9 Postoperative care and complications

Introduction

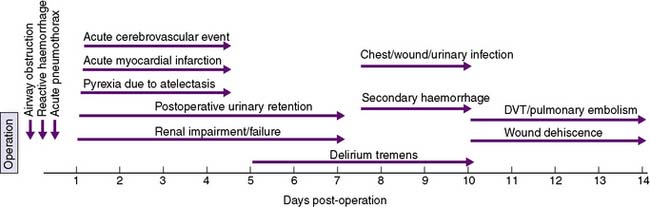

A timeline showing typical times for the development of postoperative complications is given in Figure 9.1.

Immediate postoperative care

Monitoring of airway, breathing and circulation is the main priority in the immediate postoperative period (EBM 9.1). The nature of the surgery and the patient’s premorbid medical condition will determine the intensity of postoperative monitoring required; however, the patient’s colour, pulse, blood pressure, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation and level of consciousness will be routinely observed. The nature and volume of drainage into collecting bags or wound dressings, and urinary output are also monitored, if appropriate. Continuous electrocardiogram (ECG) monitoring is undertaken and oxygenation is assessed by the use of a pulse oximeter. Monitoring of central venous pressure (CVP) may be indicated if the patient is hypotensive, has borderline cardiac or respiratory function, or requires large amounts of intravenous fluids.

Airway obstruction

The main causes of airway obstruction are as follows:

• Obstruction by the tongue may occur with a depressed level of consciousness. Loss of muscle tone causes the tongue to fall back against the posterior pharyngeal wall, and may be aggravated by masseter spasm during emergence from anaesthesia. Bleeding into the tongue or soft tissues of the mouth or pharynx may be a complicating factor after operations involving these areas.

• Obstruction by foreign bodies, such as dentures, crowns and loose teeth. Dentures must be removed before operation and precautions taken to guard against displacement of crowns or teeth.

• Laryngeal spasm can occur at light levels of unconsciousness and is aggravated by stimulation.

• Laryngeal oedema may occur in small children after traumatic attempts at intubation, or when there is infection (epiglottitis).

• Tracheal compression may follow operations in the neck, and compression by haemorrhage is a particular anxiety after thyroidectomy.

• Bronchospasm or bronchial obstruction may follow inhalation of a foreign body or the aspiration of irritant material, such as gastric contents. It may also occur as an idiosyncratic reaction to drugs and as a complication of asthma.

Attention is directed at defining and rectifying the cause of airway obstruction as a matter of extreme urgency. Airway maintenance techniques include the chin-lift or jaw-thrust manoeuvres, which lift the mandible anteriorly and displace the tongue forward (see Chapter 8). The pharynx is then sucked out, an oropharyngeal airway is inserted to maintain the airway, and supplemental oxygen is administered. If cyanosis does not improve or if stridor persists, reintubation may be necessary.

Surgical ward care

Nutrition

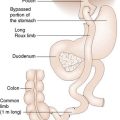

Nutrition in postoperative patients is frequently poorly managed. A few days of starvation may cause little harm, but enteral or parenteral nutrition is essential if starvation is prolonged. Enteral nutrition is preferred, as it is associated with fewer complications and is believed to augment gut barrier function. If a prolonged period of starvation is anticipated in the postoperative period, a feeding jejunostomy tube can be inserted at the time of abdominal surgery. Alternatively, a fine-bore nasogastric or nasojejunal feeding tube can be passed (see Chapter 8). If the enteral route cannot be used, total parenteral nutrition can be prescribed. Dietary intake should be monitored in all patients in the postoperative period, and oral high-calorie supplements given if appropriate.

Complications of anaesthesia and surgery

Pulmonary complications

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)

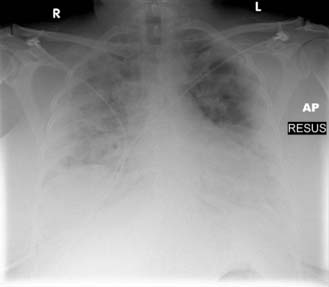

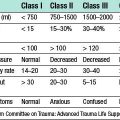

ARDS is characterized by impaired oxygenation, diffuse lung opacification on chest X-ray and an increasing ‘stiffness’ of the lungs (decreased compliance). It may result from pulmonary or systemic sepsis, following massive blood transfusion, or as a consequence of aspiration of gastric contents. The syndrome displays a wide spectrum of severity. Many minor and transient cases recover spontaneously, whereas in a proportion of cases, progressive respiratory insufficiency occurs. Tachypnoea with increasing ventilatory effort, restlessness and confusion develop. Hypoxia initially responds to an increase in the oxygen content of inspired air, but progressively increasing concentrations are required to prevent the PaO2 from falling. The pathophysiology is unclear, but endotoxin-activated leucocytes are thought to be deposited in the pulmonary capillaries, releasing oxygen-derived free radicals, cytokines and other chemical mediators. Damage to the vascular endothelium results in increased capillary permeability and leakage of fluid, causing widespread interstitial and alveolar oedema. This is seen as bilateral diffuse fluffy opacities on chest X-ray (Fig. 9.2). The lungs become increasingly stiff and difficult to ventilate.

