeng JS, Tang SC, Yip PK. Incidence and etiologies of stroke during pregnancy and puerperium as evidenced in Taiwanese women. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2004;18:290-295.

31 Zukiel R, Jankowski R, Tokarz F. Spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage in pregnancy. Neurol Neurochir Pol. suppl 1. 1992:50-56.

32 Powell S, Rijhsinghani A. Ruptured bacterial intracranial aneurysm in pregnancy. A case report. J Reprod Med. 1997;42:455-458.

33 Moussouttas M, Abubakr A, Grewal RP, et al. Eclamptic subarachnoid haemorrhage without hypertension. J Clin Neurosci. 2006;13:474-476.

34 Tanguay JJ, Allegretti PJ. Postpartum intracranial hemorrhage disguised as preeclampsia. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26:247. e5-6

35 Maymon R, Fejgin M. Intracranial hemorrhage during pregnancy and puerperium. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1990;45:157-159.

36 Barnes JL, Abbott KH. Cerebral complications incurred during pregnancy and the puerperium. Calif Med. 1959;91:237-244.

37 Barno A, Freeman DW. Maternal deaths due to spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1976;125:384-392.

38 Newton CL, Bell SD. Arteriovenous malformation in the pregnant patient: a case study. J Neurosci Nurs. 1995;27:109-112.

39 Lin MJ. Causes of maternal death. A 10-year case analysis. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 1992;27:12-14. 57

40 Selo-Ojeme DO, Marshman LA, Ikomi A, et al. Aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage in pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2004;116:131-143.

41 Enomoto H, Goto H. Moyamoya disease presenting as intracerebral hemorrhage during pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 1987;20:33-35.

42 Mosiewicz A, Jakiel G, Janusz W, et al. Treatment of intracranial aneurysms during pregnancy. Ginekol Pol. 2001;72:86-92.

43 Robinson JL, Hall CS, Sedzimir CB. Arteriovenous malformations, aneurysms, and pregnancy. J Neurosurg. 1974;41:63-70.

44 Okamoto K, Horisawa R, Kawamura T, et al. Menstrual and reproductive factors for subarachnoid hemorrhage risk in women: a case-control study in Nagoya, Japan. Stroke. 2001;32:2841-2844.

45 Yang CY, Chang CC, Kuo HW, et al. Parity and risk of death from subarachnoid hemorrhage in women: evidence from a cohort in Taiwan. Neurology. 2006;67:514-515.

46 Mhurchu CN, Anderson C, Jamrozik K, et al. Hormonal factors and risk of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: an international population-based, case-control study. Stroke. 2001;32:606-612.

47 Gaist D, Pedersen L, Cnattingius S, et al. Parity and risk of subarachnoid hemorrhage in women: a nested case-control study based on national Swedish registries. Stroke. 2004;35:28-32.

48 Green A, Beral V, Moser K. Mortality in women in relation to their childbearing history. BMJ. 1988;297:391-395.

49 Pool JL. Treatment of intracranial aneurysms during pregnancy. JAMA. 1965;192:209-214.

50 Schwartz J. Pregnancy complicated by subarachnoid hemorrhage. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1951;62:539-547.

51 Daane TA, Tandy RW. Rupture of congenital intracranial aneurysm in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1960;15:305-314.

52 Botterell EH, Cannell DE. Subarachnoid hemorrhage and pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1956;72:844-855.

53 Giannotta SL, Daniels J, Golde SH, et al. Ruptured intracranial aneurysms during pregnancy. A report of four cases. J Reprod Med. 1986;31:139-147.

54 Stoodley MA, Macdonald RL, Weir BK. Pregnancy and intracranial aneurysms. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 1998;9:549-556.

55 Minielly R, Yuzpe AA, Drake CG. Subarachnoid hemorrhage secondary to ruptured cerebral aneurysm in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1979;53:64-70.

56 Roman H, Descargues G, Lopes M, et al. Subarachnoid hemorrhage due to cerebral aneurysmal rupture during pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2004;83:330-334.

57 Kizilkilic O, Albayram S, Adaletli I, et al. Endovascular treatment of ruptured intracranial aneurysms during pregnancy: report of three cases. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2003;268:325-328.

58 Piotin M, de Souza Filho CB, Kothimbakam R, et al. Endovascular treatment of acutely ruptured intracranial aneurysms in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1261-1262.

59 Riviello C, Ammannati F, Bordi L, et al. Pregnancy and subarachnoid hemorrhage: a case report. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2004;16:245-246.