Pleural effusion

Small pleural effusions (Fig. 9.3) are not uncommon following upper abdominal surgery, but are usually of no clinical significance. They may be secondary to other pulmonary pathology, such as collapse/consolidation, pulmonary infarction or secondary tumour deposits. The appearance of a pleural effusion 2–3 weeks after an abdominal operation may suggest the presence of a subphrenic abscess. Small effusions may be left alone to reabsorb if they do not interfere with respiration. Alternatively, pleural aspiration is performed and the fluid sent for bacteriological culture.

Cardiac complications

Urinary complications

Postoperative urinary retention

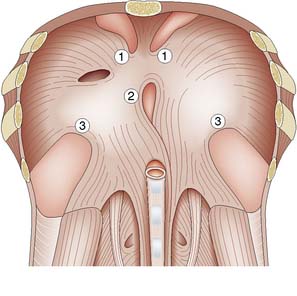

Inability to void postoperatively is common, especially after groin, pelvic or perineal operations, or operations under spinal/epidural anaesthesia (Fig. 9.4). Postoperative pain, the effects of anaesthesia and drugs, and difficulties in initiating micturition while lying or sitting in bed may all contribute. Males tend to be more commonly affected than females. When its normal capacity of approximately 500 ml is exceeded, the bladder may be unable to contract and empty itself. Frequent dribbling or the passage of small volumes of urine may indicate overflow incontinence, and examination may reveal a distended bladder. The management of acute urinary retention is catheterization of the bladder, with removal of the catheter after 2–3 days (see Chapter 8).

Cerebral complications

Venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism

These complications are discussed in detail in Chapter 21, but the essential details are summarized here for convenience.

Pulmonary embolism

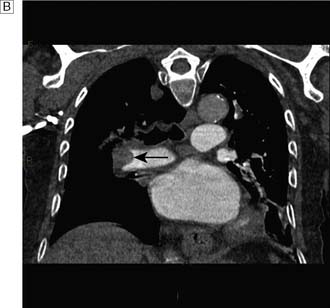

If a PE is suspected in a patient complaining of chest pain, sometimes in association with tachypnoea, haemoptysis and a pleural rub and effusion, a chest X-ray and ECG should be undertaken, mainly to rule out alternative causes of the symptoms. If these are negative, a CT pulmonary angiogram should then be performed and if this reveals lobar or segmental perfusion defects, the patient is heparinized and monitored carefully (Fig. 9.5). In such cases, it is also important to search for the source of the embolus; warfarin therapy is recommended in all patients who have sustained a pulmonary embolus, and therapy is normally continued for 6 months. If the patient cannot be anticoagulated, or sustains further PE despite anticoagulation then consideration can be given to placing an inferior vena caval (IVC) filter.

Wound complications

Infection

Infection (Fig. 9.6) is the most common complication in surgery. The incidence varies from less than 1% in clean operations to 20–30% in dirty cases. Subcutaneous haematoma is a common prelude to a wound infection, and large haematomas may require evacuation. The onset is usually within 7 days of operation. Symptoms include malaise, anorexia, and pain or discomfort at the operation site. Signs include local erythema, tenderness, swelling, cellulitis, wound discharge or frank abscess formation, as well as an elevated temperature and pulse rate. If a wound becomes infected, it may be necessary to remove one or more sutures or staples prematurely to allow the egress of infected material. The wound is then allowed to heal by secondary intention. Antibiotics are only required if there is evidence of associated cellulitis or septicaemia. If the wound infection is chronic, the presence of a suture sinus or an enterocutaneous fistula must be excluded.

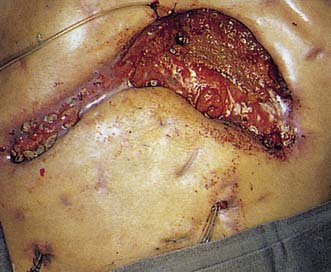

Dehiscence

The incidence of abdominal wound dehiscence should be less than 1%. Wound dehiscence (Fig. 9.7) may be partial (deep layers only) or complete (all layers, including skin). A serosanguinous discharge is characteristic of partial wound dehiscence. The extrusion of abdominal viscera through a complete abdominal wound dehiscence is known as evisceration. This rare complication usually occurs within the first 2 weeks after operation. Risk factors include obesity, smoking, respiratory disease, obstructive jaundice, nutritional deficiencies, renal failure, malignancy, diabetes and steroid therapy; however, the most important causes are poor surgical technique, persistently increased intra-abdominal pressure, and local tissue necrosis due to infection. The wound should be resutured under general anaesthesia. Incisional herniation complicates approximately 25% of cases.

Postoperative fever

Fever in a patient who has had surgery can be due to a variety of causes related to the primary disease or complications related to the surgical intervention or general anaesthesia. The common conditions that cause fever are listed in Box 9.3. The cause must be diligently identified and treated appropriately.