60 Miller HJ, Hinkley CM. Berry aneurysms in pregnancy: a 10 year report. South Med J. 1970;63:279. passim

61 Amias AG. Cerebral vascular disease in pregnancy. I. Haemorrhage. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonw. 1970;77:100-120.

62 Robinson JL, Hall CJ, Sedzimir CB. Subarachnoid hemorrhage in pregnancy. J Neurosurg. 1972;36:27-33.

63 Trivedi RA, Kirkpatrick PJ. Arteriovenous malformations of the cerebral circulation that rupture in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;23:484-489.

64 Fujita K, Tsunoda H, Shigemitsu S, et al. Clinical study on the intracranial arteriovenous malformation associated with pregnancy. Nippon Sanka Fujinka Gakkai Zasshi. 1995;47:1359-1364.

65 Sadasivan B, Malik GM, Lee C, et al. Vascular malformations and pregnancy. Surg Neurol. 1990;33:305-313.

66 Hatsukari I, Nagasaka H, Tsuchiya M, et al. [The anesthetic management for elective or emergent cesarean section in patients with intracranial arteriovenous malformation]. Masui. 2000;49:33-36.

67 Salcman M. Choriocarcinoma in pregnancy. Neurosurgical Aspects of Pregnancy. 1996:147-155.

68 Buckley JD. The epidemiology of molar pregnancy and choriocarcinoma. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1984;27:153-159.

69 Vaughan HGJr, Howard RG. Intracranial hemorrhage due to metastatic chorionepithelioma. Neurology. 1962;12:771-777.

70 Kobayashi T, Kida Y, Yoshida J, et al. Brain metastasis of choriocarcinoma. Surg Neurol. 1982;17:395-403.

71 Ishizuka T, Tomoda Y, Kaseki S, et al. Intracranial metastasis of choriocarcinoma. A clinicopathologic study. Cancer. 1983;52:1896-1903.

72 Weir B, MacDonald N, Mielke B. Intracranial vascular complications of choriocarcinoma. Neurosurgery. 1978;2:138-142.

73 Seigle JM, Caputy AJ, Manz HJ, et al. Multiple oncotic intracranial aneurysms and cardiac metastasis from choriocarcinoma: case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 1987;20:39-42.

74 Giannakopoulos G, Nair S, Snider C, et al. Implications for the pathogenesis of aneurysm formation: metastatic choriocarcinoma with spontaneous splenic rupture. Case report and a review. Surg Neurol. 1992;38:236-240.

75 Momma F, Beck H, Miyamoto T, et al. Intracranial aneurysm due to metastatic choriocarcinoma. Surg Neurol. 1986;25:74-76.

76 Pullar M, Blumbergs PC, Phillips GE, et al. Neoplastic cerebral aneurysm from metastatic gestational choriocarcinoma. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1985;63:644-647.

77 Stilp TJ, Bucy PC, Brewer JI. Cure of metastatic choriocarcinoma of the brain. JAMA. 1972;221:276-279.

78 Nakahara T, Nonaka N, Kinoshita K, et al. [Subarachnoid hemorrhage and aneurysmal change of cerebral arteries due to metastases of chorioepithelioma (author’s transl).]. No Shinkei Geka. 1975;3:777-782.

79 Bakri YN, Pedersen P, Nassar M. Normal pregnancy after curative multiagent chemotherapy for choriocarcinoma with brain metastases. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1991;70:611-613.

80 Akins PT, Levy KJ, Cross AH, et al. Postpartum cerebral vasospasm treated with hypervolemic therapy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1386-1388.

81 Geraghty JJ, Hoch DB, Robert ME, et al. Fatal puerperal cerebral vasospasm and stroke in a young woman. Neurology. 1991;41:1145-1147.

82 Lin TK, Chang CN, Wai YY. Spontaneous intracerebral hematoma from occult carotid-cavernous fistula during pregnancy and puerperium. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1992;76:714-717.

83 Raskind R, Johnson N, Hance D. Carotid cavernous fistula in pregnancy. Angiology. 1977;28:671-676.

84 Toya S, Shiobara R, Izumi J, et al. Spontaneous carotid-cavernous fistula during pregnancy or in the postpartum stage. Report of two cases. J Neurosurg. 1981;54:252-256.

85 Donaldson J. Neurology of Pregnancy. 2nd ed. 1989.

86 Miyakawa I, Lee HC, Haruyama Y, et al. Occlusive disease of the internal carotid arteries with vascular collaterals (moyamoya disease) in pregnancy. Arch Gynecol. 1986;237:175-180.